Vermont's oldest loon hit by a boat. How volunteers are working to protect the species

The eerie and melodic call of the common loon is not an invitation to get closer. Consider the call a signal that says, "I’m here, so pay attention."

Necropsy results for Vermont’s oldest loon referred to as "Newark Pond Male" reveal a human-related death and what Vermont loon experts have known from the beginning: Despite loons’ apparent conservation success, Vermonters need to stay vigilant in an effort to protect them.

Eric Hanson, lead biologist on Vermont Center for Ecostudies’ (VCE) Loon Conservation Project, banded the bird in 1998, meaning it was at least 31 years old when it died.

“The Newark Pond Male’s advanced age was a testament to the success of loon conservation efforts in Vermont," Emily Anderson and Hanson wrote in a news release from VCE. "When the loon was originally tagged by Hanson in 1998, loon populations across the Northeast were so low that the species was listed as Endangered in Vermont."

The average lifespan for a loon is between 15 and 30 years old.

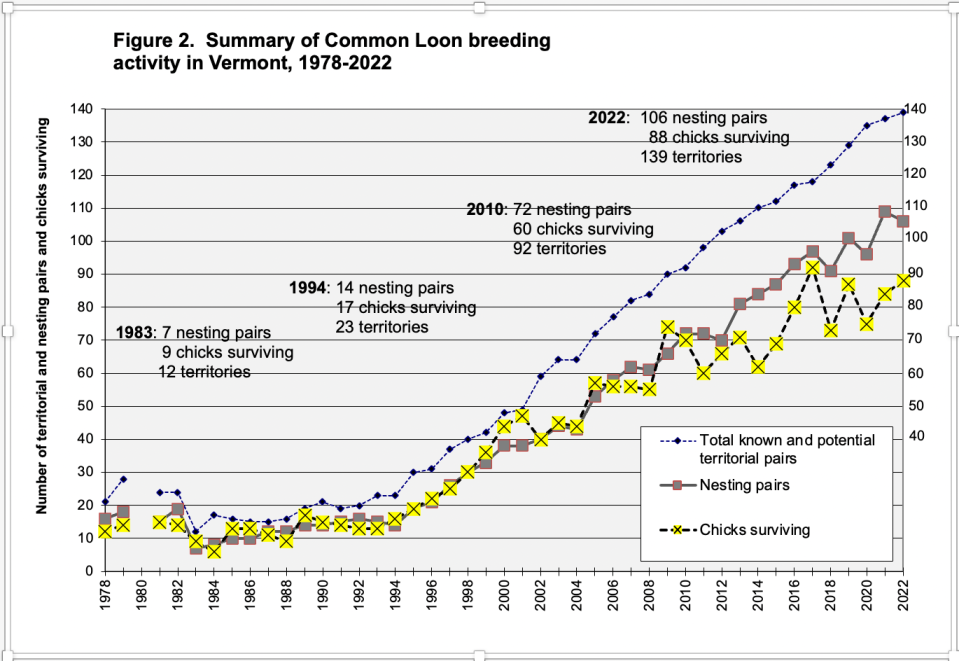

Since their removal from Vermont’s endangered species list in 2005, loon breeding pairs have increased annually, thanks to long-standing, local conservation efforts.

Burlington has a new zoning district. What it means for 13-acres of parking lots

How did Vermont's oldest living common loon die

The necropsy, conducted at Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine in Massachusetts, determined the bird died of blunt force trauma to one side, according to Anderson and Hanson.

This kind of trauma points to a likely collision with a motorboat.

The VCE loon conservationists hope the news from the necropsy can raise boaters’ awareness about their role in loon protection. A guide of precautions boaters should take can be found on VCE's website.

How humans can help prevent loons from dying

An increase in breeding loons means an invariable increase in human-loon interactions.

“I think that we are often used to sort of having things move out of our way, or moving things out of our way, in order for us to do what we want to do or what we need to do," said Rosalind Renfrew, the Wildlife Diversity program manager at Vermont Fish and Wildlife.

Renfrew, an ornithologist, co-founded the VCE in 2007, the nonprofit that houses the Vermont Loon Conservation Project led by Hanson. Renfrew and Hanson met in the 1990s, learning to band loons in Minnesota before eventually making their separate ways back to Vermont.

"The loons are a great opportunity to look at wildlife as something you make way for; sit back and let them do their thing as well,” Renfrew said.

What to know about the common loons on Vermont lakes and ponds

Loons breed annually from May through August on lakes and deep ponds, nesting on shorelines and banks so the birds can access nests from underwater − they aren’t great on land.

Signs are often placed around nesting sites to let passersby know of their presence, so they can give the nests a 50-100 foot quiet buffer.

Are there more mosquitos in Vermont? Here's what the data says about this year.

Hanson asked that boaters follow laws that require boats to slow down to below 5 miles per hour within 200 feet of shoreline. Motorboat wakes run the risk of flooding or destroying loon nests, spooking loons so they abandon their nests, or colliding with the birds – which was the apparent cause of death for Newark Pond Male.

Loons typically leave their nests 24 hours after they finish nesting, within 24 hours of their chicks hatching. Water traffic then resumes.

