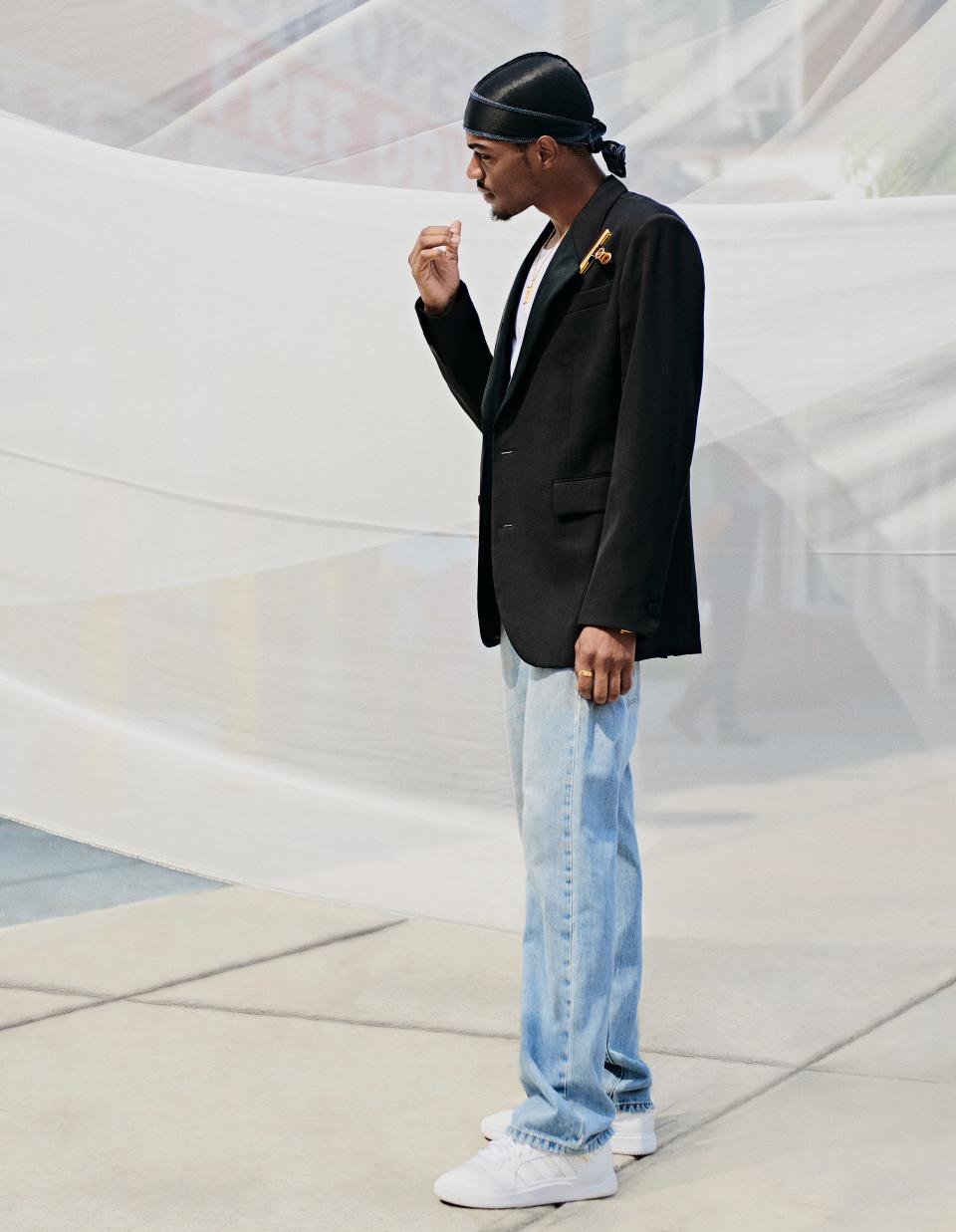

Tyshawn Jones, Supreme Being

He is the king of New York, but you know what they say: Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown. For the skater Tyshawn Jones, that uneasiness may be straight-up ambivalence or potentially a monster case of modesty. “You've got to always think you're the worst,” Jones says, “so that you can push yourself to be the best.”

There are plenty in the skate community who say that Jones is the greatest athlete the sport has ever seen; the king plugs his ears. He's done things that nobody has ever seen, but he's eager to do more. He bucks convention, avoiding the popular spots and the trendy tricks. “I do whatever I want to do,” says Jones, fully aware that he's obsessively watched—studied, even. “Shit, I'm a leader in my eyes,” the king says.

