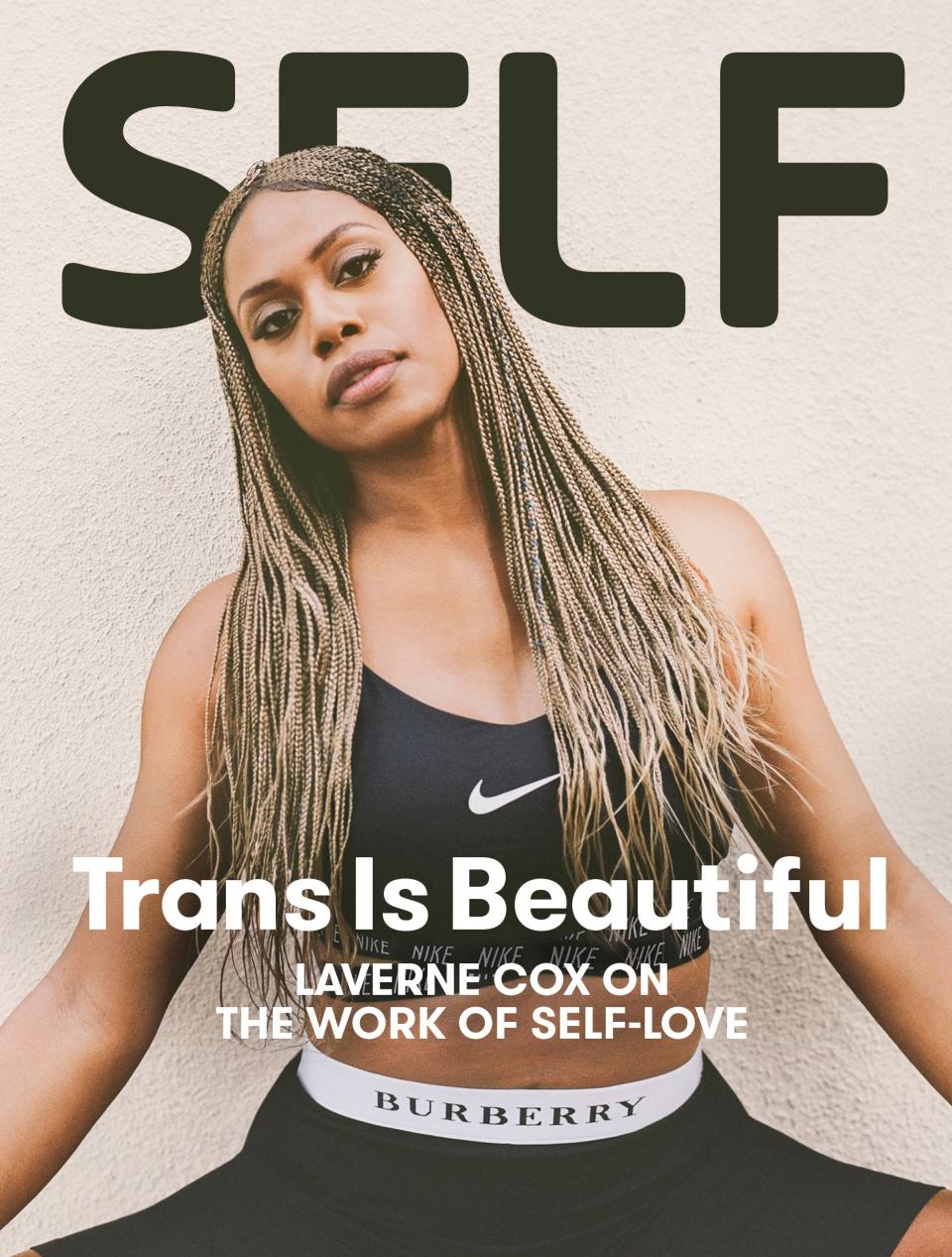

Trans Is Beautiful: Laverne Cox on the Work of Self-Love

As I sit in a secluded reception area of the AKA Smyth Tribeca Hotel in New York City, my phone vibrates with a text from an unknown number. It’s Laverne Cox, and she’s trying to find me. My first thought: I wonder if we’ll become friends after the interview is over. We’re both trans women of color, after all. And I’ve admired her for such a long time now, ever since I first saw her in her breakout role as trans inmate Sophia Burset in Netflix’s Orange Is the New Black.

