How to Unfriend Your Dead Brother

Something curious happened on the way to my brother Andrew’s funeral: He FaceTimed me. Three days after his fatal car accident, my phone buzzed with a familiar jingle. Andrew MacLean is FaceTiming you. It was the call I didn’t realize I’d been waiting for. I answered, disbelief eagerly suspended. A familiar voice leapt out: “You on your way?” It was almost Andrew. Almost. My other brother Gregory’s voice sounded so similar to Andrew’s over the phone that for one glorious moment I believed it was him. “I lost my phone, so I’m calling you from this laptop.…” I snapped back to reality. Andrew was dead. Greg was calling from Andrew’s laptop. Video conferencing from the other side was not yet an iPhone feature.

New to grief’s first stage, denial, I’d fallen for the ultimate crank call. Andrew would’ve gotten a real kick out of it if he’d been there. Andrew was a nurse, someone who provided disaster relief around the world. When there was a tsunami in Sri Lanka, Andrew went. When there was an earthquake in Haiti, he dropped everything. He was my eldest brother, a relief worker. He’d struggled with addiction since he was a teenager, and I lived for years half braced for that call. But when it came down to it, I’d sooner accept that a dead guy was giving me a ring than that the guy was dead in the first place. His digital ghost had pulled a fast one on me—and not for the last time.

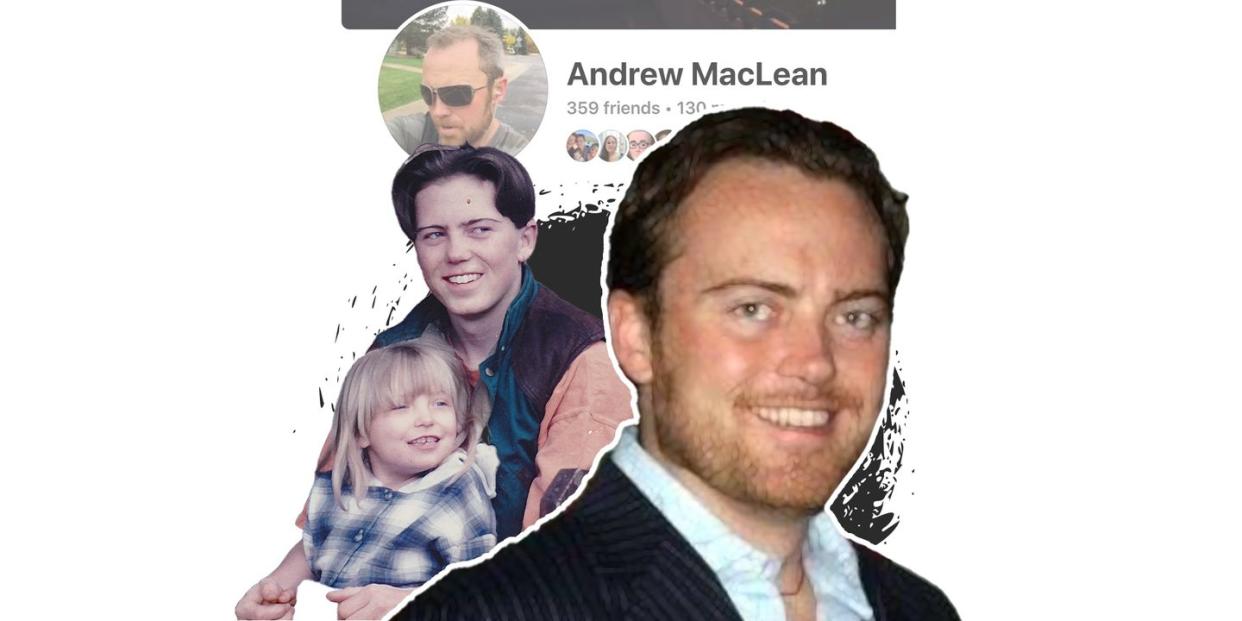

As months passed, I attempted to accept Andrew’s death, but his digital self refused to. By all accounts—literally—he lived on. Andrew MacLean wanted to “connect” on LinkedIn—real bad. For the year after he died, the platform suggested we connect multiple times, each time triggering longing for that very thing–and a downward spiral of regretting not doing so more when he was alive.

