“I Tried to Do More With Less”: A Chat With Famed Free Soloist Henry Barber

This article originally appeared on Climbing

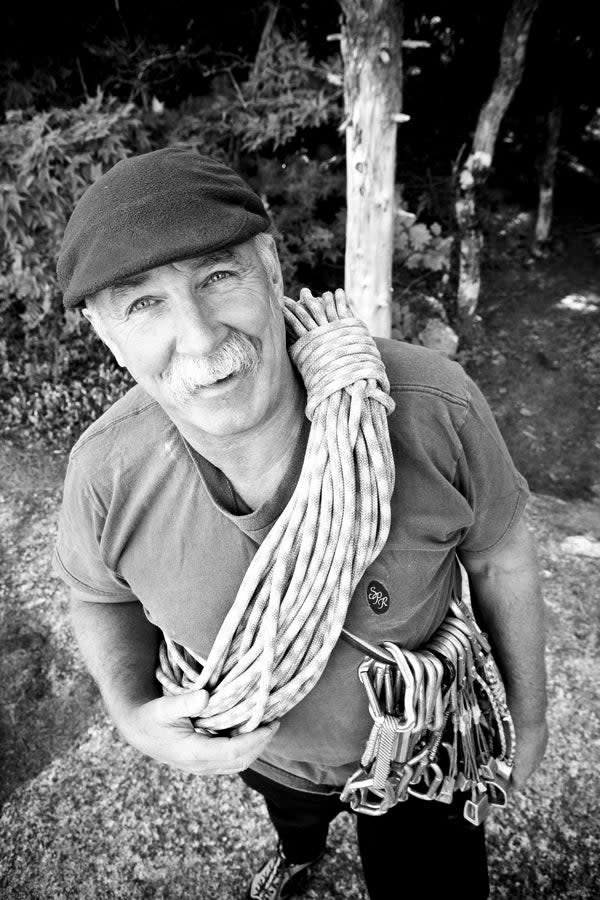

Born in Boston in 1953, Henry Barber is a prolific first ascentionist, pioneer of clean climbing, and free soloist; in the 1970s, he was perhaps the world's best free climber, period. In 1973, "Hot Henry" blew away the Yosemite establishment with a supernatural onsight FA of the much attempted Butterballs, a 5.11c tips crack, followed shortly thereafter by a 2.5-hour free solo of the Steck-Salathe (V 5.9), on Sentinel Rock. That same year he documented 325 days of climbing. Barber was also one of the first American climbers to travel widely, pushing standards everywhere he went. In Dresden, Germany, he climbed in the local style, chalkless, barefoot, and with jammed knots for protection. In Australia, they still talk about his visit in 1975, when in a matter of days, he pushed free-climbing standards two full number grades. As a free soloist, he was without peer, routinely onsighting 5.10 and putting up 5.10 solo first ascents. In 2008, when this interview took place, Barber worked as a motivational speaker and still climbed with his trademark swami belt and rack of nuts and hexes (no cams).

THE INTERVIEW

Synnott: How did you first get into free soloing?

Barber: I got into free soloing because I didn't really have anyone to go climbing with. When I really started to climb solo was in the rain. In the Shawangunks soloing in the rain was great because the wasps aren't out. It's better in the rain when your feet are wet and your hands are wet and there's no chalk. But if your feet are wet and the rock's dry, or the rock is wet and your feet are dry, it's really slick.

Synnott: Did you do anything special to prepare for your solos?

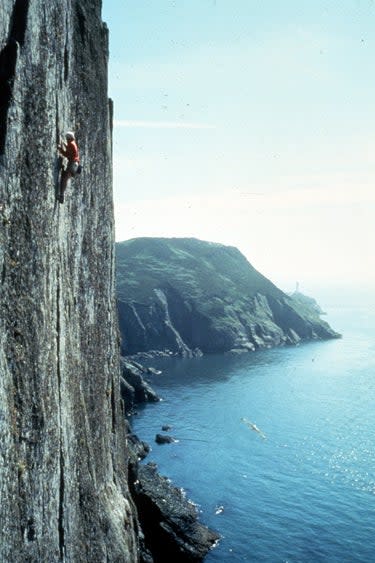

Barber: In order for me to solo I have to climb 250 to 300 days a year. To me it's all instinct. It's that awareness that's important when a hold snaps or a bird flies out of a crack. I've had my hat knocked off by a seagull, and my leg knocked off the wall by a cormorant while soloing in the United Kingdom. Anything that was steep and overhanging with a crack was fine for me, but anything that had a slab in it scared the hell out of me. Because it was insecure.

