This Undiscovered Region in Spain Has 11 Michelin-starred Restaurants — Here's Where I Ate While Visiting With a Famous Chef

Chef Eric Ripert visited Castilla-La Mancha, Spain, and one travel writer tagged along to show us the region's best-kept culinary secrets.

Dave Holbrook

I watched silently as chef Eric Ripert gamely donned an aqua-green hairnet and white lab coat, and pulled ugly blue shoe covers over his black Prada sneakers. I myself had balked at the hairnet, instead stuffing my hair inside a baseball cap. He then watched carefully as a worker showed us how to remove a squishy wheel of fresh sheeps’ milk cheese from its plastic mold. In another moment, Ripert was banging the mold on its side, trying to free the soft white round so it could be dunked into a saltwater brine, and then left to age into manchego cheese, the beloved Spanish delicacy.

I had only met Ripert a few hours ago, but I was already impressed and enchanted. We had come to the Castilla-La Mancha region of Central Spain, about 60 miles south of Madrid, with 50 Best (the organizers of The World’s 50 Best Restaurants), who were working on a short documentary about the culinary delicacies of the region. We had a packed schedule of visiting various farms, food artisans, and attractions, plus three of the 11 Michelin-starred restaurants in the region.

For Ripert, the head chef and co-owner of the acclaimed, Michelin three-starred Le Bernardin restaurant in New York City, being filmed was nothing new. From three seasons of his cooking and travel show Avec Eric to appearing frequently as a guest judge on Top Chef to being a guest on countless talk shows, he was a natural. I, on the other hand, was a jet-lagged mess. Luckily though, everyone was focused on Ripert — I was just along for the food-filled ride. Here's how we spent four food-filled days in Castilla-La Mancha — and how you can, too.

Dave Holbrook

Day One

Our manchego cheese adventure was at Finca La Prudenciana, a family-owned sheep farm and creamery in Tembleque, a town of just 2,000 residents. After we successfully sent our cheese cylinders to their saltwater bath, we learned the rest of the manchego-making process, from milking the resident flock of sheep to aging for between three and 12 months. At the end, we are rewarded with a huge spread of regional delights, cooked by Maria Álvarez Sánchez-Prieto, the wife of head cheesemaker Alfonso. Together with their children, Marta and Santiago, they live on the farm that Alfonso’s parents bought in the 1950s, where they also grow almonds, pistachios, and walnuts. In addition to traditional Spanish tortillas, a roasted tomato and red pepper salad called asadillo manchego, and plenty of cheese (a favorite of Ripert’s is the one marinated in olive oil), the centerpiece of the spread is the cordero manchego. It's baby lamb that we watched Maria prepare with white wine and lemon juice and put in the oven before our tour began. To say the meat is juicy and succulent is a vast understatement; the special dish is usually reserved for holidays.

Before collapsing into our beds back in Toledo, the ancient walled capital city of Castilla-La Mancha, we catch a cotton-candy-colored sunset at the famous Consuegra windmills, which date back to the 16th century and are the setting for Miguel Cervantes’ "Don Quixote."

Day Two

Dave Holbrook

The next day begins with an early-morning visit to one of Toledo’s oldest businesses: Santo Tomé Obrador de Mazapan, which has been making marzipan on-site since 1856. This city is the birthplace of marzipan, invented by nuns as early as the 1500s. Most people either love or hate marzipan, as you will likely discover if you bring it up in conversation. I was a hater. I say “was” because I soon learned I have never had fresh marzipan, and possibly never even real marzipan, which is made from actual almonds and not almond extract. Ripert is a resolute lover. “I even love the bad stuff, even the overly sweet ones,” he laughs. “I’m the only one.”

At Santo Tomé Obrador de Mazapan, they use only fresh, locally grown marcona almonds, sugar, and honey to make 40 tons of the stuff each year. The three ingredients are run through a mill and then combined with water to form a sticky paste, before being used the next day to bake all kinds of delicious treats on well-worn wooden baking trays. After our tour of the bakery, we munch on fresh-from-the-oven marzipan treats.

Later, we leave the walled city and drive up to a dramatic stone entrance gate, with Cigarral del Ángel emblazoned on it. This was the estate of the famous poet Fina de Calderón until she died in 2010, and the expansive grounds are stunning, with views of the Tagus River and the fortified city of Toledo. In 2019, the city invited chef Iván Cerdeño to move his restaurant here. He walks out to greet us, leading us through the gate, past a manicured garden, and up to his restaurant, Restaurante Iván Cerdeño, where two hard-earned Michelin stars are displayed by the door.

It’s hard to put into words the 21-course meal Ripert and I are treated to next. Cerdeño’s inspiration comes from Toledo itself — he mines ingredients from the river and surrounding farmlands. He also devoured a 16th-century cookbook that was published in Toledo. Called the Libro de Guisados (Book of Stews) by Ruperto de Nola, it was the first Spanish language cookbook. He took several of those recipes and updated them for a modern palate. The food is inventive, with dishes like sardine stuffed with red partridge, sea urchin and almortas (grass pea) cream served inside the urchin shell, and Senador’s hare, a local wild rabbit that we caught at the end of its winter season. There is a dish made from pine and black truffle, and the sous chef comes out to shave some fresh green pinecone atop it. As I eat it, I look out onto a massive pine tree through the large picture windows. When we’re served baby eels, Ripert is visibly excited, telling me they’re a delicacy and that they cost more than $2,000 a pound in the U.S. right now.

“All the food is really delicate and refined,” Ripert says. “And very respectful to the product.” Almost as exciting as the food is the wine pairing, which includes local tipples like sherry, cider, and a white wine from 1985. After a walk around the grounds for sunset, we return for dessert made from manchego cheese and some petit fours, including a pistachio apple tart and a rosemary dark chocolate truffle.

