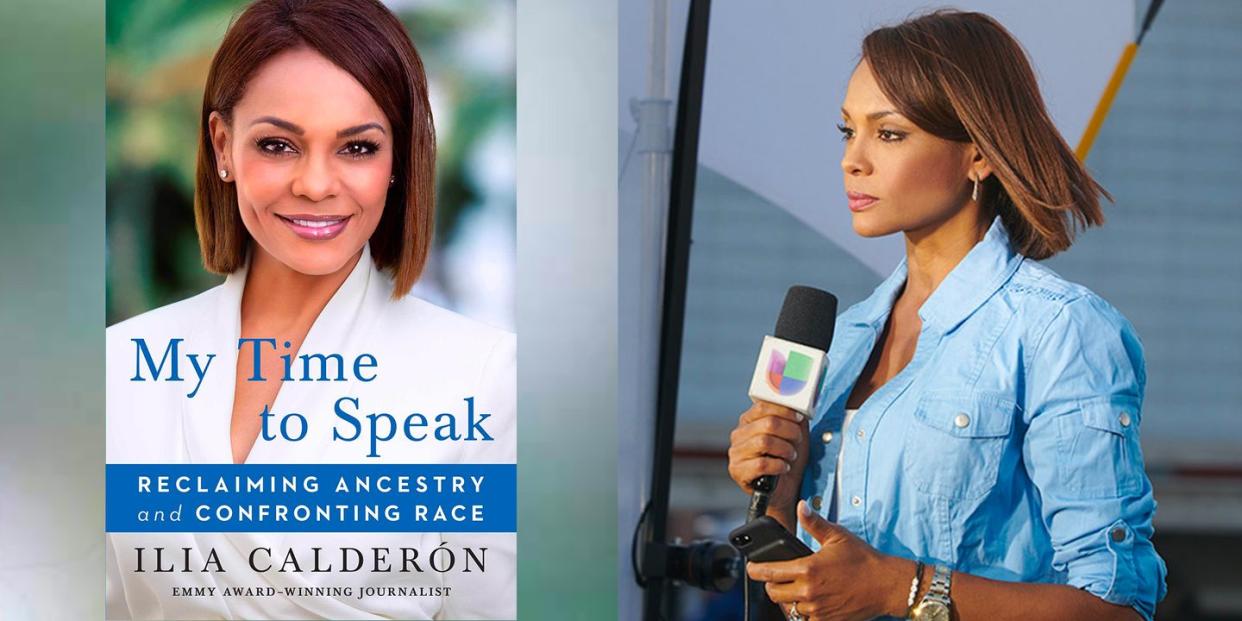

Univision's Ilia Calderón Says People Often Don't Believe She's Latina

Ilia Calderón is the first Afro-Latina to anchor a national newscast in the U.S.

In her new memoir, Calderón unpacks her identity as an Afro-Latina; her history-making interview with a hate group's leader; motherhood and marriage; and her role as a journalist in a divided America.

Below, Calderón speaks about her first months in the U.S. after moving from Colombia

In 2017, the Univision news anchor Ilia Calderón made headlines herself after interviewing Chris Barker, a Ku Klux Klan leader in North Carolina. He coldly informed Calderón, a Colombian immigrant and U.S. citizen, that she was the first Black person on his property in 20 years, and threatened to "burn" her. Voice unwavering, Calderón held her own during the altercation: "My skin color doesn't define me," she said.

It's only in the opening of her illuminating memoir, My Time to Speak: Reclaiming Ancestry and Confronting Race, that Calderón admits to the fear she felt in that moment, facing down an extreme version of the racism that has been a constant her entire life.

"I sat in front of hate personified, at the mercy of the very hate I’d always wanted to look in the eye with the hope of finding answers to the many questions I’d had since I was a child. Why do they reject us? Why does skin color define us? What is the source of such pure hatred?" Calderón asks in the book's opening pages.

