Vive la Paris: Why the city has such a magical effect in films

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

It’s the city of light and love – or at least that is how Paris appears to outsiders who make their movies there. From Woody Allen (Midnight in Paris), and Gene Kelly (An American in Paris) to Gary Cooper (Love in the Afternoon), and Elizabeth Taylor (The Last Time I Saw Paris) – or, even more recently, Lily Collins in the Netflix series Emily in Paris – there has been a whole sub-genre of movies and TV dramas about expats living gilded lives within sight of the Eiffel Tower.

Even the city’s rodents have a measure of style. The rats in Pixar’s Ratatouille (2007) are far more discerning and cosmopolitan than the verminous creatures found in movies elsewhere.

In Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset (2004), the novelist played by Ethan Hawke needs only to spend a few hours in Paris, walking by the Seine and having high-minded conversations about life, love, and art, to rekindle his romance with Céline (Julie Delpy), a woman he hasn’t seen in almost a decade.

In British and Hollywood movies alike, Paris has always had a magical allure for dreamers, artists, hedonists, and anyone stuck in a rut who wants to re-invent their life.

“We’ll always have Paris,” Humphrey Bogart’s Rick tells Ingrid Bergman’s Ilsa when they say farewell for the final time on the airport tarmac at the end of Casablanca (1942). Paris was where they enjoyed their fleeting moments of happiness… until the day the Germans marched into town. For them, it is a never-never land, a city of enduring romance and pleasure.

Who wants a life of never-ending drudgery in dirty, grey post-war England when France is just a short hop on a plane across the English Channel? In Paris, you can find romance, art, the best restaurants and, if you have the money, you can even buy yourself a Dior dress.

New comedy-drama Mrs Harris Goes to Paris, which is out in the UK later this year, stars Lesley Manville as a cleaning lady in late 1950s London, an “invisible woman,” who heads to the French capital in search of high couture.

“Excuse me, my dear, I’m after a frock, one of them £500 ones,” Mrs Harris tells the startled Dior representative as she unloads the wads of green pound notes she has earned by scrubbing floors.

The film is adapted from the 1958 novel by the prolific US author Paul Gallico – the former sports journalist who is best remembered today as the man behind The Poseidon Adventure and JK Rowling’s favourite kids’ book, Manxmouse.

Mrs ’Arris Goes to Paris (Gallico lopped off the “H”) is a charming but patronising tale about a working-class London “charwoman” and widow who heads to Paris on a pilgrimage to the dress shop of Christian Dior. She has been living a “drab and colourless” existence but a chance encounter with a Dior dress in the wardrobe of one of her upper-class clients completely enraptures her.

“There was no rhyme or reason for it, she would never wear such a creation, there was no place in her life for one. Her reaction was purely feminine. She saw it and she wanted it dreadfully. Something inside her yearned and reached for it as instinctively as an infant in the crib reaches at a bright object,” Gallico writes of his heroine’s sudden obsession with French high fashion.

Mrs ’Arris is far from the only downtrodden movie protagonist to experience the magnetic pull of Paris.