Reminders of his birthday appeared on my Google calendar, as if I could forget that November 22 was the day Andrew was born, or that on that very same date four years later our brother Gregory was, too. Facebook took it upon itself to remind me repeatedly, as if I could forget the day that a relapsed Andrew was doing some early celebrating and skidded off an icy bridge into a half-frozen pond just after midnight on his thirty-seventh birthday. I wished I could fast-forward over that day, erase it like the thirteenth floor of a skyscraper. “November 22nd is Andrew MacLean’s birthday!” No shit.

Evite and Facebook kept nudging me to invite Andrew to things—his name permanently topping my “suggested” list. Is it because we have the same last name? Had. Because his name started with A? If he were a Xander, would I be having this problem? It’s been seven years since he died and yet my phone still autosuggests “Andrew” every time I write “and”—about six hundred times a day. When did technology become the guy who casually brings up traumatic events without noticing he’s crippling you?

After Andrew died, I had to teach myself to switch off the grief so that I didn’t find myself sobbing against a water fountain because Andrew hydrated, too. I bottled up the pain until there was an appropriate amount of time, space, and perhaps an actual bottle in hand. But social media continually sieged my last bastion of power: the power to forget. People speak about the first stage of grief condescendingly, but it probably saves lives. Following a tragedy, the brain releases a veil of fog to protect itself. The brain becomes Teflon: The truth doesn’t sink in, it just slides off.

Case in point: Largely, what I remember from Andrew’s funeral is feeling vexed that someone brought electric-green Jell-O complete with dollops of Cool Whip and maraschino cherries. Most offensively, it sat on a bed of iceberg lettuce. Someone heard my brother died and thought, This is the moment to resurrect a violently green dessert salad that should have never made it out of the fifties?! I wasn’t ready to be mad at Andrew; I wasn’t ready to be mad at myself for not saving him. But what heinous asshole brought the desert salad? Fuck them.

The intersection of grief and tech wasn’t always bad, but its timing was. About a year after Andrew died, I discovered my Facebook “friend request” messages. They were studded with people reaching out about Andrew in the months that followed his death. Each one a gem glittering with love for Andrew, stories of how he’d helped someone, or how he’d bragged about me. One message from a man in Haiti told me that Andrew had saved his sister’s life—that “in our village, Andrew is a hero.” Andrew hadn’t even mentioned this girl, meanwhile I brag for days if I volunteer to switch seats with someone on an airplane. I took the rest of the day off work to cry about how Andrew saved people’s lives. At least if I died, my family wouldn’t have to field messages about what a hero I was.