For shoreline owners, maintaining healthy riparian habitat by letting shoreline vegetation go wild helps promote healthy ecosystems, which impacts the quality of fish and aquatic habitats, all of which function together.

What to know about the increasing numbers of loons in Vermont

While numbers in loon breeding pairs are up, fewer chicks are surviving into August. As population increases, so does competition. Chicks likely die in territorial fights, or adults don’t nest at all because of competition.

“Population will slowly level out, and that’s a good thing,” Hanson said.

July 15 marked LoonWatch Day, an annual project carried out by volunteers who monitor the aquatic birds' activity on local bodies of water. With 106 breeding pairs already confirmed this nesting season, LoonWatch will provide knowledge of chicks hatched this season, chick survival, as well as loons other than breeding pairs.

Anglers and dump lead sinkers can poison the birds

An initial assessment of Newark Pond Male showed a sinker in his gizzard. Before the necropsy confirmed the cause of death as blunt force trauma, Hanson said he worried the bird died of lead poisoning.

Ingestion of lead sinkers was responsible for almost 30% of loon deaths prior to 2007, which was when Vermont passed a law prohibiting lead fishing tackle weighing less than a half ounce. Following the implementation of the law, a threefold decrease in loon deaths was observed, Hanson said.

However, in the past five years, there has been an uptick in loon deaths.

Eleven birds out of nearly 350 (3%) have died as a result of lead sinker ingestion in the past five years, lower than the mortality rates prior to 2007, though still substantial, Hanson reported. Larger tackles can also emit harmful lead waste.

Renfrew and Hanson advise anglers to avoid lead tackle altogether. With the staff of their respective organizations, the pair is placing boxes at boat access areas where people can dispose of their lead tackle. These collection boxes are at over 20 sites.

When were their peak loads? Vermont's heat and energy landscape over the past decade

Dam owners work to prevent flooding loon nests

“I tell people, Vermont is probably one of the most loon-aware states in North America,” Hanson said. He cites local community efforts as a critical component of Vermont’s loon conservation success.

Working with hydroelectric companies has also been a factor in loon conservation since so many of Vermont’s lakes and ponds have dams, Hanson said. Those companies can manipulate water levels to ensure water level stability through storms, in order to prevent flooding nests.

On those lakes and ponds without dams, Hanson said his program can manage flooding by building nesting rafts, which are often managed by volunteers.

Volunteers work locally in many places including Lake Dunmore, Silver Lake and Goshen Dam

“I kind of let volunteers take charge of their lake and become the local loon expert, whether it's doing the monitoring, whether it's maintaining the raft and putting up the nest warning signs," Hanson said. "Mike Korkuc is an amazing example of that."

Korkuc, a self-proclaimed “loonatic,” began volunteering for Hanson’s loon conservation project in 2007, when the first loons nested on Lake Dunmore. Since then, Korkuc has taken charge of coordinating volunteers on Addison County's Lake Dunmore, Silver Lake and Goshen Dam.

Finding local help is necessary for the Vermont Loon Conversation Project.

Korkuc recently received a report from volunteers of two chicks hatching off a raft on Silver Lake and was there when two chicks hatched on Lake Dunmore where he and other volunteers had been upgrading a nesting raft.

At 80 years old, Korkuc floats on Lake Dunmore in his pontoon boat, watching the loons and talking to boaters. He reports that people are generally receptive once informed about the loons and happy to curtail their speedy lake activities. The general attitude of people is that they want to help. But sometimes, jet skiers and speed boats roar across the lake near the loon family, and Korkuc can’t always catch their attention – his boat doesn’t go over 15 miles per hour.

Korkuc says these “beautiful” wild birds are best enjoyed “from afar.”

“If you are getting too close to loons, they will start to move away from you when they are feeling uncomfortable, Korkuc said. "And if that happens, you should not pursue them. If you just sit quietly, very often they'll relax."

Why loon conservation is necessary

As climate change is a concern in long-term lake health, the growing consciousness surrounding loon protection represents a small, individual effort one can take in caring for ecosystems in one's own backyard, Hanson said.

“It's hard to do anything as an individual on that level, except to think about what we can do for reducing our fossil fuel imprint. But that’s a big ask. We can just kind of do the little things we can and learn from them,” Hanson said.

Many Vermonters abandoned the deposits: Here's how the $11.56 million from Vermont's 'Bottle Bill' was spent

Specific “value” shouldn’t be ascribed to a species in order for it to be deemed as worth saving, said Renfrew. The loons are important simply because they are part of the ecosystem; it wouldn’t be whole without them.

“They are one species that we've managed to bring back, and that are part of the ecosystem. And we need that, we need every part we can get. With biodiversity loss, there's always the threat that we'll see a collapse of our ecosystem, and that will have all kinds of repercussions” Renfrew said.

Are the dead trees bad for the lake How large debris affects Lake Champlain for boaters, swimmers and fish

The impact of recent floods on loons is not yet known, though Hanson reports the majority of loons have already hatched – which means many nests were not at risk of flooding.

Contact loon@vtecostudies.org if you want to get involved with loon conservation in Vermont. Keep up with loons and get up-to-date data from LoonWatch day at vtecostudies.org.

Contact Kate Sadoff at ksadoff@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Burlington Free Press: Vermont loons are protected. What to know about the effort in 2023