The Two Types of Travelers

In Noël Coward’s 1930 play Private Lives, the wayward couple Amanda and Elyot, newly married to new people though still in love with each other, meet by chance on a French hotel balcony.

“What have you been doing lately?” she asks him.

“Travelling about. I went round the world, you know,” he replies.

“How was it?” she demands.

“The world? Oh, highly enjoyable.”

“How was the Taj Mahal?” she goes on, referring to what must have been the most familiar exotic “icon” of a British education. “It didn’t look like a biscuit box, did it? I’ve always felt it might.”

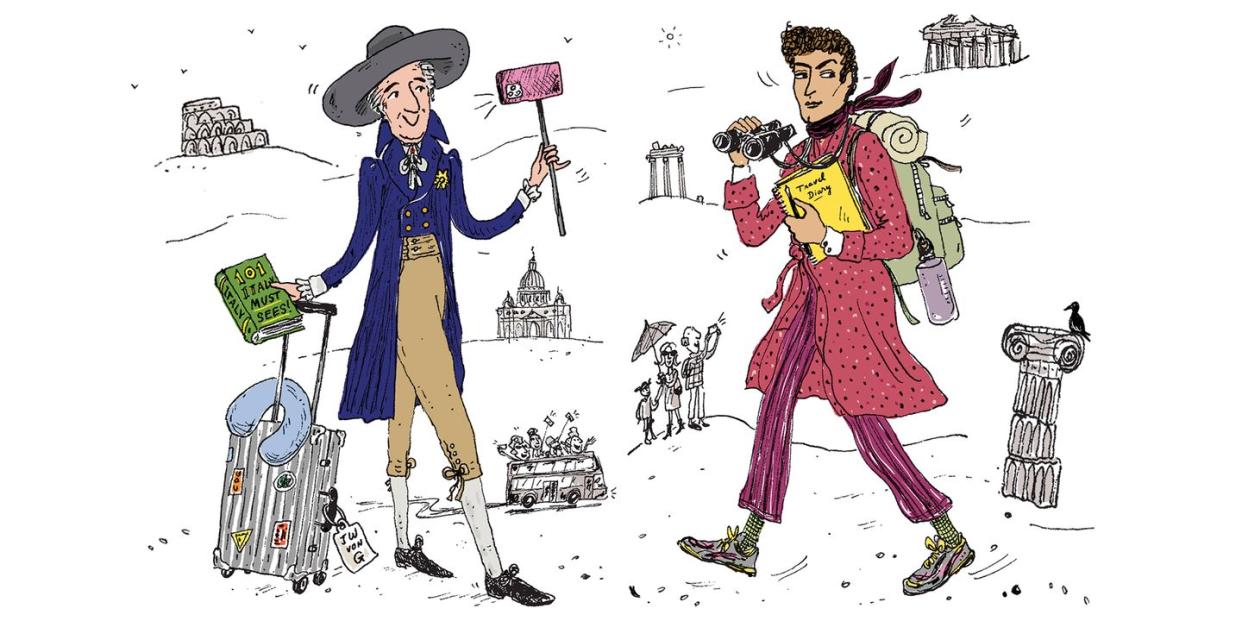

Though the subtext of the lines is about desire, with the patter meant to deflect their quickly awakening old attraction, the question is real. Why do we travel about? The standard answer is that we travel to learn, to explore, to become new people, people we weren’t before. But a corollary of the Taj Mahal Temptation is the Biscuit Box Double Bind: that we travel just as often—some of us do, at least—to confirm, or disconfirm, pictures that we already hold in our heads, developed through reading and looking long before we left. There are, I wrote once, two kinds of traveler: those who go with an image in their heads to see if they can realize it, and those who go to see what they haven’t seen before. Travelers of the former kind do not go to see the Taj Mahal or the Eiffel Tower or the Tibetan peaks so much as to test them—not primly or from a superior pose, but against their own expectations, longings, and desires. Will it look like a biscuit box? We cannot help but ask, and worry.

I have been tried, and found guilty, I fear, of being that first, image-seeking kind of traveler par excellence, or, rather, par damnation. I go, I’m told by censorious readers (you can find them among the Amazon commentators, not that I look), only in the light of things read and seen, my experience colored by a lens of expectation. I am accustomed to being, if not damned, then at least slightly cursed for this. In Paris I see the Paris I want to see, rather than some other, newer more polyglot Paris, assumed to be more actual. Our Paris, travelers like me are told, chidingly, is made of old French movies—The Red Balloon and the like—and well-remembered lyrics from songwriter Charles Trenet, intermingled with the unavoidable actuality of gray days and violet skies. Our New York is a sound-and-light collage of the opening of Gershwin’s Concerto in F and the cockatoo-bright “cathedral” paintings of Florine Stettheimer, interspersed with the black-and-white, film noir photography of Louis Stettner and the New York School. Cities become for us montages of our own invention.

