Treasure Hunters May Have Found Jesse James's Lost Gold

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

After Chad Somers saw the vision, he started digging with his bare hands. It was a half-crazy way to get Jesse James’s buried treasure, he knew, but he hadn’t brought a shovel with him that day, so he just gouged at the soft ground on the hillside. Within minutes he had clawed his way down a foot, then two.

He knew how it would look if anyone had been there to see him. People would say he’d lost his mind and laugh. And Hope would roll her eyes and say that he was off chasing another one of his obsessive dreams. But Somers was surprised at how easily the shale gave way. He wasn’t yet thinking about why that might be the case, or how it all might fit together: the old yard-sale picture, the strange carvings on nearby beech trees, the weird gold-mine legend. That would be later. For now, it was a beautiful day in the summer of 2018, and he was alone in those quiet woods, and there was only him and the oddly permeable soil.

He’d gone there that day, as he had hundreds of times before, to hike and sort things out in his mind. After roaming around for a while, he’d taken a break to smoke a cigarette on a slender ledge hard up against a huge old birch tree, situated two-thirds of the way down the steep, several-hundred-foot bluff. Somers had always noticed that tree. Its base split off into three large limbs that formed a cockeyed W, and it stood largely alone, as if it had bought out its neighbors.

Relaxing there, Somers had drifted into a kind of trance—a daydream, is the way he explains it. In the midst of this reverie, he looked over and saw Jesse James sitting next to him—the Jesse James of Old West lore, the notorious bank and train robber. Somers had been thinking a lot about James lately, and now there he was, wearing a round-brimmed duster, flicking ashes from a cigar. He said, “This is where I’m gonna bury it. This is where I’m gonna bury the biggest treasure I ever buried in my life.” Then he got up and walked off, and Somers snapped to. He could hear the creek gurgling below.

Into the breeze, he said, “This is where I’ll dig.”

Somers could never have imagined all that would follow those fistfuls of dirt: the earth-moving machinery and underground scanners; the historian who would join the cause; the rifts, both personal and geological; the way the lens on the entire saga would open wide, then narrow back down, until it once again framed only him—homeless, penniless, but ruthlessly determined—and the hole. Most of all, the hole—the cavity in the earth that would become for him a magnetic force of cosmic proportions, the nexus of his existence.

After a half hour, he’d dug down three feet, and he decided two things. The first was that he was onto something big, possibly the defining project of his life. The second was that it was time to get a shovel.

The Bowser family property was an incredible place to be a child. The spread covered more than 300 acres in east-central Ohio, encompassing a farm with hayfields and a home, barn, and bunkhouse. As a girl in the 1980s, Hope Bowser spent long and carefree days there, climbing trees, hopping rocks, picking mushrooms, and camping out. Her brothers often invited their friend Chad Somers along.

That land was divided when it was bequeathed to her generation, and Hope and one brother inherited a more than 20-acre parcel that encompasses a steep, wooded bluff over a creek. She and Chad eventually became a couple, and neither outgrew their attachment to the land. Somers in particular was drawn to it. He spent countless days roaming the property, chittering with the squirrels, watching for bobcats, listening to the wild turkeys warn off coyotes at dusk. He made a study of the trees and the contours of the landscape. “I’ve seen it flowered,” he says, “I’ve seen it flooded, I’ve seen it frozen, I’ve seen it angry, I’ve seen it calm.”

That’s the way Somers talks. His sentences come out as free verse, a sort of Rust Belt beat poetry. At 44, he has straight brown hair, a dramatically creased face, and tattooed arms. The day I meet him, he’s wearing a Chicago Medical School long-sleeve T-shirt and dirt-smeared jeans riddled with holes.

Somers dropped out of school three days into the ninth grade, partly because he had undiagnosed ADHD and couldn’t follow the lessons, and partly because he had so many chores—splitting wood, chopping hay, cutting down corn—that he would have slept through his classes even if he could focus on the schoolwork. He rarely saw his biological father, and spent large swaths of time with his grandparents, to avoid his violent stepfather. As Chad entered adolescence, his stepdad sometimes punched him in the face to assert his authority, but Somers refused to cry or, as he puts it, to “break inside.” This went on until he was 15. Somers was by then morphing into a man who had tasted enough of his own blood. But rather than give in to the urge to fight, he left.

“I’ve been burned to the ground,” he says, “and rebuilt.”

He exudes a shy charisma, but also looks haunted and wary, as if constantly engaging demons both inherited and acquired. Partly to compensate for his lack of a formal education, Somers is an obsessive autodidact. In his late teens he attended a rodeo and became fascinated with bull riding. That night he approached the announcer to ask how he might try riding; the man ignored him, but Somers eventually patched together a Western outfit, climbed onto a bull, and learned as he went. He didn’t mind absorbing lumps. “If I think I can do something,” he says, “I’ll break my back trying.” Over the next eight years he participated in events all over Ohio, until he earned membership in the International Pro Rodeo Association.

“When he gets his mind on something,” Hope Bowser says, “that’s all there is for a while.”

