The Unsolved Mystery of the Malibu Creek Murder

Part One: Before

On June 22, 2018, at 4:44 a.m., in a campground below the Santa Monica Mountains, a man asleep in a tent he’s sharing with his two young daughters is shot. Most of the other guests at the Malibu Creek State Park campsite don’t wake up; those that do later report hearing three to four loud bangs, which they don’t reliably identify at first as gunshots. They by and large go back to sleep and wake up only when deputies of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department unzip the doors of their tents, some hours later, to ask precisely when and how they arrived, and whether they have any weapons with them. The father in the tent is pronounced dead at the scene.

One camper, a youth pastor, gathers his wife and several young-adult charges and joins the exodus of others trying to leave the campground. He ends up in a traffic jam, his car next to what has become a crime scene, and so he spends 20 long minutes looking over the top of his steering wheel at the two little chairs that remain upright outside the victim’s tent. The victim’s daughters, who are unharmed, are collected by the victim’s wife’s brother-in-law, who was camping at an adjacent site with his own two young children, and taken to the Malibu/Lost Hills Sheriff’s Station. The man in the tent’s wife arrives at the station several hours later to claim her daughters. “There is no additional information available at this time,” reads the press release from the LASD issued that afternoon.

Not long after, LASD homicide detectives issue a second release, adding that they are “aware” that there have been “other shootings near the location in the past, however, there is no evidence that suggests this incident is related to any prior shootings near the location.” Nevertheless, stories begin to trickle out: A man trained as a wildlife biologist was camping in the area in early November 2016 when he was awoken in his hammock by a stinging pain in his right arm. He thought he’d been bitten by a rodent or a bat, perhaps, while he slept. The hospital gave him a shot for rabies and sent him home. It was only as his arm began to heal that he noticed that metal pellets, similar to bird shot, were trickling out of the wound.

Another woman reported that one night in early January 2017, she and her partner had parked their car at Malibu Creek State Park and were sleeping in the vehicle when they heard a loud bang and an echo of burning metal—like a dream. They treated it as such. But when they awoke in the morning, they found a sizable hole in the back of the car and then, wedged down by the spare tire, what appeared to be a shotgun slug.

So maybe there was a dangerous man with a gun on the loose? That’s what some residents in the area begin to theorize. People who had lived in Malibu for a while remember that this isn’t the first time something terrible and inexplicable has happened out in the remote hills that loom beside their city. In 2009 a 24-year-old woman named Mitrice Richardson went missing after being detained—for acting erratically at a restaurant and possessing marijuana—and then released by deputies of the same Malibu/Lost Hills Sheriff’s Station that had briefly sheltered the man in the tent’s daughters. Eleven months later, Richardson’s remains were found within a few miles of the station. In 2017 another woman, 20-year-old Elaine Park, was last seen in Calabasas before vanishing as well; a few days later, her car was found on the Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu, abandoned, with all her possessions inside. A month before the death of the man in the tent, a mutilated body was discovered across the street from Malibu Creek State Park, followed by a second body in July, also showing signs of violence. The area, homicide investigators say, was known to be a dumping ground for bodies—gang-related killings, mostly, with no other connection to the region.

There is something so incongruent about violence striking an area this beautiful and celebrity-filled that many of these stories don’t make it beyond the local papers. But the incidents, nevertheless, persist. Four days prior to the death of the man in the tent, a man driving his Tesla at about 4:30 a.m. down Malibu Canyon Road reports being shot at. By July, residents of the area are regularly reporting hearing gunshots echoing through the hills and advising one another to lock their windows and doors. One couple, living in a particularly remote house in the hills above the ocean, arm themselves with two shotguns for the purpose of home protection; they join their neighbors at the local gun range one weekend, practicing for what may yet come. Maybe the man in the tent was a one-off thing. But the alternative—that the killing was simply random—is worse, residents of the area begin to understand. Could you just die from being in the wrong place at the wrong time? You could, couldn’t you? People in Malibu liked to think sudden, violent death was something that happened elsewhere. But maybe that wasn’t true.

The LASD has no leads that they are willing to disclose to the public. They hold a community meeting in August but tell anxious residents that they can’t really tell them anything—if the earlier shootings are connected to the death of the man in the tent, the LASD has found no evidence of the fact, according to James Royal, one of the lieutenants leading the meeting. In the void, people craft theories of their own. The man in the tent had been a scientist at a pharmaceutical company; had he been targeted for assassination due to something valuable he was working on? Did the killing somehow relate to the marijuana grow farms that Mexican cartels were said to cultivate up in the remote reaches of the park? Were the disappearances of Richardson, Park, and others somehow linked to this new crime? In August another person, a 21-year-old man, goes missing in the area. Months later, the key to his BMW is found, discarded on a trail. Residents mutter about something malevolent and beyond comprehension going on in the mountains that divide the ocean from the Valley.

As for the wife of the man in the tent, she releases a statement: “I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my family, friends, and the community at large for the outpouring of love and support over the loss of someone who was beloved to so many.” A reward is offered, with funds drawn from the city of Malibu, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, and the dead man’s pharmaceutical company, in the amount of $30,000. The man’s family then recedes from public view.

The wife of the man in the tent spends the fall grieving and trying her best not to read the news, because the news is full of speculation about what may have happened to her husband, and that is not a road she feels able to walk down. On the internet, there are outlandish theories about the death of the man in the tent: Why he was killed? Who may have done it? Like everyone else, she wonders who did it. But mostly she feels like none of the speculation has anything real to do with her or her husband, a man she’d known and depended on for just about half her life. She just misses him.