Jones's kingdom is made up of craggy sidewalks, subway entrances, passing construction vehicles, and imposing trash cans. The standard New York City trash can—a heavy-bottomed latticework of forest green metal—is a curious thing on which to build a reputation, but that is what Jones has done.

That the receptacle is a crucial proving ground is itself a weird idiosyncrasy of the New York skating scene. But the can, 29 inches tall and 21 inches wide, is critical to understanding Jones's greatness. For most skaters, vaulting over a single one is a cause for celebration. Jones is able to line up four in a row, Evil Knievel-style, and clear them all.

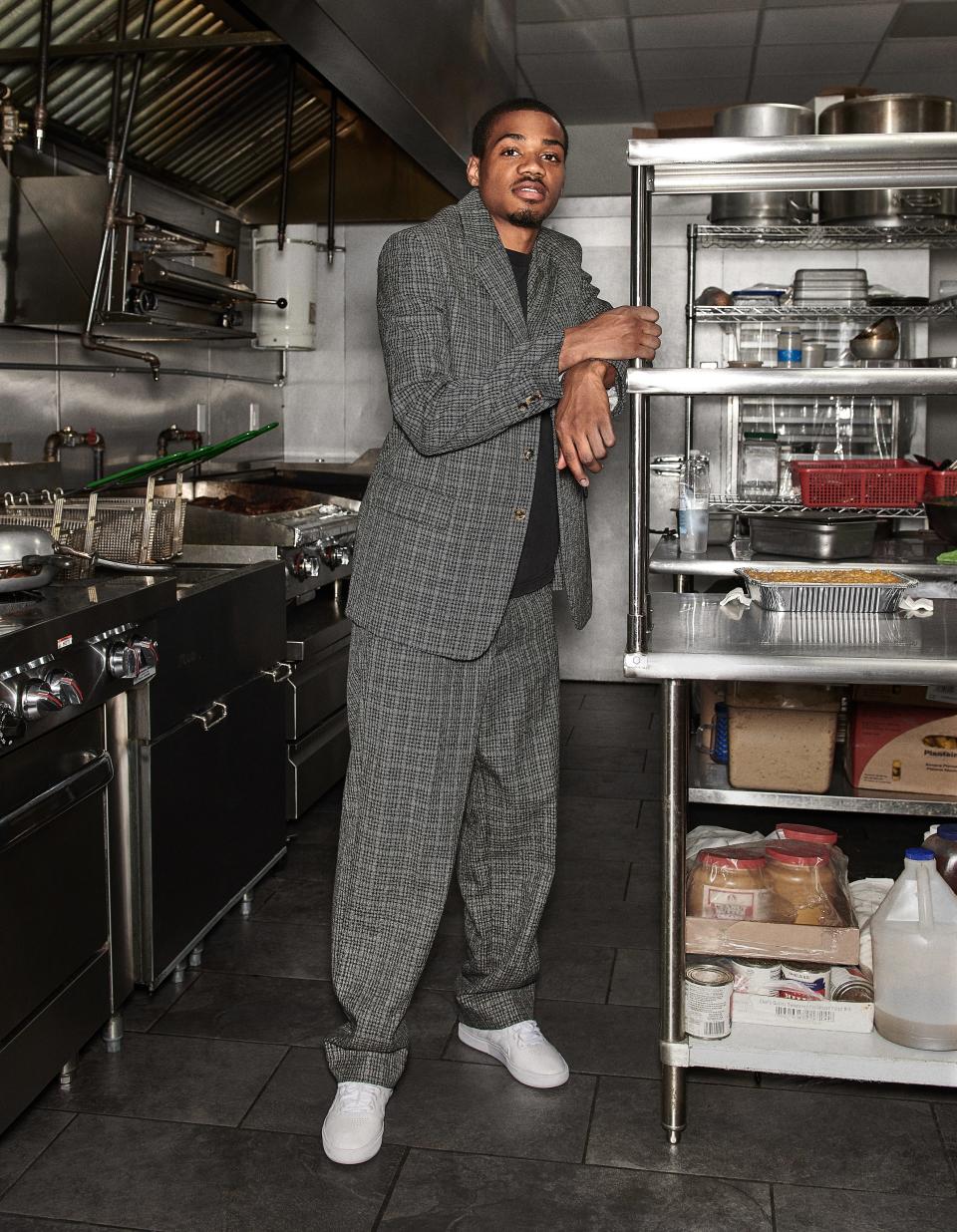

At 20, he's already ticked off every box on the Great Skater checklist: The requisite sponsorship deals with brands like Adidas, Supreme, and Fucking Awesome, plus 2018 Skater of the Year honors from the skate bible Thrasher. Then some atypical accomplishments, like the Bronx restaurant he owns—it's called Taste So Good (Make You Wanna Slap Yo Mama)—or his line of nuts and bolts called Hardies Hardware, which doubles as a burgeoning clothing brand. More projects outside skating, none of which he'll tell me about, are on the way. “I'm trying to be the richest skater that's ever lived,” Jones says.