He eventually switched to singing and playing guitar. His grandfather taught him to play “Red River Valley,” and he worked relentlessly until he could perform at open mics and shows. He entered a countywide talent contest and made the top 10, but a legal problem caused him to miss the finals. In the midst of all this he survived an opioid addiction, a heart attack (he was diagnosed with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a condition that causes the heart to beat abnormally), and a near-fatal bout of blood poisoning.

Whenever life turned venomous, as it often seemed to, the woods were his antidote. “I always told everybody that there’s something different about this place,” Somers says. “You feel it more than you see it.”

That feeling gained new dimensions in the summer of 2018, when he and Bowser visited a yard sale. They like old stuff, and as they poked through the remnants of an attic, Bowser studied an old photograph of two mustachioed men priced at $15. There was something familiar about the portraits. “I feel like I know those people,” she said.

Somers went over and picked up the frame. “You know who these people are?” he said. They both agreed that they looked like Frank and Jesse James; Bowser recognized them from her grandmother’s old Reader’s Digest books about the Wild West.

Somers showed the portrait around, but their friends and family dismissed it. They insisted the James brothers had never been in Ohio. Somers tried to have the image authenticated, also without much luck, but one collector mentioned an interesting nugget: James the famed outlaw had also been a high-ranking member of the Knights of the Golden Circle, a quasi-military secret society that formed during the Civil War. The KGC opposed the abolitionist movement and sought to establish a new slaveholding state that encompassed the South and Mexico—and legend holds that its leaders amassed a fortune in gold and other precious metals, reportedly in hopes of funding a second Civil War. Some historians claim that KGC stashes of loot remain hidden around the country. According to Rebel Gold: One Man’s Quest to Crack the Code Behind the Secret Treasure of the Confederacy, a book by Warren Getler and Bob Brewer about the pursuit of KGC treasure, the organization had a central strategy: “to maintain a powerful, hidden base of politico-military operations in the American Deep South, no matter the outcome of the Civil War itself, and with ample treasure to finance them.”

Somers recalled hearing about a local gold mine when he was a kid. It was an alluring story that in retrospect made no sense. According to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, the only gold ever found in the state were tiny flakes that turned up in streams, having been washed down from Canada. But what if the KGC used a mining operation as a front for a project actually intended to bury gold? That’s how Somers connected the dots. “With the whole gold mine theory, what I heard as a kid, holding them photographs—it was like, I know where it is,” he says.

His grandfather had run a logging operation, and at times he’d bring young Chad along. Somers recalled a specific episode from one such outing: His grandfather was operating his knuckle boom, and Chad was watching when a woman on a porch nearby called him over. She told him to keep his eyes open, because Jesse James had buried gold there in the 1800s, and no one had found the treasure. That was right across the road from Bowser’s property.

He had to admit it sounded far-fetched that such a treasure would be there, and that he would be able to find it. “We’ve all seen Indiana Jones—who don’t want a whip and a cool-ass hat, right?” he says. “But I never had no dreams about being a treasure hunter.” Yet he needed something to put his mind to. He and Hope had just been evicted from the mobile home community they lived in, where Somers had done maintenance work in exchange for rent.

His James theory consumed him. “Hope was like, ‘Oh geez, shut up about Jesse—not everything’s the Jesse James site,’” he recalls. “I think I drove her about half nuts with it.”

Bowser was skeptical, but also curious. “[Chad] thinks differently than most people,” she says. “He sees things that other people look at and don’t see.”

Either way, he figured he would find out for himself. Soon after purchasing the yard sale photograph, Somers had his vision and returned to the woods with a shovel. Within a day or so the hole was more than six feet deep, so he brought in an extension ladder and a generator to run a light down there. At around 10 feet down, he was too deep to toss out the dirt, so he fetched a five-gallon bucket that he tied by rope to a root at the tree’s base. When the bucket was full, he climbed out, hauled it up, and dumped it. “Repeat process several times until said desired depth is reached,” he says with a grin.

Using this grindingly slow method, he reached 15 feet, then 20. After a month, he maxed out the 25-foot extension ladder. He found artifacts, including an old harmonica reed and a cigar butt made from a single leaf of tobacco—both suggestive that someone had been there, perhaps many decades ago.

Occasionally friends came by offering help, then peered into the hole and remembered they had something else to do. Bowser fretted that it might cave in. She asked him not to mention his project socially; people in town ridiculed the undertaking. “He’s like, ‘I dug a hole 30 feet in the ground, and I’m standing on a vault of Jesse James’s gold,’” she says. “People are like, ‘Oh yeah, sure.’”