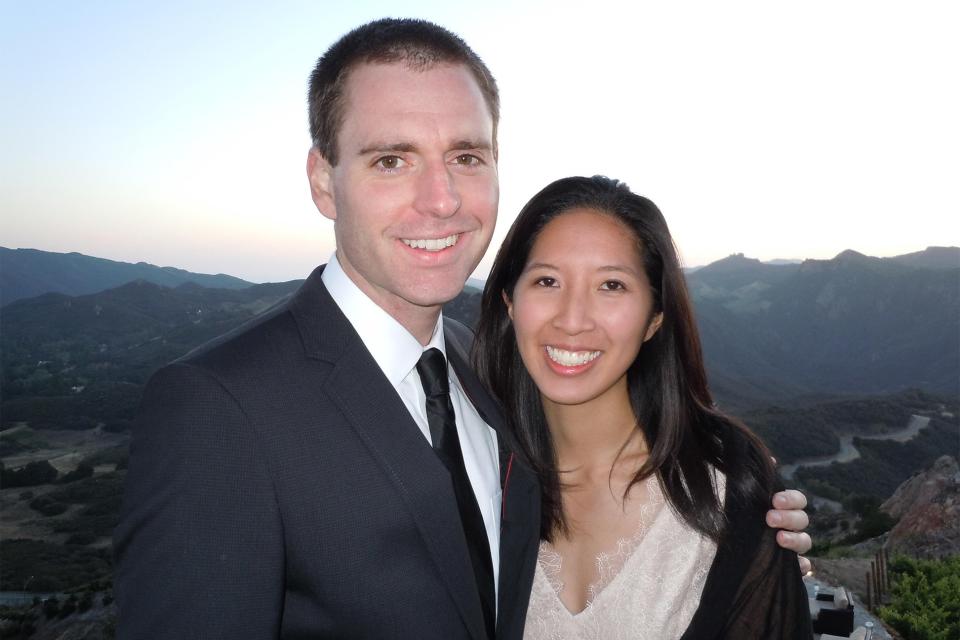

Her name is Erica Wu. His was Tristan Beaudette. They met a long time ago, in high school. Erica, who has long loose hair and high cheekbones and a thoughtful face, is the fourth-youngest of five sisters; her father passed away when she was eight years old. She grew up anxious, a planner, keen to control what there was to control. When she met Tristan, he seemed like the opposite of everything she was. He didn’t overthink things or worry too much. He was just…solid. Like Erica, he’d grown up in Fresno, California, descended on both sides from longtime residents of the area. His father sold insurance. His mother was a substitute teacher and, later, a wildlife educator. Like Erica’s, his family had fractured during childhood; his parents split up when he was just three—young, but still old enough to remember.

Tristan and Erica went to different schools but met their senior year, when Tristan needed a date to his winter formal. They were introduced through a mutual friend. The year before, Tristan had grown four or five inches; when he and Erica met, he was still getting used to his weird new body. But, Erica noticed, he wasn’t self-conscious. About anything, really. He was the type of guy who liked what he liked uncomplicatedly. He loved nature and chemistry and Ultimate Frisbee. For his senior class picture, he forewent the usual dress shirt and wore, without embarrassment, a full tuxedo.

It was January when Tristan took Erica to the winter formal. (He wore the tux again.) At the end of the night, when they said goodbye, Erica wondered if she was ever going to see him again. She already knew she was leaving, to go to school at Stanford; Tristan was going to study abroad for a year in Switzerland. It wasn’t the best time to start a relationship. But Erica liked him. Probably even loved him already. Not long after the winter formal, they went on their first proper date. Tristan picked Erica up and took her to dinner. They were kids, with no real sense of what was going to come next, except that they were both going to leave Fresno for good.

Officials close the park where Tristan died. “Our hearts go out to the victim and his family during this difficult time,” State Parks officials say in a statement. “The safety of park visitors is our top priority.”

There is reason to suspect the area is still very dangerous. Local news outlets report that sheriff's deputies have responded nine different times to claims of gunfire in the area. In September several Caltrans employees who are working on Calabasas Road, a few miles from the campground, discover the skeletal remains of what the coroner ultimately determines was a man; investigators can make out no further identification. One journalist in Malibu, Cece Woods, begins writing on her website The Local Malibu, accusing the LASD of orchestrating a cover-up related to the rash of shootings in the area in order to protect its reputation. “The city of Malibu never put out a public safety announcement, and I believe it's because they don't want to make the sheriffs look bad,” Woods tells the Hollywood Reporter. In the fall, in an unusually close runoff, the incumbent sheriff is defeated in an election that turns partially on the department’s handling of the case.

Meanwhile, there is someone, or multiple people, in the hills around Malibu Creek State Park, breaking into unoccupied buildings, stealing food and other supplies. In late July, the Agoura Hills/Calabasas Community Center is burglarized; in September, it’s a commercial building owned by the Las Virgenes Municipal Water District. In October, Spectrum Development, an engineering consultancy, reports a third break-in: Surveillance footage from the site shows a man stealing food while carrying a rifle and wearing what sheriff’s deputies call “tactical gear.” The next day, residents report an ominous massing of SWAT vehicles, patrol cars, and other tactical units near the Spectrum Development offices. The manhunt, which begins at rush hour, lasts through most of the day, but the suspect is not found. That night, residents report again hearing gunfire.

Two days later, the Water District building reports a second break-in on its property; two days after that, a maintenance worker is driving through a park about a mile south of the Malibu Creek State Park campground when he meets a man who asks him for a ride out of the canyon. The park worker, noting the man’s resemblance to the suspect in the prior burglaries, refuses; instead he drives off and calls the sheriff’s department, prompting the second massive manhunt in the area in one week. Three helicopters hover over the park for most of the day, before darkness falls and the manhunt is called off.

Then the Agoura Hills/Calabasas Community Center is broken into for the second time: The burglar shatters a glass window early in the morning and vandalizes a vending machine inside, presumably in search of food. Deputies return to the area, but this time, after noticing fresh boot prints during their search, they track their suspect to a ravine north of Mulholland Highway and west of Las Virgenes Road, and finally arrest a 42-year-old man named Anthony Rauda, who is reportedly dressed in all black and carrying a rifle when he is apprehended. Law enforcement sources tell the media that their suspect is a “survivalist,” who often slept outside, breaking into various places in search of food. A family member of Rauda’s tells a local ABC News affiliate this is in fact the second time he’d been arrested in the past four months; on the first occasion he’d been apprehended for trespassing but was released. The suspect’s family member said he’d been living in the area for the past ten years and was afraid of people.