Day Three

Dave Holbrook

This morning, we are driving to an olive oil farm in Los Navalmorales, about an hour away from Toledo. At Finca La Pontezuela, there are 18,000 trees growing five types of olives, including the rare redondilla olive. The owners tell us that they are one of two farms to grow redondillas. After seeing the olive mills and oil storage tanks, we explore the state-of-the-art interactive visitors center built in 2020, which explains everything you’d want to know about olives and olive oil. Finally, we get to taste the products. The farm produces extra virgin olive oil under the 5 Elementos name, including single varietals — everything is grown there. There’s arbequina, picual, cornicabra, hojiblanca, and the ultra-rare redondilla, which Ripert can’t wait to get into his mouth. But first, they teach us how to swirl it in the glass while covered, and then uncover it to release the heady aroma. Then, we put just a sip on our tongue, immediately swishing it to the back of our mouths as we gurgle it down. We agree the picual is the spiciest, burning the back of our throats, while the redondilla is smooth and flavorful, a perfect balance. Soon, they bring out platters of glistening strawberries and kiwis, cubes of a local queso de cabra (goat’s milk cheese), and chunks of bread, pairing each one with a specific oil. We can’t get enough.

Even though we’ve filled up on the olive-oil-drizzled-snacks, it’s somehow lunchtime again and we’re due at Raíces-Carlos Maldonado in the village of Talavera de la Reina. When we arrive at the nameless façade next to a graffitied wall, chef Carlos Maldonado greets us, and shows us his tiny kitchen, which is practically next to the door. It’s opposite a wall-length mural, featuring fantastical images of everything from UFOs to floating chili peppers. The light fixtures are decorated with white rooster and fish heads, and there is fantastically painted pottery on shelves, which we learn were designed by the staff and made by a ceramicist nearby.

Dave Holbrook

Our servers wear jackets and a single white glove, and they have a lot of piercings and tattoos, just like Maldonado himself, who shows us the tattoo on his forearm of a food truck, a nod to his first job. He also runs a school nearby for troubled youth, which he admittedly was once himself, to learn how to cook. This is a Michelin one-starred restaurant, and the tasting menu is still elaborate and full of complex techniques, but it’s also playful and fun. Ripert and I make our way through the 20-something bites, which are influenced by Maldonado’s beloved Castilla La-Mancha, as well as places like Puebla, Mexico, with dishes like local squab tacos with mole and what are essentially tequila-lime jello shots served in the mouth of a ceramic snake (really). Each dish is presented on a unique and whimsical ceramic piece, featuring everything from a giant red Michelin star to a multi-tiered tower reminiscent of a hookah to a dish featuring Maldonado’s son’s handprints. That last one holds the “pizza” course, which is actually one of the desserts, made with a meringue crust, beet sauce, and white chocolate instead of cheese.

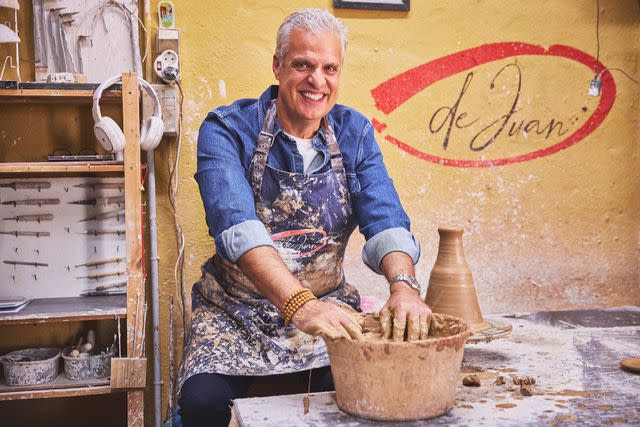

Talavera de la Reina is known for its ceramics. And one man, Fran Agudo, has become the go-to guy for custom dishes and serveware for the region’s top-tier restaurants, including Raices. When we walk into his studio De Juan Artesania, there are shelves and shelves of Agudo’s creations, and we quickly recognize some pieces from Raices and Iván Cerdeño. Agudo asks Ripert if he wants to try his hand at the wheel, which he eagerly agrees to. Ripert swears it’s his first time at a potter’s wheel, but after a brief demo, he manages to turn out a perfectly acceptable plate. Is there nothing he can’t do?

Day Four

Dave Holbrook

Our final day in Castilla-La Mancha starts leisurely. By now, I know enough to skip breakfast, especially because our first stop is a restaurant. This time, we’re going to the industrial town of Illescas. We arrive on a nondescript block, but this time, the entrance to the restaurant is clear. Ancestral is the brainchild of the young chef Victor Gonzalo Infantes, who cooked at one of the best restaurants in Madrid before deciding to return to the area where he grew up. The tiny restaurant utilizes live fire to create some of the best dishes we’ve had the entire trip. Both the food and decor are a bit more rustic here (but still stylish), with dishes like local blue duck with wild mushrooms and trout (which Infantes showed to us fresh, as it was delivered from a nearby river) with its own roe, accented with beetroot, made to look and taste like saffron. One of Ripert’s favorite dishes was a traditional stew made with pigs' ears, Castillian chickpeas, and tubers, alongside smoking crunchy pigs' ears drizzled with an adobo manchego sauce. Infantes’ talent is unmistakable, especially in simple yet delicate dishes, like tiny wild-grown cherry tomatoes in an Iberian ham soup.

The afternoon is spent back in the walled city of Toledo on a walking tour, where we visit the famous Toledo Cathedral and the old Jewish Quarter, which has two remaining synagogues that are now museums. We also manage to squeeze in some ham-and-cheese croquetas, which Ripert had been craving, insisting he couldn’t be in Spain without having one.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.