The Underground Syrian Library that Provided Respite from War and Propaganda

For Franco-Iranian journalist Delphine Minoui, what was supposed to be brief trip to Iran to reconnect with her paternal roots became a decade of living in Iran, Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, Egypt, and Syria. Today, Istanbul is her home base. “There is a saying in Istanbul: ‘They call it chaos. We call it home,’” Minoui tells ELLE.com of her attraction to the region. “I got used to this “chaos.”

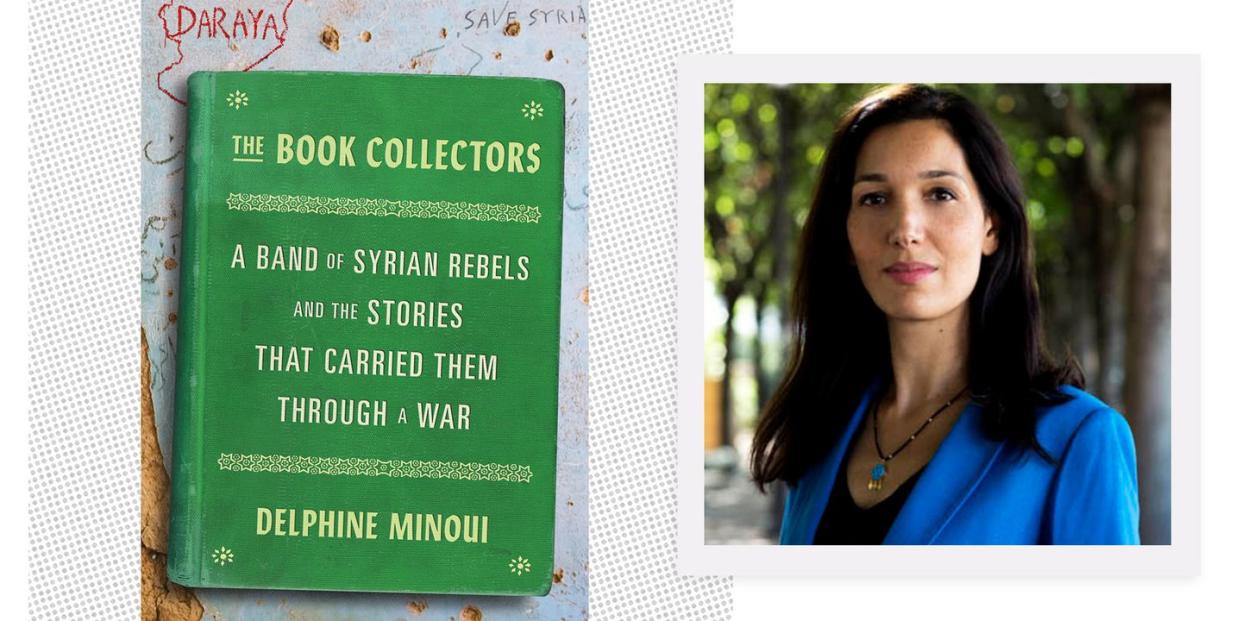

Her nonfiction book The Book Collectors: A Band Of Syrian Rebels and the Stories That Carried Them Through A War provides glimpses into the 2012–2016 siege of Daraya, a suburb of Damascus, via a secret library set up in the basement of an abandoned building. By way of video interviews and online chats with the library’s founder and patrons, Minoui chronicles how these men created a sanctuary under unthinkable circumstances. Readers’ favorite titles varied from The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho to Les Misérables by Victor Hugo to Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus by John Gray.

Published three years ago in France, The Book Collectors has been studied in French schools and was adapted as a theater play in Belgium. For its English-language release, ELLE.com spoke with Minoui via email about the transformative power of reading, the eternal relevance of Ray Bradbury, and reporting when you can't be on the ground.

Can you talk about your relationship to the Internet, and what it means to explore stories happening in a foreign territory?

As a reporter and writer who’s been working in the Middle East for more than 20 years, I’ve always been an advocate for witnessing ongoing events with my own eyes, of being out there to give voice to the voiceless. It’s part of my job and responsibility to provide a firsthand account in order to fight stereotypes and potential propaganda. But the Syrian revolution—which sadly turned quickly into a war—reached another level of danger that put us reporters in a tougher situation. From the very beginning of the 2011 uprising, the regime of Bashar al-Assad blacklisted many foreign journalists and deprived them of press visas. During the first years of war, we still managed to access rebel-controlled areas, but with the rise of Daesh, or ISIS, it became too dangerous to get there; colleagues and friends were kidnapped, some killed. Then came the dilemma: How can we make a story still “visible” when it’s becoming invisible? This question obsessed me a lot.

You found out about the library via Facebook, on the Humans of Syria page, right?