Residents speculate that perhaps this was Tristan’s killer. But when Rauda appears in court in November, it is for a probation hearing to address alleged violations of his parole; he’s removed from the courtroom after he begins shouting profanity and pounding on his holding cell. As bailiffs drag him out, he attempts to fire his court-appointed attorney.

Could Rauda have been disturbed enough to have been taking random shots at people up in the hills these past few years? There certainly seemed to be evidence to suggest it. But if Rauda was the shooter, then nearly every theory spectators have been nurturing about the crime and the killer’s possible motives would be rendered false. It would mean that all that chaos, paranoia, and terror added up to just this guy, one haunted guy, who was afraid of people. Also if the police really had a ballistics match, wouldn’t they have charged him with murder then and there? And what about all the gunshots that people continued to hear at night, even after the suspect was arrested?

One week later, a fire breaks out in Woolsey Canyon, on the property of an industrial research complex owned by Boeing. Santa Ana winds push the fire south; the whole area, including the Malibu Creek State Park campground, burns for nearly two weeks, destroying hundreds of homes and who knows what else, turning the hillsides black.

After high school, Erica went to Stanford and, after he returned from Switzerland, Tristan went to U.C. San Diego. But they kept up a correspondence, e-mailing every day, speaking on the phone every night. They didn’t see each other as often as they would’ve liked. But they were finding a way to stay together.

Over the phone, Tristan would tell Erica about his Ultimate Frisbee team, the Air Squids, and how his teammates called him Morris, after Zack Morris from Saved by the Bell, because he was so clean-cut. As they approached graduation, both of them applied to graduate school: Erica got into the medical-school program at U.C. San Francisco, where she would study to become an ob-gyn. Tristan, who had his pick of chemistry labs, chose Berkeley. In June, Erica came down from San Francisco to attend Tristan’s college graduation in San Diego, on a huge outdoor field on a hot day. It took hours—hundreds of names were read off, and one by one students would come up to collect their diplomas. Erica was ready for it to end, but at the very end of a long ceremony, the school handed out an award for the highest GPA in the entire college. The award went to Tristan. He hadn’t told her about it in advance. Later, at his memorial, she’d recount this story—it showed something fundamental about him, she thought, that peculiar mix of modesty, accomplishment, quiet pride.

At first, during graduate school, Erica lived in San Francisco, and Tristan lived in Berkeley. He would bike to the BART, go see Erica, bike back. At U.C. Berkeley, Tristan had joined professor Jean M.J. Fréchet’s lab, studying polymer chemistry. He fell in with a tight-knit group of fellow grad students, who were surprised that this tall, mellow surfer-looking guy had the same aptitude for the work that they did. He liked to start sentences this way: Dude. But the work in the lab was cutting-edge—targeted application of pharmaceuticals, using polymers, to help treat various cancers—and Tristan took to it with enthusiasm. In retrospect, this was maybe the happiest Erica ever saw him.

During Erica’s second year of medical school, they got engaged. Eventually she and Tristan got a place together, in San Francisco. Their life was rounding into what they’d pictured: They were in the same place, headed toward what they hoped was the same future. In 2008, on Labor Day weekend, they got married in Tilden Park, in the hills above Berkeley, with all their friends and family present, in a big rented room with glass walls and a stone clearing outside.

At the end of December 2018, Erica Wu files a claim against the LASD, the California State Parks and Recreation Commission, the California State Park Police, and the California Department of Parks and Recreation, alleging that the agencies were aware of multiple unsolved shootings in the area where Tristan was killed but failed to appropriately alert the public. Her claim seeks $90 million in damages from Los Angeles County and the state of California. The sheriff’s department acknowledges the claim but declines to comment due to “pending litigation.”

In the first week of January 2019, authorities charge Anthony Rauda with nearly every shooting that occurred in the area over the past three years, including that of Tristan: ten counts of attempted murder, five counts of second-degree burglary, one count of murder. Officials seem to intimate the suspect is guilty of other crimes they cannot prove going all the way back to 2010. “It's a ten-year crime spree that could make a Hollywood movie,” one detective says. At the arraignment, the suspect is restrained in a chair and says very little. He does not yet enter a plea. His bail is set at $1.1 million.

Cece Woods, the local journalist in Malibu who has been skeptical since the beginning, continues to doubt the state’s case. “I personally think the shooter is still out there,” she says. There’s something about the prosecution of the burglary suspect, she says, that feels convenient—a result, perhaps, of the political fallout that followed Tristan’s death.

At the next court date in Van Nuys, a judge waits with increasing impatience for Rauda to be brought into the courtroom. Rauda is apparently uncooperative. In the courtroom is a mixture of local media members and curious spectators from the community; one of them, a young man with a safari hat, says he used to camp in that area all the time. “Nobody told me anything,” he says. He, too, thinks what’s happening now with the accused is a little fishy. “Maybe they’re making him a scapegoat,” he says.

An older man with tinted glasses and close-cropped white hair, “a man with too much time on his hands,” as he introduces himself to others in the court gallery, declares confusingly that he has it on good authority that the accused never even entered the tent of the man who died. The suspect, he says, “was just crazy, shooting people.” He thought it was suspicious that Rauda had been apprehended so close to the original crime scene: “If he knew he killed someone, why didn’t he get rid of the rifle and go to a different campground?” And some residents reported hearing gunshots long after the suspect was captured, right?

Finally, the judge announces that Rauda is about to arrive. But he never appears in the small window of the cell in the courtroom: He’s either not there or hidden, in a corner invisible to the court’s gallery. Rauda, via his public defender, pleads not guilty. The judge sets bail at $10 million. The spectators in the courtroom slowly disperse.

In 2009, Tristan and Erica moved to Southern California—to Long Beach and then Irvine—where Erica had found a residency at U.C. Irvine and Tristan found a job at a pharmaceutical company called Allergan. It took both of them time to adapt to Orange County, where everything was a drive away from everything else. But they were happy there. Erica would sometimes work 24-hour shifts as part of her residency; she’d come home, sleep through most of the day, and wake up to Tristan cooking dinner. The noise from the kitchen while she was still in bed would make her feel safe and taken care of.

