The True Story of Jean Tatlock in Oppenheimer

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In Christopher Nolan's new epic Oppenheimer, Florence Pugh portrays Jean Tatlock, J. Robert Oppenheimer's lover who meets a tragic end when she dies by suicide. Though Pugh is barely in the three hour plus film, her performance is impactful, and leaves the viewer wanting more.

If you got out of the movie theaters and immediately thought to Google Jean Tatlock, you're in the right place. Here's the true story of the woman depicted on screen:

She was a psychiatrist.

Jean Frances Tatlock was the daughter of John Strong Perry Tatlock, a professor of English, and Marjorie Tatlock (née Fenton). Born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Tatlock went to Cambridge Rindge and Latin School in Cambridge, Massachusetts before enrolling in Vassar. She graduated in 1935 and then went to Berkeley to complete prerequisites for medical school. Later, she attended Stanford Medical School, where she graduated in 1941 as a psychiatrist.

She was a member of the Communist Party.

While at Stanford, Tatlock wrote for the Western Worker, the Communist Party's west coast periodical.

Tatlock met J. Robert Oppenheimer in Berkley in 1936.

At the time, she was a graduate student and Oppenheimer was a physics professor. Oppenheimer described their relationship during his 1954 security hearing as follows:

In the spring of 1936, I had been introduced by friends to Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a noted professor of English at the university; and in the autumn, I began to court her, and we grew close to each other. We were at least twice close enough to marriage to think of ourselves as engaged. Between 1939 and her death in 1944 I saw her very rarely. She told me about her Communist Party memberships; they were on again, off again affairs, and never seemed to provide for her what she was seeking. I do not believe that her interests were really political. She loved this country and its people and its life. She was, as it turned out, a friend of many fellow travelers and Communists, with a number of whom I was later to become acquainted.

Oppenheimer reportedly proposed to Tatlock twice. After he wed Kitty Harrison, the scientist still saw Tatlock a few times, and some historians believe he had an affair with Tatlock while working on the Manhattan Project.

Furthermore, Tatlock introduced Oppenheimer to John Donne's poetry. It's possible that Oppenheimer named the "Trinity" test as a tribute to her and the verse.

She questioned her sexuality.

Tatlock reportedly wondered whether or not she was gay. According to An Atomic Love Story by Shirley Streshinsky and Patricia Klaus, she wrote to a friend, "there was a period when I thought I was homosexual. I still am, in a way, forced to believe it, but really, logically, I am sure that I can't be because of my un-masculinity."

There's some mystery around her 1944 death.

While Jean was being treated at Mount Zion hospital in San Francisco for depression, her father found her dead in her apartment. There was an unsigned suicide note, which read, "I am disgusted with everything... To those who loved me and helped me, all love and courage. I wanted to live and to give and I got paralyzed somehow. I tried like hell to understand and couldn't... I think I would have been a liability all my life—at least I could take away the burden of a paralyzed soul from a fighting world." Most agree Tatlock died by suicide.

