How 'Transitional Objects' Can Help Us Process Grief

A worn-in sweatshirt, heirloom jewelry, or even a discontinued Victoria’s Secret body spray can help us cope with the loss of a loved one — and keep their memory alive.

After her mom died, Austin D'Anna, a 27-year-old sales manager in Columbus, Ohio, was sorting through her belongings when she came across her mom's wedding band (it had been put on a keychain after her parents' divorce). D'Anna immediately put on the gold band, which was made from melted gold from D'Anna's maternal grandmother's jewelry, and wore it every day for the next three years.

"I swore that that ring acted as my 'guardian angel.' I can't explain it, but I felt infinitely more safe, lucky, prosperous, etc. once I started wearing that ring … The ring gave me peace. All I had to do was look down at my hand and I knew she was there, helping through my latest quarrel, interview, audition," says D'Anna.

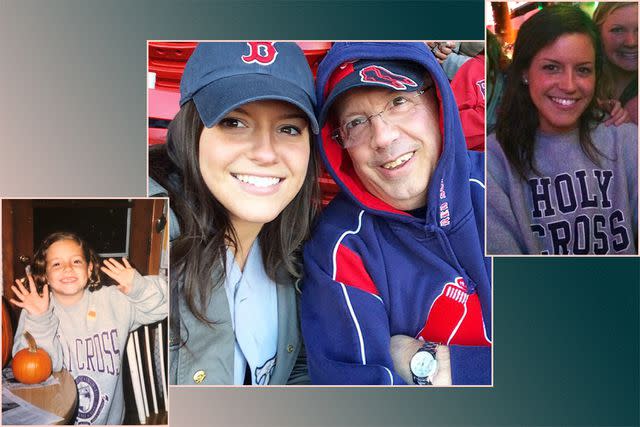

Laura Madaio, 31, a marketing executive in South Boston, Massachusetts, and founder of Grief Hungry, a social media space for grievers to share their loved ones' recipes, always wore her dad's clothes. But after he died in 2018, putting on his Western New England University sweatshirt (her alma mater) that he wore to her field hockey and softball games and his old Holy Cross sweatshirt (his alma mater) took on a different meaning.

"I can vividly picture him in all of the items. Maybe that's partly why they're so special to me. They make my memories feel more real. They make him feel more real now that he's gone," Madaio says. Plus, she adds, his worn-in sweatshirt has the "distressed look that people pay extra for nowadays."

"I can vividly picture him in all the items. Maybe that's partly why they're so special to me. They make my memories feel more real. They make him feel more real now that he's gone."

Christina Wilson, a 44-year-old life coach in College Station, Texas, lost her best friend, Teresa, in 2015. Every year on Teresa's birthday, Wilson sprays "Scandalous," a discontinued Victoria's Secret body spray that was Teresa's favorite. "It just makes me feel close to her and that she's really not that far away. It's comforting to access her memory that way," says Wilson.

I can relate. Since my mother died of ALS 12 years ago and my father from cancer eight years ago, I love to keep their belongings close. I still cherish my mother's diamond earrings for a special occasion, her brown fake Gucci purse, my father's sweat stained tennis T-shirt, and his 11-year-old green Jeep that I inherited. (Because of my connection to my dad through the Jeep, I immediately empathized with Minnie Driver's character's love for her late husband's car in this Modern Love episode adapted from the New York Times column.) My parents missed most major events in my adult years — my wedding, buying my first house, and the birth of my daughters. Keeping their belongings close does not bring them back, but it has made those moments feel a little less lonely without them.

When someone dies, items that they used can become an important source of connection and comfort for their loved ones. "[These items] are important because they provide a sense of security. They are symbolic connections. It's a tangible way of being connected and feeling closer to the person you lost — and, in all honesty, helping us transition to living without them," says Cara Mearns-Thompson, a licensed clinical social worker focused on grief and co-founder of the Grief Club of Minnesota.