They always knew they wanted kids; the question was merely how many. Tristan wanted two. Erica wanted four. So maybe, someday, they would have had three. Their first, a daughter, was born in 2014. Their second, also a daughter, was born two years later. Being a parent made Tristan happy. Tristan became a morning person, waking up with the girls while Erica caught up on sleep. He took them camping and on bike trips. He had the caretaker gene: For major holidays, Erica’s big family would meet up in San Diego, where her sister Priscilla lived, and Tristan would cook for the whole extended clan—“large-format meat,” was the family joke.

Once a year, Tristan and his grad-school friends, most of whom had remained in the Bay Area, would go away on hiking trips: Mount Shasta; the Lost Coast; Washington’s Olympic National Park; the Three Sisters, in Oregon. They’d bring alcohol and more food than they needed and spend the whole day walking or climbing. At night they’d talk about their kids, or their futures, which for Tristan seemed increasingly to mean a return to the Bay Area. Erica was coming to the end of her fellowship, and they were thinking that if they could, they’d move back up to San Francisco, where Erica had a lot of family and they both still had friends. It had been a lot of years of Erica leaning on Tristan as she moved toward her professional degree. But they were finally on the cusp of him being able to do whatever he wanted to do.

In the last year of her residency, Erica found a job in the Bay Area. She and Tristan began making plans for a move back north. They located a house, in a suburb south of San Francisco, on which they put down a deposit, and schools nearby for the girls. Tristan found a new job at a pharmaceutical company in the area. They set a date for the move, at the end of June, one week after Erica was scheduled to take a qualifying board exam. The girls were out of school, and so Tristan, with Erica’s brother-in-law Scott, offered to take their daughters out of the house the night before, so that she could study.

Years ago, before they had kids, Tristan and Scott had taken a mountain-bike trip to Malibu Creek State Park. Scott was living in Brentwood at the time, and so Tristan drove up to meet him. And then in the morning, while it was still dark, they went up to Malibu Creek State Park and started riding: through the old set of M*A*S*H, which is still there, and then up the Bulldog Trail, a steep path through wildflowers, to Castro Peak. When they finally got to the top, they rode along the ridge of the Santa Monica Mountains, and on one side was the Valley, spread out below, and on the other was the ocean, and they were up there with the whole view to themselves. And then came a small group of bikers in the other direction. Tristan and Scott got off the trail, to let them pass. Leading the pack was a guy on a mountain bike with a trailer attached, and two kids in the back, and he just bombed down the hill they’d come up, the kids screaming in joy as they descended. Tristan and Scott looked at each other like, That was fucking awesome.

After they both became fathers themselves, Tristan and Scott would always talk about returning. And now Tristan was about to move back up to the Bay Area. This was an opportunity, before he left—to go do something they loved, and show the kids a place that meant something to both of them.

On Thursday, June 21, Tristan had breakfast with Erica and their girls, and then packed up his car. At the door of their garage, he hugged and kissed Erica, wished her luck on her test, and promised to celebrate with her when they returned the next day. He and Scott and their kids drove north to Malibu Creek State Park. They got there in the early afternoon and were assigned a campsite at the gate. When they arrived Tristan looked around and decided they could do better. So they scouted the campground and found another site, which Tristan deemed perfect. Scott went back to the gate and got them moved, and they pitched camp there, taking turns watching the kids and setting up their two tents.

Afterward, Tristan and Scott made dinner for the kids and then put them to bed. They sat around a campfire for the next four hours, talking. Mostly, Tristan talked and Scott listened. A lot had gone on in his life recently, and more change was coming, and Tristan was just processing the emotion of it all, speaking late into the night.

And then they went back to their tents and lay down next to their children, to await the morning.

Part Two: After

For Erica it might as well have been a meteor—something cosmic and unsparingly destructive. A sudden, random event, followed by the chaotic aftermath of a life she had to rebuild from scratch. And then: a void where a person used to be. A void filled, out there in the world somewhere, by the conspiracy theories and ambient terror of strangers. To Erica, there was no mystery to this mystery: Her husband was gone. No chilling new detail, or elaborate reconstruction of the way he died, was going to bring him back.

And yet in the past year she has had to learn: In situations like this one, people want a story. They want reasons. They want the sensational. They don’t want bad luck, randomness, institutional confusion, simple neglect. But that, to the best of anyone’s understanding, is what happened to Tristan Beaudette. He was asleep in a tent, with his two daughters by his side, when, at 4:44 a.m., someone somewhere fired a gun, and a single bullet, tracing a random but ultimately fatal trajectory, found him. There will be a trial; the state’s suspect has pleaded not guilty. The facts of the case all seem to point to a crime of recklessness. Which isn’t to say it wasn’t murder: Someone fired a weapon into a crowded campground and a man died because of it. But the story, effectively, is that there is no story. No cause and effect. No logic to it at all. If he had been lying down in even a slightly different position, he’d likely still be alive.

“My understanding is that it is a million percent random,” Erica told me. Tristan was “in the exact wrong place at the exact wrong time,” she said. What happened remained unfathomable, even to her. She did not forgive whoever had done it. Someone was at fault. “But all these, like, theories about him being targeted—you know, that raced through our minds, too, at the beginning, like How could this happen? I mean, I had the exact same question. I thought maybe they had run into someone, maybe they had some altercation with someone or something. But from everything I've learned, which is very limited, it really is like getting struck by lightning.”

Erica now lives in a meticulously organized subdivision near the hospital where she works. One day in early April, I visited her there. She was wearing boots, jeans, and a sweater, and looked both very young and somehow years beyond 37, the age she’d turned a few weeks earlier. We retrieved her dog, Milo, a small, slightly aloof ball of white fur, from the carpeted town house where she was living, and walked to pick up her daughters, who were in a day care center nearby.