Throughout My Time to Speak: Reclaiming Ancestry and Confronting Race, Calderón addresses how her race intersected with her ambition—first, as an Afro-Latina in Colombia hurt by schoolyard teasing; later, as an immigrant to the U.S., part of a marginalized Latinx minority, and then as the first first Afro-Latina to anchor a national newscast in the U.S.

Calderón was born in El Chocó, a region in western Colombia known for its beautiful beaches, incredible biodiversity—and the highest poverty rate in the country. The region is also home to a majority Afro-Colombian population, of which Calderón is a part.

"There’s no doubt: I, Ilia Calderón Chamat, am Black. Colombian, Latina, Hispanic, Afro-Colombian, mixed, and anything else people may want to call me or I choose to call myself, but I’m always Black. I may bear Castilian Jewish and Syrian Arab last names, but I’m simply Black in the eyes of the world," Calderón writes.

When she moved to Florida in 2001 for a job with Telemundo, Calderón encountered many shocked to learn that a person could be Colombian and Black. She describes the leap from Colombia to the U.S. in the period around 9/11 as a "triple jump from a trapeze without a net." Facing language and cultural barriers, even a trip to the grocery store could "plunge [her] into despair."

In the excerpt below, Calderón describes her specific experience with the kind of culture shock that many foreigners will find familiar. "It’s a stage all newcomers suffer to a greater or lesser degree; those who’ve experienced it will understand me perfectly," she writes. Her difficulties were only exacerbated after 9/11—when her other last name, Chamat, roused suspicion.

The clerk spoke to me in a rapid-fire English. When I begged her to continue in Spanish, or to speak slowly, the woman—Black and in her fifties—put on her glasses to get a better look at me.

“Honey, don’t tell me you don’t speak English,” she said.

I immediately got what was happening: she thought I was a Black American, like her! Or should I say “African-American”? In that moment, I realized Black Americans saw me as a Black American. I soon discovered that, though I felt so Colombian, I didn’t look Colombian—even to my own Colombian compatriots who’d been living here awhile.

“You’re Colombian? Really?” they’d ask, not hiding their surprise at the store, the doctor’s office, or in a restaurant. “I could’ve sworn you were American, that you didn’t speak Spanish.”

Some people would ask me if I was Dominican or Puerto Rican. Others told me my face was very typical of here or there. They always found a reason to catalog me as anything but Latina, much less Colombian. I simply didn’t look like the prototype everyone saw in all those successful evening soap operas from my country. This hit me hard because, all my life, I’d felt more Colombian than coffee, than arepas, than bananas and my Chocoana jungle.

The question that always followed inquiries about my origins was: “But...there are Black people in Colombia?” Before saying, “Yes, of course,” I’d take a deep breath because I didn’t want to sound rude. I soon realized we only had ourselves to blame for this line of inquiry, because we, Colombians as a nation, had been whitening our history for so long—until that day we even bleached that portrait of the illustrious Juan José Nieto Gil [ed note: Nieto Gil was the only Black president of Colombia].

How could I blame the world for not knowing we existed if we didn’t appear in our own novels, or the international marketing campaigns for Juan Valdés and his rich coffee, or anything at all we exported! How could I expect a New Jersey or Kentucky neighbor to know what color we were in El Chocó if he didn’t know where El Chocó was to begin with? Even other Latinos during Miami’s party-ing and glamorous nights would take a break from dancing to Grupo Niche and then act surprised to see me on the dance floor, with my dark skin and Colombian accent. Never mind that all the members of Grupo Niche look like me!

From the dance floor to the streets, the stories didn’t stop. Even my mother, when she finally came to see me, fell right in. “Look at that Black man driving that expensive car,” she said. “You don’t see that in Colombia!” In her head, there was no image of an Afro-descendant man with money, unless he was an athlete or an artist. But in Miami, Afro-descendant people ate at expensive restaurants, bought at fashionable stores, and no one seemed surprised. I attributed these differences between being Black here and being Black there to the fact that, on American soil, we could leverage the historical activism I spoke about earlier.