Synnott: Any sketchy moments you'd like to share?

Barber: I got into big huge battles in my head a lot, like on Gorilla's Delight, in Boulder Canyon. I completely sandbagged myself. I was going up this nice finger and hand crack, and then you have to pull up on this slab and all of a sudden you have to completely switch your rhythm, and your style. The slab is the second crux, maybe 5.9+, and it was underrated. I went on it thinking this is going to be OK, but since I don't do the climbs beforehand, I kind of set myself up. I had said to myself, well I can do this because it's 5.9, and that's a bad mentality to get yourself into.

The thing that I like about soloing the longer routes is that you don't know what's going to happen until you get to a point. It's really great to be on a big wall like the Steck-Salathe, where you're climbing the weakest line on the face--there's nowhere you might be able to traverse off. Once you've done the first five or six pitches and you've done that face move, you're trapped between two things, and I like how black and white that is. I don't think about that before I go, but then as soon as I pass that point my mind is in a whole different place--you're living in another world. I did 80 percent of solos onsight because I never wanted to have a preconceived idea of what it was going to be like. If I'm going to do something that I've done before, the question is why, and the answer is, because I thought it was easy. But if it ends up being wet, or a hold breaks, and it ends up being harder than you thought, then you start getting second thoughts, you get into the negativism. I much preferred to go into them totally fresh.

Another reason I loved soloing was for the euphoric feeling afterwards. I remember soloing the North Face of Capitol Peak [5.9] and coming down and making love to my girlfriend. Unless I was Carlos Castaneda, I couldn't describe what that's like, but that's what really almost addicted me to it; not the struggle and focus during the climbing, but the release afterwards. I've never done drugs, but it's got to be like that, because it's intense.

The accomplishment in the end is providing safety for yourself. On an X route, I'm not trying to make an X route. I'm just trying to work with the rock. If it gives me cracks, I put gear in; if it doesn't, I just wasn't a bolt guy.

Synnott: Where did you grow up?

Barber: I grew up around Wellesley and Sherborn, outside Boston. I went to public school. I was a complete dork, probably still am, I'm not sure. I couldn't do a pull-up, couldn't do a push-up. I played baseball as a kid 24-7, but I had no talent. I was terrible. I was an anemic hitter and I couldn't throw. But I loved it. I played on the Sherborn junior-high team and little league in Wellesley. I used to practice in Sherborn and ride my bike 10 miles to play in Wellesley. I had a single speed and I did it three times a week. I loved the independence. Finally, I got bullied and I had bad coaches and I was, like, screw it, I'm going to be a rock climber. I went to a summer camp and spent an entire summer hiking around the White Mountains. I'd see the people coming down off Cannon Cliff with ropes and I said, “I have to do that.” My parents sent me to Ashcrofters, in Aspen, Colorado, where Lou Dawson, Neil Beidelman, Don Peterson, and John Middendorf all learned to climb. I came back and I started climbing every day. Pretty soon I started scheming to get out to Boulder or Yosemite.

Synnott: When did you first realize that you actually had some talent?

Barber: It took me five years solid to get decent. My first 5.10 was Final Exam, on Castle Rock in Boulder Canyon [since upgraded to 5.11]. Jamie Logan, who did the first ascent of the Emperor Face, and some others were working it and couldn't do it. I walked up and I did it. And I'll never forget it, because the way those guys treated me was really exceptional. They were just very sincere and they made me feel really killer good. Because of my baseball, I kind of looked at everything like a fluke, a mistake. That's why later we all rated these Cathedral Ledge routes 5.8 and 5.9--we just figured we couldn't possibly be climbing the hardest routes in the world.

Synnott: When was your first season in the Valley?