My second thought is that I need to focus. I’m a professional journalist here to interview her for a profile. Yes, it’s all very exciting. But come on, Meredith. You’ve met celebrities before. Snap out of it.

I text her back and keep my eyes on my phone as I wait for her to reply.

Cox spots me before I spot her, probably because she’s wearing a black visor with a reflective plastic brim that goes down almost to her chin, obscuring her face nearly completely—a look that’s futuristic though slightly dystopian. “I must have walked right past you,” she says as she approaches me, visor down.

We go on a frenetic search for privacy through the hotel’s ground floor, breezing through a restaurant where Cox takes off her visor to talk to a hostess, who tells her the dining room is about to be cleaned, then to a lounge area next to a fireplace that still doesn’t feel quite right. Finally, Cox and I settle on a table overlooking the street outside, with translucent curtains covering the bottom half of the hotel’s front window and a screen shielding us from other tables behind. It’s only then that she seems to relax and allow herself to be seen, at least partly. She orders a pot of Earl Grey tea, which she sips languidly throughout our interview.

Even without her visor, the hood of her fitted black hoodie comes up over her head, and her chest is curved inward, her guardedness a contrast to her open smile and bearing on TV talk shows and red carpets. She reminds me of a turtle (well, a really glamorous turtle)—hiding within a shell, conserving her energy for when she needs to be out in the world.

Cox has every reason to be protective of herself, given that she’s one of the most recognizable transgender celebrities on the planet who simultaneously navigates the world as a black trans woman. These two realities may seem in stark contrast to each other—one defined by tremendous success and the other linked to deep oppression—yet they have in common a feeling of intense scrutiny, especially in public surrounded by strangers.

Ergo the visor, the frantic search for privacy, and I sense a certain emotional remove that could very well be interpreted as diva-like as we begin to talk: her gaze above instead of directly in my eyes, her chin tipped upward as she leans against the back of a brown leather bench, as far from me as possible. This feels like a pushback against my expectation that Cox be receptive and warm, that her public should see her as the perfect picture of grace, the kind of celebrity who makes time for her fans and always welcomes selfie and autograph requests with a smile.

Among trans women, there’s also the expectation that we should immediately connect through our shared history, an expectation I realize I totally had coming into this interview. It’s with a mixture of surprise, puzzlement, and grudging respect that I greet Cox’s demeanor, the way she seems prepared not to be nice if she doesn’t feel like it, even for a profile, even when her interviewer is another trans woman.

Cox grew up in Mobile, Alabama. Her mother, a teacher, stressed the importance of education, and, crucially, encouraged Cox to pursue her passion for dance and the arts from a young age, signing her up for dance classes starting in the third grade.

“When my teacher said you should take that child out of those dance classes, my mother said no,” Cox says. “It seems really basic but that's an incredible privilege because there are a lot of kids who were assigned male at birth who wanted to study dance and whose parents say no.”

The arts have been an emotional outlet for Cox since she was a child; she trained for years in classical ballet before fully focusing on acting after college. “Performing was this wonderful release for me as a kid,” she says. “Having music in my head and movement in my body was the thing that sort of transported me from Mobile, Alabama, where I was being bullied [...] where no one really understood me, to a space of possibility and dreams and my imagination.”

Dance opened up her world in ways that many black children who come from low-income and single-parent households like Cox’s don’t typically have access to. For high school, she won a scholarship to attend the Alabama School of Fine Arts, which attracts students from all over the United States. Being surrounded by classical pianists, opera singers, dancers, and actors engaged in the artistic process on such an advanced technical level drilled home for her the importance of hard work. “I worked really, really hard,” she says. “I understood how hard one must work to really be good at something.”

She attended Indiana University Bloomington on a dance scholarship, then transferred to Marymount Manhattan College her junior year, eventually earning a BFA in dance. She remained in New York after college, where she shifted her focus to acting and continued her hard work, now balancing her auditions and acting classes with waiting tables and other jobs to help pay the bills. She landed a few small acting roles here and there, and appeared on a reality television show called I Wanna Work for Diddy about a decade ago; then, in 2012, she was cast on Orange Is the New Black.

