How Tulsa's Greenwood Became a Thriving "Black Wall Street"—and What Its Deadly Destruction Means Today

How does a city atone for killing as many as 300 of its Black citizens? How do you pay restitution for destroying homes and businesses worth more than $500 million today, and robbing future generations of family wealth? That’s what Tulsa, Oklahoma’s city leaders and citizens have been grappling with for just about 100 years, since riots led by a white mob killed hundreds, displaced thousands, and destroyed what as once a thriving center of Black business.

In the years after emancipation, Oklahoma emerged as a state where Black people could prosper. “At one time, Black people in Oklahoma owned 3 million acres of land,” says James Goodwin, publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle, a Black newspaper that’s marking its own centennial this year. People who were once enslaved received land grants in the 1890s. Marketers at railroad stations recruited freedmen to come to help settle Oklahoma territory. Soon, there were more than 50 thriving black towns in Oklahoma, including Boley and Langston.

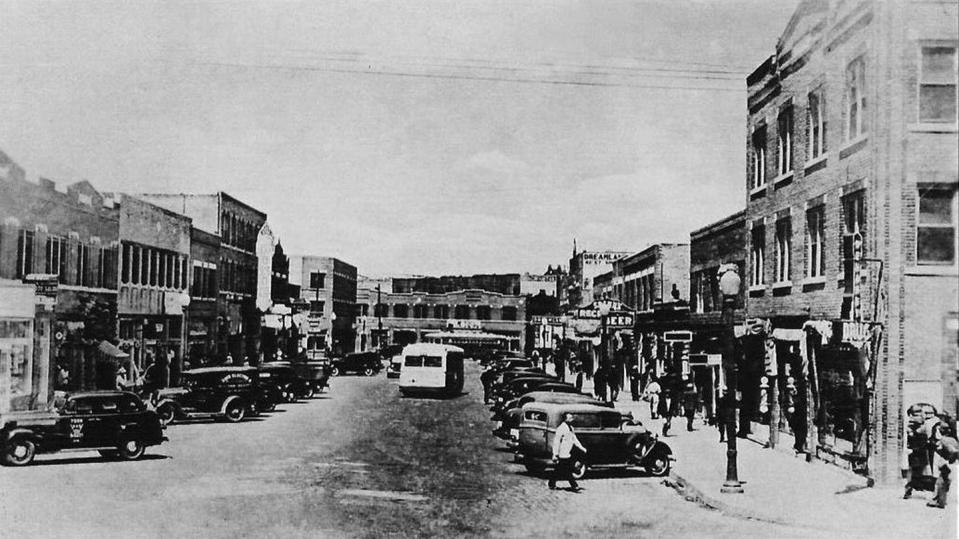

The most impressive, though, was Tulsa’s Greenwood District, a 40-block community bordered by Archer to the south and Pine to the north. Due to segregation, Black people could only do business with each other. The district boomed with Black-owned hotels and hospitals, banks, dry cleaners, restaurants, and the grand Dreamland Theater. It was the pride of Black people across the U.S., who called it the Negro Wall Street, a testament to Black entrepreneurship, hard work and success.

“Jim Crow was designed to subjugate us, but [Greenwood] proved that white supremacy was a big white lie,” Goodwin says. “Here you have children of slaves prospering in an environment they were never intended to be prospering. They proved that with assets, one could develop a community like any other community. Color was not the factor in determining one’s wealth or poverty.”

Greenwood’s prosperity inspired jealousy, says Goodwin. Hannibal Johnson, author of several books on Tulsa including Black Wall Street 100: An American City Grapples With Its Historical Racial Trauma, says white people couldn’t handle seeing Black people who were more well off. “Land lust is a factor,” Johnson says. “We know the land was coveted by other people.”

Whites attacked Black communities across the US in what was called the Red Summer of 1919. Tulsa’s particular massacre started after a young Black man named Dick Bradford was thrown in jail for “assaulting” a white young woman operating an elevator. His "crime" remains dubious: Newspapers say he either tripped and grabbed her arm or stepped on her foot, according to a report by Maurice Willows, director of Red Cross disaster relief. Local media ginned up the community, and a large white mob went to the jail to lynch him. Black men showed up to protect him and they were quickly overpowered. Whites plundered and attacked Greenwood with machine guns and turpentine Molotov cocktails dropped from airplanes.

By the afternoon of June 1, only a few buildings in Greenwood were still standing. As many as 300 were murdered, and eight pregnant women miscarried. Some wounded fled to Kansas City, more than 250 miles away. More than 6,000 Black survivors who stayed in Tulsa were rounded up, put in internment camps, and issued dog tag IDs, according to Red Cross archives. They could only leave if white employers came and vouched for them. In 48 hours, Tulsa’s self-sufficient Black community was returned to living conditions that resembled slavery. Months later, hundreds still in the Red Cross camp were conscripted to build latrines and do other work.

The Greenwood District was rebuilt, mostly with the same elbow grease and grit that built it the first time. Insurance claims for damages were denied, because the event was deemed a riot.

The community, and the prime real estate it occupied, remained under assault even after the shooting ended. City officials foiled Red Cross plans to help residents rebuild by changing the building code to forbid wood-frame homes. A planned train depot was moved to the Greenwood District, and expanded.

