How Do You Turn Outdoors Gear Into True Fashion?

Gorpcore—utilitarian clothing by the likes of Patagonia, The North Face, Salomon, and a slate of cult brands based abroad—has become one of menswear’s central driving trends over the past five years. The phenomenon has not escaped the attention of Kiko Kostadinov, the 32-year-old Bulgarian-British designer who is one of the industry’s freakiest and most thoughtful young talents. “I think everyone wants to be Patagonia or Arc’Teryx,” he said, in a Zoom conversation last week. The appeal of being not a fashion brand, but a technically-minded, vaguely ethical corporation, seems obvious.

But Kostadinov scrutinizes everything, especially the obvious. He has developed a cult following among fashion fanatics, especially students, for creating titillating, almost Dadaist clothes that stretch the utilitarian into the decorative and vice-versa—jockey helmets, racing stripes, shell jackets, and Renaissance capes have all been hero pieces in Kostadinov’s output. And, like most millennials, he’s hyper-tuned into industry trends and realities, equal parts artist and industry critic. (Jonathan Anderson, though more established, thinks the same way.)

“There was a lot of thinking of how to escape,” Kostadinov said of the clothes he debuted last Friday, his Fall 2021 offering. He was speaking about how the psychological impact of the past year shaped this collection, but also about the design confines of the performance wear—gorpcore—that is increasingly dominating high-fashion menswear. He mused on the limiting assumptions behind those clothes: “Things looking too outdoor, or too Sci-fi, or futuristic or technical.” (It made me think: there is indeed something lurking beneath the placid pragmatic surface of gorpcore. What’s with the survivalist paranoia? Why is there a sense of embarrassment around design that isn’t purely functional? Why are men so eager to get to the future?)

“So it was like, how do you challenge this?” Kostadinov said. “How do we break some of those things?”

