UFLPA: What Insiders Say About Forced-Labor Law’s First 8 Months

It’s been eight months since the United States put into effect a far-reaching law aimed at cracking down on forced labor in China. So is it working as designed? The answer depends on whom you ask.

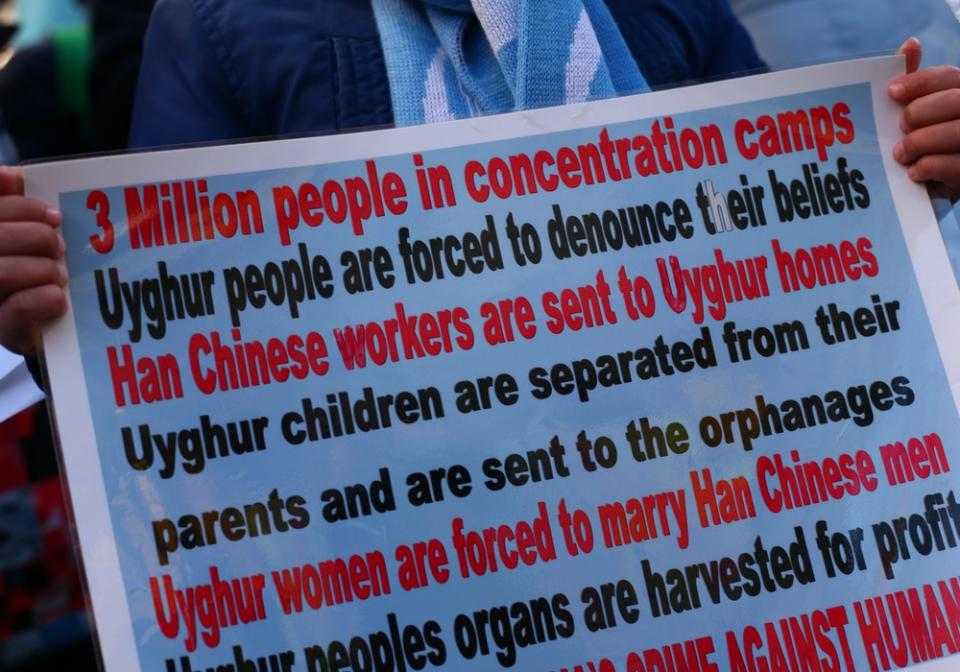

Certainly, no one denies that the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, or UFLPA, serves a vital function: preventing firms from knowingly—or even unknowingly—trafficking into the country goods made under coercion by Uyghur and other Turkic Muslim minorities, particularly those in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, where Chinese authorities have unleashed a campaign of persecution that many have labeled genocide. By imposing a “rebuttable presumption” that all goods made in whole or in part in Xinjiang are tainted with modern slavery and therefore barred unless “clear and convincing” evidence proves otherwise, lawmakers meant to take a stand against the atrocities and persuade China to end its repressive policies.

More from Sourcing Journal

UFLPA Needs to 'Aggressively Step Up' Enforcement, Lawmakers Say

Civil Unrest and Political Risks Could Undermine 'Friendshoring' Movement

“The whole point of the UFLPA is just to essentially force companies to redirect their sourcing out of a region that is using systematic forced labor as part of a campaign of crimes against humanity,” said Allison Gill, forced labor director at the Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. “We have a moral obligation to take action to try to stop what is an ongoing human rights crisis of which forced labor is a core component. So the idea is to change that behavior.”

Have questions about Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act or #UFLPA enforcement? We’ve posted updated UFLPA FAQs and other new resources on our website. To learn more, visit our website at https://t.co/FOUyvudTlf pic.twitter.com/qU4kwh5IXG

— CBP Office of Trade (@CBPTradeGov) February 23, 2023

Another goal, she added, is compliance with U.S. law, which has outlawed the import of forced labor goods, no matter their origin, since the establishment of the 1930 Tariff Act. Until recently, the prohibition has been weakly enforced, in part because of a since-closed “consumptive demand” loophole, which exempted such goods if the United States couldn’t produce them in sufficient quantities to meet consumer needs.

In terms of blocking goods, the UFLPA appears to be a ringing success. Between June 2022 and January 2023, Customs and Border Protection—CBP for short—flagged roughly 2,700 shipments, valued at more than $814 million, for potentially violating the terms of the statute. Of these, one-sixth were categorized as apparel products. And for good reason: Cotton is a booming business in Xinjiang, which produces more than 90 percent of China’s total, possibly by dragooning more than half a million Uyghurs to pick cotton by hand through a state-sponsored labor transfer and “poverty alleviation” scheme. In turn, Chinese cotton makes up some 25 percent of the world’s supply of the fiber.

Exports from Xinjiang to the United States, even by Chinese customs’ own admission, have been falling precipitously, even as they have increased everywhere else, including the European Union, which is putting the finishing touches on its own forced labor ban, albeit one that doesn’t explicitly target the province.

