These Two Tech Firms Are Taking AI to the Next Level

Click here to read the full article.

No garment, no matter how durable, how locally sourced, how biodegradable, how many times it can be recycled, can ever be as sustainable as the garment that was never made.

With that eye toward sustainability, as well as cutting waste from the expense line, Rachel Liaw launched Fuse Inventory in 2016, an advanced version of the Excel spreadsheet still being used by many, if not most, companies.

“Everyone wants to be sustainable, but they can’t figure out how to even get to that first step, which is data, making sure you know where the weaknesses are in your supply chain,” Liaw told Sourcing Journal.

Heading into year six, Fuse Inventory counts 40 clients, including DTC shoe-seller Margaux, its beta client dating back to 2016. Margaux attests to a 40 percent improvement on stockouts.

“In many ways, we’ve grown up together,” Margaux co-founder Sarah Pierson told Sourcing Journal. “At Margaux, carrying an extended range of sizes and widths is an essential piece of our mission, and one way in which we deliver exceptional comfort through fit. That said, it adds a layer of complication to what already is a SKU-intensive business. With Fuse’s help, we’re able to monitor inventory levels and spot potential stock-outs before they happen. Between the time saved and revenue reclaimed, the impact has been invaluable.”

Photo Courtesy of Margaux

Using artificial intelligence to form forecasts of how much inventory a business will need of each product to order and where to sell it, Fuse has found its greatest success with CPG (consumer packaged goods) brands, particularly in beauty and cosmetics.

“We’re the only software, really, in the space that has gone from a finished good and breaks it all the way down to all the raw materials, all the way down to ounces on seven decimal points,” Liaw said. “That said, we do work with footwear companies because they have to deal with size assortment. We’re very good at being able to break down your size [needs] historically, by style, which is really hard to do in Excel.”

Liaw said the idea for Fuse came on the way down the ladder of success. She said she had been a lead developer for a foreign language search engine product, but found the tech startup world to be somewhat chauvinistic. So, she decided to get into fashion tech and put herself right on the bottom floor as an intern for the kids’ arts and crafts producer KiwiCo.

“I restarted my career in the warehouse, packing boxes, moving pallets, and just kind of working my way backwards through the supply chain,” Liaw said.

Eventually Liaw started her own company called Parasol Co., a subscription-based site to order diapers and wipes and other baby products.

“I actually built a custom inventory system for that business, because there wasn’t really much out there, as I saw from KiwiCo” she said. “That was kind of the idea behind Fuse—why doesn’t this exist? Why am I building a software that I know everyone else needs?”

Liaw said she saw the true value of inventory software during the pandemic.

“The concept [of building supply chain software] seems very simple—you just forecast your demand and you just buy that, but there’s always disruptions, and I think the pandemic really shone a spotlight on what happens when these disruptions multiply and you can no longer, like, throw people at the problem,” Liaw said.

