Which TrainingPeaks Metrics Should You Actually Care About?

This article originally appeared on Triathlete

Maybe you've noticed (or maybe you deliberately ignore) the acronyms and corresponding numbers that appear within your TrainingPeaks app: TSS, CTL, ATL, and TSB. What are these metrics, and should you care? About all of them? None of them? Some more than others?

Most of them provide insight into your training ... probably. You should care about most of them ... at least some of the time. And ironically, the one you should care about the least (TSS) is the foundation for calculating the one you should care about the most (CTL).

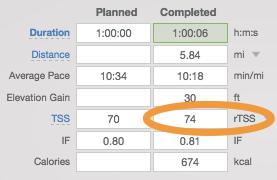

TSS. Training Stress Score. The number that TrainingPeaks spits out from some mysterious algorithm and which renders judgment on each and every workout. The number that is then used to quantify fitness (Chronic Training Load, or CTL), fatigue (Acute Training Load, or ATL), and form (Training Stress Balance, or TSB).

If we're going to rest our perception of training progress on the back of TSS, then that metric is worth a closer look. We'll talk about what drives the calculation, where there are shortcomings in the calculation, and why the metric is still valuable even if imperfect. We'll discuss how TSS spawns CTL, ATL, and TSB and also discuss when it's more appropriate to use other metrics entirely. Finally, we'll talk about which of these metrics you should actually care about – and when.

RELATED: 4 Pros Pull Back The Curtain on Their Data Screens

The TSS Calculation

Per TrainingPeaks, the TSS calculation for a bike ride with power data is:

TSS = (sec x NP x IF)/(FTP x 3600) x 100

Don't worry if that looks complicated – there's a lot going on there, and it's not necessary to understand the formula in detail. We can present it conceptually to make more sense out of the whole thing, and also generalize it for any workout with power, pace, or heart rate data:

TSS = (how much time you spent) x (how hard you worked) x (another way of calculating how hard you worked) x 100

The x100 on the end just transforms the resulting number from a decimal to a whole number, so we can ignore that part of the formula. And the other pieces of the formula are how long and how hard you trained, which are undeniably important factors when calculating training stress.

So, on its face, this seems like a good, general approach to calculating training stress.

Shortcomings of TSS

Ultimately, though, TSS really is just an approximation of training stress. There is a range of factors that drive how intensity, duration, and individual fitness influence training stress that aren't incorporated into the TSS formula. And sure, it would make for a pretty unwieldy calculation if we did incorporate all those factors, but it also makes for an imperfect calculation of training stress if we don't.

TSS Values Duration Over Intensity

If you look at the TSS formula above, you can see that "how hard you worked" shows up twice while "how long you trained" only shows up once. You'd think that makes intensity more important than duration in the calculation, but due to the relative scales of the two numbers, that's not the case. We can see this through a few examples:

A one-hour endurance bike ride (70% of threshold) has a TSS value of 49.

A two-hour endurance bike ride (70% of threshold) has a TSS value of 98.

A one-hour sub-threshold bike ride (95% of threshold, or a very strong Sprint-distance effort) has a TSS value of 90.

These examples show how increasing either duration or intensity effects the "base" value of a one-hour endurance ride. They also show that, according to the TSS formula, a two-hour reasonably comfortable endurance ride delivers more training stress than a one-hour very, very hard ride. I'm pretty sure your legs would disagree with that.

TSS Averages Workout Intensity

The TSS calculation looks at the average of how hard you worked in a training session, regardless of how you arrived at that average. So, for example, the formula doesn't differentiate between ten one-minute intervals and one ten-minute interval. And anyone who's executed both can tell you that they are very, very different.

(This, by the way, is why swim workouts often have disproportionally high TSS values. TrainingPeaks typically drops the time spent on the wall and the resulting minutes at zero intensity, which increases the calculated average intensity for the workout.)

TSS Doesn't Incorporate the Cumulative Effect of A Workout

The TSS calculation uses a linear function for duration, which is a math way of saying that the TSS for a three-hour bike ride will be exactly three times the TSS for a one-hour bike ride at the same intensity. Which means that each hour of that three-hour ride delivers the same training stress, according to the formula. But here's the thing: We all know that the third hour on the bike is way more tiring on your legs than the first. And don't even get me started about that sixth hour.

TSS Doesn't Incorporate the Cumulative Effect of the Entire Day’s Workouts

The TSS calculation for each workout doesn't account for any other training completed that day, including workouts that are done back-to-back. This is consistent with the linear function for duration discussed above, but is therefore also subject to the same shortcomings. For example, the TSS for a 30-minute run all by itself will be exactly the same as the TSS for an equally paced 30-minute run off the bike. Which means that, according to the formula, those two runs would deliver the same training stress. But it goes without saying that a 30-minute run off the bike hits your legs way harder than a 30-minute run done on its own.

TSS Doesn't Account for Your Current Fitness

The TSS calculation also doesn't account for how hard the workout is relative to your current fitness. In other words, the TSS for a three-hour bike ride is the same whether your current average long bike duration is one hour or four hours. Which is interesting, because in the former context the ride is deserving of a milkshake and a nap and in the latter it's a recovery weekend.

(Those who are well-versed in TrainingPeaks data might argue that CTL and ATL are where current fitness is incorporated. This isn't untrue, but it's also not necessarily sufficient.)