Nor is this practice true only of cities, densely packed comets that trail unmissable tails of literature behind them. There are no truly “unwritten” destinations. When exotic places are left unvisited, they become intensely fabulized. Even the polar travelers of the 19th century, going toward places then as unknown as the moon, had vivid mythologies to take with them on their long, dark voyages: The Pole was a hidden Paradise, protected by a warm sea; the Pole was an aperture into the center of the earth; the Pole was Nova Zembla, a lost and perhaps once inhabited continent. The bitter and bemused notes that still make reading the literature of polar exploration so bracing derive from the scale of the explorers’ previous expectations. Their reading made them think—in both polar directions, North and South—that it was going to be wonderful, and it was not.

If we want a locus somewhat-less-than-classicus of this kind, a grandfather figure for the self-bemused traveler, we need look no further than the great Romantic poet (and philosopher and scientist) Goethe on his journey to Italy in 1786. He went with a clear set of destinations and a head full of ideas that mixed geology and old buildings and Mediterranean shores; he knew what he wanted, saw most of what he expected to see, and went back to Germany satisfied. And though often delighted, he was never particularly surprised by what he discovered. (“First of all, the Cecilia of Raphael! It was exactly what I had been told of it; even though now I saw it with my own eyes.”)

What he sought and admired would not remotely be like what we seek and admire. He wrote at length about the glories of Guercino, now largely forgotten, and looked right past the greatness of Giotto. He searched in Venice for Palladian churches and ignored the splendors of Venetian gothic. He went away with the same Italy in his mind as the one that he had arrived with. It was, one feels, a journey of confirmation to the nth degree. “How many descriptions, too, of these scenes had I not read before I saw them. Did these, then, afford me an image of them—or at best but a mere vague notion?” he wondered. But recognizing his own plight, he was defiant about it, in words that ring true for those of us who bring our expectations to our experience. “I’ve not gained any new thoughts,” he admitted. “But the older ones have become so defined, so vivid, and so coherent, that they may almost pass for new ones.” There you go, Goethe! We may keep our old pictures in the face of new sights, but the old ones at least are enhanced. They are literally, as the kids say, something to write home about.

There is a different tradition, to be sure, that looks down its happily soiled nose at the rest of us. Lord Byron’s trip to Greece in 1823, intended to inspire the Hellenes in their fight against Ottoman domination, was a trip taken to shed imagery rather than inhabit it. It was not that his head too was not filled with the mythology of classical heroism. But he chose disillusionment in advance. Knowing he would be disappointed by a reality that could not rise to the fantasy in his mind, or that of his supporters, he did it anyway, trying, as his letters reveal, to discipline his dreams with the more modest but essential truth that, whoever the Greeks were now, however far from Homer they might be, they were fighting, like Ukrainians today, for their national freedom from an oppressive imperialism.

But, once in his battlefield, he was very much not on his native ground, and his letters ring querulous and disappointed, and as entertaining as S.J. Perelman outraged by the swindlers in Timbuktu. “I did not come here to join a faction but a nation—and to deal with honest men and not with speculators or peculators (charges bandied about daily by the Greeks of each other),” Byron wrote home. “After all, one should not despair—though all the foreigners that I have hitherto met with from amongst the Greeks are going or gone back disgusted.” Yet the dream discarded was ultimately less appealing than the truth found, which at least had the tang of humanity about it, and he paid for that knowledge with his life, dying of malaria on a foreign field in 1824.

From those two romantic (and Romantic) trips, one might insist, modern travel writing descends—and by extension, the sensibility of the modern self-conscious voyager. On the one hand, existing visions happily inhabited; on the other, stereotypes restlessly dismissed. The traveler goes to accomplish her imagination, or else to mock the world’s clichés. Taj Mahal or biscuit box?

Lesser travelers, lesser measures. Most of us travel as Goethe traveled, albeit without his brains, energy, or Teutonic complacency. The classics of contemporary travel literature (Alexander Frater’s Chasing the Monsoon, Paul Theroux’s railways journeys) are made to the type of the traveler chasing a fantasy, if only of tropical rain on an Indian roof, or the Orient Express as it once must have been.