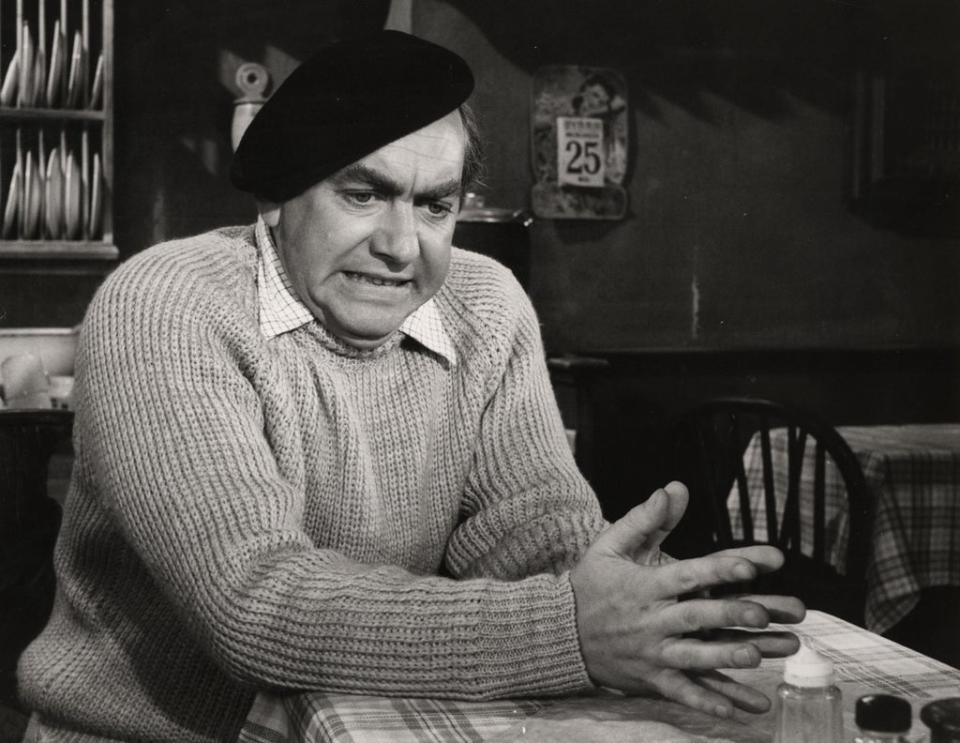

Tony Hancock’s city office worker in the British comedy The Rebel (1961) is a pettifogging British everyman – more in the Mrs Harris than the Bogart mould. He lives in a seedy south London boarding house. Like everybody else on his morning commuter train, he wears a bowler hat and carries an umbrella. Hancock, though, fancies himself an artist. As soon as he gets home at night, he pulls on his beret and smock and starts sculpting his “Aphrodite at the water hole”, a grotesque concrete nude based on “women as I see them”. The head comes from some masonry he’s stolen at the local pub; the left leg has been pinched from the local war memorial and the rest of the sculpture is made up of “chunks” taken from the railway bridge, the town hall, and the public library.

His landlady (Irene Handl) is appalled. “I’m an impressionist,” he protests. “Well, you don’t impress me,” she replies, yelling at him to get the monstrosity out of the house.

“All artists dream of Paris,” Hancock soon learns. That is where he, therefore, bases himself. He thrives among the pale-faced existentialists in their black pullovers. His paintings are appalling but have an odd, childlike quality that intrigues the critics. Soon, he moves into his abstract expressionist “action” phase, throwing paint onto the canvas, smearing it with his wellington boots, and then riding over it on his bike.

The Rebel is a knockabout satire but it has a storyline very similar to those of many much more earnest films in which artists and writers arrive on the Left Bank in search of love and inspiration.

US director Alan Rudolph’s The Moderns (1988) portrays Paris in a very idealised fashion. It is set during the mid-1920s, the period when Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and other American writers and artists from the so-called “Lost Generation” colonised the city. They wrote, painted, drank wine in cafés on the Place St-Michel, had affairs, and behaved very much like Hancock in The Rebel, although they didn’t laugh at themselves in the way he did.

On the screen, strait-laced Americans always loosen up as soon as they get to Paris. The strength of the dollar allows them to eat and drink well. Characters without any obvious talent embrace a bohemian existence. Prim midwestern puritans give in to their licentious side.

Philip Kaufman’s steamy arthouse biopic Henry & June (1990) dramatises the story of writers Anais Nin (Maria de Medeiros) and American writer Henry Miller (Fred Ward) whose lives become entangled in the Paris of the early 1930s. Nin has flings both with Miller (author of the notorious Paris-set novel Tropic of Cancer) and with his strapping wife June (Uma Thurman).

The settings in Henry & June are crucial. All those highly stylised sex scenes would have seemed out of place if the film had been set in, say, Cleveland or Boston.

The US censors gave Henry & June an NC-17 certificate – a rating generally reserved for the most extreme exploitation films. However, thanks to the upmarket Parisian locations and artistic aspirations of the protagonists, the film was still nominated for Oscars, while critics described it as an “erotic masterpiece”.

The British, meanwhile, may make more downbeat, less explicit films about Paris but being in the city still works wonders for their protagonists’ joie de vivre. Take Roger Michell’s Le Week-end (2013), in which a jaded middle-aged British couple played by Jim Broadbent and Lindsay Duncan are rejuvenated after a few days in town.

It’s striking, though, how differently the French themselves portray Paris in their own movies. Look beyond the kitsch charm of 2001’s Amélie with a gamine-like Audrey Tautou as the innocent waif adrift in Montmartre, or the romantic vision of vagrancy in Les Amants du Pont Neuf starring Juliette Binoche and Denis Lavant as the lovers living rough and you’ll find a far harsher vision of the city. Movies like Jean-Claude Brisseau’s Sound and Fury (1988) or Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) explore the brutal reality of life in housing estates in the Paris suburbs, where poverty and violence are rife.

In François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959), the city becomes an unhappy, delinquent kid’s playground.

Claire Denis’s Vendredi Soir (2002) suggests Paris is caught up in near-permanent traffic gridlock and public transport strikes.

Other French films, whether comedies or dramas, are much more matter of fact than the Hollywood and British films shot in Paris. Local directors don’t make a fuss about the city. They are too used to its landmark streets and locations to be seduced by them.

Imagine trying to reverse engineer Mrs Harris Goes to Paris by making a film about a Parisian charlady coming to London to buy a designer dress. It simply wouldn’t work. There is no tradition of French protagonists travelling to the UK in search of rain, warm beer, and red telephone kiosks. In this case, the movie traffic is one way. The signs all point to Paris.

It is debatable whether the Paris shown by Hollywood and British filmmakers has very much to do with real life in any case. Filmmakers make sure that their movies conform to their preconceived notions. Mrs Harris, then, isn’t really going to Paris at all but into a make-believe world inspired by all the other British and American movies which have already painted it in such a magical, idealised light. When it comes to wish-fulfilment fantasy destinations on screen, there has only ever been one city on the itinerary.

‘Mrs Harris Goes to Paris’ is released on 30 September