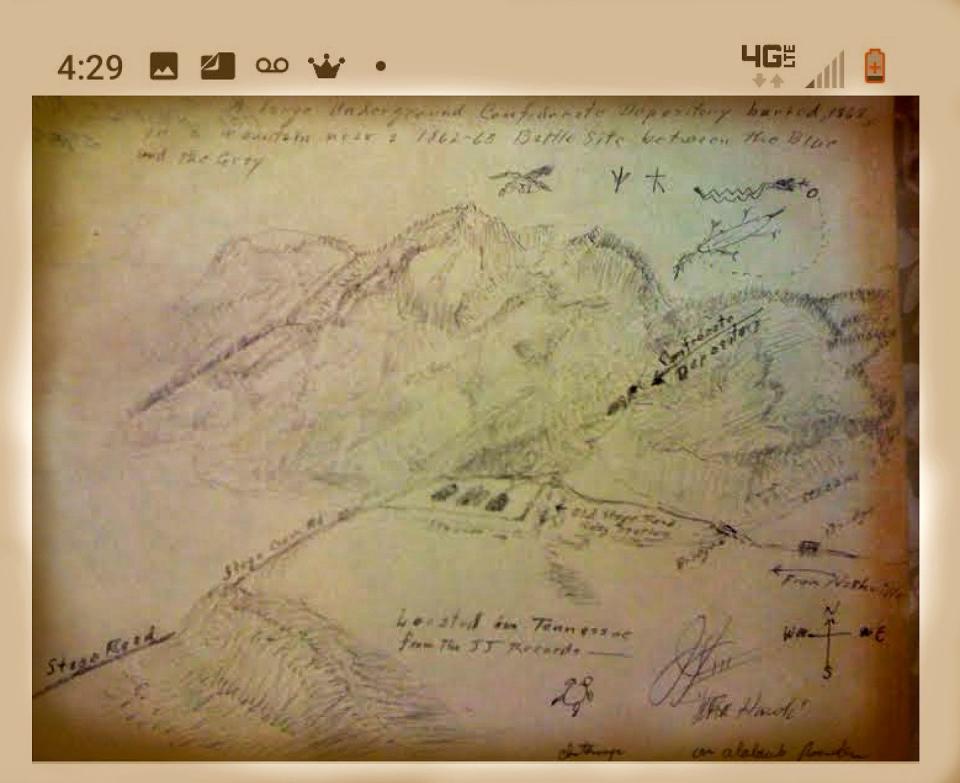

But he kept finding intriguing clues. Online, he located a hand-drawn map of unknown provenance that claims to identify the location of a large underground Confederate depository in Tennessee on “an 1862–63 Battle Site.” But Somers observed that the lettering of the world “Battle” was written in a way that it could be read as “13 oHio”—the 13 perhaps referring to nearby Ohio Route 13 or a KGC symbol. And when Somers turned it to a north-south orientation, the notation “From Nashville” could appear to refer to nearby Zanesville. Somers pulled up a Google Earth image of Bowser’s property and laid it alongside the map: The way the features of the landscape form the shape of the letter J was a precise match. Some of the map’s symbols even aligned with what Somers had seen on the trees, including a turtle, a wolf, and the letters “JJ.”

When he showed this to Bowser, she was stunned. “It was kind of undeniable after that,” she says.

Somers had another tool in his arsenal: a copy of Rebel Gold. As he searched the woods, he found symbols on the trees—hearts, turkey tracks, turtles—that were identical to the ones described by the authors. “I used it like a Bible,” Somers says. “I carried it out in the field with me.”

He was 30 feet down in the hole when his shovel gave off a metallic ting. Somers struck a smooth, hard, bluish-gray surface. It appeared to be the top of a vault, but he couldn’t penetrate it—every drill bit he tried became stuck.

Before he figured out what do to next, life intervened. He and Bowser were hired to remodel homes in Columbus, an hour away. They relocated into the motels and properties they were fixing up, to be closer to the work, and Somers barely saw the hole for a year. They needed the money, so the job was helpful. But “every day,” he says, “I was thinking about it.” And he had no idea when he would make it back.

My first morning in Ohio, Warren Getler drives to the Bowser property in a mud-spattered rented Jeep. It’s mid-March 2022, and he’s come out for a week in hopes of identifying and recovering what he believes could be KGC gold. Today, he is planning to oversee a ground scan using geophysics equipment, to try to zero in further on the potential treasure. The forecast calls for an unseasonably warm day.

Getler is a journalist, geophysics enthusiast, and longtime student of KGC history, having coauthored Rebel Gold. He’s investigated several sites purportedly connected to the Confederate organization, including one on public land in Pennsylvania where, Getler says, the FBI was allowed by a federal court to dig, largely based on his research. Somers’s site is different. It’s on private property, which means no interference from government agencies. The hope is that after tests confirm something is there, a crew will commence to “dig shit up.” For help, he has summoned his friend Brad Richards, a history teacher whose expertise in 19th century America helped him land a role on the History Channel show The Curse of Civil War Gold, which spanned two seasons. Richards has driven in from Michigan with his 16-year-old son, Bradley.

Wearing a windbreaker and a fraying baseball cap bearing the word WOOF, Getler is a kinetic and youthful man of 61, with a tuft of brown hair. As in his appearances on TV shows, including a guest-star turn alongside Richards on The Curse of Civil War Gold, he’s intense and excitable—a geyser of detailed explanations filled with rhetorical questions for which he instantly provides answers. At one point, in the course of explaining why he isn’t using an underground detection tool called a gravimeter, he offers backstory about another dig. “Well, a gravimeter in this situation—what is the situation?” he continues. “What are we working with in terms of the stratigraphy or the geology? You know what it is—sandstone and shale.”