A few still travel in the Byronic mode, deliberately doubtful, resigned to truth. Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and V.S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival are triumphs of the disillusioned traveler, ready to puncture every glamorous expectation. (But then there is, of course, a form of glamour attached to down-and-outness; it’s no accident that Hunter Thompson borrowed some of the rhythm of Orwell for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.) My friend, the French philosopher and writer Bernard-Henri Lévy, man of courage, wanders the world in self-consciously Byronic fashion in order to bear witness to the struggles and sufferings of others. If there is an element of dandyism in his apparitions (something of which he is well aware), it is exactly in the Byronic pattern. We shall pass this way but once, and the example of witness is what we have to offer—and the more obviously personal our witness, the more potent it may be. He goes to Lesbos to live among the desperate refugees, while others go to Paros to marvel at the blue and white houses. He is who he is, and they are who they are, and what lies between is a kind of pact, negotiated in deference.

And yet, even in the face of our seeming moral failings, there is still something to say in defense of overimaged travelers, those who go out with an idea in their pockets and seek to match it to what they see. First, that this tends, in the lives of those so enslaved, not to be a phenomenon of exotic travel alone; it is a fact of our perception. Send her (or him—okay, me) to the corner store for almond milk, and visions of other stores and other errands will shape her almond milk shopping. And surely it is this ceaseless exchange of images, ideas, and experiences that shapes all our inner lives and ultimately makes civilizations revolve. If romantic-minded travelers are in part retrospective nostalgists, they can also claim to be social scientists, of a kind. We start with a theory of place, and then experience alters the expectation—but it does not make us discard our dreams entirely, merely amend them. Unsatisfying travel writing tends to be pure theory, as in those books about quaint towns in the South of France where the Pagnol clichés crowd in and seem to block all the exits and keep experience out. Truly great travel literature is the anthology of those amendments. It contains expectations disciplined by experience, sharpened by what’s seen. We should not see past Lesbos in visiting Paros—but, visiting Paris, if we insist that the real Paris is that of the banlieues alone, we miss the beautiful continuity of culture that, whatever people may say, is part of what makes our experience of France so rich.

All we need, every day, in every kind of sojourn, is a corrective conscience—and travel often supplies one, in the form of a smarter companion. Romantic travel should not be romantic in the literary sense alone. If there is a secret, a buried code in those long-lost grandfather figures, it is that, beneath the ingenuousness of one and the grumpiness of the other, on their voyages both Goethe and Byron fell in love: Goethe with an Italian girl (still unknown); Byron (surprisingly, given his earlier hetero history) with a beautiful Greek boy. Beneath the complacency of one, the agony of the other, lay the simple fact of unrequited love—the healthiest kind for an artist, since it presses the mind forward, rather than leaving it to lull.

Even Coward’s real subject in that balcony scene was not the trip taken but the companion missed. Elyot had gone to the Taj Mahal with the wrong woman, Sibyl rather than Amanda. Behind the wistful reference to his seeing the world was simply…an invitation, to see it again, with him. The ur-text of every trip is the search for love, for which traveling itself is only an allegory. Quest and question come from the same root, with the difference being that one is active and externalized, and the other passive and internal. A quest is simply a question activated, a trip merely a test that has taken flight. We quest, we question, and, like Amanda and Elyot, we quarrel afterward. To stay within the Coward register, it’s a design for living.

YOUR TRAVEL TYPE REVEALED

Are you a Goethe, going out to search for images already in your head? Or a Byron, pressing forward to new experience? Most of us are one or the other. Take this quiz to find out.

1. IN PARIS, DO YOU:

A. Go to the Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots, in search of traces of Camus and Sartre?

B. Go to the Café Charbon in the 11th and look for a new generation of poets and philosophers?

2. IN LONDON, DO YOU:

A. Take trains to go tramping in rural England to see the houses of the Brontës and the Wordsworths?

B. Remain in London and try to find the next Sex Pistols?

3. IN VENICE, DO YOU:

A. Go in search of the house where the Aspern papers were kept locked up tight by Jeffrey Aspern’s aging lover?

B. Prefer to travel over the water to modern Mestre, insisting that the industrial mainland suburb is where the real Adriatic action resides?

Answers: 1. A. Goethe. B. Byron; 2. A. Goethe. B. Byron—although if you go in search of the St. Martin’s School of Art Common room where they made their debut, you’re still a Goethe; 3. A. Goethe. B. Byron

You Might Also Like