Through an Unlikely Friendship, a Refugee Discovers Her Calling

Hawa Diallo is growing more fretful by the minute. She can’t be late for her new job. But the cab driver doesn’t know the town of Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, 15 miles from Hawa’s neighborhood in the Bronx, and he’s circling the streets while she tries to find the address from the caregiving agency. Then she sees a woman standing in front of one of the big, porch-lined houses, smiling and waving both arms. That must be the daughter, Hawa thinks, surprised that someone would run out into a winter night just for her.

Inside, the house is warm, filled with books and paintings. Instantly Hawa feels calmer, comforted somehow. It’s like she’s in her own mother’s house again, though it’s very different. In the living room, Hawa’s new client, Charlotte, lies on a green recliner. She’s 95 and can’t stand by herself anymore, but at times a younger woman seems to peer out of her lively eyes. Hawa strokes Charlotte’s foot and says, “Hi, Mama.” Charlotte smiles and says, “Hi, baby,” as if she’s greeting a beloved returning home from a long trip.

Hawa is relieved. Her previous boss fired her because she forgot one item on the daily shopping list—the first time it had ever happened. The woman said, “I knew you couldn’t read.”

She’d wanted an education badly. When she was growing up in Mauritania, her uncle begged her father to send the smart girl to school. But though her father loved her, he was set on tradition. At 13, she was married to her first cousin. She’s not sure how much older her husband was, at least ten years. After that, she spent her days washing clothes in the river and cooking for him and his brothers. Sometimes she thought, This is not your life.

Hawa has plenty of caregiving experience: all the years she helped her mother tend to her grandmother, who lived to be 105. Now she makes Charlotte the baked apples she likes, cajoles her into taking her eye drops.

She plays African musicians like Youssou N’Dour from Senegal, the Guinean singer Sekouba “Bambino” Diabate. Charlotte sways along with the music in bed. While her client sleeps, Hawa looks at the photos around the room, all of Charlotte at various ages—a little girl, a young mother, regal in her early 70s. Crescent, Charlotte’s daughter, put the photos there to remind caregivers that this frail, elderly woman has lived a long and interesting life. Charlotte, whose last name is Zolotow, wrote children’s books, and Crescent has arranged them all on a shelf.

Crescent writes children’s books, too, and novels and cookbooks. Her name used to be Ellen Zolotow, but in the late ’60s, she changed it to Crescent Dragonwagon. She laughs and says maybe she should have chosen something less flashy.

The family is full of artists. Crescent’s grandfather Harry Zolotow made some of the paintings in the house. They have a big, bright wildness—like the one Crescent calls Harry’s self-portrait, a man whose head is exploding into yellow flowers. Harry was a Russian-born Jew, but Hawa thinks he must have been part African.

Friends are constantly in and out. Hawa’s mother loved to feed people, and so does Hawa, who often finds herself in the kitchen with Crescent, cooking. Hawa is shy about her unsteady English, but food is universal, easier. She and Crescent talk about yam leaves, which Hawa sautés like spinach, and Bulgarian feta, which reminds Hawa of the cheese her mother used to make. They start to talk about other things. The news. Crescent’s home in Vermont. Hawa’s insomnia. One night Hawa tells Crescent that she couldn’t sleep all weekend after she heard about the “cynic” that escaped from the Bronx Zoo. “A cynic escaped?” Crescent says. “A cynic?” Hawa pantomimes, and eventually Crescent understands that Hawa meant “snake.” They’re laughing raucously now, sitting at the kitchen table at 1 a.m.

That’s when Hawa speaks it out loud, the reason she hates snakes. In Mauritania, the men who captured her chained her in a hut with a thatched roof, and snakes slithered through the straw. Sometimes they dropped through the cracks.

It’s been more than two decades since she fled her country in 1989. She thinks she was about 25. The fighting erupted very quickly. All she remembers is the running, the screaming, people being burned alive. Hawa was caught when she went back for her nephew and half-sister. She shows Crescent the scar on her left ankle, where the shackles dug into her skin. The men who held her captive, she says, did terrible things.

Hawa has never wanted to talk about the past with anyone before. It’s best not to put her mind there. In her community, people just say, “It happens all the time.” She always thinks, But it happened to me.

With Crescent, though, she feels free.

