Vampire virus? Scientists may have discovered the first one

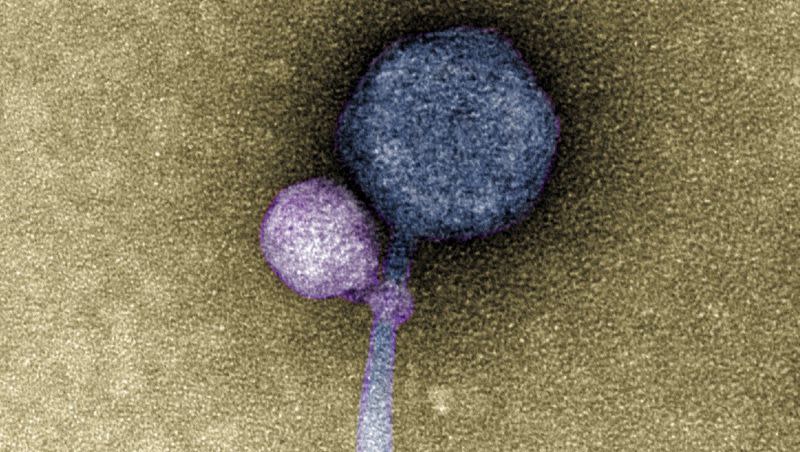

In a scene reminiscent of Dracula, researchers at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County looked into a microscope recently and found something never documented before: a virus latched onto the neck of a different virus.

In a news release, the research team said it’s well known that so-called satellite viruses depend on their host organism and a “helper” virus to replicate inside cells. And the two are expected to be in close proximity for a short time. “But there are no known cases of a satellite actually attaching itself to a helper — until now,” the release said.

In a paper published in the Journal of the International Society of Microbial Ecology and jointly written by colleagues at Washington University, the researchers describe the actions of the satellite bacteriophage, which is science speak for a virus that infects bacteria cells. The satellite virus consistently latched onto the neck of the helper bacteriophage.

The Washington Post reports bacteriophages “also called simply phages, are among the most abundant organisms on Earth. There can be millions in a gram of dirt.”

Images taken by Tagide deCarvalho, assistant director of the Baltimore University’s College of Natural and Mathematic Sciences and the paper’s first author, show that 80% of the helpers had a satellite on their necks. And some of those that didn’t have tendrils left from satellite viruses at their necks, described by senior author Ivan Erill, professor of biological sciences, as “bite marks.”

The researchers explained that most of the satellite viruses have a gene that lets them integrate with a cell’s genetic material once they’ve entered the cell, allowing the satellite virus to reproduce whenever a helper cell enters after that. The host cell copies the satellite’s DNA and its own as it divides.

Per The Washington Post, the scientists theorize that the “small virus, called MiniFlayer, lost the ability to make copies of itself inside cells, which is how viruses reproduce. So evolution devised a clever, parasitic workaround. MiniFlayer takes advantage of another virus, dubbed MindFlayer, by grabbing onto its neck, and when they enter cells together, MiniFlayer utilizes its companion’s genetic machinery to proliferate.”

The researchers assume it has no gene that allows it to integrate with the host cell, so it instead stays close to the helper.

“Attaching now makes total sense,” Erill said in the prepared statement. “Because otherwise, how are you going to guarantee that you are going to enter into the cell at the same time?”

He told the Post that “viruses will do anything. They are the most creative force of nature. If anything is possible, they will come up with a way to do it. But no one had anticipated that they would do something like this.”

The discovery of the vampire virus was a fluke. The Baltimore research team was isolating bacteriophages from environmental samples and sending them out for sequencing. The lab at the University of Pittsburgh sent back the sample containing MiniFlayer, noting it was contaminated. So the researchers tried again, with the same result.

That’s when they pulled in deCarvalho, who has access to a transmission electron microscope.

The team's discovery sets the stage for future work to figure out how the satellite attaches, how common this phenomenon is and much more. “It’s possible that a lot of bacteriophages that people thought were contaminated were actually these satellite-helper systems,” Carvalho said. “So now, with this paper, people might be able to recognize more of these systems.”