We walked for a few blocks through gardening plots, past flowering trees. At times, she said, she had visions of this other life that she and Tristan had constructed—deposits put down on a house miles from here, different schools chosen for the girls—that was just out there somewhere, a ghost of the one she was actually living, here among strangers. “When I think about the fact that I'm living here on my own, that I'm a single parent now to a three- and a five-year-old—this isn't what we planned,” she said. “This isn't how it's supposed to be.” The effect, she said, was a feeling of standing outside herself. As if she’d become a character in someone else’s story. “I still feel like I'm watching myself sometimes, you know?”

We arrived at the day care center, and she went in to get the girls while I waited outside with Milo. After they emerged, with auburn hair and backpacks and little cups of granola, we walked over to a nearby playground. Erica said she knew more about raising daughters without a father than she wanted to, because she herself had lost her father when she was young: “For me, I feel like it was a big part of my childhood, growing up without him. It was like the one thing I didn’t want for my girls, you know? One of the first grief counselors I spoke to after Tristan passed, this all came out in the first session, talking about how I grew up without my dad and now, with raising girls without Tristan, and he made some sort of comment about how there's no one else who's better equipped to be their mom right now. And I was like, ‘God, that sucks, you know?’ Who wants to be an expert on grief, or what it's like to grow up without a father?”

Perhaps because of the way she’d lost a parent, she’d always been given to bad premonitions. “I was so worried all the time,” she told me. “I remember I would just have conversations with Tristan: ‘Don’t you worry about this?’ ‘Don’t you worry about that?’ He was just always very satisfied with where he was and what he did.” Erica was never able to let go in quite the same way. “Because I was so happy, I was always kind of feeling like the other shoe was going to drop one day. I don’t know if that’s because of how I grew up. But I was too aware.”

It was a Friday, and Erica had plans to meet one of her sisters, Liz, and her husband, Pete, and their two kids at a nearby Mexican restaurant. Erica collected her daughters from the playground, and we drove to dinner. There the kids discovered a play kitchen in the back, and so Erica went to watch them as Liz, Pete, and I talked. “It feels like eight years ago,” Pete said about Tristan’s death. “But also an inch deep, you know?”

They were all reckoning with the randomness of it all as much as anything else. What happened to Tristan, Liz said, “really changed my outlook on life. The most random, terrible thing can happen to you. No matter what you do.” She said she wasn’t following much about the criminal case. “It’s not going to bring us closure,” she said. Pete said that he had found it harder to let go. At the beginning, after Tristan died, he’d monitored the news about the search for his killer obsessively. But he was working on finding perspective these days. What would happen in the courts would happen in the courts. Whatever the result, “it’s not going to bring Tristan back.”

And yet the question lingers: Was what happened to Tristan Beaudette preventable? Dylan Beaudette, Tristan’s brother, told me he didn’t want to say much before the upcoming trial. But, he said, “I sense that I'm not the only one who's frustrated with how things have happened in terms of the fact that there had been prior incidents and not a lot of notification to the public. And I know the community there is incredibly frustrated with the string of incidents and just the fact that all of these things have happened and there hasn't been a lot of follow-up.”

Tristan’s brother-in-law Scott, who was there at the campground, and who was the first adult to respond to Tristan, told me he, too, was waiting for the trial to see what story the state told about its actions. “But at some point, I feel like there has to be some accountability,” he told me. “There are reports of people shooting and doing things that put the public in danger. And the fact that we didn't know about it—because if we had, we wouldn't have gone. Even if we got to the front gate, if we realized that there were incidents of people being shot at or just hearing gunshots? We wouldn't have gone. We wouldn't have taken our kids there.”

The Wu family’s claim against Los Angeles County and the state of California notes that four different local and state agencies were aware of unsolved shootings in the area before Tristan and Scott went to camp there. Collectively, the claim alleges, the agencies “negligently failed to care and to provide a safe space for Beaudette and his children, instead causing his death.” Anthony Rauda is currently charged with nearly every one of the unsolved shootings—in all, ten counts of attempted murder. The earliest count supposedly took place in November 2016 and involved James Rogers, the wildlife biologist who was sleeping in a hammock when he was shot in the arm. Rogers told me that some time later, after he realized he'd actually been shot—with bird shot, he believes; Rauda was allegedly arrested with a rifle—he drove back to the park. There, he said, the first park employee he spoke with told him “there was a lot of weird activity” in the park and that the rangers “had been told not to be there by themselves and to not go there at night. And just his whole demeanor was like, ‘This is a top secret thing.’ ”

Rogers was referred to a few different people and ultimately made a formal report with a State Park Peace Officer. “But then I never really heard back from them,” he said. He said he’d been in intermittent touch with detectives affiliated with the LASD Major Crimes Bureau. But it was news to him that he was named as a victim in the complaint against Rauda.

“Really?” he said when I told him.

Another woman named in the complaint, Meliss Tatangelo, who had been sleeping in a car with her partner in the area in January 2017 when someone discharged what she believes was a shotgun into the back of the vehicle, told me that she, too, had struggled to get the authorities to investigate what had happened. When she awoke to discover a hole in the back of her car and an apparent slug at the bottom of it, she called the LASD. According to Tatangelo: “The dispatcher was like, ‘Oh, well, that's not our jurisdiction. That's not our problem. Call the State Parks guys.’ ” Two and a half hours later, she said, the State Parks guys showed up. When they arrived, she told me, “I explained the situation and what had happened, and one of them looks me dead in the face and goes: ‘This doesn't happen out here.’ I looked him back dead in the face and said, ‘Well, it did. So what are we going to do about it?’ ”

At the scene of the crime, she said, “they were walking all over everything. There were, like, footprints in the ground, in the dirt—they were walking all over it. We asked them if they wanted to take pictures. I don't think they did. From my memory, they never took pictures. When they pulled the slug out of my car, they weren't wearing gloves. Nothing was done properly. I was expecting to have to give some sort of statement, but all they did was give me their card.” After that, Tatangelo said, she never heard from them again. She waited for some sort of public notice; that never happened, either. “I had to go personally and use my Facebook to write my story to tell the people in my community what had happened.” She tried to alert the local news stations, she said. “But at that point nobody would listen to us. It’s Malibu. Nothing happens in Malibu, right?”

