How a Train Ticket From 1856 Solved My Family's Greatest Mystery

It was in 1990 that I began tracing my family tree, with my dad. We went through old photos from the attic, yellowed slips of newspaper with obituaries and birth notices, business cards and scrap albums, all in an effort to draw out our genealogy as far as we could. Almost everything was traceable, but we did encounter one missing piece, one family mystery that we simply couldn't solve.

On my father's side, we got back to to our Scottish roots in one step; my grandfather left Glasgow on the steamship Athena in 1906. On his mother's side we got back to Scotland and England in two or three steps, but one person was an enigma: my great-great grandfather, William Lozier Gaston. He was adopted. Were we French? Were we German? We had no luck in finding anything more about the Loziers, since we had nothing to go off of but his name.

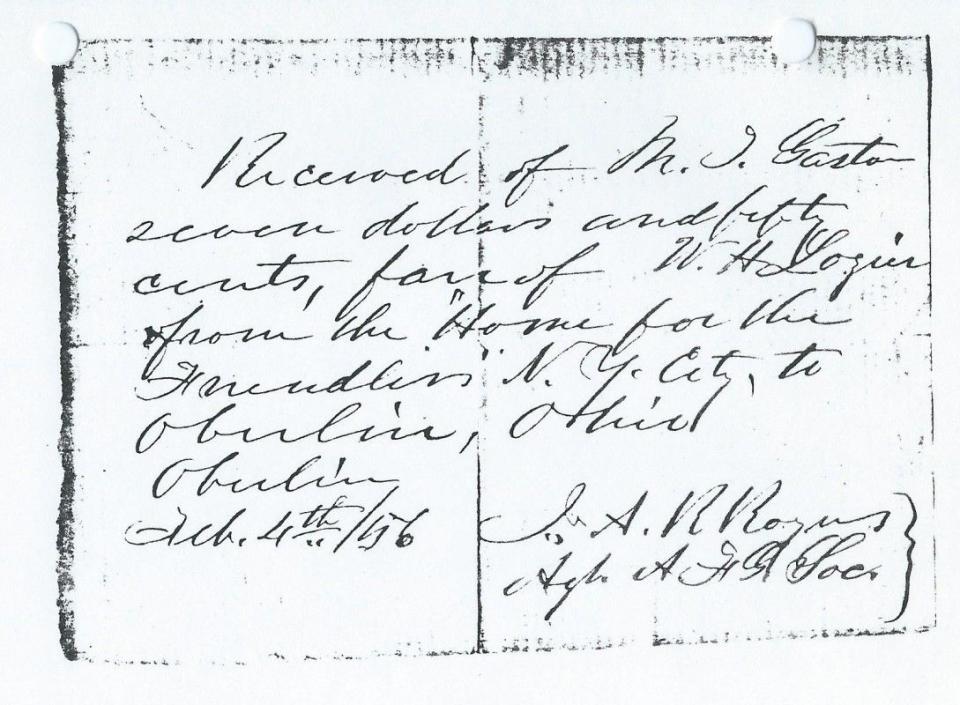

The only clue we had to Will's history was one slip of paper: the receipt for a train fare from New York's Home for the Friendless to Oberlin, Ohio, for $7.50, dated 1856. The scrap is a sales receipt for the exchange of the child from an orphanage to a stranger. Will was three-years-old at the time, so obviously someone took him to Ohio from New York.

And the family trail dies there. Although I occasionally wondered, I didn't think much more about Will — until I reae Christina Baker Kline's book, Orphan Train. The book rekindled in me a curiosity to know who this man was. I started internet-sleuthing to see what I could find about the orphanage, the era, and the origins of the so-called Orphan Train. It took about a month of late-night research before I found someone at the National Orphan Train Complex& who said she could help. I scanned the train receipt and sent it in to her. After some back and forth over email, I received a fat envelope of papers in the mail. "This is one of the most satisfying mysteries we've ever resolved," the volunteer told me. "You'll see."

When I opened the package, I opened up a whole new chapter in our family's history. Not only had Will been given up to the orphanage, but so had his two brothers and a sister. Their father had died in 1848, leaving Martha, his wife, to lose the family's farm in upstate New York. She eventually found her way to the poverty-stricken slums of New York City.

Following census and tax records, plus the archives of the Home for the Friendless, I saw that Martha had given up two of her boys to the orphanage, but kept the baby, Will, and her oldest girl. Martha worked as a seamstress, sharing a room in one of the infamously perilous tenements, in what is now the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan. As she fell deeper into poverty, Martha made the difficult decision to give up her last two children. They were all adopted.

Martha was undaunted; she worked and saved, and eventually wrote to ask for her children back. The orphanage did not respond. In those days, a child's moral and spiritual welfare were tantamount, and a single mother was seen as not fit to parent. Nevertheless, she found her way to her daughter, and at least one of her middle sons, if not both. Martha lived the rest of her life with her married daughter and her grandchildren. She died between 1900 and 1910, and she never saw nor heard of what had happened to Will, who grew up to be one of the top salesmen of pressed glass dishes in the Midwest. Will eventually moved to Riverside, California, where he helped raise my father — before he, too, was left fatherless by the hard times of the Great Depression.

I feel so sad for Martha, whose world spun out of control by the loss of her husband, her farm, and her children. She is key to a number of other amazing life stories in our line. Following her line back on various internet sites, I found that my 10th great-grandmother was a Native American woman known only as Lottie; her husband, my 10th great-grandfather, was known only as Johnson. When I took a DNA test and received the results, I saw a marker for Native American DNA. I had originally scoffed at that, thinking that the test must be wrong. But science doesn't lie. Through Martha, I found Lottie, and answered the riddle of my DNA.

And through Martha, I found our multiple connections to the Coffin family, founders of Nantucket Island and many whaling ship captains. I found our link back to the Mayflower, and my 13th great-grandmother, Mary Allerton, who was a child when she arrived with her parents as Pilgrims. I learned the lyrical, haunting names of my Puritan foremothers: Patience, Ruth, Waitstill, Freelove, Truthfull, Experience, and Silence. The men and women who came before me are with me still, in blood and bone — and possibly — as they say, genetic memory.

I haven't yet finished researching my family roots, but I have to hand it to Martha. She gave up everything to try and keep her children. I honor and treasure her, my unknown grandmother, for her grit and perseverance. I carry her DNA and her spirit with pride.

You Might Also Like