As a child growing up in metro Washington, D.C., Getler became fascinated with fossils he plucked from streams and the woods. When he was 12 and riding the bus as a member of the Annandale, Virginia, travel soccer team, he scanned the sedimentary cliffs of Pennsylvania and Upstate New York and lobbied for bathroom breaks where he believed he might find trilobites. Teammates called him “Professor Brachiopod.” Once, during halftime at a playoff game in Ohio, he walked down to a stream and discovered several fossils; he became so absorbed looking for more that he missed the second half.

After graduating from Princeton, Getler worked for the likes of the International Herald Tribune and Wall Street Journal. But he kept at his hobby; his collections of fossils and dinosaur bones grew to the point that classes of schoolchildren came for tours. A duck-billed dinosaur adorned his townhouse window; he displayed a T-rex jaw in his living room and an ichthyosaurus on his mantel. At an auction, he met the principals of Witten Technologies, a geophysics firm developing ground-penetrating imaging radar. Getler eventually took a job there.

In the 1990s he met Bob Brewer, an Arkansas man who’d spent decades searching for KGC treasure. Brewer had decoded the organization’s maps and ciphers to the point where, over the course of numerous hunts, he’d dug up about $200,000 worth of gold and silver coins. Rebel Gold, published by Simon & Schuster in 2003, led to Getler scoring a consultant role on the blockbuster film National Treasure: Book of Secrets. His profile elevated, Getler became a kind of consigliere to a small but lively segment of the treasure-hunting community focused on the KGC. Spurred on by his appearances on X-marks-the-spot reality shows, hopefuls with metal detectors regularly seek him out for guidance.

The drive follows several miles of twisting pavement past tumbledown barns and front lawns doubling as auto graveyards. The blacktop eventually gives way to gravel; we pass a ROAD CLOSED sign and climb a steep dirt pitch before pulling into a field. The last half mile is on foot, past lowing cows and lagoons of mud. As we descend a wooded slope, Getler opines that James chose the site for its many helpful attributes: a creek for water, long-living beech trees to bear carved clues, a nearby stagecoach station. From the bluff, he could maintain a lookout for unwanted attention.

Getler leads us to a series of beech trees Somers had identified while roaming the land. He contends that they provide a series of clues—a “story in code”—of James’s activities there. They include an image of a man’s head, which Getler says is both James’s self-portrait and a rudimentary blueprint of the tunnel system, about 100 yards away, where the treasure lies. “There’s a deeper chamber,” he says. “You see it? The rectangle here? That’s our hit.”

Still other trees show rabbits, turkey tracks, hearts, and more. On his first visit several months earlier, Getler saw a faint inscription near the bottom of one tree that, to his eye, reads “Jessie W. James” and the year 1882. “I actually cried,” he says of finding the inscription. “I was trembling.”

Getler contends that this was James’s way of indicating that he didn’t die in 1882 at the hand of Robert Ford, as recorded in history books, but instead faked his death to secretly carry out missions—one of which was burying gold in a hillside in Ohio. “He’s so creative and ingenious,” Getler says.

There will be other clues in the vast, complex, mathematically rigorous system the KGC invented, Getler says. The key, he adds, is pattern recognition—the symbols found here match imagery found in other parts of the country, such as Arkansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, and KGC records he viewed in the National Archives. “If you have the same symbology appearing—this kind of gets into Da Vinci Code stuff, right?” he says. “Then you might be onto something.”

We head to the top of the bluff, where Brad and Bradley Richards are waiting. Bradley straps into a fixed rope for safety on what his father calls the “very, very difficult terrain” of the steep bluff, and begins scanning a 6-by-18-foot grid above the W tree. He uses a Whites TM 808 two-box metal detector, capable of searching for large metallic objects 20 feet underground. That, in turn, is connected to an Arc-Geo Logger, a device that converts the metal detector’s sounds into a heat map that depicts the rough size and shape of a target.

That afternoon, they study the results: a rectangular blob on the Arc-Geo Logger screen that appears to lie 10 to 12 feet below the surface. Richards estimates it’s about eight feet wide and three feet deep, to which Getler barks, “Holy shit!” At that size, he says, doing quick math, the cache could weigh 7 to 9 tons.

There’s no guarantee it’s gold, Richards points out. “But it’s showing metal,” he says.

“And it’s showing it in the place where the ‘Jesse map’ is showing it,” Getler adds.

The group rules out other possibilities: There are no naturally occurring metals here, and it’s an unlikely location to bury scrap. They also speculate that the soft ground and clearing below the tree may be clues—they suggest a prior excavation.

Somers stops by to look at the image, and fist-bumps the others. “It sure beats digging a hole 30 feet in the ground on a whim,” he says.

Life’s inflection points can be tough to pass judgment on at first. A new job can seem like a step forward, but morph into disappointment. Getting dumped from a relationship can be heartbreaking, but ultimately lead to a better match. So maybe it’s too early to categorize what befell Somers and Bowser in autumn 2021. They were rehabbing properties in Columbus; the boss owed them thousands, but kept saying he would make good on the next job. Then he abruptly stopped calling, and stiffed them. Somers lost his tools and they had to forfeit a couple of storage units’ worth of possessions when they couldn’t pay the rent.