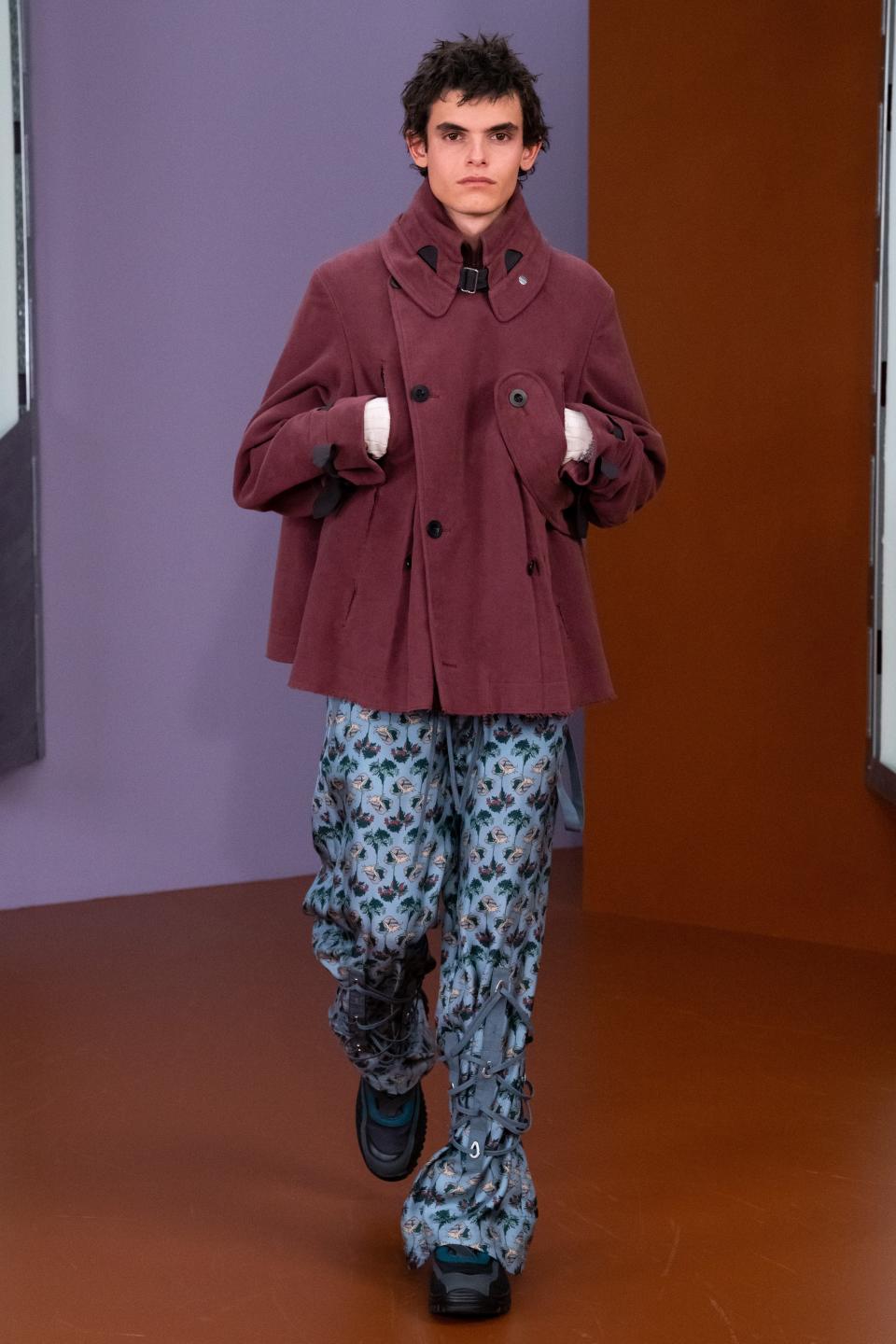

In response, Kostadinov’s clothes get at a much more ambitious idea of escape. The collection contains three sections describing his moods (our moods, really) over the past several months: one week, he wants to live in a cottage in Alaska or Dorset or back in Bulgaria; the next week he wants to “travel the world and buy clothes and spend money and see exhibitions and go to parties”; and then he feels like he’s on a rollercoaster of in-between. This third section is perhaps the most familiar to us all. It’s like “a glitch,” he said, between the first two moods.

To present the collection, Kostadinov came up with a rather insane concept: while he shared a concise 30 looks with the press, he also had his models try on every look in a bunch of different ways. So if you go on his site and select “Silhouette,” you’ll see some 90 looks. It begs the question: Why? “It was very hard to decide which one was first, middle, or last—what’s past, present, future, whatever.” He went on, “You don’t really know if necessarily [one look] should be the futuristic part. Why could it not be the past?” It seems kind of crazy—and indeed, he said the collection was kind of a nightmare to put together—but it was one of the most effective summations of the past year. Many of us are careening violently between an urge to be in a distant future, and a wistful longing to retreat into a past, often one we never knew. (Who knew all our friends had these country houses just waiting outside of the city? Who knew so many of them knew how to chop wood? Who knew those prairie dresses and Gore-Tex jackets would suddenly become so un-ironic?!)

He wanted the clothes, especially in the third section, “to feel worn or maybe found—like they’ve been through something,” but he didn’t want to do something as simple as fading them. He sliced holes in the knees of his trousers, and gave many of his jackets raw hems. That was one way he screwed with the gorpcore; the other was to mishmash styles and references, putting panels of Chanel-y boucle across windbreaker jackets and coats. (Grail alert!) He also created a weird, oversize sort of pocket that can slip over anything from a pant leg to the wearer’s neck, making a skirt or an apron top or an otherworldly layer. It reminded me of the kind of funny little bags someone might find in the back of REI and suddenly turn into a cult internet objet whose purpose becomes moot through the process of fetishization. Fashion at work!

Many find Kostadinov’s clothes somewhat impenetrable—the depth of his ideas, and the references, which can seem obscure for the fashion world, are almost too good for our atmosphere of dumdum communication. All this means, of course, is that everyone should be paying much closer attention.

Originally Appeared on GQ