Yes. To a certain extent, Facebook, Twitter, and social media gave me at a solution by default. As the revolution had given birth to a new generation of young citizen journalists, I started relying more and more on comments, videos, and photos posted on the Internet. These posts, as well as daily exchanges with different contacts and sources on the ground via Whatsapp, opened an extraordinary window to a territory that I couldn’t access anymore. It helped me, as well as many journalists and Human Rights NGOs, to keep track of what was really going on: the systematic torture of jailed dissidents, the deliberate shelling of hospitals and civilian areas, the chemical attacks. Of course, each post had to be verified with other sources and fact-checked to avoid disinformation and potential fake news—even on the opposition side. That’s how I bumped into the Daraya library picture. To me, that picture is an amazing summary of everything: It tells the story of normal citizens hidden by war, it talks about peaceful resistance while the regime tries to portray anti-Assad activists as “terrorists,” and, from a more universal point of view, it’s a very powerful metaphor for the resilience of human beings in times of despair.

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury is mentioned, and it's a chillingly resonant reference. How much had you covered censorship before this story, and how does it compare to other ways you’ve tackled this topic?

Books have often been the first target of dictatorships, as they are the best means for education and enlightenment. Daraya is sadly one among so many other examples. Under Daesh, the famous library of Mosul University in Iraq, which I visited, was partially destroyed and burnt by ISIS members between 2016 and 2018. Also, I will never forget those days in Iran when, at the end of the ‘90s, we used to wake up with the news of an intellectual or writer being murdered. One of them, whom I knew, was Mohammad Jafar Poyandeh. He had translated the Declaration of Human Rights into Farsi and was known for fighting censorship.

But it is also in those times of darkness that writers and artists find solace in fighting censorship with more creativity, like the young librarians of Daraya who not only save books from the rubble and build up an underground library, but also create a magazine and draw joyful murals on the destroyed walls of the city.

The book touches on both urgency and escapism. As a writer, how did you try to balance these two very different extremes?

During the writing process of the book, as I could not access to Daraya, I found myself torn between the temptation of turning this story into a novel (especially during those moments when I lost contact with them) and sticking to the reality. I ended up sticking to the reality, which meant also sharing my doubts and interrogations with the readers, for them to understand the fragility of such a process, but also the necessity of listening to unapproachable voices coming from a besieged city.

It was not an easy exercise. Through our conversations, I discovered that the library gradually turned into a sort of underground university. It became an open debate space, where chairs were sometimes pushed aside for dancing, where funerals were held, where slogans were invented while guns relentlessly fired above. I was never able to visit them—Daraya was completely surrounded by the regime’s army—but thanks to the Internet, I created a special bond. Amid bombs and power cuts, I listened to and wrote down their stories.

You quote activist Mazen Darwish at the outset: “There is no jail that can imprison the free word, nor is there a siege tight enough that can prevent the spread of information.” But there’s also a very poignant line: “What’s the point of saving books when you can’t even save lives?” Can you discuss this tension: How we need the symbolism of stories and cherish the materiality of books, but also, they can only deliver so much when safety is at stake?

Books cannot prevent bombs from dropping, they cannot stop the bullets from falling. But to a certain extent, they can save lives. Books have this power of helping people to stay human, to cultivate hope. For those Daraya guys, saving books meant saving their heritage, preserving a few traces, however minute, of their past and their cultural identity that were getting erased under the daily effect of bombs. It meant resisting the regime, along with its ideology and propaganda. One of the principles for their secret library involved writing the owners’ name into the first page of each book, in the hope of giving it back once the war was over. Much to my surprise, I also discovered that their library had precise rules: opening hours, return dates to be respected. They said it was a way to keep a sense of life and normality and routine in the chaos of their everyday lives. They read to stay human, to not succumb to madness. They read to escape. To continue learning. Reading was their weapon.

One man relayed to you that: “Most of the readers are like me. They never liked books before the war.” Can you expand on how you saw this readership transformation evolve?

Before the uprising, books were seen as a propaganda tool. The books that were available (and tolerated by the regime) were carrying one ideology, one way of thinking. So many books were censored. Those young people had no taste for such books. Among the books they saved were forbidden political volumes and novels (whose owners had kept them secretly in their houses). Thanks to the Daraya underground library, they had access to a huge diversity of books. It was unprecedented. As they started reading those books, they started getting access to many different ideas.

Overall, this is a very male narrative. Did women factor in at all?

Women are not very “visible” in the book. Not because they were not active, but because they were stuck in the building basements (and not connected to the Internet) for security reasons. Mostly men went outside, including going to the library, and bringing books back to their mothers, sisters, daughters. Without access to them via [the] Internet, I was not able to talk directly with them. But I want to emphasize how brave some women were: improvising schools in the building basements, or helping to take care of the injured citizens in the field hospitals.

What was your goal in writing this book? Did you want to bear witness? Provide visibility? Express hope against hope? Something else entirely?

My aim was to try to immortalize this unique experience of democracy and resistance through books and cultural means. I wanted my book to be a bridge between those Daraya activists and the world they could not access. A way to remember what happened in Syria and how peaceful activists never gave up on their democratic goals despite the violence. The library is one of the many projects they developed during the four-year siege. If I decided to focus mostly on the library, I also intended to give a picture of daily life in a besieged city and the extraordinary creativity of its ordinary citizens. How they learned to grow vegetables to counter the food shortages. How they melted plastic to make fuel. One day, they decided to build a soccer goal pitch where shells had fallen the day before. I was struck by their resilience, by the collective solidarity they never ceased to believe in. For four years, they braved explosions, the cold, power cuts, the lack of running water. Dignity and creativity became their shield against barbarity.

You Might Also Like