Verboten on Vestiaire: Behind the B Corp’s Fast-Fashion Ban

Vestiaire Collective announced a ban on 30 fast-fashion brands from its luxury resale platform on Thursday.

This is the second wave of the three-pronged ban, which applies to popular notables from Zara, H&M, Urban Outfitters and Gap to Abercrombie & Fitch, American Apparel and Uniqlo. The first wave of the Burberry partner‘s ban nixed some of the industry’s most notorious names, including Shein, Topshop, Fashion Nova, Forever 21 and Missguided. The blacklist roll call now stands at 63.

More from Sourcing Journal

UConn Researcher Tackles Protein's Possibilities for Plastic

Sequoia-Backed Fast-Fashion E-tailer Urbanic Raises $150 Million

Zara, Shein Singled Out as Fast-Fashion's High-Flying Air Freight Offenders

Since fast-fashion products can hardly be considered luxury goods, the decision has little meaningful impact on the platform’s operations. A spokesperson for the certified B Corp said the nearly six dozen brands banned represented a mere fraction—5 percent—of its total catalog.

“Indeed, this will not have a big impact on our sales, but this has not been part of the consideration when we were making the decision to ban fast-fashion brands, and we would have done it even if it did represent a higher percentage,” the spokesperson told Sourcing Journal.

As of Thursday, the platform has ditched its newly outlawed brands. Consumers can no longer purchase items from the fast-fashion brands that had previously been listed on the site, and sellers can no longer upload items from those labels.

Last year’s ban didn’t deter buyers and sellers, the company noted.

“Seventy percent of our members who used to buy or sell fast fashion items came back to our platform to keep shopping for better quality items, and we expect this number to be even higher with more time,” the spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said the collective wants to encourage people to purchase more durable, long-lasting goods.

“There is no value in fast fashion, even in resale. By banning fast-fashion brands from the platform, we are reinforcing the notion of buying quality over quantity and encouraging our community to invest in craftsmanship at better prices,” the spokesperson said.

At a Thursday morning panel discussion held at Chloé’s Greene Street store in Manhattan, Samina Virk, North America CEO of Vestiaire Collective, said the company will inform affected sellers of the reason behind the removal and alternatives they can consider.

The spokesperson told Sourcing Journal those suggestions will include re-styling items to “make them feel fresh again,” upcycling, organizing clothing swaps, donating to charities in the community and using end-of-life garments to make cleaning cloths.

But if sellers now find themselves with rejected goods that they still want to offload elsewhere, they have plenty of opportunity to do so in a saturated resale market. Even though Vestiaire Collective has banned these brands, other popular, non-luxury resale platforms from Poshmark and ThredUp to Mercari and eBay overflow with low-cost fast-fashion listings.

Lauren Singer, managing partner of Overview Capital, a New York investor in climate tech solutions, also participated in the Thursday panel. She served as one of nine advisors to Vestiaire Collective as it worked to define fast fashion.

Singer said the advisors landed on five categories to help identify brands that should be banned: low price point, intense renewal rate, wide product range size, speed to market and strong promotional intensity.

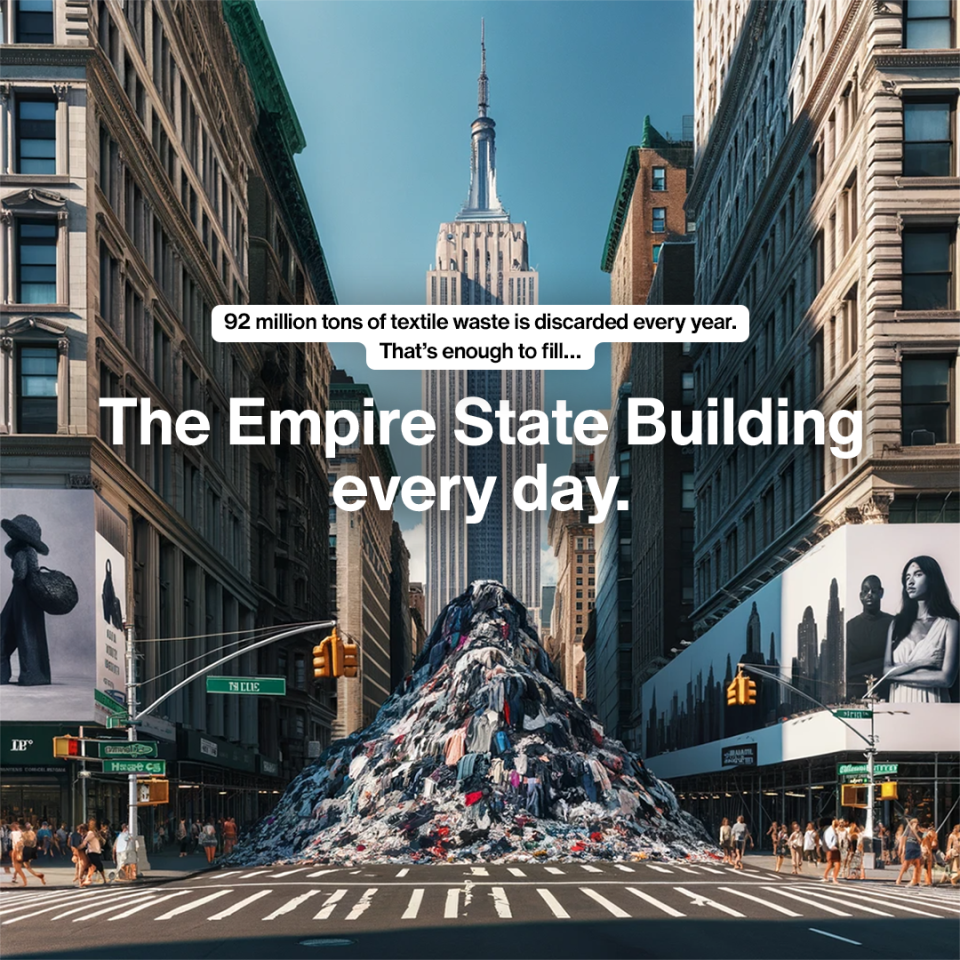

The Kering-backed unicorn has also released a side-by-side awareness campaign that shows consumers what textile waste would look like in some of the biggest and most famous American and European cities.

“The goal of our Fast Fashion Ban campaign is to use our influence as the world’s first fashion resale B Corp to transform the fashion industry and influence the rest of the fashion ecosystem—industry experts, influencers, consumers, NGOs, brands, investors, and policy makers—to put an end to fast fashion collectively,” the spokesperson said. “We want to change the overall shopping behavior of consumers for the long term and encourage them to consume more consciously.”

Singer said education will be key in helping consumers and brands alike make better decisions around overconsumption and overproduction, respectively.

She noted that the Vestiaire Collective initiative is a step toward helping clean up the mess caused by those issues.

“What [Virk] and Vestiaire are doing is really taking care of the problem at the latest stages of its life—so diverting from landfill after all of the decisions have already been made,” Singer said.

In order to get to the true root of the problem, Singer said, brands must be willing to produce garments in a way that would make them less harmful to the environment at the end of their lives. Fast fashion inherently works against that goal, she said.

While the Alexander McQueen partner positions itself at the end of the product lifecycle for the original buyer, it said it is willing to assist brands and retailers in adopting more eco-conscious practices at the earlier stages too.

“Our door is open to work hand in hand with fast-fashion brands if they need advice on how to improve their production and marketing processes. This is not a journey we can embark on alone, we need other players of the industry to join our movement so collectively, we can change the fashion industry for a more sustainable future,” the spokesperson said.