Her acting on OITNB catapulted Cox to stardom and paved the way for many firsts: the first openly trans person on the cover of both Time and Cosmopolitan; the first openly transgender actor nominated for a Primetime Emmy Award in the acting category (she subsequently earned a second nomination); the first openly transgender woman to win a Daytime Emmy Award as an executive producer, for her work on Laverne Cox Presents: The T Word. In the process, Cox also became the face of the trans movement for an entire country, during a time when interest in transgender issues has surged.

Throughout our conversation, as I listen to Cox expound on her acting process, as well as her love of classical music and ballet, I realize, sheepishly, that her outstanding performance as Sophia on OITNB has become so ingrained in my mind that I have conflated that character’s biography with Cox’s own.

While Cox and the role she is most known for have the common experience of being black trans women, their lives are entirely different. Unlike the character she plays, Cox was not married to a woman, has not had a child, has never been to prison. These are aspects of Sophia’s character that Cox, through her training and hard work, has had to learn to embody—just as any trained actor who wishes to be evaluated for her talent must do. Cox’s life trajectory challenges the idea that trans actors are not trained, or that it’s less of a challenge for them to play trans roles because of their experience.

“The proof is in the work,” Cox emphasizes. “We can do the job. I mean, the only issue is about the opportunity. Because I'm black and because I understand my history as a black American, I don't mind having to prove that over and over again. I'm OK with that.”

Cox has 3.3 million followers on Instagram. She frequently posts photo and video updates from her life—many featuring her dancing playfully in front of the mirror, making sexy, silly, joyful faces. In her Instagram captions, Cox often uses the hashtag #transisbeautiful—trans is beautiful. It’s at once an affirmation, a mantra, and a rallying cry, the endpoint of a long journey where Cox grappled with her place in the world as a black trans woman. “When I started transitioning 20 years ago, the goal of transitioning was not to be openly trans,” she says. “The goal of transitioning as presented to me by all the trans women that I admired was that you transition and you go and disappear and don't tell anyone your business.”

Cox is fully aware that many trans people struggle to find themselves beautiful, as she still does from time to time. For years, she says, she didn’t have the luxury of moving through the world without revealing she’s trans, a state that trans women refer to as stealth. “There were a lot of times over many years I went through the world not leading with being trans, but someone always knew,” Cox says. “I had to really get to a place in my life where I was able to be good with being trans or I was going to have to kill myself.”

Cox talks about self-love and self-acceptance as a process that involves work on multiple fronts. She says therapy is key to being in touch with her own self-worth, but also that acting itself has been a great tool for helping Cox understand herself.

“I think actors must know the very depth of who we are as human beings so that we can give the depth of our humanity to the characters that we play and find where those intersections meet,” she says. “There's constant work of self-discovery, self-acceptance, peeling back layers of an onion that an actor must do constantly.”

Cox also repeats affirmations to herself in the mirror, which she describes as “cheesy,” with a chuckle, but effective. “There's a bit of cynicism that I, too, have had about doing affirmations, but it's really a wonderful thing,” she says. “Sometimes you say it until you believe it. I can't say I haven't looked in the mirror and said, “‘Work, bitch.’”

Cox squares herself, as if to prepare for her affirmation ritual. “I think it's important to be able to be like, ‘Yes, your shoulders are broad, yes your hands are big and your voice is deep and you're really tall and people notice you, and that makes you noticeably trans, but that doesn't make you any less beautiful,’” she says. “You're not beautiful despite those things, you're beautiful because of those things, and [believing] that has to be an active conscious process.”

With this affirmation, Cox provides clues to the aspects of her physical appearance that society has taught her to dislike because they mark her as trans, and how tuning out the world allows her to tap into her own sense of beauty, apart from those social pressures.

“Loving myself is a practice,” she says. “It is something that I must cultivate and it is something that I must consciously do or it will go away.”

Beyond therapy and affirmations, Cox is intentional about tending to her physical and emotional well-being. She rattles off something of a self-care checklist: “Working out, eating well, getting enough sleep, saying no so I can balance work with pleasure and work with activism—and activism is part of my work, but having a more balanced life,” she says. “I still struggle with that.”