The only upside when they scuffled back home was that Somers again had time for his Jesse James project. When he finally returned to the dig site, he found his hole partially collapsed. Rocks pelted him when he clambered down, and the entire enterprise felt far sketchier than he’d left it. Bowser wanted him to stay out of the hole. But Somers, with little else to occupy his obsessive mind, struggled to stay away. “It was driving me insane,” he says. “Like, everything was about the hole.”

Bowser was worried that Somers was setting himself up for another huge disappointment. “I tried to keep him levelheaded about it,” she says. “I hate when he gets sad about stuff.”

On one of his last forays down the hole, Somers noticed something: A few rocks had shifted, revealing an opening. It appeared to be a shaft leading into the hillside. He was pondering his next move when he happened to watch an episode of Beyond Oak Island, a History Channel show about lost treasure that featured Getler. Somers decided to reach out. “We need to have a conversation concerning certain KGC maps and what I have discovered here,” he wrote on Facebook Messenger. “Like a concrete vault 30 feet in the ground marked by a giant arrow at the bottom of a giant J where an alleged gold mine once was. Sound interesting enough for you?”

He continued: “If you want the story exclusive we can talk… I’m about to show the world the end of a 200-year-old treasure hunt.”

When Getler called an hour later, his first question was: “How far are you from Zanesville?” His book had documented a Zanesville connection with James.

“I’m about 15 miles away, Mr. Getler,” Somers said.

“Call me Warren,” Getler replied, “and I’m coming.”

They began talking regularly, and Getler made the trip to Ohio about two months after that first conversation.

More evidence of an Ohio-James link turned up in about 20 letters from the likes of Jesse James III, also known as Orvus Lee Howk. One 1948 missive mentions Zanesville and “your look-out at W”—a reference, they believe, to the W tree. In another letter, in December 1948, Howk wrote, “I do know that we are on the right track at W.”

There were also newspaper articles from the Zanesville Signal. In 1948, the paper reported that “local kinfolk claimed that Jesse James had once lived here.” The following year, the Signal trumpeted a bigger story: A cadre of James’s relatives, including Howk and Roscoe James, Jesse’s nephew, had converged on the area looking for treasure. According to the story, James had gone to Ohio in 1882, after faking his death, and roamed the countryside as J. Frank Dalton, a lightning rod salesman. According to this legend, he lived to be over 100 years old. “The old fellow who claims to be Jesse James has supplied his friends here with a map which is supposed to lead them to a spot, near Zanesville, where he buried one and one-half million dollars’ worth of gold bullion,” the story says. The team recovered only an empty metal box, but reported locating “many strange-looking marks on tree trunks…just where Jesse said we’d find them.”

Still, some historians cast doubt on this array of circumstantial evidence, and suggest that the enduring lore of buried KGC treasure has little basis in documented fact. They point, most obviously, to the absence of any major James-KGC stash despite the decades of hunting. In fact, T.J. Stiles, a historian author of the seminal biography Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War, says that while it’s true the outlaw was deeply involved in the Confederate movement, he uncovered no evidence that James had been in Ohio. “It’s not impossible,” Stiles says, “but it would have been a rarity, nothing that would suggest he might make the effort to stash valuables there. He strongly identified as a Missourian and a Southerner.”

Notwithstanding his mythical place in popular history and the team’s fascination with him, James is a troubling figure: a murderer, terrorist, and white supremacist from a slave-owning family who fought and killed in an effort to prevent emancipation. And James liked to spend his money, not save it, Stiles says. “I found absolutely no evidence,” he says, “that Jesse James buried treasure.”

None of this skepticism has kicked dirt over the enduring torch that multiple generations of treasure hunters have carried for KGC and James-related treasure—Getler and Somers serving as prima facie evidence of this phenomenon.

“He was excited, and it really got me excited,” Somers says. Propelled forward by their conjoined energy, they navigated out of raging currents of cynicism into eddies of credulousness. True, Somers had done things backwards—he’d dug a hole first, then investigated—but none of it seemed to matter. During that first visit, Getler along with Brad and Bradley Richards took readings—though on less-sophisticated equipment than the TM 808—that confirmed the presence of something underground at the dig spot.

Even when the others left, Somers lingered over the hole. Eager to probe farther, Somers attached a camera to an industrial endoscope—a snake-type device that utility crews use to inspect sewer lines. He hunkered at the edge of the shaft, working to manipulate the device inside; Bowser perched at the base of the tree, hunched over a monitor, watching the feed and calling down instructions.

This method harvested images that were blotchy and grainy, but intriguing. They showed what appeared to be manmade walls, and a glimpse of something bright and yellow and reflective.

The hike to the W tree from atop the bluff consists of a harrowing descent of a few hundred feet down a 75-degree slope. It’s daunting enough that Somers put in fixed ropes.

