How Valerie Steele Went From a Modern European History Ph.D Candidate to Director and Chief Curator of The Museum at FIT

The curator reflects on more than two decades at the helm of the museum and how a story about the Victorian corset changed her entire career path.

In our long-running series, "How I'm Making It," we talk to people making a living in the fashion and beauty industries about how they broke in and found success.

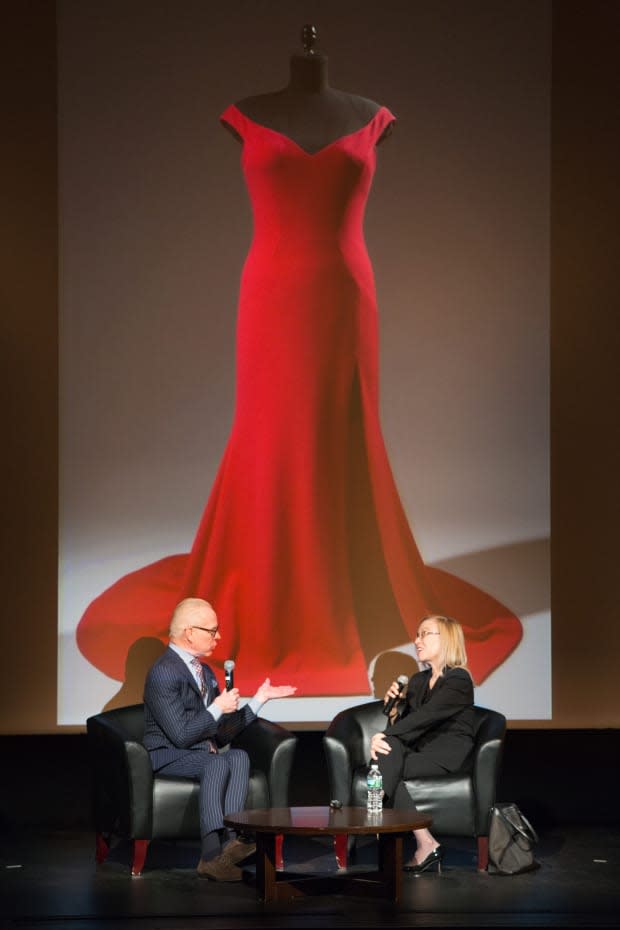

This year The Museum at FIT celebrates 50 years as an accomplished, groundbreaking museum for the fashion industry and its admirers. While an undeniable feat that comes from the hard work of many, there's one person who can be credited for truly making the museum what it is today: Dr. Valerie Steele.

As director and chief curator of the museum since 1997, Steele has produced over two dozen boundary-pushing, breathtaking exhibits that have all but banished the notion that studying the history of fashion is "frivolous." It was a path she, herself, hadn't considered until grad school. "My classmate gave a presentation on two articles from the feminist journal, Signs, and they were about the Victorian corset. Was it oppressive to women or was it sexually liberating? It was just like a lightbulb went on: fashion's part of culture, I can do fashion history," Dr. Steele tells Fashionista.

Related Articles

How Museums and Cultural Institutions Have Shaped the History of Body Diversity

The Special, Behind-the-Scenes Ways Museums Bring Costume Design Exhibits to Life

Why Black Fashion Designers Needed Their Own Museum Exhibit

Curating a college-owned museum comes with plenty of pushback from critics that it's not a "real" museum. But Steele has proven time and time again, alongside her trusted team, that the museum creates something special and far beyond what free-standing museums are producing about fashion. It's not uncommon to see larger museums reproduce similar exhibits to ones The Museum at FIT has already put on — something Steele actually encourages.

As a fashion historian and author — she has written about 25 books and founded the first scholarly magazine on fashion studies, Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture — Steele is an undeniable force in preserving and celebrating fashion for what it is: a beautiful and societally responsive form of expression.

Ahead of The Museum at FIT's upcoming exhibit "Paris, Capital of Fashion," curated by Steele and inspired by her time studying fashion in Paris, we spoke with her about breaking into the fashion industry, how fashion curation has evolved and career advice for future curators.

What are your earliest memories of being interested in fashion?

I don't know if I remember this or it's just because I remember seeing the picture. But when I was about five years old, I remember dressing up in an evening dress my mother had and holding a fan and posing for the camera. It probably came when I was a teenager, really, though I remember as a child wanting to be an actress, which definitely involved the idea of dressing up, so I think that was there.

What were your first steps entering the fashion industry?

My first discovery that I could work in fashion came the first term in graduate school. I'd gone to Yale to get a Ph.D in Modern European Cultural and Intellectual History. Everybody had to give a report on two articles in a scholarly journal, and I don't even remember which ones I read — they were probably about the French Revolution. But my classmate gave a presentation on two articles from the feminist journal, Signs, and they were about the Victorian corset. Was it oppressive to women or was it sexually liberating? It was just like a lightbulb went on: fashion's part of culture, I can do fashion history.

So from that point on, that's all I did in graduate school. I wrote my doctoral dissertation on it ('The Erotic Aspects of Victorian Fashion'), and got a post-doc at the Smithsonian in the costume collection. Then I turned my dissertation into my first book and, of course, was completely unemployable at any normal history department. I got an adjunct job at FIT and other adjunct jobs like at Parsons and Columbia and NYU — places where they were teaching fashion.

Did you have any mentors when you were starting out?

My Ph.D advisor didn't mind that I was working on fashion because he was a big Freudian, and fashion obviously has to do with the body and sexuality. So he didn't object to it. I had another couple of professors who I would go over to at the art history department. [One professor] was very important for me because he did the material culture, so you learned how to analyze objects and that got me into museum collections to look at actual dresses and to measure corsets. That was super important because most historians just read, they don't look at objects.