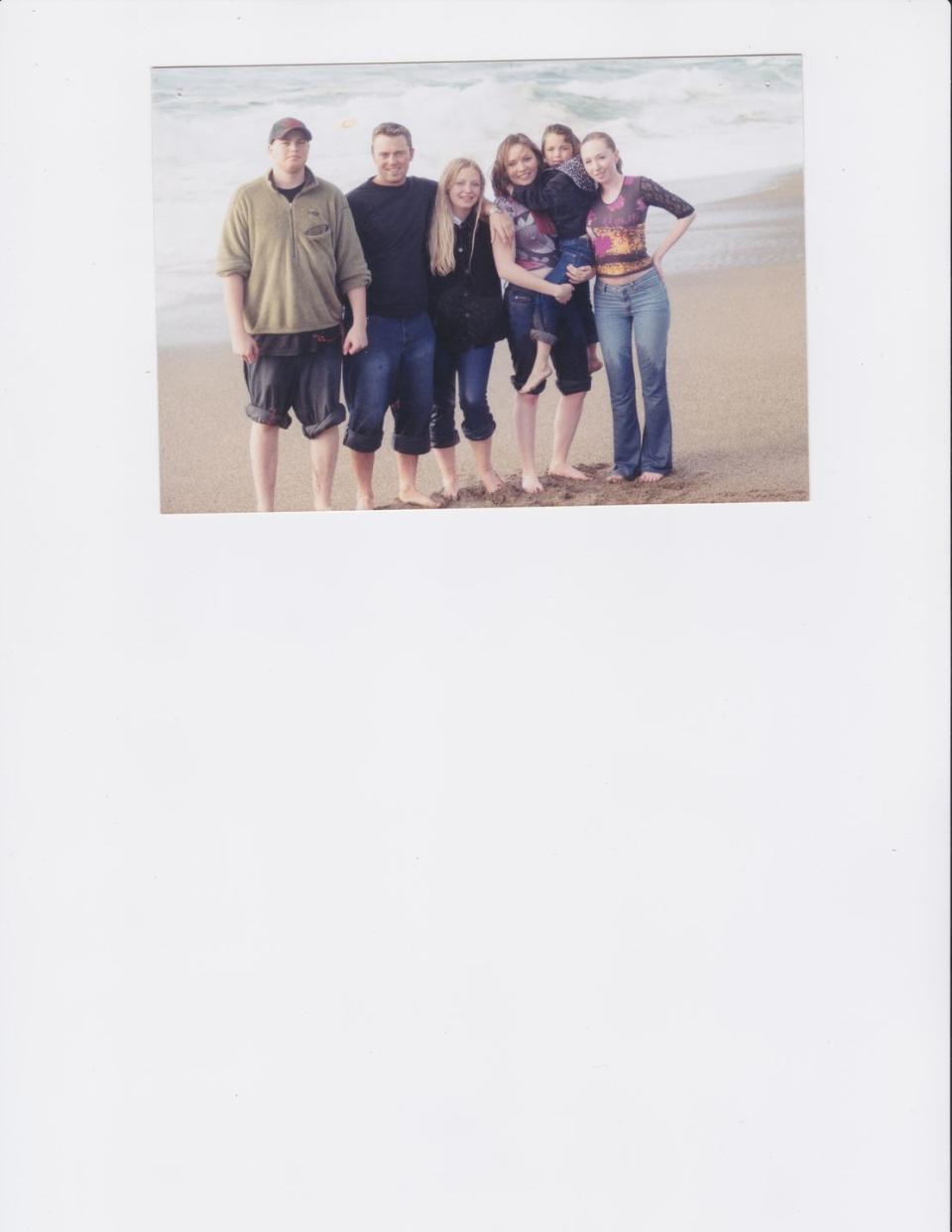

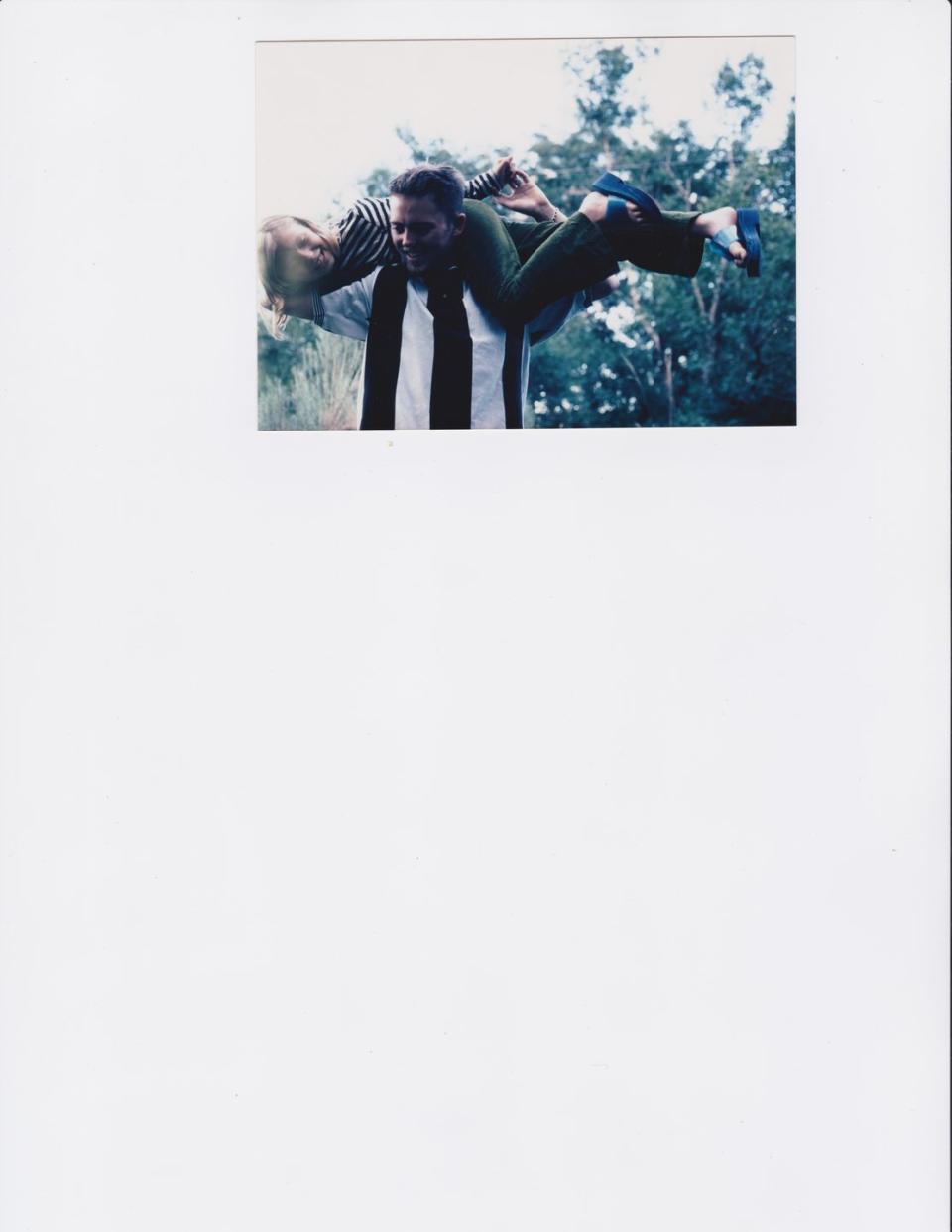

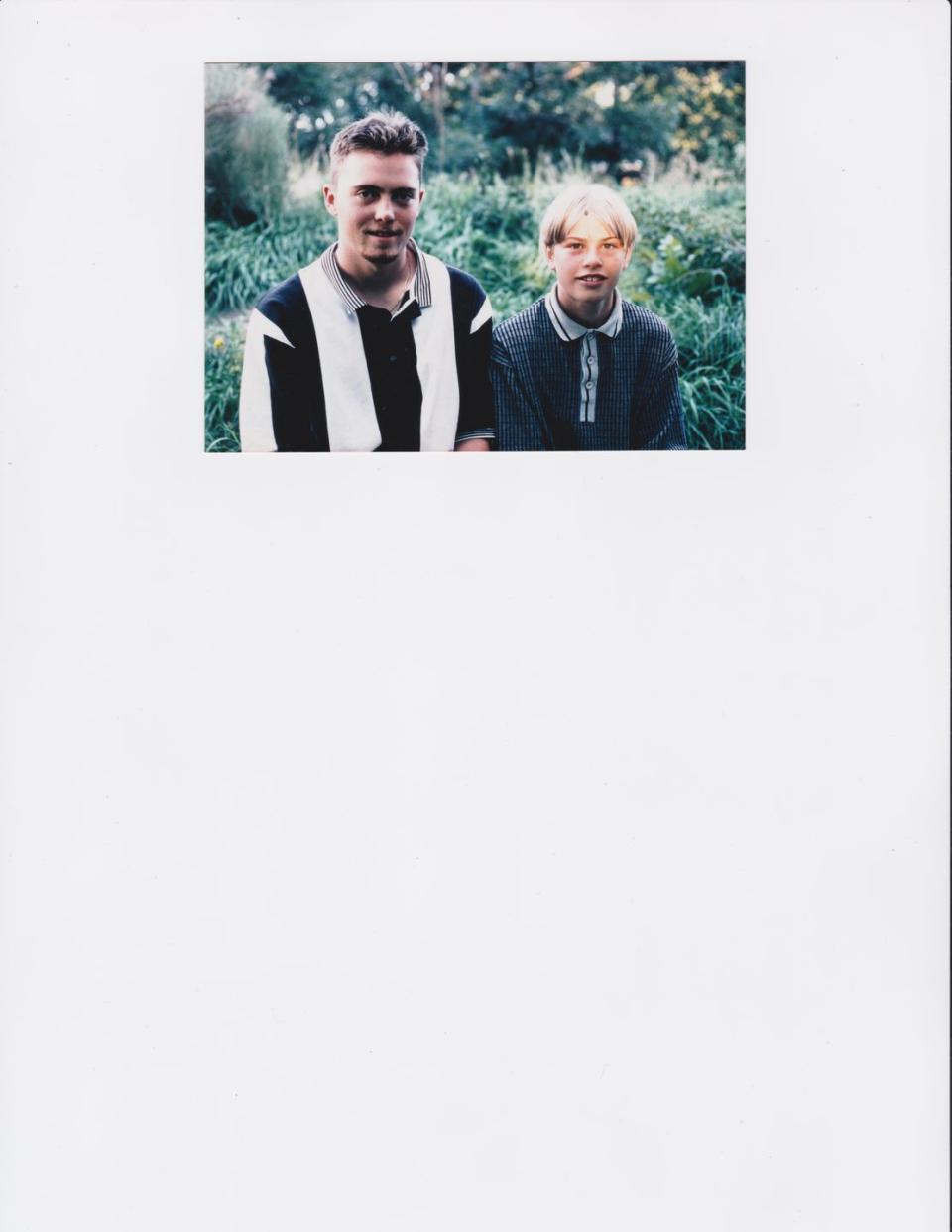

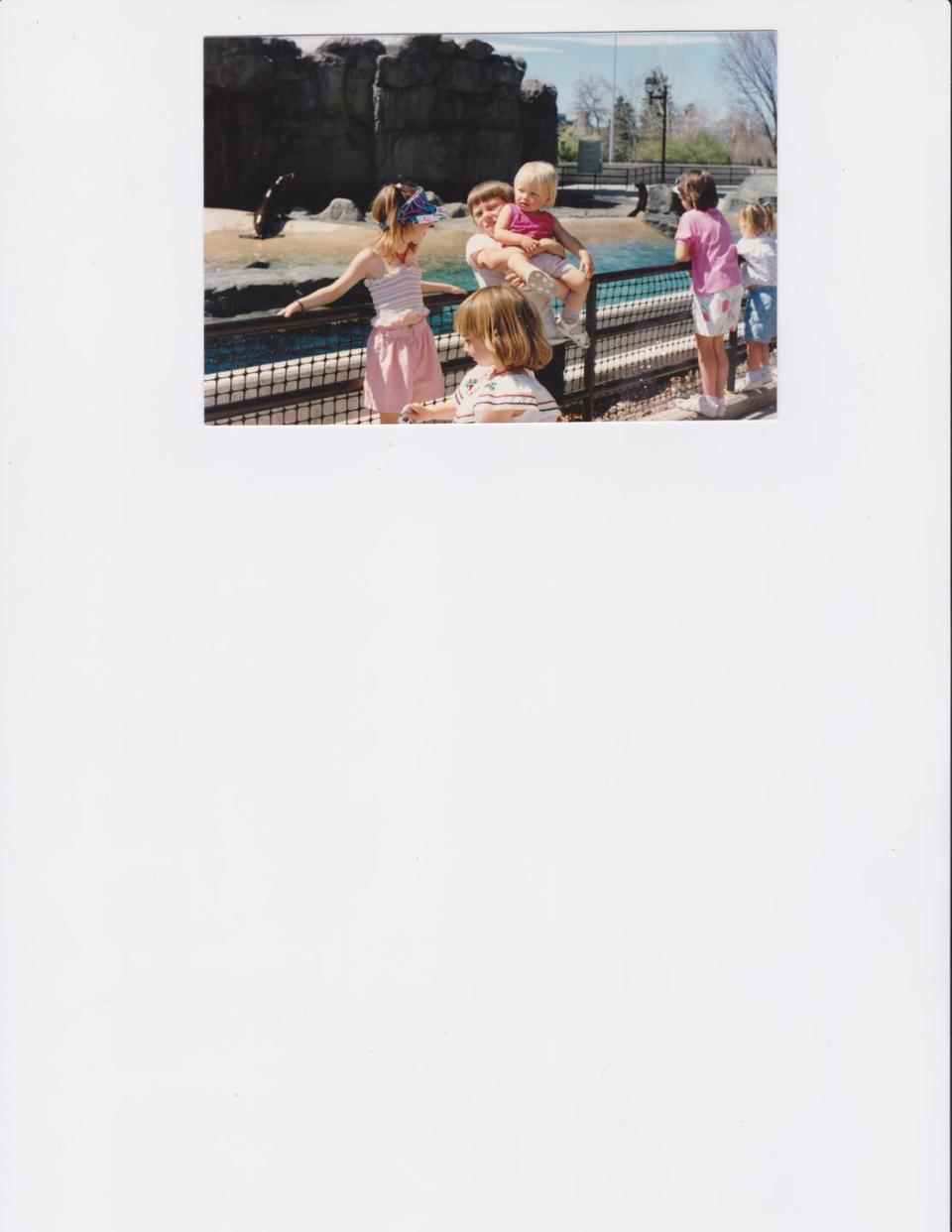

Not long after, I got a notification from Facebook that it was my eight-year “friendaversary” with Andrew and, wouldn’t ya know it, they had made a video to celebrate! I knew not to press play, but I did it anyway. A montage of images of my brother and me as kids together unfolded. Though we were half siblings, the pictures told the story that I was ever his charge. Dangling off his neck in an uncomfortable-looking piggyback. Perched on the handlebars of his bike. Me on his lap, always on his lap. And, of course, that photograph in which we are all grown up, our arms around each other, with twin smiles and, somehow, zero MacLean double chins between us.