A small group of us—there are two photographers, a videographer, and another reporter on hand—slide down and sit propped up by trees, only to watch Somers gallop down. All this vertiginous navigation raises a key question: How will the 6,800-pound Takeuchi mini-excavator that Getler has hired for the project navigate such a slope? Eventually, Hans Stockli hikes down the slope to provide an answer. He is Hope’s ex-husband, a former neighbor, and the friend of Matt Sheets, who owns the excavator in question. “Are you crazy enough to get an excavator in here?” Getler asks.

Stockli replies, “My buddy Matt is.”

They decide that Sheets will make an angular descent, transecting the hillside. He’ll cut a diagonal path, building an embankment on the downhill side as he goes. That afternoon Sheets makes about 50 yards of progress, about a third of the distance he’ll need to cover.

As we wait, Bowser takes us to meet Levina Nethers, 86, a lifelong area resident. She recalls being told that her husband’s great-great-grandmother provided Jesse James with meals and laundry services when he passed through the area. One day, she informed Jesse that she was facing bankruptcy. “She told him that [the bank] was gonna foreclose on her farm the next day, and she wouldn’t be there,” Nethers says.

“And he said, ‘Don’t worry about it, I’ll take care of it.’… He came back the next morning and had the money for her foreclosure.” She paid off the loan, Nethers says, and the next day, the bank was robbed.

That evening, I ask Getler if he feels a growing sense of anticipation, and he cuts me off midquestion. After 25 years of pursuing KGC history, trying to prove that he’s right, he says, this would be sweet validation, and a career capstone. “Of course I do,” he says. “Do you know how weird it is? Do you know how powerful it is right now?” He holds out a trembling hand.

I ask him what he’ll do first if they find treasure. “Cry,” he replies. “I’ll break down, man. It’s too powerful.”

But the next two days bring scant progress. Sheets makes gradual headway, plowing down saplings and laying them down along the embankment on the downhill side to create a kind of earthen guardrail. Stockli darts in with a chainsaw to clear branches and brush. The slope is denser with roots and topsoil than they’d expected.

Halfway through the third day—scheduled to be my last on site—they have yet to turn the corner toward the W tree. Stockli’s chainsaw gets stuck, and there is a delay involving the excavator’s hydraulic line.

Each setback subtly ramps up the tension. It’s not as if there’s any hurry—whatever’s in the ground has been there for a long time—but this is not an open-ended enterprise. Getler, who is circumspect about how much he’s spending on the project, doesn’t have an unlimited budget. And he took a gamble by inviting a group of journalists along, but he and Brad and Bradley Richards and the work crew have lives, jobs, school to turn back to.

The project is remarkable for its scrappy, homespun approach. But the flip side of that is a real scarcity of resources. There is no government or foundation underwriting a safe, systematic excavation. If Somers and Getler don’t get deep enough into the ground this week, it’s not clear what will happen next.

Occam’s razor is a problem-solving principle that dates back to medieval times. The idea is simple: If you’re trying to sort through competing hypotheses, you’re better off choosing the one with the fewest assumptions. The most straightforward explanation is preferable to one that’s more complicated. Simple theories are easier to validate.

Adherents to this principle would look askance at Somers’s and Getler’s Jesse James theories. The simplest explanation for what’s found in Bowser’s woods is that some bored or love-crazed teenagers carved images on the trees. The newspaper stories could be written off as reporters airing out local gossip on slow news days. If James indeed died in 1882, as was widely reported, there would have been no Ohio treasure-stashing adventure.

Much of what Somers and Getler say about the site comes with heaping doses of supposition—educated guess stacked on hypothesis piled on extrapolation, all of it bracketed by fervent conviction. Wrapping your head around the totality of their case is an isometric mental exercise that creates a sinewy strain between faith and fact.

On one tree, for example, Getler points to the simple etching of a face under a hat. Not only does he argue that this is a KGC marking—“a rebel portrait of Jesse and the hat”—he says it signifies more than it appears to. “It’s not a coincidence,” he says. “That hat is a shaft.”

Getler openly confesses that nothing is certain, and is acutely aware that few people will take any of this seriously until and unless they uncover KGC treasure. “I hope it’s there,” he tells me in one candid moment, “because this is a bunch of crap otherwise.”

But on many other occasions, he whips himself into a state of ecstatic certainty, repeating over and over the various clues they’ve uncovered as if fingering rosary beads. Then he adds, “I know what I’m talking about, because when I know things, I know them,” he says, tautologically. “… I know things that would rock the fucking world if I revealed [them].”

The more of a true believer Getler becomes, the more I wonder why he feels the need to exude such evangelistic vehemence. It’s almost as if willing me to believe will make him right. He peppers in implausible claims about the site’s significance. “It’s getting to the point where it’s as curious and intriguing and as amazing as finding something on the Giza Plateau in Egypt”—home of the Great Pyramids—“as far as American history goes,” he says. (Somers compares the site to King Tut’s tomb.) Other times Getler draws parallels to the Antarctic expedition that located Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance shipwreck after 106 years in March 2022. But he adds that undersea wrecks are relatively easy to find—the people hunting them often have navigational plotting to follow.