According to Dr. Sheng Lu, assistant professor of fashion and apparel studies at the University of Delaware, Xinjiang exported nearly $6.4 billion worth of garments and textile-containing accessories in 2022, up 81 percent from the year before.

Glad The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) finally implemented.I was an importer for many years. It is vital that US companies NOT be part of the problem, and our duty to be part of a solution. Yes, even if it co$t$. Willful ignorance is complicity. #UyghurLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/kd9HoCZ29r

— Jeanne DeMund (@jcdemund) February 21, 2023

The UFLPA, said Richard Mojica, who leads law firm Miller & Chevalier’s customs and import trade group, has motivated companies—predominantly those related to textiles and solar, both targets of the law, in addition to the Withhold Release Orders that preceded it—to “elevate” Chinese forced labor as a top compliance issue.

“That has prompted companies to conduct additional diligence on mapping their supply chains, conducting first-, second-level reviews of suppliers and so on,” he said. “In some cases, it has also prompted companies to reshuffle their supply chains and move away from certain supplier relationships [or] entirely from China. And so, if you view it from that perspective, I think the UFLPA has certainly been a very powerful tool to affect change.”

Still, amid this backlash Beijing has remained defiant, decrying the forced labor narrative as the “lie of the century.” It plans to double down on Xinjiang’s textile industry through the construction of up to five new industrial parks, creating 450,000 jobs. When Better Cotton, the world’s largest sustainable cotton initiative, pulled out of all field-level activities in Xinjiang in 2020, China created its own homegrown standard as a direct rebuke.

Nate Herman, senior vice president of policy at the American Apparel & Footwear Association, a trade group that represents heavy hitters like Adidas, Gap Inc., J.Crew Group and, more recently, Shein, agrees that the law has been able to prevent goods that have a “nexus” with Xinjiang from hitting the American market. Whether it has shifted China’s rhetoric, however, is another matter.

In this alert, our International Trade team discusses new rules in the US, the EU, and Germany requiring enhanced due diligence in supply chains, targeting human rights and environmental issues. Read it here: https://t.co/va2pOqk7UG#UFLPA #CSDD #LkSG #ESG

— White & Case LLP (@WhiteCase) February 27, 2023

“The goal of the ULFPA was to end the oppression against Uyghurs in Xinjiang,” Herman said. “That hasn’t happened and I don’t think it’s moved forward the ball on that.”

One grouse often repeated by importers is the lack of transparency over whose goods are stopped and what triggers a discharge. Approximately one-third of shipments flagged for inspection end up being released, a customs official said, though this was news to Herman, who said that “actual enforcement statistics” are in short supply beyond occasional operational updates. The “definitive process” he thought would materialize hasn’t happened.

“Even today, importers [will tell us] that a shipment is detained because of the UFLPA,” he said. “They are not told why it was detained or which part of the shipment was [in violation] of the UFLPA. They don’t know if it’s the supplier, the country, the type of products—they don’t know anything.”

In a way, CBP is “creating more work for itself” because if an importer petitions to get a shipment released it will have to prove that there’s no nexus to Xinjiang or a firm on the Entity List for every single product in that shipment, Herman said.

Cotton for apparel companies is still largely sourced in China.

CBP is ramping up enforcement this year of the UFLPA. Lot of cotton still coming from China.— Kyle Decentral🌱 (@KyleLogiks) February 19, 2023

“So when they submit the petition, they are submitting hundreds, if not thousands of documents, all translated into English, and then CBP has to go through all those documents,” he said. “And so that takes time, anywhere from six to eight weeks. And in our industry, when you’re talking about seasonal products, six to eight weeks could render a shipment worthless.”

Mojica understands why importers would be confused—and perturbed. “If you look at it from the company perspective, especially a company that has a robust, responsible sourcing program and would jump at the opportunity to address any issues in the supply chain, those companies have been very frustrated when merchandise is detained,” he said.

“The idea of not knowing how to fix the issue, and what to look for in building compliance programs and vetting suppliers is something that is causing a lot of concern,” he added. “Because it has been practically hard to operationalize some of the programs, especially a program where supply chains run through China.”

Are you concerned with your brand's #UFLPA compliance? Book a meeting now to connect with us at the AAFA Executive Summit, March 1-3 in Washington D.C. to discuss how TrusTrace can help demonstrate due diligence and conduct effective supply chain tracing.#supplychaintransparency

— TrusTrace (@TrusTrace) February 22, 2023

Civil society groups would like more trade information to be made public, said Gill, adding that organizations like hers are “quite interested” in finding out what evidence CBP finds compelling “to the extent that they can share that.” Transparency, she said, is really “key” to more effective enforcement. It’s also an important step to ensuring more global alignment on import bans—the United States cannot tackle forced labor that “really infects” a commodity or an entire region of production alone. Neighboring allies like Canada and Mexico—both of which have banned forced labor products in line with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement—are particularly important in casting a tighter net, Gill noted.