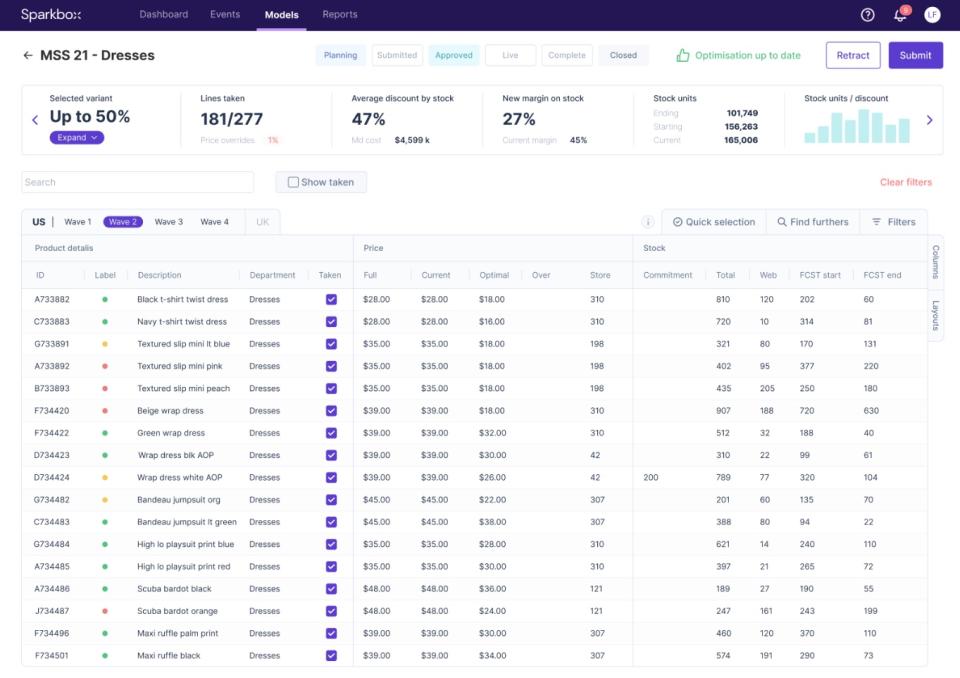

Liaw said she and her co-founder and Stanford classmate Bridget Vuong have seen more than 20 competitors come and go, with more popping up regularly. Among the sooncomers to the space is UK-born Sparkbox.ai, not to be confused with Sparkbox.com, which offers full-service website design. Its co-founder Lindsay Fisher told Sourcing Journal that Sparkbox.ai’s focus is on fashion with British apparel brand River Island and luxury brand MatchesFashion among the vanguard clients.

“We take data from retailers on a daily or weekly basis and we’re using machine learning to essentially understand how each product in each region or zone within their business will continue to perform from a demand perspective,” Fisher said. “We are focused on fashion and seasonal or cyclical categories.”

Fisher said fashion presents a special challenge when it comes to optimizing inventory.

“We build the algorithms to deal with really short lifetime products that are heavily influenced by trend—but it can work for anything,” Fisher said. “We wanted to build fashion first to prove that we could solve the harder forecasting problem first.”

What makes fashion so difficult, is having the right count of sizes and colors and styles making for an almost impossible matrix of factors to get just right.

“You want to be able to react very quickly in order to avoid markdowns and things like that,” Fisher said. “But it’s difficult to look back at something that sold previously and understand what would have sold if you had been in stock in all sizes, and we’ve accommodated for that. We’re able to look at what you would have sold if you had been at 100 percent availability and we use that as a size assumption going forward. It’s just impossible for someone to do that manually, let alone for thousands of products at a time.”

Though not at liberty to name them, Fisher said her company represents fast-fashion brands—the scourge of the sustainability movement, sporting a business model whose only road to redemption might be through tightening waste.

“Our goal is to help those retailers fulfill the demand in the most responsible way,” Fisher said. “If we can help people right-size their buys it means they can buy less and still grow their business.”

Outside the world of AI-infused spreadsheets, there are services that offer GPS-type accounting for the physical items themselves within a brick-and-mortar store.

One such program is RADAR, which announced a partnership last week to install its RFID-driven solution into 500 American Eagle Outfitter locations.

inventory-tracking company’s technology possible. Photo Courtesy of RADAR

“We built a sensor that combines RFID [radio frequency identification] and computer vision and we are able to read and located all RFID-tagged products within a store,” RADAR founder Spencer Hewett explained to Sourcing Journal, adding that pilot efforts with AEO have yielded 99 percent accuracy. “Then we combined the XYZ coordinate data of the RFID tags with the 3D coordinate data of where people are, so basically each sensor has these four cameras on the circumference that extract the 3D pose of people.”

That real-time information translates to an app staff members can use to know exactly what sizes are available on the floor without having to shuffle through and muss up a nicely stacked pile of jeans, and to know what sizes and colors are available in the storeroom without having to leave the interested customer.

“It works best right now in fashion retail just due to the penetration of RFID in that category,” Hewett said. “Apparel and footwear are by far the most RFID enabled.”

Not only can this RFID-enabled technology improve a customer’s experience in finding what they want, it can speed up the payment process, too. In fact, it was standing in a long line with a friend during a semi-annual sale at Victoria’s Secret that the idea sprung on Hewett.

“I ended up betting her that I could figure out a way to eliminate lines and then just kind of spent that time thinking about how you could attribute products to people, then when they left the store automatically they wouldn’t have to wait in line,” Hewett said. “If you can locate every item and every person, and those people had their payment information saved on the app on their phone, and between these three signals we could charge them for what they left with.”

RADAR does not yet have that technology as part of its package, but it could be a fruit of the company’s latest funding round that takes it over $50 million raised to date.

“The goal of the company was to index every object in the world, so the best way to start is with retail but over time it can be extended into other use cases potentially outside of retail,” Hewett said. “I see a lot of use cases and a lot of potential value and fulfillment centers in hospitals, manufacturing, refactoring, and then, eventually I think, people’s homes… But that’s going to take some time to get there.”