Barber: I went to Yosemite in 1972 and I did the first continuous ascent of New Dimensions. But the Yosemite lads didn't really like me. I don't really know why. In my particular case, I was 19 and I wasn't very mature. I could be brash and offensive one moment, and then humble and quiet the next. They didn't like that dichotomy between brazen and the quiet, wallflower type. Bridwell and Mark Clemens were really, really good to me initially. They were really supportive. I had locking carabiner on my swami belt, and they were like, "Dude, you don't want to be doing that. You want to be tying in." I didn't really get the cold shoulder until the following year, when I did the Steck-Salathe, Butterballs, and some other stuff. After that they would give me the stinkeye. It could have been a jealousy thing, or I could have been an asshole, I don't know. It just got worse over the years.

Synnott: Why is it that you don't use camming devices?

Barber: I love the freedom I get from the small amount of gear I use. I carry 24 to 25 nuts, including hexes. I have cams, I've just never used them. They're still in the box with the hangtags. Someone gave them to me back in the 1980s. They're awesome, brilliant devices, fantastic technology. I've got nothing against them--I just never needed them. That's what I want people to take away from my climbing--that I tried to do more with less, all the time.

Synnott: Does being the best come with any special responsibilities?

Barber: I think you have to have a certain kind of personality to be at the cutting edge, when you're a step beyond everybody else. If you're ahead of your time, it's inevitable that people are going to cut you down to size. You have to be humble and apathetic. It helps if you can be genuinely interested in other people and what they're doing.

Synnott: What do you think of the local climbing scene in North Conway?

Barber: Back in the 1970s and early '80s, I was really lamenting being in the Northeast, because I was envious of the high-altitude climbers in the Seattle area, guys like Roskelley who were going to the Himalaya. I remember wishing that there was more of that scene in the White Mountains. But it's slowly developed, and I now think the scene in the North Conway area is probably the coolest climbing scene in the country. I think this is as tight and as good as it gets. There's a whole attitude toward preservation of the environment, especially Cathedral and Whitehorse. Consistently, people have come together and managed to keep these things the way they are. I'm really proud of the community, I'm proud to be part of it, I'm proud that I’m a pioneer of it. There's something about the essence of climbing right here.

Synnott: Are people taking this sport and themselves too seriously?

Barber: Think of it like tribes, there's the Iroquois, the Sioux, the Pawnee, the Cherokee--they're all Native American tribes. And it's same thing in climbing: You have boulderers, gym climbers, sport climbers, trad climbers, ice climbers, mixed climbers, alpine climbers, Himalayan climbers. They're all tribes, and if you belong to a group and it's your club, there's nothing wrong with that. Let's just make sure that all the people retain their heritage, and let's make sure that we allow these people to be themselves, and not try to make them all the same. This sport has to be different for everybody--it has to be.

Synnott: What message would you like to convey to the next generation of climbers?

Barber: I want to pass on the resource and to preserve the history of our sport. Always look at a climb in a different way, and if you have a history in an area, try to preserve that history. For example, I'm really amazed by Earl Wiggins’ first ascent of Super Crack. I might do every climb in that area with cams, but I want to do that one with hexes. The standard isn't the number grade; the standard is the style that's commensurate with the area.

In today's society, we have too many titles and too much dependence on material acquisition. And we have too many superlatives to describe what we do. We have redpoint, pinkpoint, onsight, the first this and the first that, and the 10 fastest climbs and the 10 best climbs. It’s all hierarchical and it’s all about becoming that CEO. All this one-upmanship is just not my thing. In a very simple way, you're going for a walk in a vertical world. I mean, what are you going to tell somebody about your walk? We shouldn't try to coach and describe what the rules should be. No. You should go to the bottom, then go to the top and come back down, and not leave any trash and not trample any bushes or anybody's ego, and just have a good time and not degrade the rock.

I go back to my routes and some of them have bolts in them. Superpin has three bolts in it now [Note: Barber returned in 2011 and removed the bolts]. In China, a European party put a line of bolts right next to this perfect hand crack that I'd done first ascent of seven years earlier, in 1980. What they did was they just pissed and shat on a sandbar like a bear would. They marked it--and that's just sick, for what? We're not thinking clearly. This isn't rocket science and we don't need to be known for inventing the polio vaccine. We're not Mother Theresa, we're not Gandhi, we're not Nelson Mandela. So let’s just go out and have a good time and enjoy our mates.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.