Punctuating these images were stock comments from Facebook corporate, like “You seem to like each other a lot,” and “Although there are millions of friendships, there’s only one like yours.” As I read them, I broke into a shaky smile. Here really was only one friendship like ours. And somebody—albeit a robot—knew.

The final big reveal of the video came in the form of a friend’s comment on a photo of Andrew and me, randomly selected by a bot from a thread of a picture I posted of us when he died. It dropped down dramatically at the end of the video. Surely whoever wrote this algorithm figured the comment would say something fun like, “What a couple of hotties, I want to bang your whole family!” But instead it read, “I’m so sorry for your loss :( ” punctuated by a peppy cartoon “boing!” complete with gyrating cartoon characters. It was a level of macabre horror that David Lynch himself would not dare.

Then there are the various messenger platforms in which we corresponded. I go back to Andrew’s messages sometimes and they look as fresh as today’s missives. Unlike an old postcard, there’s no yellowing around the edges. No dust. It’s not buried at the bottom of a stack of paper indicating the slow passage of time. One finger flick away is the rain check of a coffee date that would never happen. “Andrew MacLean,” with a profile pic he snapped to show me his new haircut–boldly embracing that his hairline was in retrograde. That image would hang in permanent suspension: a coming-out-of-the-balding-closet selfie. What do you want on your virtual tombstone? Probably not that.

Andrew never had Instagram and didn’t live to see TikTok–I’ve been spared seeing his virtual self trapped doing a white-guy jig pointing to lines of text like it’s the Macarena. Now, that would be too much to bear.

Apparently, you can request to memorialize a person’s Facebook page, but like the obituary we could never bring ourselves to write, we’ve shied away from making Andrew’s death official. Perhaps I’ll finally block his various accounts; ghost the virtual ghost. I don’t need to see the awkward handful of birthday messages on his Facebook wall that echo each year like scattered applause at an open mic. I don’t need to be reminded to invite him to parties. And I certainly don’t need a cartoon character twerking over a robot-generated slideshow of us. Then again, unfriending him would mean never getting contacted by him again. Part of me clings to these virtual run-ins. They’re almost Andrew. Almost.

Two and a half years after Andrew died, lightning struck twice. My brother Gregory, who’d struggled with schizophrenia and agoraphobia long before Andrew died, and with crippling grief after, took his own life. It was the Romeo and Juliet of brotherhood: Born on the same day, Gregory didn’t want to be here if Andrew couldn’t. He followed him into this world, and he followed him out. Self-destruction and suicide sometimes cluster in families, a grief counselor told us, too late.

Grieving Gregory was a profoundly different experience on many levels, in part because Greg didn’t have social media. No Facebook profile; no LinkedIn or Dropbox with which to nudge me posthumously. Instead of my brother jumping out at me from a pop-up window like a zombie from a corn maze, he comes to mind organically: Finding a lobster in the La Jolla tide pools he loved. Getting caught in a torrential thunderstorm–the kind that mirrored and soothed Gregory’s turbulent mind. Standing on a snowy hill, I remember him at the top of a Black Diamond trail, pointing his skis straight downhill like it was nothing. I think of him when I make a pie from The Pizza Bible he gave my husband and when I wear the gem earrings he bought me on his last Christmas, though he really couldn’t afford them. They don’t jump out of the jewelry box like a snake-in-a-can; like my memories, I take them out when I’m ready to face them.

A couple years back, I visited the mountaintop where we scattered first Andrew’s and eventually Gregory’s ashes. It was November 22–as no less than six calendars had reminded me–their shared birthday and the anniversary of Andrew’s death. That grotesquely layered day. Death within death. A Turducken. I was speaking aloud to my brothers with a saccharinity I spare the living when a heavy gust of wind nearly bowled me over. I stumbled, then laughed out loud. It was the brotherly shove they would have given me if they were there—a cosmic noogie. Not exactly a FaceTime call, but a dispatch from the other side nonetheless. I felt their presence, I felt our bond, the usness for which Facebook wishes it had an algorithm.

You Might Also Like