What traits do pregnant women, roaches share? Answer might help solve disorders

This week’s health briefs include a look at what happened to pediatric mental health emergency department visits post-pandemic and why an international team of researchers believes similarities between pregnant women and live-bearing roaches could further understanding of autoimmune disorders.

Pregnant roaches and humans

In hopes of better understanding fibromyalgia and other immune disorders, researchers are studying the transformation live-bearing insects undergo, including how they suppress their immune systems to accommodate being pregnant.

They focused on beetle-mimic roaches for the international study, published in the journal iScience. The scientists say beetle-mimic roaches and pregnant women physiologically have quite a bit in common.

According to a release from the University of Cincinnati, which was part of the large international study, “biologists see similar changes in the insect’s trachea, its immune system and the outer layer of its exoskeleton called a cuticle, which transforms to make room for the babies.”

The cockroach moms incubate their babies, rather than laying eggs. They also secrete a milky substance to feed them.

Related

“Nature has devised a myriad of reproductive strategies across the animal kingdom,” Bertrand Fouks, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Muenster in Germany, and the study’s lead author, said in the release. “From birds and reptiles to fish, lots of animals lay eggs. In mammals, egg laying is limited to echidnas, sometimes known as spiny anteaters, and the platypus.”

Foulks said few insects develop a “complex structure” to nurture an embryo, similar to a placenta. Also like human mothers, beetle-mimic roaches have a “far bigger parental commitment.”

The scientists note similarities with other creatures that are live-bearing, including cows, lizards and this type of roach, in terms of urinary and genital organ changes during pregnancy, as well as enhanced heart development and a changed immune system — all to allow their babies to grow.

“Researchers are interested in the link between our immune system and pregnancy,” the release said. “Women are less susceptible to infectious diseases but are far more likely than men to have autoimmune disorders such as lupus.”

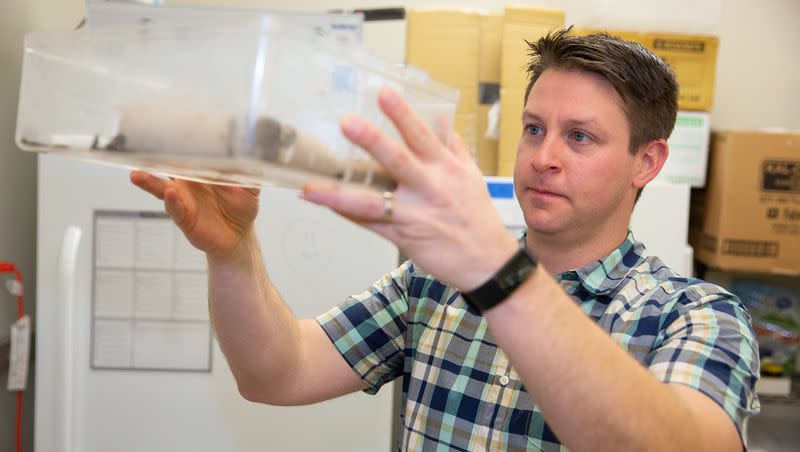

During pregnancy, some immune system genes are suppressed, which could explain why some women with autoimmune disorders get symptom relief while pregnant, said co-author and UC College of Arts and Sciences professor Joshua Benoit. Similar down-regulation of genes occurs in the live-bearing bugs, too, which means understanding them may shed light on autoimmune disorders.

Kids and mental health crisis

The number of children and adolescents who experienced mental health crises severe enough to send them to emergency departments skyrocketed during the pandemic. And now that things have calmed down on the pandemic front, experts expected the mental health crises to subside a bit, too.

But that hasn’t happened, according to researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian.

Instead, “pediatric mental health emergencies have increased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and continue to rise,” according to the study, published this week in the journal Pediatrics.

For the study, the researchers looked at rates of mental health visits by minors in the emergency department of five New York City medical centers, comparing the prepandemic numbers to those during five pandemic waves. All five had more visits to emergency rooms than before the pandemic, despite no evidence of a relationship between the visits “and COVID-19 prevalence or how strict mitigation methods were,” per the research.

“The pattern we saw is different than other tragedies because even after the acute COVID-19 emergency was over, we saw that an elevated rate of mental health emergencies persisted,” senior author Dr. Cori Green, vice chair of behavioral health in pediatrics and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine and a pediatrician at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital, said in a news release on the study.

“Our findings demonstrate the lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth mental health and their continued vulnerability despite our resumption of normal activity,” the study authors wrote. They added that “sociodemographic differences highlight opportunities to focus mental health resources on high-risk groups.”

The researchers also called for more studies to figure out the root causes and potential interventions to “mitigate the persistent and continually growing youth mental health crisis.”