Truman Capote as Pygmalion: how the 'tiny terror' threw his adopted daughter into high society

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

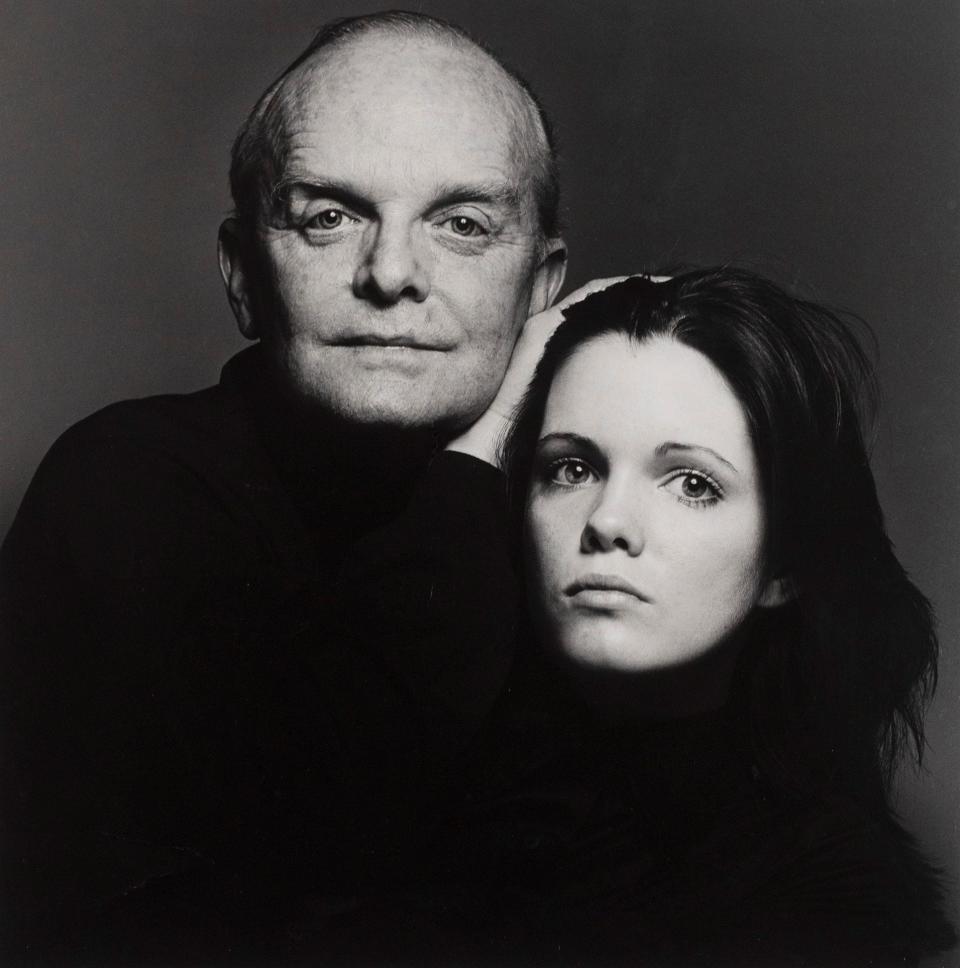

In the mid-1970s, in a real-life version of Pygmalion, the American writer Truman Capote unofficially adopted Kerry O’Shea, a teenage schoolgirl from suburban Wantagh, Long Island. He was a welcome substitute for Kerry’s absent father – even though Capote was the lover for whom that father had left his wife and children. Capote took Kerry under his wing, changing her name to Kate Harrington and introducing her to everyone from Andy Warhol to Richard Avedon.

At the time, Capote was as much a professional celebrity as a writer, with an acidulous wit that made him the darling of New York society and the talk show circuit. His diminutive figure, flamboyant dress sense and nasal southern drawl – like the cartoon dog Droopy on helium – were familiar to people who’d never read a word of Breakfast at Tiffany’s or In Cold Blood.

In Ebs Burnough’s spellbinding new documentary film, The Capote Tapes – a collage of reminiscences from friends (and enemies) living and dead – the most intimate insights come from Harrington, speaking about Capote on camera for the first time. Talking to me from her home in Wyoming, she recalls the explosion of the exotic Capote into the lives of her “ordinary Irish Catholic family”.

When she was 11, her father, John O’Shea, announced that he was leaving his job as a bank manager to become Capote’s business manager. “He told us they met at the bank because Truman was buying real estate, but my dad’s bank was nowhere near where Truman lived. Gerald Clarke [Capote’s biographer] told us that they actually met at some gay bar in New York.”

Capote became a regular presence in the family home. Harrington remembers his first visit: “He came in this limousine and all the kids in the neighbourhood ran over to look. I had to run into the kitchen and put a tea towel over my face because I was laughing at the sound of his voice.”

When O’Shea left to be with Capote, the young Kerry and her family were overjoyed. “My dad was a violent alcoholic and we were terrified of him, so we felt incredibly grateful to Truman for taking him away,” says Harrington. “He was like our answered prayer.”

The relationship between Capote and O’Shea unfolded as an endless sequence of fallings-out and makings-up; at one point it deteriorated so much that Capote hired some hoodlums to rough up O’Shea, and they set fire to his car.

Harrington never saw her father again after he left, apart from a glimpse across the room at the memorial service after Capote’s death. He refused to support his family, and her “dear, sweet” mother, Peggy, was also driven to alcoholism because of their dire finances.