The previous caregiver had insisted that Charlotte didn’t like water, but Hawa thinks soap and water are as good as medicine. She figures out how to sit Charlotte on the toilet so she can bathe her and massage shampoo into her scalp. Hawa’s first job in America was in a salon braiding hair, and sometimes it made her queasy, touching the heads of strangers. But with Charlotte, she feels like a mother with her baby.

Hawa doesn’t tell Charlotte much about her life back home. She knows Charlotte is sensitive, that people get more sensitive as they grow older. She saves the horrors for Crescent and the kitchen table.

One of her captors took pity on Hawa, pregnant with her fourth child. She tells Crescent she thinks he may have distracted the other guards to help her escape. She remembers the heaviness of her feet, the wound from the shackles already warm with infection. She ran to get her three children, who were with neighbors. They hid in a wagon surrounded by empty water barrels and made their way to the river, where she found a boat to get them to neighboring Senegal.

She lived there in a refugee camp for four years, buying and reselling fruit to survive. She might be there still were it not for the businesswoman who always stopped to buy from her. Hawa knew the woman must be rich enough to shop in the big markets, but she’d kept coming back because she liked to talk to Hawa. Finally the woman said, “You’re smart. Do you want to stay here selling oranges?” She told Hawa she’d help her however she could. Where did Hawa want to go? In the camp, the Red Cross stocked rice in bags that had pictures of the American flag on them. Hawa said, “I want to go to America.”

The more Hawa talks to Crescent, the lighter she feels. It’s like the moment when you can finally put down a big basket of oranges and your arms go nice and floaty. She didn’t know how heavy the bad memories were until she unloaded them.

Shame is heavy, too, and Hawa has been stooped under its weight. But about a year and a half after coming to Charlotte’s, she finally says it: She’s lived more than 40 years, and she can’t read. Crescent brings her palm to her forehead. The first time they talked, Hawa said, “Show me a recipe one time. It’s not going to be twice.” Now Crescent understands why: She never wanted to hear, “Look it up in the cookbook.” Crescent promises to help Hawa find a tutor, and Hawa feels hopeful. Maybe someday she’ll read Crescent’s and Charlotte’s books.

Crescent teaches a weekend writing workshop, and she asks Hawa to come along: Hawa can help with the cooking and also be part of the class, called Fearless Writing. Sometimes people have stories they are burning to share with the world, Crescent says, but when a story becomes too important, the person can become afraid to write it. They worry that the story will shrink in the telling, or that others will tear it down or ignore it. They come to Fearless Writing so they can stop thinking so much and just tell the story that wants to be told. Crescent gives the class writing exercises.

In a quiet corner, Hawa dictates while Crescent writes down what she says. One exercise is called Sacred Lists: List 15 things you know about a given topic—insects, haircuts, lawnmowers. Today it’s birds. Hawa thinks of birds. She talks about the birds she sees on her walks in the neighborhood. She talks about the ones she remembers from Africa. Then she laughs and says, “I guess you could say a big metal bird brought me to you and Charlotte.”

The next day, the class does a 15-minute drawing exercise. It’s just a rarefied form of doodling, meant to loosen everyone up and, as Crescent puts it, “release the emergency brake.” It’s like meditation—making lines and circles, lines and circles to form a pattern.

Hawa has never drawn before. She has rarely even held a pen. She begins to make curves and flourishes. She has never made anything for its own sake, a thing meant simply to be beautiful. But now her hand glides over the page. She has only to imagine the next line and there it is. Hawa is falling away from the world, into a place she goes when she dreams at night. She has always had vivid dreams.

When the 15 minutes are up, she signs her name at the bottom of her creation. Her children taught her how to sign her name. Everybody puts their drawings in the middle of the table, and someone in the class asks Hawa, “This is the first time you’ve done this?”

Here is one more thing Hawa knows about birds: A stranger once told her that one day she’d fly like a bird. Over the years the words have been a pleasant thing to keep in her head, like a snippet of a song, but she’s never been sure she believed them.