Independently verifying their claims is a tricky proposition. Take the W tree. Birches can live for more than 300 years, but is that particular specimen old enough to have lorded over a James-led treasure burial? Mark Webber, a master arborist based in Dayton, Ohio, says that answering that question accurately would require drilling into the tree to extract a core sample, among other steps. Some really big trees are not as old as you think due to shade, soil quality, and drought or floods, he says.

Adding to the festering sense of uncertainty about the enterprise is the principal characters’ embrace of the supernatural. Bowser says she descended the ladder once, and felt so rattled by a dark chill that she had to immediately climb back out. “It was too much,” she says.

Getler suggests the reason is that the hole is a source of paranormal activity. The first time he was alone at the site, he says, it exerted a strange pull over him. “Something possessed me,” he recalls, “and I felt I was going to let go and fall into the pit.”

After hours in the hole, Somers says he saw the walls moving—vibrating. “I’m thinking, I’m too deep,” he says. “I gotta get outta here. I’m seeing stuff.” Gold is a strong conductor, and he theorizes that it may have been reacting to Earth’s electromagnetic field.

There were other strange and unexplained occurrences. A coyote once approached Somers and ignored his attempts to scare it off. He finally had to fire his .22 overhead to make it skitter away. Another time, a pack of coyotes surrounded his truck when he and Bowser were sitting inside; they dissolved into the night after the couple had a look at the ghostly glow of their eyes. “There is a supernatural element to all this,” Getler says. “If you read about this stuff, you’ll hear that these treasures are protected by spirits.”

Then there’s the origin story of Somers’s daydream, which led him to believe that this is his life’s mission. “I don’t feel like I found this thing,” he says. “I feel like I was led to it. Like, I asked for help and got it from I don’t know where… It doesn’t make no sense. But I’m glad.”

The sheer mass of circumstantial evidence, combined with their fiercely dogmatic beliefs, has a generative power, inspiring enough of a sense of possibility that I postpone my flight home to spend an extra day at the dig.

After three days, Sheets maneuvers the excavator into position. It’s early evening, and Getler announces that they’ll finally dig in the morning. Bowser heads off to deal with car issues, and Getler makes dinner plans. I walk the half mile back to my car, hoping for an early start.

From that excruciatingly enticing moment, though, nothing goes as planned. Back where we parked, photographer Maddie McGarvey receives a text that the excavation has started—apparently they decided not to wait. We hustle back to find Getler standing on the slope about 15 feet above the site, watching intently as Sheets lifts away bucketfuls of dirt.

Getler says he was surprised, too—he was packing up when he heard the heavy equipment and hurried back. Sheets is already about five feet down; Somers is kneeling, studying the hole, sometimes jumping down inside to inspect the progress.

Despite the abruptness of the moment—liftoff coming unannounced after days of runway taxiing—Getler is ecstatic. “Hans was standing at the tip of the opening,” he says. “And Hans says, ‘I can see in there—it might be a tunnel.’ I go, ‘Yes, yes, yes!’… If he confirms a tunnel, I’m gonna give you a hug, man.”

Getler says that now that the process is underway, he’s not going anywhere. “I’ll tell you what, Chad’s not leaving,” he says. “He’ll stay here all night. I’ll stay here all night.”

But moments later, two of Bowser’s siblings arrive to question the excavation and ask that the project come to a halt until they can clarify whether Hope’s brother, the co-owner of the land, has signed off on the dig. Everyone calls it a night to let the family sort it out.

Somers reveals that just before the work stopped, he glimpsed through the wall of the freshly dug hole a hallway with what looked like walls and a ceiling: the tunnel that Getler was so keenly hoping for. But even if the family matter is resolved quickly, definitive answers about the site will have to wait. Brad Richards has to head home—his son has already returned to school—and Getler is leaving tomorrow.

Over the next few months, the project ticks slowly forward. In April, with the Bowser family issues resolved, Getler hires an Ohio firm to run a test on the site using the Sensors & Software Noggin SmartCart system, which examines sites using ground-penetrating radar that scans for voids and buried metal objects. The GPR detects a cache of possible metal that measures 14 feet in length and four feet in width.

In May, Getler recruits a television production company to shoot footage on site, with the goal of pitching a show. He and Brad Richards return, along with Tim Williams, the inventor of the Arc-Geo Logger and a veteran of past KGC searches. Williams tells me the data from various technology reinforces the idea that Somers might have made a significant find. “There’s definitely something right there,” he says.

On that visit, Sheets excavates a second, 15-foot hole next to the first, still a few feet short of the exact location shown on various devices.

The only person who doesn’t depart after each of these incursions is Chad Somers, who remains more fixated than ever on the hole. Armed with a shovel, he pushes onward and downward, probing until, about 20 feet down, he finds several openings into what appear to be more tunnels. Getler and others ask him not to risk exploring these crevices, but Somers can’t help himself. He slips into one passageway and crawls about

50 feet before exiting an opening in the hole that had been dug back in March.