And then there’s her approach to love and dating, which has evolved significantly since she was younger. She says she used to believe that because she was trans, she had to accept men not treating her well, or only using her for sex. Her growing self-confidence has helped her see that she has every right to demand and expect respect, partnership, and love.

Before Cox met her current boyfriend, Kyle Draper, the CEO of a record label, she had some ground rules when it came to dating: She disclosed up front that she was trans, and she refused to meet someone new in private. In addition to being safety tactics, both of these steps also helped weed out anyone who didn’t feel comfortable being seen dating a trans woman in public.

She had other requirements for what she looked for in a partner as well: “Am I attracted to the person, does the person treat me well and make me feel good about myself, does it feel safe?” Cox says. “A friend of mine said, ‘Would you trust this person that you're dating around your child if you had one?’ I think about my inner child…re-parenting my inner child. Would that person be safe around my inner child?”

Cox jokes that when she met Draper, he checked all the boxes for what she was looking for—except, she thought at the time, he wasn’t tall enough. “If I'm being really real, it was about my ego,” she says. “When I dated men who were taller than me, it made me feel demure, it made me feel more feminine and all that stuff. None of that is about a real connection with someone. It's about how we might look together in a photo, about superficial shit.” Draper was really funny, though, and kind as well as charming; he also made her feel good—and she thought he was sexy, too. Suddenly, she didn’t care about the height thing anymore. A year and change later, they’re happily in love.

I tell her that the story of her romance with Draper feels connected, in a way, to the whole idea of trans is beautiful, and setting aside certain societal standards of what beauty should be or should look like. She agrees that her feelings about height, for instance, were because she wasn’t fully at peace with who she was or how she looked. “I wanted a man to validate my womanhood or validate that I'm attractive,” she says. Because for so long, so many people have told her that she’s not. Men have told her that she’s not beautiful or sexy, even while simultaneously wanting to have sex with her. And she came to the realization, through acting, through therapy, through her affirmations, and through her slow building of her self-esteem, that she didn’t need to listen to it anymore.

“I'm not buying it anymore,” she says. “I'm not buying into that, I'm not having it. I'm sexy and I'm going to own that because I think trans women…are sexy. A lot of us are sexy not despite our transness, but because of our transness. That's just the truth.”

One of the most difficult aspects of being trans that people often don’t account for is that while we want to be perceived as we are in the present, we often carry with us significant traumas from the past. Even though Cox today may not seem visibly trans, she began her transition process two decades ago, and it’s clear that she spent many years moving through the world as a visibly trans woman who is also black, with the attendant pain and danger that identity often entails. Even if strangers are less liable to perceive her as trans now, her status as a celebrity identified with the trans movement means that she’s visibly trans in a different way, so ever since she transitioned, Cox has never experienced significant respite from her trans identity being up for display and scrutiny.

Given the high rates of harassment and violence against trans women, especially black trans women like Cox, it’s understandable that she’s under a lot of stress, both internally and in her interactions with the public.

To start, she contends with a pervasive, nagging feeling of guilt—what she refers to as “survivor’s guilt”—over her success, while so many other trans women of color suffer. “I understand that I'm very lucky,” she says. “I understand that I've been chosen. It makes me sad…it’s very intense.”

She’s acutely aware, both personally and intellectually, about the risks of existing in the world as a trans woman of color. Between 2010 and 2014, the approximate murder rate for young Americans (ages 15 to 34) in general was 1 in 12,000; the murder rate for young black trans women during that time period was 1 in 2,600, nearly five times higher than the national average, according to an investigation by Mic (that, full disclosure, I worked on). In the years since, the rate is reportedly increasing, according to the Human Rights Campaign, a civil rights organization for LGBTQ+ Americans. According to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS), conducted by the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and National Center for Transgender Equality, 41 percent of trans people report having attempted suicide. One in two trans individuals experience sexual abuse or assault at some point in their life, with some estimates as high as 66 percent, according to the Office for Victims of Crime within the U.S. Department of Justice. And according to estimates by the National Center for Transgender Equality, one in five trans people have faced housing discrimination, one in 10 have been evicted from their homes, and of the roughly 1.6 million homeless youths in America, an estimated 20 to 40 percent are LGBTQ+-identifying.