Tulsa was one of the first cities in the US to embark on urban renewal in the 1960s. Many call it "urban removal" because of the way it moved more Black residents out, and then pierced the heart of the once-thriving community with Interstate 244.

In the lead up to the centennial of the massacre that started on May 31,1921s, Tulsa has been humming with commemorative events: Greenwood Rising, a modern history center and museum, is hosting a prayer vigil and televised event. There’s an Ironman race , film festival, and a golf tournament. Actor Hill Harper, an Iowa native, is hosting a wealth-building and investment conference with speakers including John W. Rogers of Ariel Investments, a Tulsa native whose family lost a fortune in the massacre.

Today, President Joe Biden will visit the city to commemorate the centennial, following his proclamation yesterday "to commemorate the tremendous loss of life and security that occurred over those 2 days in 1921, to celebrate the bravery and resilience of those who survived and sought to rebuild their lives again, and commit together to eradicate systemic racism and help to rebuild communities and lives that have been destroyed by it."

There’s a Legacy music festival and a star-studded Greenwood Cultural Center Sunday brunch with Oklahomans Alfre Woodard and Garth Brooks. It’s hard to keep up. And that’s not counting all the upcoming books, plays, television shows and documentaries about Greenwood District. But, many residents say, something is missing.

“We’ve got so many people capitalizing on our stories...and none of that is benefiting the Tulsa African-American community,” says Sherry Gamble Smith, co-founder of the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce. “There’s a lotta fluff going on but behind the scenes, nothing truly has been done. I’m fearful of what’s going to happen after this year. We’re hopeful, but we don’t trust that the community that lost the most is ever going to get to the place where they’re successful here in Tulsa.“

In 2001, the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 made five recommendations, including scholarships for Black descendants of massacre victims and direct restitution payments to descendants. State and city officials haven’t done any of those things. But they have dedicated a memorial park: the John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park.

“I’m sick of dedicating trees and benches,” says Vanessa Hall-Harper, the councilor for District 1 in North Tulsa. “Until we get to the point where we can talk about tangible, real repayment in the form of land and money–greenbacks–then we have not touched upon reparations. That to me is more symbolism, more of the same empty gestures.”

Indeed, a century after an event that is still scrubbed from the history textbooks in most classrooms, many Black residents feel they’re still getting grand gestures and words instead of restitution or concrete financial programs to help Black Tulsans regain the economic autonomy and land ownership they lost.

Hall-Harper says that’s by design. “Money is power, resources are power and land is power,” says Hall-Harper, co-founder of the Black Wall Street chamber of Commerce. “It’s racism. And we are not going to do anything that’s going to repair and certainly we’re not going to do anything to change our power structure. That’s why they’re so adamant against any form of reparations as far as payments are concerned.”

Today, Smith says Black people own just two buildings in the former Greenwood district. Black home ownership lags behind that of Whites, 58.2% to 34.8 according to the 2019 Tulsa Equality Indicators Report.

The city is working on long-range initiatives, including the Peoria Mohawk Business Park to bring higher wage industrial jobs, the Evans Fintube project to turn an old ironworks near Greenwood into a mixed retail, entertainment and housing development, and a tax-increment financing district to increase transit between Greenwood and other parts of the city, according to Kian Kamas, Tulsa’s chief of economic development.

One bright spot has been Oasis Market, a full-service grocery store that opened in May. For the past 14 years, North Tulsa has been a food desert, without a grocery selling fresh fruit, vegetables and meat.“That’s part of the reason why the life expectancy rate in this community is 11 years shorter than in any other community in Tulsa,” says Aaron AJ Johnson, the store’s owner-operator. “That’s an inequity Oasis will change.”

Tomi Keys, who lives nearby, stopped in on a Thursday for some fresh collard greens and smoked turkey necks. She used to struggle to make the 10-mile journey to the closest market. “Imagine me on the bus in a wheelchair trying to get some fresh greens,” says Keys, 57. “I am no longer in the desert.” A public-private partnership helped fund the market: The George Kaiser Family Foundation, Zarrow Family Foundations, and the TEDC Creative Capital, led by Rose Washington, each contributed $333,000. Besides offering fresh food, Johnson says Oasis pays higher than average wages, helps employees learn about entrepreneurship, and has a cafe that will host education on wellness.

Smith credits Mayor G.T. Bynum with being the first mayor to initiate a search for mass graves from the massacre, which he calls a “murder investigation.” (It will begin today). But she was stunned to learn that Bynum told a May Republican Women’s Club luncheon that he opposes monetary compensation for survivors or descendants of Tulsa’s massacre, despite evidence that city officials armed the white mobs, and covered up the massacre for decades. “That’s showing us you don't care about your city, your people of color, the Black people in your city,” Smith says. “It’s definitely adding insult to injury. There is no healing that is going on in 100 years. Our hearts are still bleeding.” She noted that Evanston, Illinois, and Asheville, North Carolina, have paid reparations for slavery and past discrimination.

Hall-Harper says she’s focusing on finding ways to support Black entrepreneurs, and keep the spirit of the 1921 Black Wall Street alive. “My hope is not necessarily in the system,” Hall-Harper says. “My hope is in the people.”

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

Maria C. Hunt is a journalist based in Oakland, where she writes about design, food, wine, and wellness. Follow her on instagram @thebubblygirl.

You Might Also Like