After Tristan died, she said, she commented on a story about his death on Facebook, noting what had happened to her, and “all of a sudden everybody was all interested in it.” Tatangelo remains angry, she said. “Because there was no reason that that man had to get murdered there. There was no reason at all. If the city would have done what they needed to do and at least warned their citizens, he could have made a conscious choice to go there or not. But he didn’t know. And he got the short end of the stick for it.”

She and James Rogers knew each other a bit, she said—Malibu was a small community. “There's no reason that we have to now live our lives looking over our shoulders, when every time a car fucking backfires, I’m jumping out of my skin.” She said she thought there had been an active effort by the authorities to suppress her and Rogers’s accounts of what had happened. “They wanted to cover it up because Malibu is a perfect city. When the first State Parks guy looked at me and said, ‘This doesn't happen here’—right there, I was like, ‘This is bullshit. You guys aren't even going to do anything about this. You're just going to sweep it under the rug because you want to protect your city’s image.’ ”

In early June 2019, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department lieutenant James Royal sued the LASD and Los Angeles County, alleging that he had twice gone to his superiors prior to Tristan’s death, beginning in January 2017, and asked to warn the public. Both times, his suit claims, he was forbidden from doing so—Royal claims his superiors told him it was a “State Park’s problem” and not theirs. After Tristan’s death, his claim alleges, Royal was made to host a town hall for residents, before which he was told to communicate the department’s official position, which was that the previous shootings in the area were unrelated to Tristan’s death. "There is no confirmed connection, and remember, even now there is no confirmed connection," he said at the meeting.

In January 2019, after the Wu family’s “wrongful death lawsuit was filed,” his lawyer, Matthew McNicholas, told me, “and it was confirmed internally that Lieutenant Royal had recommended a warning, retaliation began.” Royal says he was transferred to a different sheriff’s station, considerably farther from his home, and the department opened an internal affairs inquiry, accusing Royal of “interfering with an investigation.” (Citing pending litigation, the LASD declined to comment on Royal's suit.)

It was Royal and McNicholas’s theory that the purpose of the internal-affairs investigation was to intimidate Royal—to either dissuade him from testifying in the Wu family’s civil suit or make him a less credible witness should he be called. “The department turned the power of the badge against one of its own,” McNicholas said. “It is a form of retaliation to control him, so that they are more in control of narrative going forward in the wrongful death lawsuit.”

Meliss Tatangelo told me she had also become friendly with Cece Woods, the local journalist in Malibu who had been covering the case since the beginning and whose work had helped bring to light the amount of incidents that had occurred in the park before Tristan’s death. On her website The Local Malibu, Woods has suggested repeatedly that the LASD was involved in a cover up of the shootings that preceded Tristan’s death. When she and I met for lunch in January, at a Malibu restaurant where she is a regular, her first question was: “How’d you find me?”

Woods is blond and petite and says some see her as part of a lineage that began with the famous Queen of Malibu, May Rindge. “She ruled this town with a freaking gun strapped to her hip,” Woods told me. “A lot of people call me, like, a May Rindge reincarnated—when they're not calling me a cross between Erin Brockovich and Meg Ryan.” She ordered a club soda with a splash of grapefruit juice.

Woods said her connection to Malibu was deep and went back to her childhood, when she moved from New York to California at the age of nine. “We lived in the Valley, but every waking moment was spent on Zuma Beach. My mother was a sun worshipper.” At 22, she said, she married a professional baseball player, and had two children with him. “And I married a few times after that. That's the joke: I don't date. I marry.”

Woods said she got into journalism by way of husband number four, after the death of his girlfriend at the time. This was before he and Woods were together, she said. His partner had committed suicide, and Woods, in her telling, helped clear him of any lingering suspicion authorities may have had. “We ended up getting together not long after that. And the community was calling us murderers—it was bad.”

A few years later, husband number four himself briefly appeared to go missing. Woods worked with a private detective to help locate him. After that, she said, the detective asked her, “Are you sure you don't want a job?” She didn’t, but she realized she might have a knack for a certain kind of investigative reporting. Nearly a year later, Tristan Beaudette was killed. She posted about it, and someone she knew in the Malibu community messaged her: “ ‘Just so you know, four days before, a Tesla was hit at the same time, same place, right outside Malibu Creek State Park.’ And I'm like, ‘What the fuck? Do we have a sniper here now?’ ” Woods began gathering accounts of other shootings and posting them on her site. In turn, the local TV stations noticed her work. “Every news station was after me for an interview. Like, ‘You want to go on-camera and talk about this?’ I'm like, ‘Yeah. Of course I want to go talk on-camera about this. This is bullshit. What the fuck is this?’ Two years they've been hiding this shit. Are you kidding me? I'm a truth seeker. When I find out some other fucker's lying to me, oh, that's it.”

As we sat at the table and talked, her phone pulsed constantly with new notifications. She said that once she began, the investigation took on a momentum of its own and that it consumed her all through the fall of last year. “And that's when I stepped up my tea-leaf readings,” she said. “You've been in the reading three times. You're the only Zach I've talked to at all since then, so I know you're the Zach.” She said that in those sessions, the reader gave her hints, leads to pursue: “She said, ‘The ballistics won't match.’ I don't think they have a ballistics match. If they had a ballistics match, they would tell us they have a ballistics match definitively.