A customs official said that CBP, as the largest law enforcement agency in the country, is bound by some restrictions regarding the information it’s able to share, whether it’s because of trade secrets or to maintain business confidentiality. It tries to take a risk-based approach, he said, one that makes sure it’s the “least disruptive” to lawful trade while also “being very responsive” to issues of forced labor.

“We can’t say, ‘don’t source from this specific company,’” he said. “We can’t tell companies who to do business with; companies need to be able to make those decisions independently.” Not that CBP isn’t aware of the criticisms about its perceived opacity. On Thursday, the agency released a fresh tranche of guidance, which it said was “in response to industry’s requests for additional resources” to comply with the statute. These include revised frequently asked questions, best practices for applicability reviews and advice on document submissions.

There are things CBP would prefer to play close to its chest, however. The customs official likens it to speed traps on the highway—“We can’t specifically say, on this day, we’re going to set up a speed trap right here because then [people will just get around it],” he said. “But we don’t leverage any super secret information. There’s no classified intelligence that comes in that gives us information on supply chains at risk. Everything is open source. Everything has been relatively in the public sphere.”

Still, the fact that barely anyone has tried to rebut the rebuttable presumption to date shows that the UFLPA, as the “most influential piece of trade legislation in years,” wasn’t conceived or drafted as such, said John Foote, a partner in law firm Kelley Drye & Warren’s international trade practice group. This has resulted in a “lot of important issues and questions that are unresolved by the UFLPA,” he said.

“Every other entry that is being detained under the UFLPA is being resolved on a basis that is being worked out by customs on its own, not with the guidance of statute,” Foote said. “In other words, all those applicability reviews. Now that’s not inherently problematic, per se. But it is an indication that the law wasn’t written with an understanding of the guesswork associated with identifying merchandise that could be subject to the presumption.”

The customs official said that things have gotten a bit “twisted.” Ultimately what CBP aims to do is follow its normal regulations and allow importers due process.

“Most of the time, importers are saying, ‘Well, I manufacture this in Malaysia; there is nothing tied to the Xinjiang region,’” he said. “But we know that Malaysia is a major transshipment point; a lot of inputs in China are going into Malaysia for downstream manufacturing. So that in itself, because of the ‘whole or in part’ piece can make that shipment subject to the UFLPA.”

🚨 #SupplyChain Compliance Alert. Get the latest on #UFLPA in our risk center: https://t.co/n1kjcZj6i4, watch our webinar https://t.co/nOwUsiinvK, and learn how we're helping clients monitor risk that impacts compliance: https://t.co/GDZ5OXxwwk pic.twitter.com/FheKKrcm3o

— Everstream Analytics (@EverstreamAI) February 23, 2023

Even so, Foote argues that the Tariff Act is nearly a century old and has never “substantially evolved, let alone properly modernized” beyond the consumptive demand provision. While CBP has gotten “most of the big pieces” of what is a considerable challenge, he said, there’s “never been a serious policy discussion about the idea of a forced labor import ban, how it should be constructed [and] what its aims should be, let alone any sort of structure for all of the different factual and legal determinations that go into the multi-step process.”

Kim Glas, president and CEO of the National Council of Textile Organizations, representing American textile businesses, for one, hopes to see more detentions. She’s likely to get her wish. CBP received $101 million in fiscal year 2023 funding—a 108 percent increase over fiscal year 2022 levels. This will help pay for an additional 300 UFLPA-enforcing positions.

“Part of our strong concern with our current de minimis trade structure is that it allows e-commerce products to come to our doorstep with such little scrutiny duty-free, can circumvent Section 301 tariffs and can contain Xinjiang cotton,” said Glas, referring to shipments that skirt import taxes because they fall under the $800 threshold. “So what are we doing about those billion shipments that we’re seeing a year coming to the United States—and about half of those are textiles and apparel? And then in addition, what are all the activities that CBP has undertaken that really target the monumental impact forced labor has on the supply chain?”

Translation: CBP and Vietnamese Customs talked about how Vietnam can help halt US imports of goods made with #Uyghur forced labor. UFLPA enforcement isn't easing up. Companies would be really start to rethink supply chain due diligence. Now. https://t.co/gyHOmtk38H

— NomoGaia (@NomoGaia) February 24, 2023

Businesses should be seeing stopped containers off the port of L.A. on a “pretty regular basis,” she said, estimating that CBP is likely targeting between 30 to 40 percent of trade. There’s more room, to wit, for more effective enforcement.

“I think CBP has a very difficult job; Congress is basically saying, ‘We’re going to give you the resources to do that by hiring more officials and by having various testing technology available to you,’ but I would say it’s not going quickly enough,” Glas said. “I mean, clearly, these issues are still pervasive. Unfortunately, there are still horrific reports coming out of Xinjiang, and we need to be doing everything possible publicly and visibly showing the world that these supply chains are illegal.”