In Colombia, we hadn’t suffered official repression like in the United States, so we hadn’t benefited from a civil rights movement as complex and revolutionary as the one this country—with its great achievements and great contrasts—had experienced in the 1960s.

In short, in this new world where no one could guess my nationality, at least there seemed to be more opportunities, although, obviously, it’s never been and isn’t yet the promised land of equality or equity, and there are still many struggles to fight for and win. Recently, what’s stuck in my head is the image of two mounted police in Galveston, Texas, leading a young Black man with a rope. An act of humiliation, a total lack of humanity, a vision that reminds us of the dire years of slavery. The office where the two agents were assigned offered apologies and promised to eliminate the practice so that such an outrageous act wouldn’t be repeated. I couldn’t even believe this was still legal and accepted in the twenty-first century on American soil!

Despite some of the patterns of discrimination sadly being repeated, the opportunities I always talk about are a little more present here compared to Colombia, where Black people seem to be doomed to be poor and happy in our poverty.

A la venta en tiendas #EsMiTurno. On sale now #MyTimeToSpeak

A post shared by Ilia Calderon. (@iliacalderon) on Aug 4, 2020 at 1:52pm PDT

In our countries, they’ve sold us an image, as cruel as it is false, of the Black man content being poor, spending his days cheerfully sing-ing and dancing, his feet in the sand, without a dime in his pocket. It’s a great lie, created to justify the lack of opportunities affecting these communities. It’s not that our people don’t want to surpass themselves, or don’t know how, it’s simply that access to education and well-paid jobs is limited, almost null. With zero possibilities and corruption at all levels stealing monies allocated to the most disadvantaged communities, of course people are stuck in poverty!

Once poor, they do the best they can. But we can’t let ourselves think they’d rather be out dancing salsa instead of going to college or starting a business. That’s an archaic, imperialist, and neocolonialist vision, worthy of those gentlemen who hid Nieto’s portrait in a basement so no one would see a Black man with a presidential sash across his chest.

Back on the streets of Miami, and despite my mother, who saw good things in my new country, doubts assailed me: Had I come to the right country? Would I have gotten further ahead personally and professionally in Colombia? The stress of September 11 and the subsequent whirlwind of information in which I was trapped on my arrival made me hesitate, especially because everything had changed.

The entire country was transformed by September 11 and its aftermath: new fears, new rules and laws, a new economic situation, and new xenophobic and anti-immigrant feelings. Everything that sounded Arabic awoke fear and distrust. Discrimination against the Islamic world joined and at times surpassed the classic and entrenched rejection of Black people.

This new scenario made me reconsider my second last name, Chamat, which sometimes aroused suspicion at airports. I come from a country with a large Middle Eastern community. To talk about Colombia without including Syrian-Lebanese contributions is to refuse to see the full picture. My paternal great-grandfather was one of those thousands of so-called Turks who landed in Cartagena at the end of the nineteenth century, fleeing the Ottoman Empire. Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine remained under Turkish rule. Rumors about new and exciting countries on the other side of the Atlantic, where they could be free, gave them the courage to sign up for one-way trips.

For the most part, they were enterprising young men, commercial vendors in Barranquilla, Cartagena, and Bogotá. Over the decades, they opened their first businesses selling fabrics, threads, and all kinds of things. In the mid-twentieth century, the Syrian-Lebanese community was able to scale the country’s social hierarchies by sending their children to college and establishing successful businesses. So it wasn’t strange to find Arabic last names among great doctors, lawyers, intellectuals, and current politicians. Don Carlos Chamat and his tiny shop in a corner of El Chocó, the son of one of those pioneering and adventurous Syrians, and of the Afro-Colombian woman who fell in love with him, was part of that wave.

Now, here I was, traveling the world with an Arabic last name and black skin. When I was questioned at immigration checkpoints and I risked speaking English, my strong accent didn’t help and caused even more disorientation. I decided to answer in Spanish to make my origins clear, “Yes, I’m Colombian, of course I’m Colombian...yes, there are Black people in Colombia...yes, how curious, true...” I’d have the same conversation over and over, like a scratched record.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like