“Four incidents with a shotgun,” Woods speculated, “and at least three of them were inside state parks and not investigated at all.” Woods also had alternate theories about Tristan’s death. “Speculation, too, was that Beaudette was a professional hit,” she said. “And I heard that from guys inside law enforcement. He was a scientist who was researching vaccines, that kind of thing. Must have been close to something, who knows? Yesterday, when I talked to this homicide detective, he's got like an 80-percent-plus conviction rate. He said, ‘It sounds like the guy who committed the murder, and potentially the Tesla thing, hit smack right in the hood to pop it open. That had to have been done with a scope. Somebody knows what they're doing. They've got night vision goggles.’ This guy is not that guy. He's not that guy. Interestingly enough, in my readings, it said, ‘Rifle with a scope.’ ”

Woods had spoken with Erica once or twice, but only briefly; it was sometimes unclear, talking to Woods, where her information was coming from. Her early postings on the other shootings in the area had brought to light a pattern that no one else had seen, at least publicly. But the line between fact and rumor in her reporting sometimes seemed porous—she hinted at things she couldn’t prove and reprinted ominous stories from Malibu residents without further verification.

But Woods was insistent that she believed the authorities had arrested the wrong person. She said that in the days after Rauda was apprehended, she’d seen deputies combing the hills, looking for what Woods thought was a shotgun allegedly used in some of the previous shootings Rauda was charged with. “Even so, let's just say they found the shotgun. How are you going to put that in his hands two years ago, three years ago? And the reports that I got were definitely not Rauda's description. It was a tall, skinny guy who maneuvered very military-like. The description the SWAT guys got was not Rauda. I mean, if Rauda enters any plea but not guilty, he's a fool.”

She seemed sure the real killer was still out there—perhaps lying low now, after the Woolsey fire. “I know there are some bad people out in those mountains,” she said.

“Right after it happened,” Scott told me, “there were so many conspiracy theories. You know—there's very little information out there. So it was easy for people to start putting together these stories, and, you know, if you're the first one that's what people believe. That’s kind of how it works, right? It’s unfortunate, but it’s the truth.”

“The coverage,” Dylan said, “has been a nightmare.”

Other people had theories. But Scott and Dylan and Erica and her family: They had the actual, tangible reality of it. They had to find their way through their loss every day. There was no theory, no neat narrative, that was going to help them do it. Erica said she was aware she and Tristan become characters in any number of stories told by other people. But she didn’t really recognize herself in any of them. “I mean, it's something that is in that alternate reality that I feel like I have no control over,” Erica told me.

We were sitting at the dining room table in her town house after she’d put her daughters to bed. “And I can sort of choose to go down that rabbit hole a little bit if I feel like it or if I have the energy, but then I pull back and it's like, I have to take care of the girls, and we have to get to school tomorrow, and work, and I just don't have the time,” she said. “I’m not really sure what the point of it is.”

Erica admitted that at the beginning, she did try to make sense of it, try out theories, go down rabbit holes. “And it didn't really get me anywhere. And it was just like banging my head against a wall, and me getting really frustrated and not getting answers. And just realizing at a certain point that I had to move on. I think deep down, too, I think I know that no matter what happens, that it's not going to change anything for us. I mean of course if they find whoever is responsible I think that person should be punished. But it's not going to do anything to bring Tristan back, in any way whatsoever. And the girls and I still just have to get up the next morning. I mean… I don't even know how I'm supposed to feel about it. I think I just wish I could turn back time more than anything else. But now that what's done is done, I don't know that anything is going to make a difference.”

She said that the irony was, if people knew what she’d actually gone through—the details of her experience that day were worse, and more surreal, than any theory or fiction a person could possibly come up with. There was the way that she found out, when her sister arrived at the door of her and Tristan’s place in Irvine, at 6:45 a.m., when she was preparing to take her board exam, a test she’d never end up taking. Her sister Priscilla, who lived in San Diego but was there at the door for some reason—Erica said she’s always wondered, wonders to this day, if things would somehow have been different if she just hadn’t answered the door. “I know it doesn’t make sense, but I always wonder, would would’ve happened if I just ignored it? It’s like that weird feeling that you could’ve avoided all of this.”

But she did answer the door. And then came the long ride north to the Malibu/Lost Hills Sheriff’s Station, where her girls were being kept. The officers there, staring at her like she’d somehow become a character on a TV show. The room she and her daughters were reunited in. And then the final surreal touch, when the chaplain at the station entered to offer comfort, and his home, not far away, for Erica and her daughters to shower and change while they waited to go back to the campground.

Except, even amid the chaos and her grief, Erica thought she recognized this man. “I wish I could remember his name right now, but he's an actor,” Erica said. “You know that show Veep, on HBO? He played the vice president. And I recognized him. And he’s the chaplain, and he was there, and he was so kind. And he knew that we hadn’t eaten all morning, and we had no change of clothes. So this chaplain offered to let us come stay at his house, while we waited for word on whether we'd be able to go.”

So that’s what they did—went to the Calabasas home of the journeyman character actor Phil Reeves for several hours, until the police finally let Erica go to the campground where Tristan had died.

After Tristan’s death, his friends and family developed rituals—little things they would do to remember him by or to keep him alive in their minds a little longer. Nolan, one of Erica’s brothers-in-law, told me with some embarrassment about the espresso machine he bought after Tristan died, because Tristan was into coffee. For the first couple of months, Nolan said, “I’d make two and then dump the second one out. It sounds dumb when I say it. But it’s my way to remember him.”

Tristan’s brother Dylan was preoccupied with how people would tell Tristan’s story, now that he wasn’t around to tell it himself. In our conversations, he returned to this idea several times. “I'm struggling with how I can articulate this,” he told me, “but what the coverage so far has been really seems like the angle is shock and, like: Look at this terrible thing—and not necessarily Why did this happen? or Who is this person outside of this?”

On his worst days, Dylan said, he felt like Tristan’s death was emblematic of something darker and more systemic that was happening in the world at large. “The events on that day felt like the physical manifestation of a lack of respect and a lack of compassion and maybe even a lack of acknowledging our fellow man,” Dylan said. “The feeling you get when someone cuts you off on the highway, or when you watch someone throw a cigarette out of the window into a bunch of weeds. Just this blatant disregard for surroundings and other people. That feeling that I know I get of frustration and anger—I had the exact same feeling about this. That someone was, in malice, shooting at a campground, or someone was just thinking, ‘Oh, I'm going to do something, I'm just horsing around.’ Like, basically, that the consequences were irrelevant. And so this felt like, or this seemed like, all of those tiny little instances of someone or something not acknowledging their surroundings, and other people, basically coming to a focal point—and a terrible thing happening. It felt like a societal defect, or a trend, or I don’t even know what—maybe people have always been this way, like they don’t care about their surroundings and their fellow humans and the people around them. Maybe there’s always been a lack of respect. I don’t know. But it seems like a powerful force, or a powerful trend, in our current society. We live in a world where most actions go unaccounted for. Look at most politicians. Look at the CEOs of powerful companies that are involved in terrible tragedies. More often than not, there are no consequences. And this is what happens when consequences don’t matter. And that may just be an angry brother looking for meaning, I don’t know.”