Desperate to help with money, in 1976, Kerry, aged 14, decided to telephone Capote out of the blue: “He knew a lot of important people, I wondered if any of them needed a helper.” Capote invited her to lunch in Manhattan and suggested she leave school and find a job: “He said, ‘Smart people don’t need to go to school, and you’re smart.’ I said ‘No way.’ So he said, ‘Well, OK, the only thing you can do if you’re still going to school is be a model.’ And that was shocking, I never saw myself that way at all.”

She signed up with Wilhelmina Cooper’s model agency; her name was similar to that of another girl on the books, so Capote rechristened her Kate after one of her grandmothers, while Harrington was her mother’s maiden name. “I thought it was just a game. I didn’t think it was real or that this name would last for so long.”

Harrington would stay at Capote’s 22nd-floor apartment on the UN Plaza when she was in New York City for modelling jobs, and then began to spend more time there as life with her mother in Long Island grew more difficult. The apartment boasted “incredible views, beautiful paintings and Japanese furniture, but also things like a big plastic duck that was a night light, and he collected stuffed snakes, and ceramic frogs”.

Capote, she says, “was lovely to live with, just gentle, kind, funny, very nurturing. I had my little room” – with “H Golightly” on the door in honour of the heroine of Breakfast at Tiffany’s – “and he had his room where he would write often, sometimes in his bed.” He had some odd habits: “he put his mail straight in the incinerator. There’d be a lot of books in there that people would want quotes from him for, but he would just dump it in and laugh his head off.”

The first time she came to stay with him, she recalls, he opened the door and gave her a notebook. “He said, ‘You can stay, as long as you keep a journal.’ I asked him why. He said, ‘Because your life’s about to change and this will help you to hold on to your true self.’” Was she never overwhelmed by this new celebrity-filled life? “No. My mother brought me up to believe nobody is better or worse than me. Besides, Truman was never impressed by anyone else, so I just copied his attitude.”

Capote’s benevolence to her seems at odds with his reputation as the bitching, back-stabbing “tiny terror”. Perhaps, as Gerald Clarke sourly suggests in his biography, the novelist only “took John’s place as head of the O’Shea family” and “erased John’s name from his favourite child” in order to torment his on/off lover.

What does Harrington think was his motivation? “He seemed to like the idea of revealing the world to me. He introduced me to literature, we would go to the ballet and see Mikhail Baryshnikov, we would go to art openings. It was like blinders coming off.” He could be overzealous in the Henry Higgins role, however, especially in forbidding her from telling anyone she was from unglamorous Wantagh: “It took me years to shake off feeling ashamed of where I’m from.”

Capote even took her to Los Angeles in the unrealised hope of launching her on an acting career. She had a memorable encounter with Ryan O’Neal, who offered to take her home after a party to get some tips from his Oscar-winning teenage daughter, Tatum. “[Truman] was miming ‘no, no, no’, but I was 17 and I thought, I’ve never defied Truman before, I’m gonna have a bit of fun. So he said” – she imitates the Capote gurgle – “‘all right, but I’ll be waiting up and we’ll be talking, miss.’”

Tatum O’Neal did not oblige – “she was incredibly mean to me” – and as for Ryan, “he sort of seduced me and I ended up spending the night… The next afternoon at the hotel, he sent me a bunch of pink roses, with a message: ‘A perfect evening, love Ryan.’ Truman said I could never see him again, that was that.”

In his final years Capote was at work on Answered Prayers, a Proustian epic about the New York beau monde, which seems to have disappeared – some commentators think it largely never existed, but Harrington insists that the pile of yellow pads comprising the manuscript “were all filled, all the way to the top”.

Disastrously, he published snippets of it in magazines, spilling the secrets of his “swans”, as he called his circle of chic women friends at the centre of Manhattan society. They turned against him – “I remember him saying once, ‘What did they think they had around them, a court jester? I’m a writer’” – precipitating a “downward spiral” into alcohol and drug abuse.

Harrington repaid his kindness with devoted companionship in his wretched final years. “One time, he started drinking after coming home from rehab, and I was so upset I said, ‘why do you have to drink? Isn’t it enough that I love you?’ And he said, ‘Oh darling if only it was.’ And he said, ‘the one big reason, after all the psychotherapy I’ve been through, it’s because my mother killed herself, I can’t get past it.’” Nina Capote, who had never accepted her son’s homosexuality, committed suicide in 1954.

Capote died in 1984 from liver disease, aged 59. Harrington is delighted that Burnough’s documentary takes the trouble to show his softer side, and that the screening at the Toronto Film Festival “was filled to the rafters”. “People still care about him,” she says. Harrington has heard that Hollywood producers are interested in her story but, worried “they’re going to do an Auntie Mame-type movie”, she’s busy writing her own account.

Does she admire any of the film portrayals of her adoptive father? “The only one I ever liked was Capote with Philip Seymour Hoffman, although I didn’t understand why [Hoffman] did not think humour played a part in that role. But it was accurate in terms of the diligence and the emotion behind his work.”

Since Capote’s death Harrington’s career has included spells as style director at Vanity Fair and as a film costume designer; after working on a number of movies with the director John McTiernan of Die Hard fame, she went on to marry him in 2003; they are now divorced.

The fact that Harrington has a daughter called Truman attests to the importance of Capote in her life. “I became an artist in my own right because of him,” she says. “He gave me the gift of culture and planted the seeds in me of my own creativity. He changed me.”

The Capote Tapes will be available at altitude.film and digital platforms across the UK from Friday January 29