We've met at the restaurant. He's wearing a do-rag, cream white with a sherbet-orange hem. His regal garb, all black: sweat shorts and a hoodie that he keeps pulled all the way over his forehead. Despite all that he's accomplished, he is pathologically humble when it comes to talking about his ability—preferring to sink his head into his hands and offer a quiet “Thanks.” Still, he understands the unprecedented nature of what he can do on a board. “How I see it is: What if this basketball player came in and just made a bunch of half-court shots every game? And he won MVP,” Jones says, referring to his raw ability to do what no skater before ever could. “The industry would be pissed: ‘He's a Harlem Globetrotter. Fuck that.’ ” Jones says there's a standard recipe for skater greatness, but he has a freakish quality that allows him to work outside those guidelines. An approach to skating that is not typically seen because, well, most people simply can't replicate it.

Comparing his innovations to half-court shots is a good indicator of how Jones feels about what he's pulling off—tricks so absurd that you don't even have to know anything about the technical side of skating for them to blow your mind. “He does the unthinkable, the unbelievable, and shows you that it's possible,” Na-Kel Smith, fellow Adidas team rider and Mid90s star, tells me via email. “When you see it on video, it's like, ‘What the fuck?’ ”

“Skateboarding, that's impossible to master. So that's why I like it.”

Whenever an athlete accomplishes the impossible, video games are evoked: the basketball player who is on fire, the scoreboard-wrecking quarterback whose exploits seem feasible only inside Madden simulations. Fittingly, video games shaped Jones's idea of what could be done on a skateboard. At 10, he spent the summer sitting around his New Jersey home, spending his days with his brother and his uncle, who is the same age as he is, playing the hyper-real game Skate. “Yo,” his mom said to them one day, according to Jones, “you always stay in the house and play video games. Why don't you all go outside?”

With $40 each from Mom, the group went to Target and bought skateboards. Even for a future phenom, skating was punishingly difficult at first. He watched as his uncle and his brother sped home, but he couldn't even push. So he walked, board in hand, from the store back to the house. Jones estimates now that it took him a few months to get anywhere on a skateboard. He stuck with it only to be like his elder brother, but once he broke through the steep learning curve, he fell in love.

Soon thereafter, Jones and his mom moved back to the Bronx, where they'd lived before Jersey. Suddenly he felt isolated from everything but his board. “I had no friends, so I just skated every day,” he says. “Every day, every day, that's all I would do. I would just practice.” Going to skate parks exposed Jones to kids who were better than he was. He didn't like that. “It was a competition to me,” Jones says. “I was like, ‘Hell no. These niggas is good. I have got to get good too.’ ”

A kid he met at the skate park introduced him to the idea that skaters could be sponsored—but told him he'd never earn a deal by filming his tricks there. “From early on, I knew that was forbidden,” he says. So Jones started his conquest of New York—making use of the city's handrails and staircases. It wasn't entirely about exposure, though; there was a pragmatic reason for chasing a sponsorship: “Buying boards and shit was expensive.”

Almost a decade later, what makes Jones such a special skater is his athletic talent—his ability to easily do what Smith calls “unthinkable.” He played other sports growing up but thought they weren't challenging enough. He guesses he could have gone to school for hoops, but “basketball is too wack to me,” he says. “I hated running up and down the court.” Not because he'd get winded but because it was too easy and too predictable.

“LeBron James, when he plays basketball, you know what you're going to see: A crazy dunk or a shot go in, and it's the same shit every day,” he says. Basketball legends are made only by tallying up more of the same—points, rebounds, championships, whatever; skateboarding is about relentlessly tearing off the shrink-wrap, maniacally burrowing for newness. When Jones lands a trick or conquers a certain spot, he moves on to something even more challenging. One trash can becomes two, and two become four. It's like if James, after wiping out the Golden State Warriors, summoned a group of basketball-playing aliens just to keep upping the difficulty level for himself.