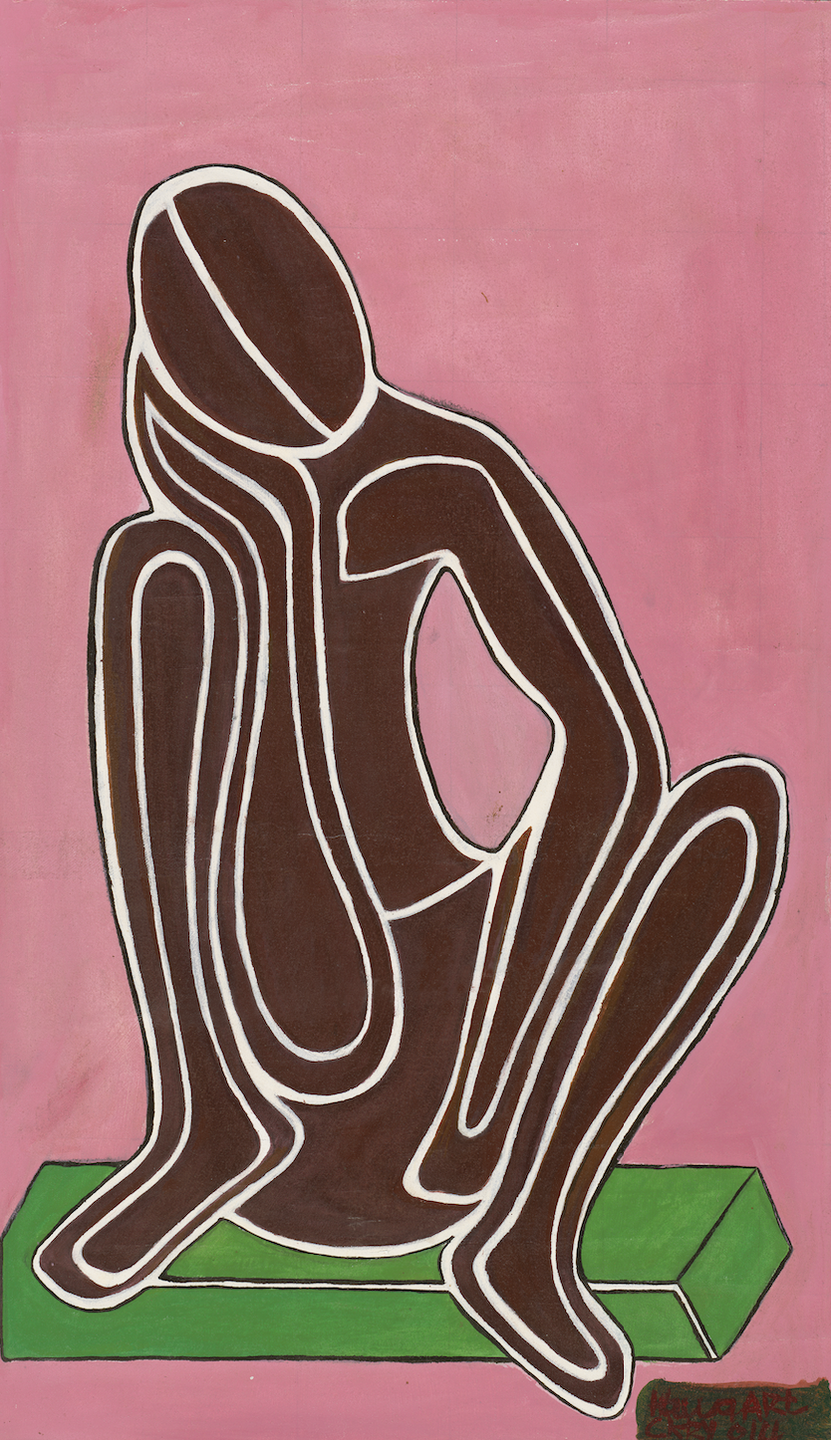

After that, Hawa never stops. She can’t stop. She makes more of the tangled abstract patterns, some with the letters of her new alphabet. Now her mind fills with colors. She goes to an art supply store for paint. When she holds a brush, she’s no longer defined by what she’s not—not a man, not literate, not someone with money. Painting is about what is, what’s inside her.

The pictures come out of her head like a waterfall, so many ideas she thinks she might be going crazy. She wants to paint people, but as a Muslim she was taught that it’s wrong to draw images of humans. She practices making figures, only on pieces of paper that she doesn’t show anyone. But she comes to understand that if God created her, he must have given her this ability, and why wouldn’t he want her to use it?

She paints Africa then: scenes from the village where she grew up, the palm trees, the mosque. She misses the country of her childhood, before the fighting—her mother and father, the sounds of the children playing at night. Now she’s able to go back.