Cox tries to blunt her feelings of survivor’s guilt by remembering that she should be proud of what she’s accomplished. She’s worked hard to live the life she’s always dreamed about, and she has a right to enjoy herself, even if others like her don’t have the same luxury. Meanwhile, she’s mindful about her consumption and spending: “I think there’s a difference between materialism and wanting to live comfortably,” she says. “That's what I have to be really careful with, right? That I'm not just like conspicuously consuming and being materialistic."

She reminds herself of what it was like to be a kid, bullied in gym class, daydreaming about one day being famous and showing them all. “I think about that little kid and I just think that how wonderful for her, how wonderful for her that she gets to live these dreams,” Cox says. And she says her brother reminds her that representation and visibility are important, and that she’s showing other little kids all over the world that a black trans woman can be successful, happy, fulfilled—and enjoy herself. There’s something beautiful in that. But there’s also a lot of pressure.

“I better damn well enjoy it because I don't know how long it's going to last,” she adds.

Cox is anxious about this feeling of scarcity, too—that her fame will be fleeting, that all good things are temporary, that the other shoe might drop at any moment, and that she should enjoy it while it’s here. The anxiety can manifest in scary physical symptoms, like the “full-on panic attacks” she says she experienced when she recently bought a condo in Los Angeles. “I think in part it was because of not being used to abundance, because I've had two eviction notices in my life, and I hadn't fully dealt with that trauma,” she says.

Ultimately, Cox is not just any actor. The privileges of a strong arts education have not fully shielded her from many of the traumas that pervade black trans women’s lives. Moreover, Cox also functions for many as a symbol of possibility for an embattled community, one that looks to her for support and affirmation. And Cox finds herself constantly confronting this tension between her present position as an elevated exception and her past, which becomes clear when our discussion of preparing for a movie she’s in turns into a tearful look into the perils of being a black trans celebrity.

The movie is Dear White People director Justin Simien’s Bad Hair, a horror satire about a black woman and her weave, which Cox hesitates to describe at length because the film has only been announced recently. But Cox does recount the process of preparing for her role of Virgie, which she’s been doing by working with her new acting coach Kimberly Harris to find what she calls a character’s “private moment,” which leads to a discovery of her “unfulfilled need.” It’s a process meant to help an actor discover more information about the character, she explains.

Here’s how Cox describes the relationship between a character’s need and an actor’s own experiences: “[A character] has to match up obviously with your own unfulfilled need and your own traumas and it has to always be very personal for you,” she says. Maybe this is why Cox begins to shift from the needs of the character she portrays to her own needs, and how they match up with her own past.

“I don't usually take pictures with fans…if I'm not feeling it,” she says. “I have guilt about it.” It’s another item on the long list of social challenges Cox has to worry about.

Cox recalls how excited she was when OITNB came out in 2013, and how she went through a six-week period when she said yes to every fan request to say hello and take pictures. But at the end of that time, she says, “I was exhausted from receiving all this energy, from saying yes to everybody who wanted their picture. I was like, if I don't set some boundaries, I'm not going to have anything left for myself.”

Cox is able to ignore certain complaints from her dedicated fans better than others. For instance, she waves off the commenters who criticize her for dating a white man.

“It’s rough out there when you're a black woman,” Cox says, citing OkCupid dating statistics that show men on the site rate black women as less attractive than other races. “And then you add being trans to that, girl, you can't be limited. I don't think you should limit yourself.”

Cox believes that it’s much better for her to approach dating with an open mind. “I'm going where it's warm and I'm going where there's a connection. That's not about race, you know?” she says. And she’s not particularly preoccupied by the criticism anyway. “I can't live my life for other people,” she says.

At the same time, though, Cox is deeply affected when she disappoints fans in face-to-face interactions, a tension that she constantly wrestles with, one that clearly upsets her as we talk and her tone grows plaintive. It’s as if she’s trying to solve a confounding emotional puzzle, one for which there is no solution. She begins to talk about how negative comments about her demeanor affect her. I mention that I’ve seen people call her aloof. Cox pauses as if to bristle, only to admit, “I kind of am.”