“Skateboarding, that's impossible to master,” Jones says. The impossibility, for him, is exactly the point: “So that's why I like it. I feel like I can always push myself and learn something new.”

Doing the new and unfathomable has been a Jones specialty since early on. When he was only 13, Jones was out shooting video with Supreme skate videographer William Strobeck. An able cameraman is an essential tool for any skater with aspirations of making history. Skaters become legendary by compiling the best footage, often in videos cut with peers. Jones thinks about these videos like albums, a giant posse cut. He has the tendency to make others look as foolish as Nicki Minaj does on “Monster” or Kendrick Lamar on “Control.”

Strobeck and Jones were at the New York County Supreme Court in downtown Manhattan, a granite Roman-style colossus that seems to have been constructed to bait skaters. It features a massive staircase, lined on each side by a ledge that offers the daring a five-foot drop into a slick sloped bank that shoots riders into a second, six-foot drop. Navigating the entire setup is nearly impossible. New York's preeminent skating website, Quartersnacks, declares of the spot: “Don't bother… You weren't going pro anyway :).”

Strobeck watched a teenage Jones do battle with the courthouse. Over the course of two years and 200 visits to the site, Jones landed five tricks. Once, after leaving a session at the courthouse and descending a staircase past the NYPD headquarters, Strobeck found himself gazing at the handrail. “The best skateboarders have walked down these stairs and looked at this rail, and no one's grinded it,” Strobeck says. “I go, ‘If you grind this rail, you're gonna make history.’ ”

During their first day trying, Jones and Strobeck were kicked out. Jones's efforts on their return visit are documented in the Supreme skate video “cherry.” There's baby-faced Jones riding the rail down the staircase. He lands it and hops off his skateboard before ricocheting off a metal fence. For a victory lap, he runs back up the stairs and pulls off his shirt.

“He was like, ‘I fucking did it,’ ” Strobeck says. “Tyshawn is like that: I fucking did this. He wants to make a statement. Ever since then, he's never wanted to look secondary in a video.”

“If they told me, ‘Come to the Olympics,’ I'd be like, ‘All right.’ But I'm not about to go try to qualify.”

Seen through the eyes of a skater, any everyday object or location can be transformed into something significant. For instance, a subway entrance—an ordinary urban fixture used by countless New Yorkers every day—could be reconstituted as a setting for glory by the skater brave enough to ollie over it.

When Strobeck looked one day at the 33rd Street subway-station entrance, he saw a treacherous chasm and visualized Jones clearing it. Strobeck saw how it could be done: Jones would start at the raised office plaza at the corner of the chaotic intersection—avoiding the foot traffic going in and out of the TD Bank—and, with the right amount of speed, jump over the stone ledge containing the courtyard and clear over the subway entrance, beyond a stretch of sidewalk, into the street. Below him, an eight-foot drop to a flight of stairs. In the background, an ad for the Netflix movie Alex Strangelove. In front of him, on the other side of the gap, a nearly five-foot-high railing, barbed menacingly with spikes. “It's super dangerous,” Strobeck says.

Skating is nominally an individual sport, but greatness typically requires a group effort. Strobeck got the idea to jump the subway entrance from Ben Kadow, one of Jones's Supreme teammates, who gave Jones his blessing to try it. Jones attempted to fling himself over the entrance almost 20 times the first day. He could get over it but wasn't able to land on his board. A buddy kept the subway stairs clear of passersby, lest a commuter catch an errant board in the face. Meanwhile, an impromptu security force formed when a group of bikers saw what Jones was trying to do. They stood on the street corner and created a barricade to halt traffic for Jones. On one attempt, he didn't have the air and badly bruised his heel.

Jones returned a few days later with an even larger crew of photographers. He made four or five more jumps without landing the trick. There were endless obstacles: rubbernecking tourists, cars whizzing past, irritated New Yorkers trying to emerge from the subway. Every failed attempt, every piece of proof this was impossible, only made Jones want it more. “In his head he's like, ‘If I don't do this, it's going to fucking drive me crazy,’ ” Strobeck says. That final day there were three or four more failed attempts. And then magic. He committed: Jones snapped—“Fucking ollied,” Strobeck says—shot over the subway entrance, and landed on the other side. “We. Got. That,” Strobeck remembers thinking, pausing dramatically between each word now.

Even after Jones eventually landed the trick, he remained stoic. He offered a hand and maybe a grin. “I didn't even want to skate it,” Jones says. “But I was just like, ‘Fuck it,’ and it winded up happening.”