Some experts refer to these objects as "transitional objects of grief." In 1953, Donald Winnicott proposed that "transitional objects," like a stuffed animal or blanket, helped young children navigate separation from their caretaker. Similarly, objects chosen after a loved one has died can support a bereaved individual transition through the separation of death. These objects, which other experts refer to as "linking objects" are a physical reminder for a grieving person of a loved one who died. According to grief experts, these items are common among grievers. Almost all of 294 bereaved mothers in one study who lost their children to Sudden Infant Syndrome (SIDS) reported that they had a transitional object of grief, such as their child's blanket or favorite toy.

: I'm a Psychiatrist and Yellowjackets Is One of the Best Portrayals of Trauma I've Seen On TV

Once you start looking, you can find examples of them everywhere in pop culture, too. Nadia's dead mother's necklace in Russian Doll, Devi's father's motorbike in Never Have I Ever and some food items in The Bear (which I won't share for fear of giving away the ending) are just a few.

"It's instinctual to reach for linking objects after a person precious to us dies. We miss someone, so we reach for the closest alternative," Alan Wolfelt, Ph.D., a grief counselor, author and founder of the Center for Loss and Life Transition,says. "In addition to missing their body, their face, their smile, we miss their voice, their laughter, their scent, their touch. Linking objects are tangible, so they connect us through touch and often smell as well as sight."

"It's instinctual to reach for linking objects after a person precious to us dies. We miss someone, so we reach for the closest alternative. Linking objects are tangible, so they connect us through touch and smell as well as sight."

Grief experts view these objects as a healthy coping mechanism in the grieving process, which can help bereaved individuals transition to life without their loved one physically alive while maintaining a loving connection with the person. According to Mearns-Thompson, it's natural to fear that our loved ones will be forgotten after they die, and these selected objects often serve as reminders of their life to assuage that worry.

"When you think about transitional objects you can think about us carrying them with us both literally and figuratively. And that healthy grief is creating a new relationship with the deceased which can happen through these transitional objects as well as sustaining a loving connection with that person who died," says Mearns-Thompson.

These momentos can also serve as a narrative prompt according to Robert Neimeyer, Ph.D., the director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition and professor of psychology at the University of Memphis. "They provide the opportunity to speak the loved ones' name, to tell a bit of their story once more," he said. "When we share a story about another, we invite them back into life. We renew their membership in the club of life. We 'remember' them in this way."

It's another reason why Madaio loves wearing her dad's clothes. "It's always a little special for me when someone compliments me on something I'm wearing, and I get to say 'Thank you! It's my Dad's.' Maybe, subconsciously, I hope people do ask," she says.

Some may feel less inclined to touch or use these objects as time passes, which can be a sign of healing and reconciliation, according to Wolfelt. Depending on the person, object, and relationship with the deceased, some may continue to use or wear their objects frequently, even decades later. I go through different phases where I cling to one object of my parents more, but I always feel better with one of their belongings close by. As I write this I'm sitting at my father's desk and feel encouraged by him in some small way.

"I don't see any problem in people wearing their mother's engagement ring or something for the rest of their lives or having a special broach that represents their grandmother or keeping their dad's carved decoy on the library shelf," says Neimeyer. "These are perfectly normal, touching, interesting ways that we remind ourselves and others that our lives had significance because of these relationships. We carry these people forward in our lives."

: Why Celebrities Are Turning to EMDR Therapy for Their Mental Health

There are some objects, like my dad's car, which unfortunately can't be held onto forever. Parting with one of these objects can be difficult, but, as Mearns-Thompson helps remind me, the memories associated with the object can't ever be taken away. And of course, grief objects are just one of many coping mechanisms you can turn to, she says. Other ways to hold space for a loved one who has died include honoring the person on a special holiday or with memorial markers, such as trees, supporting causes associated with that person's death, and enjoying activities you both shared together, such as music or food.

Understanding the special power of these objects, D'Anna recently parted with the gold wedding band that brought her so much peace after her mom died. Before getting married last year, she had the band re-polished and engraved with "Dawn's Girl" (their mother's name) and gave it to her little sister as a maid of honor gift, she says. "She's the only person I'd stop wearing it for."

"Grief is hard. When I reflect on my mom's passing, I realize I'm not as okay as I usually think I am. Nothing prepares you for this feeling, or how to cope afterwards," she continues. "But for those of us who are lucky enough to have items of loved ones that have passed on, it's something to keep us connected. For that I'm grateful."