She described an incident where she walked into a Jennifer Lopez concert and fans were screaming that they loved her but Cox didn’t respond, until people online expressed anger at her. “I wanted to be kind of normal and just go to J.Lo's show,” she admits, adding that she didn’t even remember anything out of the ordinary until she saw the comments. “To be honest, moments like that make me not want to leave my house.”

“It's really hurtful, I could almost cry right now,” Cox continues. “But there are many, many people I've disappointed when they've met me in person because I was not able to receive their energy, I wasn't able to listen to them or take a picture or whatever they wanted. That's hard.”

Part of the issue is that, for Cox, it’s hard to overcome the natural reactions she’s developed from a lifetime lived in fight-or-flight mode, fearing for her personal safety.

Pre-fame, strangers approaching her on the street often meant danger—she’s been kicked, she says, and she’s been afraid of being murdered for being trans. Now people approach her on the street primarily for different reasons, but it doesn’t necessarily feel any different.

“This is the truth [about] people running up on me in the street,” she says. “It's not like [suddenly] I'm famous and all my traumas have gone away.”

It’s as if when fans approach Cox, her experiences of fan adulation converge with her history of street harassment, which means that she carries an even greater weight than many other celebrities in terms of dealing with the public.

Even more difficult, because Cox is a prime representative for the trans community, she often finds herself on the receiving end of many heart-wrenching stories from trans people who, recognizing her from TV, immediately confide in her.

“I've heard the most incredible stories—people saying I've saved their life […] because I was on TV,” she says. “They were going to commit suicide and then they transitioned. And these are beautiful things. But, it's also a lot to hear all the time.”

She describes a specific incident in which a trans woman approached her while Cox was shopping, and said that her mother watched the show and told her to watch it, after the two had not been in touch for many years. It was a beautiful, sweet story, one she’s glad she was available to hear, but it’s also a lot to take in psychologically when just going about her day.

Cox is crying now, and I suddenly notice that the space between us has narrowed, as we’ve found ourselves leaning toward each other while tears fill her eyes. It’s as if she finds it hard not to be emotionally vulnerable, and I wonder if that’s part of why she presents such a protective façade in public. Through her tears, a moment of clarity emerges.

“I just had my ‘aha’ moment,” she says. “It’s that it's too much. That's what it is. It's like someone living or dying because I say hello or because I'm on TV and I know that's what happening, but I can't live in that every day because it's too much.”

We talk about other things, about how Cox’s relationship with her fans relates to patterns of codependency she developed from a previous relationship—“there's a part of me that wants to take care of everybody,” she says; how she doesn’t have to be friends with celebrities she idolizes, like Beyoncé or Oprah, because she wants to give them space to be human beings; how all your problems don’t go away just because you’re famous. More than anything, though, I feel as if we’re both absorbing what we’ve learned from our interaction. Just as Cox realizes that everything that’s happening to her—whether positive or negative—is too overwhelming, I realize that I, too, have been guilty of projecting unfair expectations of warmth and intimacy onto her simply because we belong to the same community, when she deals with dozens of other trans people every day. Maybe the best way to be someone who admires Cox is to give her space, to allow her to be who she is, and not take it personally if she doesn’t always meet your expectations or match your enthusiasm.

Our interaction ends as abruptly as it began, with Cox bidding a hasty farewell and skittering to the hotel elevator as soon as I tell her I’ll take care of the check. I think about her initial text message, how I had imagined becoming her friend. It’s clear to me now that we don’t need to be friends for me to continue to admire her, just as she doesn’t have to be friends with people she also admires. I also realize that one of the greatest gifts we can all give celebrities is to think of them not just as the characters we’re invested in, the symbols of success or happiness we’ve come to admire, but also as human beings with their own needs, traumas, and imperfections. As I look at the empty space where she had been just a minute before, I also can’t help but think to myself about what Cox’s unfulfilled need could be, that if she were a character in a movie and someone were to play her, what would be the emotional force that drives that actor’s performance.

This is what occurs to me: Not everyone has been good to Cox, so she needs to be good to everyone, even when being good to everyone isn’t something she or anyone is capable of. Often, as Cox is finding out, it’s more important to be good to yourself.