An image of the feat appeared on the cover of Thrasher in January, Jones streaking above the subway entrance. In the background are onlookers with hands over their mouths or phones held up to capture the stunt.

For all the athleticism skating requires, it's just as much art as sport. Like painting, but you can die. Jumping clear over a subway entrance is death-defying and cool and awe-inspiring and impossible-until-it-wasn't and fucking insane, but what's great, Strobeck argues, what makes it cover-worthy, is…the bigger picture. “It's the 6 train, and that's the train that he took as a kid [from the Bronx],” Strobeck says. “There's a story!”

Jones, tearing into a plate of fried shrimp and halibut made by his mom, who was at the restaurant that morning and runs the place, claims to be less preoccupied with his legacy. For Tyshawn Jones, conquering spots and landing unprecedented tricks are just things he does during his day-to-day. He claims not to register these achievements for what they are: individual puzzle pieces that when put together create an image he can point to as proof of his all-time greatness. Jones says most of that strategizing is Strobeck's doing: “He's like, ‘No, it's an art. You've got to think about that.’ ”

That type of thinking is important in skating, which, unlike nearly every other sport, lacks any statistics to measure greatness. There are tournaments, but they are largely considered lame. Skateboarding will make its Olympic debut at the 2020 Summer Games in Tokyo. Jones won't be on the team, but the draw of winning a gold medal—a tangible prize to hold up as proof of supremeness—might coax him into competing someday. “If they told me, ‘Come to the Olympics,’ I'd be like, ‘All right,’ ” Jones says of competing in the most prestigious athletic contest there is. “But I'm not about to go try to qualify. I don't like contests, anyway.” He wouldn't mind taking home a medal, though. “That'd be dope,” he says. “Hell yeah.” For the most part, the only prize anyone puts any real stock into is Skater of the Year.

The ability to jump a subway entrance is part of what makes a skater good, but what makes them great is a mélange of the intangible: style, swagger, and the story. It's not just about doing the impossible. It's about looking cool while doing so.

So Jones skates trash cans, New York courthouses, and subway entrances and is currently mastering a section of railing outside Madison Square Garden, because that, too, tells a great story: King of New York.

In Tyshawn Jones's approximation, the Fourth of July was “a good day.” Becoming the greatest skater ever requires a couple of those. Jones and Strobeck spent the summer of 2017 waking up at 4:45 a.m. to hit spots before security pulled up. No day was more fruitful than Independence Day, a real-life American superhero living up to the mythos of the holiday.

Jones was landing everything. “Dude,” Strobeck said to him that afternoon, “you're fucking on fire.” They were making their way downtown and decided to carry that momentum to the courthouse.

Strobeck had the idea to take an already iconic skating spot and up the difficulty by putting a trash can in front of the courthouse ledge. Jumping a can is a major trick. Dropping off the courthouse is a major trick. There is no good equivalent for combining them. It took Jones only a half-dozen tries to nail it.

Jones says he doesn't feel competitive with other skaters. He doesn't even watch others' videos. The only person he feels competitive with, he claims, is himself. It explains his passion for skateboarding: In basketball, football, or another team sport, the sliding scale of difficulty tilts only when players are faced with stiffer competition. You're doing the same thing over and over and over again, only the person you're doing it against changes. In skateboarding, Jones competes only against himself—what he did five years ago, the year before, yesterday.

“Do I want to be better? Of course,” Jones says. “I always want to top myself.” A half-decade ago he conquered the courthouse. Now, naturally, he needs a can in front of it to maintain interest.

Strobeck compares Jones to Jordan, as in Michael. Na-Kel Smith describes him as “the greatest to ever do it.” Mark Gonzales, a street-skating pioneer and Jones's Adidas teammate says, “Tyshawn's approach is like many others that are in the Skateboarding Hall of Fame.”

Jones doesn't want to hear it. “You can't believe you're great, too,” he explains. “If people be thinking you're great, you're going to just start thinking you're great.”

But what's wrong with that? With believing you're great?

“I feel like, if I believed I was great, I could just put my hands up in the air and say, ‘I'm already there. I did it already,’ ” he tells me. “Instead, I say, ‘That was cool—it happened.’ Gives me a chance to do it again, to do it better.”

Maybe Jones will continue to tell himself he's the worst. It is natural, after all, to trash-talk the competition—and he has only himself to beat.

Cam Wolf is a GQ staff writer.

A version of this story appears in the Fall 2019 issue of GQ Style with the title “Supreme Being.”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Jake Jones

Styled by Matthew Henson

Grooming by Rachel Leidig

Originally Appeared on GQ