RELATED: Life Stress, Work Stress, Training Stress--Your Body Can’t Tell the Difference

Why TSS is Still a Valuable Metric

So, yeah, TSS is not the perfect measure of training stress. But while imperfect, the calculation is consistently imperfect. More specifically, the calculation is always imperfect in the same way.

That consistency means that, while we can debate whether any given workout's true TSS should be 55 or 62 or 49, we can feel confident that your workout with a TSS of 55 last week is comparable to your workout with a TSS of 55 from last month. In other words, while the absolute values may not be perfectly accurate, the relative values can still tell us a lot about your training.

The TSS Offspring: CTL, ATL, TSB, and Ramp Rate

We'll now take our consistently imperfect TSS values, roll them up, and package them in metrics that provide big-picture views about our training. Much like TSS, the absolute values of these metrics are less constructive than comparing relative values over time.

CTL: Chronic Training Load (Fitness)

CTL is a six-week rolling, exponentially weighted average of your daily TSS. Which is a math way of saying that it's a long-term average of how long and how hard you train every day, with your most recent training mattering more than what you did a while ago. Conceptually, this metric represents your current “Fitness.”

ATL: Acute Training Load (Fatigue)

ATL is a one-week rolling average of your daily TSS, and is just a half-way step between CTL and TSB. You can actually ignore this one!

TSB: Training Stress Balance (Form)

TSB is a balance of Fitness and Fatigue (mathematically, TSB = CTL-ATL). The number represents your body's overall ability to perform, both in training and on race day. This number is typically in the negative range throughout training, turning positive in close proximity to race days or during periods of prolonged rest and recovery.

Ramp Rate (Bonus Metric!)

Your Ramp Rate is simply the amount that your CTL has increased over a specified period of time; we typically focus on the seven-day Ramp Rate. If your CTL went from 65 to 71 over a week, you'll have a seven-day Ramp Rate of 6. Because Ramp Rate is a relative measure, this is one metric where the actual number holds value.

When TSS is Not Valuable

There is, however, one big, fat asterisk that can render TSS (and its offspring) completely irrelevant. The TSS calculation is based on your actual power/pace/heart rate relative to your threshold power/pace/heart rate; if your pace, power, and/or heart rate thresholds are not accurate in your TrainingPeaks settings, then neither is any TSS calculation based on that metric, or any metric based on TSS.

RELATED: How to Establish Triathlon Training Zones

If you don't know what thresholds are, or where they can be found within your TrainingPeaks settings, then assume yours are inaccurate. In that case, you can instead look at weekly hours and/or weekly mileage to provide insights into your training.

If you know all about thresholds but just haven't looked at yours in a while, this is a great opportunity to revisit those settings and update them if necessary. And if you do update your thresholds, you'll also want to recalculate any historical TSS values that were calculated off of incorrect threshold metrics. TrainingPeaks offers a handy TSS Backfiller tool to accomplish that task.

Which Metrics to Care About (and When)

Now that we understand TSS, its shortcomings and where it still holds value, its offspring, and its alternates, we can finally talk about which metrics to care about, and when.

Throughout Your Season: Evaluating Training Progress

Almost all of the metrics we've discussed can shed a light on how your training is progressing throughout your season. CTL does the best job of telling this story, but weekly total TSS or weekly total hours/miles work as well, and it's okay focus on your single favorite metric rather than all of them. Bonus points, though, are awarded if you follow the metric on a sport-specific level as well as in aggregate.

In most cases, effective training progress looks like increasing CTL numbers, weekly total TSS, and/or weekly total hours/miles; a 5-10% increase for any of these metrics is typically appropriate. Your Ramp Rate is another good indicator of training progress; seven-day values of 5-8 are appropriate for most athletes.

Throughout Your Season: Understanding and Predicting Fatigue

The same metrics that verify training progress can also warn you of impending fatigue. Increases in CTL, weekly total TSS, or weekly total hours/miles above what you historically can tolerate are a sign that you potentially need recovery.

(Speaking of recovery weeks, you should be able to see those clearly in your training. They show up as weeks with no increase, a very small increase, or even a slight decrease in CTL, weekly total TSS, weekly total hours/miles, or Ramp Rate values. If those don't appear regularly in your training logs, it's time to make adjustments.)

TSB and Ramp Rate are helpful in identifying fatigue brought on through short bursts (a few days' worth) of intense training. If you see TSB dip dramatically or Ramp Rate spike for more than a day or two, you will likely benefit from some immediate rest and recovery.

RELATED: Dear Coach: Is It Fatigue or Burnout?

Taper and Race Readiness

Tapering – resting up for race day – is more art than science. It's good practice to watch how your CTL, total weekly TSS, weekly total hours/miles, and Ramp Rate drop during taper (they are supposed to drop – don't panic!) as well as when your TSB goes positive and how high it gets before race day. Then evaluate how you felt on race day: perfectly ready to race? A little stale? Not quite rested enough? Adjust for your next race, re-evaluate, and eventually you will hone in your perfect taper formula.

One Last Note: When the Metrics Don’t Matter at All

Ultimately, the most important thing to remember is that the data is not the final judge and jury on your fitness and training or your ability to perform on race day. If you feel differently than the metrics indicate, defer to what your body is telling you: your body knows you way better than TrainingPeaks does.

RELATED: Your Watch Doesn't Know How Much Recovery You Need

Alison Freeman is a co-founder of NYX Endurance, a female-owned coaching group based in Boulder, Colorado, and San Diego, California. She is also a USAT Level II-certified and Ironman University-certified coach as well as a multiple iron-distance finisher.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.