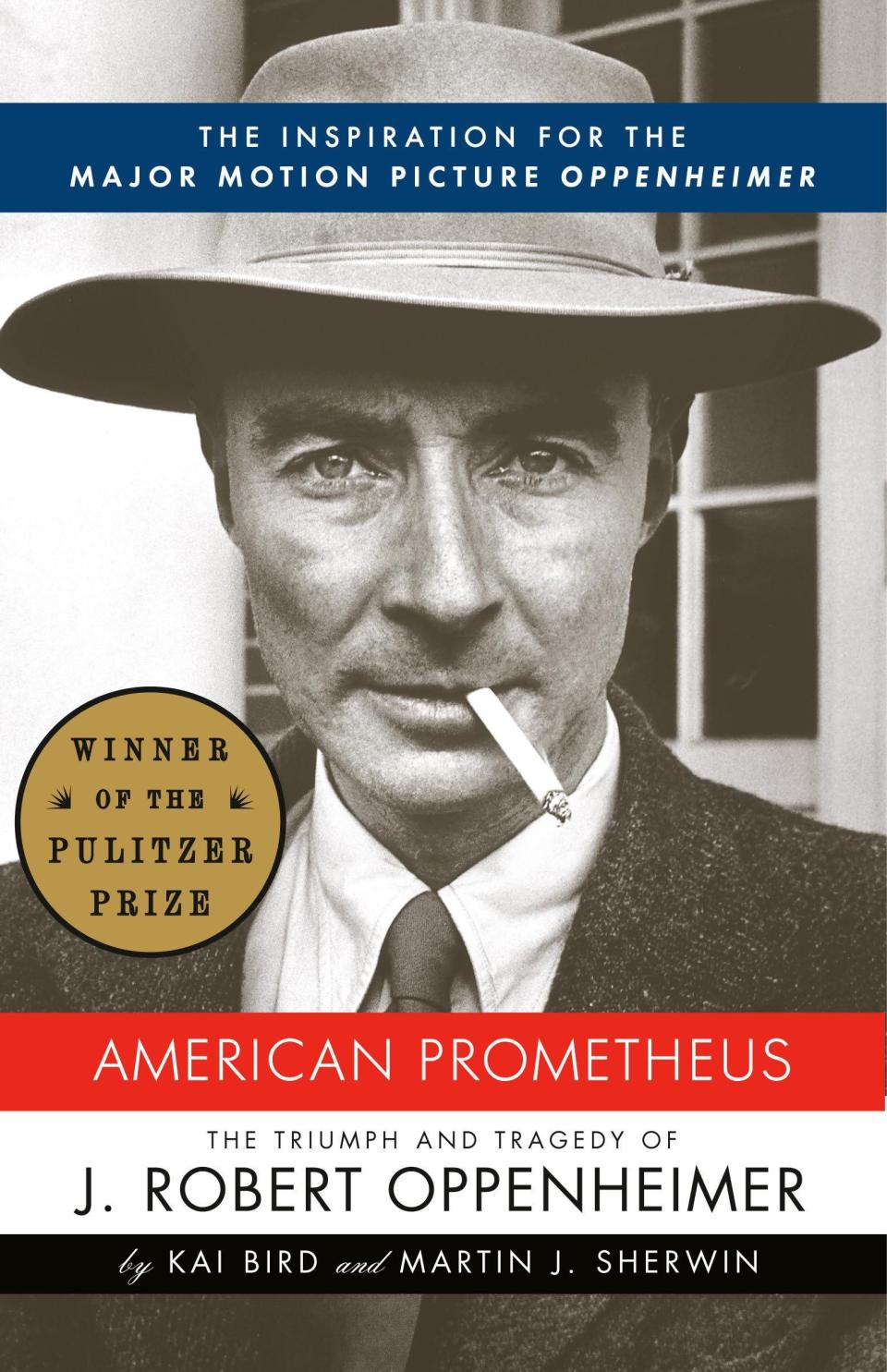

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer

$15.99

amazon.com

But some historians—including Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, authors of American Prometheus, which forms the basis for Nolan's Oppenheimer—question her death.

"According to the coroner, Tatlock had eaten a full meal shortly before her death," Bird and Sherwin write. "If it was her intention to drug and then drown herself, as a doctor she had to have known that undigested food slows the metabolizing of drugs into the system. The autopsy report contains no evidence that the barbiturates had reached her liver or other vital organs. Neither does the report indicate whether she had taken a sufficiently large dose of barbiturates to cause death. To the contrary, as previously noted, the autopsy determined that the cause of death was asphyxiation by drowning."

The authors continue, "These curious circumstances are suspicious enough—but the disturbing information contained in the autopsy report is the assertion that the coroner found 'a faint trace of chloral hydrate' in her system. If administered with alcohol, chloral hydrate is the active ingredient of what was then commonly called a 'Mickey Finn'—knockout drops. In short, several investigators have speculated, Jean may have been 'slipped a Mickey,' and then forcibly drowned in her bathtub."

Of course, this is all speculation; Bird and Sherwin agree there's not enough evidence to definitively say one way or another.

You Might Also Like