One of them was also Richard Martin, who was the director of The Museum at FIT back in the '80s and early '90s. He did great shows, like in 1987, "Fashion in Surrealism" or 'Three Women.' The 'Three Women' inspired me to research and write my third book, Women of Fashion, the history of designers in the 20th century. I was so intrigued by him questioning, is there something different that women designers bring?

What do you think is your greatest achievement so far?

I've written about 25 books and I've done more than two dozen exhibitions and I helped make The Museum at FIT into a real fashion center. But possibly some people would say that maybe the biggest contribution was that I founded the first scholarly magazine on fashion studies, which is called Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture. That also really helped establish fashion studies as a legitimate, intellectual field. The first issue of the magazine came out in 1997, which is exactly when I first was hired as the Chief Curator at The Museum at FIT. That was a super great year for me.

Why do you think there is that idea that fashion can't be studied in the same way that so much other history can be?

For a long time, the idea was that fashion was too frivolous a topic. Academics — quite apart from being what I've called the worst dressed, middle-class occupational group in America — there's a really strong prejudice in academia against things that are material instead of intellectual. Fashion was kind of despised as being feminine and superficial, and bourgeois, conformist and anti-feminist. There were a lot of reasons why scholars didn't take fashion seriously. In general, the feminist movement, too, felt that fashion was oppressive and unworthy. But then I think because of the LGBTQ movement, there was a lot more interest in fashion as being a kind of self-expression, and even a sort of political statement. Then you started edging into the idea that fashion might be legitimate as a cultural study. I think that was an important moment.

Then the material turn also; the fact that I was looking at objects in museum collections. That was important because museum audiences realized, I think before academics did, that fashion was interesting and they liked to see fashion exhibitions. Even though most of those exhibitions, for a long time, were very lightweight, like, here's some pretty dresses in chronological order, it still offered possibility to do exciting shows. I think the best exhibitions and the best books are the ones that are thought-provoking, that get you thinking and asking more questions and digging deeper.

What are the benefits and challenges of curating a college-owned museum?

On the problematic side, a lot of people say that you're not a 'real' museum because you're not an independent, free-standing museum, which is super frustrating. Or they're confused and think you're only showing student work then. But the plus side is that universities and colleges understand that exhibitions and books are about producing and disseminating knowledge, so they're not scared of having you do a smart show, even if it's controversial, like when I did a 'Queer History of Fashion: From The Closet to the Catwalk.' I was so pleased because an FIT student wrote in the sign-in book, 'I'm so proud that my school did this show before anybody else did a show about this.' It's true that maybe a city or a national museum might be afraid to do a show that's about LGBTQ people, but a school goes, well that's a legitimate topic.

How has your creative process evolved over the years that you've been working?

When you do a book you're really working alone. You're there in the library doing research or interviewing people. But when you do an exhibition, it's like making a film — it's really a team effort. I've had so much and learned so much working with all my colleagues at The Museum at FIT and colleagues at other museums. That's one thing I'm really proud of, putting together a super great team at The Museum at FIT with lots of creative people who have brilliant ideas that would never occur to me. We all work together, like people working on a film, to make each show special.

What do you look for when you're hiring new people for your team?

I'm looking for people who are intelligent and creative. I think those are the two most important things. Also, somebody who is able to work with other people because there are people who are intelligent and creative but they're just so difficult, they're neurotic — they can't function with other people. Those are the three things that I'm most looking for. Anything else they can fill in, they can find out more later. They need to have a basic knowledge of what their job is going to do, but they can still learn from there. I also like people who are self-directed — who know what they want to do and can figure out how to do research and think clearly about it.

What advice would you give anyone looking to enter the field of fashion curation?

Try and picture exactly what you want to be doing and then figure out how would you get there. If you want to do fashion curation, what are the graduate programs you can take? What are the internships you can take? Are there graduate programs where you can be working with a museum as an intern at the same time? Try to put together imaginary or virtual shows yourself. You can put shows together online. Before Judith Clark started to be hired by museums to do exhibitions, she rented a tiny little room in London and just mounted her own exhibitions. They could have like three to seven dresses that she borrowed from friends, but they were so smart and interesting that people sat up and paid attention. You may not be able to do a full exhibition all by yourself but you can do a book with a good idea for an exhibition, you can do a virtual exhibition, you can write articles and reviews of other exhibitions. You can figure out how to get your ideas out in the world.

How has social media impacted the way you design exhibitions now?

We try and create Instagram moments because people definitely like taking pictures. I had to gently coax our museum head of conservation into allowing people into taking pictures because, historically, you were not allowed to take pictures in a museum. Some museums are still like that but I'm always shocked when the guards run up and say, 'You can't take a picture.' Nowadays it's free advertising, so we try to get moments that are beautiful shots and sight lines so that people can take good pictures and sometimes we just create a particular look that they can pose in front of. That's important.

Is there anything else that you think has been integral to your continued success?

It sounds boring but you have to work really hard. That's part of what being self-directed is about. I think that you have to really, really love what you do and really work hard at it. Things get easier but there's still a lot of work involved in whatever kind of research and writing and putting on exhibitions you do. I think I would try to get across to people that it's really not enough to just have a kind of pretty or amusing exhibition. You really want to do something that's original, that advances the whole field of fashion studies. So, it's not just one more show that says the same old thing.

Like one of my young curators, Colleen Hill, came to me with a project about doing a show on fairytale fashion. She had done all this research on fairytales and figured out when designers were being inspired by Red Riding Hood or glass slippers and what all these fairytales could possibly mean to us and our culture. And that was really a thrilling show, that never would have occurred to me, but once she told me I thought, that's perfect. That's totally brilliant.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sign up for our daily newsletter and get the latest industry news in your inbox every day.