She draws a snake slithering through a swirling design, with a V shape of flowers at his throat. Hawa knows he’s running from a woman who’s trying to choke him. She used to be afraid of the snakes. Now the snakes are afraid of her.

Charlotte is one of Hawa's biggest supporters. She’ll ask, “What are we working on tonight, honey?” And Hawa will say, “Well, Mama, I have an idea.” The two of them are always talking about Hawa’s paintings, even when Charlotte is sleeping and Hawa is working quietly next to her. The conversations happen in Hawa’s mind, in the place where the dreams are.

Crescent doesn’t tell Charlotte about the bad things that happened, and Hawa doesn’t either. She doesn’t need to. Charlotte knows her whole life already, the way Hawa’s great-grandfather, a wise man, knew things without being told.

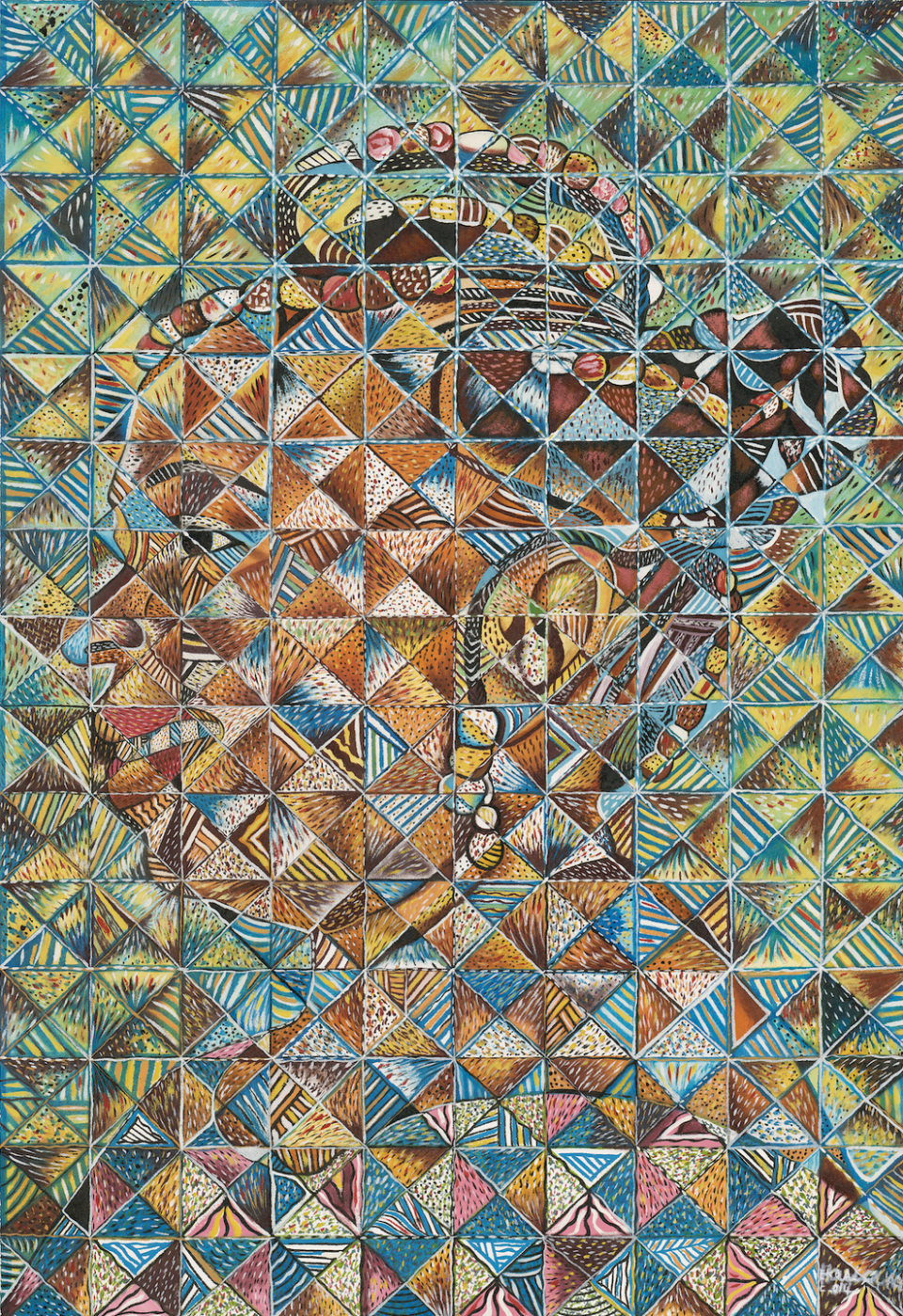

One night Hawa makes a piece about the home she’s found with Crescent and Charlotte. She paints tiles for the house she loves, rectangular shapes for the train that brings her there every day from her apartment in the Bronx, swooping lines for the George Washington Bridge, which she sees from the train window.