During these forays he takes grainy photographs with the snake cam and collects a couple of artifacts: a .38 Special bullet, which could date back to the 1920s, and a bone fragment. He captures images of what appear to be metal urns, a whiskey barrel, and a bracelet, and identifies what Getler—relying on Somers’s photos—calls a “fricking huge vault chamber.”

He also spots what may be gold. “There’s one picture… where there are six [gold] bars in a row,” Getler says—or, as he clarifies, “beautiful gold bar–looking things.” He later adds, “I’m either right on with my analysis, or I’m crazy.”

Somers says his unscientific analysis from probing and crawling around the site indicates the presence of three underground pyramids on that hillside. He has also found doorways sealed off by manmade blocks. All of this is alluring, but Somers alone, with no heavy equipment, can hardly push much deeper.

In fact, the enormity of the task, and questions over how to proceed, become a point of conflict. Bowser returns to renovation work so they’ll have some income, but the couple’s relationship becomes strained, in part because Somers would rather chew on aluminum foil than trade in his quest for painting walls or stocking shelves. “This is my job,” he says.

Later, he adds, “I’m tired of people telling me that I gotta do more, and suffer more, to reach the goal that seems to elude me.”

Somers is adamant about this approach no matter how dire his situa-tion gets—and during this time, the particulars of his life will become quite dire. His truck breaks down, is impounded, and will cost $2,500 to recover—money he doesn’t have. He moves his few remaining possessions to his grandmother’s house, and for a time lives in the crude tarp shelter that he and Bowser erected at the top of the dig site. For a couple of weeks he is stranded there with no vehicle and no data on his phone. He sells off some possessions to stay afloat, and for a time stays with a friend about 10 miles from the dig site.

“At the age of 43 [now 44], here I sit,” he says. “Homeless, no vehicle, in worse shape now than I was when this project started.”

Even more alarming, Somers has responded to the feel of the wall on his back by pushing everyone else away. Somers has lashed out at Getler repeatedly, over an array of issues; he believes that Getler has at times taken credit for his discoveries and exerted undue control over the project. For months, they were locked in a disagreement over a fee they were paid by the TV production company. Most of all, Somers chafes that Getler is choosing a conventional livelihood over working in the dirt alongside him, saying that he lacks “the grit or the determination or—let me put it plainly—the hunger.”

Getler, though, says he has invested plenty of himself into the project, including thousands of dollars both on the excavation work and keeping Somers afloat. In his ferocious dedication to proving his version of history, he’s equally obsessive. He sounds like someone doing his best to cling to the project’s curves as it careens into ever more uncertain territory. The possibility of finding treasure makes it worth the calculated risk, he says. “This would be absolutely historic, beyond anything you’ve seen in your life.”

But he refers to Somers’s mindset as “fanatical” and calls him “stubborn” and “not rational or reasonable.” And he worries that Chad will venture into the hole one time too many and get himself trapped in there, literally or metaphorically—Ahab consumed, finally, fatefully, by his white whale.

By late summer, the rhetoric cools, and the principals agree that Somers will stay above ground while Getler looks for a funding source—ideally a TV project that will both underwrite and chronicle the rest of the dig. And in late 2022, Somers and Getler signed on with Mark Wahlberg’s production company to pitch a television series. That blows some wind into their sails, but it won’t deliver any game-changing infusion of cash unless and until a network or streamer like Netflix agrees to fund it.

Through all of this, Somers remains fixated on the hole. He describes the situation as being “in limbo,” clearly referring to both his hole and his life, because they’ve become almost interchangeable. Given the unknowns, it’s hard for some to comprehend his mulish-ness. Why not just get a job for $18 an hour, have a roof overhead, and visit the site on weekends and evenings until financing is in place?

Not Chad. This started with a hole he dug by hand, and there is a terrible beauty in the purity and all-consuming nature of his quest. Of course it makes more sense to get a job, to take the safe and prescribed approach. But what has that ever done for him? He’s been beaten down, grifted, laughed at.

Once, hanging out on top of the bluff, I ask what it would mean to him to find Jessie James’s buried treasure. Somers is deeply self-deprecating, but he is also prideful. He says there are people who use money to build towering shrines to their own selfishness, and there are others who “never had nothing and they end up with something, and usually by the end of it they have nothing again because they helped everybody that’s ever helped them, or that they cared about. I mean, if I die with even $2 in my pocket, I did something wrong. I think that that’s what I’m supposed to do.”

But he doesn’t stop there. For all his backwoods eloquence, it’s not hard to detect the heavily worn shoulder chip of a man who has something to prove. “I wanna just write my name in that book,” he says. “That one that people look at and go, ‘This dude did something really important.’ And I guess that’s probably what means the most.”

Money matters. Of course it does. Finding a cache of lost gold would put so many worries to rest. But for Somers, it would still be the second most important thing.

Something is down there. There’s too much scientific evidence now in place to deny it. And the truth about what lies inside that Ohio hillside will emerge, maybe later this year. Until then, Somers will suppress his urge to claw deeper into the earth. But in every other meaningful way, he’ll remain down in that hole until the last shovelful of dirt has been turned over.

You Might Also Like