He said in some ways he felt that Tristan, who was competent and modest and thought of others—he was like “the opposite of these kind of things” that were coursing through society, poisoning us all. “And clearly you can't make someone into a saint in an article. I don't think that's a very effective way to communicate who a person was, to list all their qualities. But I think that's what I miss most about him. He had a character that is very rare.”

On May 23, the website for Malibu Creek State Park announced without elaboration that it would be re-opening the campground on Memorial Day weekend. The notice made no mention of Tristan or of Rauda’s other alleged victims. That same day, Cece Woods wrote me, directing me to a new post on The Local Malibu. “Is it safe to go back to Malibu Creek State Park?” she’d written. “Insiders are far from convinced it is.” A young college student’s car had been shot at in the area back in October—after Rauda had been arrested, Woods noted. In March, Monte Nido residents reported hearing gunfire just after 3 a.m. In April another woman told Woods she’d heard the sound of a rifle. “Having spent time on the range,” Woods noted, “she could identify the sound of the gun based on the shot having a slight echo.” Woods obtained what she claimed was an internal sheriff’s department memo, issued the same day it was announced that the campground would re-open, asking deputies to drive through “when time permits,” in order to help calm any concerned residents. Woods also spoke to what she called an “insider at State Parks,” who told her: “The are [sic] rangers are scared and we are in no hurry to see this campground re-opened.”

Woods also thought it was reckless that the park was again open to the public, especially when doubt remained, in her eyes and in the eyes of those she’d talked to, about whether Rauda was in fact guilty. “Upon further investigation,” she wrote, “it seems many, especially those employed by State Parks, are not convinced the murder suspect is in custody. Nor are they convinced that Rauda is responsible [for] the two years [sic] worth of shootings (if in fact they are the same person).”

In a statement provided to GQ, a representative for California Parks and Recreation said: "The safety of our visitors and employees is a top priority. The campground area of Malibu Creek State Park was closed immediately after the homicide. The campground recently reopened to the public. The decision was made in consultation with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and reflects the assessment of California State Parks and local law enforcement that there is no public safety risk at the park."

A representative for Cynthia Barnes, the district attorney trying the case against Rauda, confirmed some basic facts but declined to comment on most details surrounding the trial; so did Rauda’s public defenders. When the case goes to trial, at a date still yet to be determined, the state will finally unveil its theory of the crime. In the meantime, in the absence of information, people would continue to speculate. They’d continue to make up their own minds. There was also the matter of the $90 million civil negligence claim filed by the Wu family, which will eventually be litigated in a State Superior Court. “Law enforcement and the parks system certainly failed to protect the public, and they gave the public no forewarning of the situation that Tristan and his two little girls were walking into,” Erica’s attorney, Victor George, told me. “What is the value of a young husband instantly taken out of life in front of his two daughters? It’s impossible to put a price on, of course. So we count on the jury to do that for us.”

As for Erica, well—she and the girls were getting out of town. June 22 will mark the one- year anniversary of Tristan’s death. It’s also the one-year anniversary of the board exam she never took. So she’s scheduled to take the test this year, on the same Friday. After that, she said, she’s going to fly to Asia with her daughters. She’d just decided this, she told me. She’d already taken the week off—she knew it was going to be hard, and there were things she hadn’t confronted yet, like what to do with Tristan’s ashes, and then a friend had invited her to come join her on a trip, and so she decided to go.

Just that decision felt like progress, she said. “Even last year, when Tristan and I were trying to decide what to do in July, we had thought about it, but we were like, ‘We can't fly with our kids.’ Even with the two of us. But this is how it's different now. I think there's a part of me that just doesn't want to do things like that anymore—put things off or wait, you know? Because what are you waiting for? Tristan and I had put off so many things that we had wanted to do that I regret now. I know I'll be flying alone with the girls, but it won't be the end of the world, even if it's hard. It'll still be an adventure. And at least we'll get away. I don't know—the me of a year ago would never have just gotten on a plane with them and just flown somewhere. But it's going to be fine. And also I think, obviously, I'm trying to get as far away as possible from lots of things.

“I don’t know. It still might be a total disaster,” Erica said. “But we'll see.”

There was no real lesson from what had happened to her and her girls, she said. There wasn’t anything that distinguished them from another grieving family, even. No glint of specialness, of exception. A thing that could've happened to anyone happened to them. And now there was only survival—an arrow that pointed only forward, no matter how much she would like to go back. How to get the kids to school every day? How to keep the memory of their father alive for them? How to prepare herself and them for a trial of the man accused of his death? How to continue to honor Tristan while confronting, head-on, the fact that he was gone?

Scott, who had been there for the end, was still reckoning with that, too. He told me he had photos from the day before Tristan’s death that he still looked at, sometimes. There was one moment in particular he returned to, he said, nearly a year on. It was after the two families arrived at the campground and found their site. They set up a little bit. And then Tristan and Scott took the children down to Malibu so they could play by the ocean.

“My last pictures and video of Tristan are of him on the beach,” Scott told me. “He was going around with the kids, and collecting cool shells and pieces of driftwood and rocks and things, and the kids put them all in this big pile. They had all these rocks and stuff and I took this last video, where Tristan was, like, hurling these rocks into the ocean.” One by one the children lined up, to hand Tristan object after object. “And the kids were just watching it: how far he could throw them out past the waves.”

Zach Baron is GQ's senior staff writer.

Originally Appeared on GQ