Charlotte’s eyesight is failing, so Hawa has to tilt the painting back and forth until she can focus. Hawa says, “I love this painting, and I think Crescent would love it, too.” Charlotte closes one stiff hand into a fist, holds it to Hawa’s chest, and says, “But what about you? How does it make you feel inside?” Hawa takes a big breath, lets it out in a whoosh. “Like a bag of cement has been lifted from my heart.” And Charlotte says, “Then I guess my work is done. It’s time for me to leave.” Hawa asks her where she thinks she’s going. She’s not going anywhere! That night the only place Charlotte goes is back to sleep.

Six months later, when Charlotte really leaves, she doesn’t make any announcement. She just slips away. Hawa is sure she’s only sleeping. But when she gets close, she can see that Charlotte’s eyes are open a crack. Though Charlotte went blind a while ago, now her gaze is focused, as if she’s looking at something a little to her left. She’s smiling. What did she see?

Charlotte passed so easily, Crescent says, like a leaf falling from a tree. That day Hawa starts a painting with shapes like falling leaves. They’re Charlotte’s footprints.

Now Hawa faces another ending: She’ll be leaving this house. The life she’s had here, the things she’s created—maybe it was just another one of her dreams. She makes a painting that’s thickly lined like notebook paper, the lines filled with shapes that might be houses, or worried eyes. Hidden in the shapes are Ds for Diallo, Ws for her questions: Where will I go? What will come next?

In the days after Charlotte's death, Hawa can’t stop thinking about one particular photograph of her, a close-up taken in her early 30s. Charlotte’s chin is resting on her hand, and she’s smiling slightly. She’s looking at something a little to her left. What does she see? With her phone, Hawa takes a picture of the photo so she’ll have it to keep.

From the picture, she creates a portrait of Charlotte. She paints the shadows on Charlotte’s face, the folds of her dress. It’s the most realistic work she’s created so far, the art that looks most like life. Then she adds little bunches of wildflowers around Charlotte’s head, a radiant burst of gold behind her. Publishers Weekly runs a photo of Young Charlotte on its website along with the story on Charlotte’s memorial service. There’s Hawa’s work among all the famous writers and their books.

Hawa wants to paint all day. Sometimes she has three projects going at once so

she won’t waste paint. It’s like tending to three pots of food on the stove. She makes collages, like the one of her mother carrying a basket of peanuts, with actual shells glued to the canvas. Abstract paintings with swipes and splotches, bright folk-art scenes, blossoming designs on satin. That’s what artists do, move through different periods of their work. Hawa’s just going through all hers at the same time.

Sometimes she gets up at 4 in the morning so she can paint her dreams. Long before she knew she could make things, the dreams were her art, the worlds that lived inside her head. Now she talks to the paintings as she dabs at the canvas, thinks about what the dreams might mean—the trees and grasses in the place she was born, a flower with a face on each side. Only one face shows in the painting. That’s Crescent’s. The one on the other side, the one no one can see, is Hawa’s. Only she has to know it’s there.

Often she hides figures or objects in the paintings. She paints a grid of squares filled with dots and stripes. Step back to take in the whole, and you find a portrait of Hawa. She decides to call that one Hidden Talent: Jubadeh. Now when she hides things, she’s saying, “Look closer.”

Six months before she made her first drawing, Hawa dreamed about Crescent’s grandfather, the painter. Crescent had told her that Harry did piecework in a factory before he discovered he was an artist. In the dream, he gave Hawa and Crescent each a box filled with gold bangles, weighty and shining. She said to Crescent, “What are we going to do with this gold?” Harry told both of them, “Just keep it.”

Hawa thinks she knows now what the gold was. After Charlotte died, someone asked, “How much did they leave you?” She leaned back, smiled, and said, “A lot. So much, I can’t even tell you.”

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like