Torrisi Italian Specialties' New York State of Mind

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In this article:

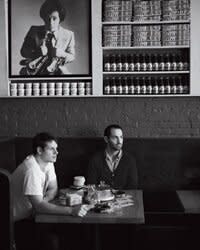

Rich Torrisi and Mario Carbone are side by side, spitballing ideas for new dishes. But the two young chefs are not shouting above the din of the kitchen in their tiny, two-year-old New York City restaurant, Torrisi Italian Specialties; rather, they are speaking sotto voce in the Brooke Russell Astor Reading Room in the Beaux-Arts main branch building of the New York Public Library. Torrisi and Carbone have been coming here frequently of late, poring over the library's extensive historic-menu collection.

Carbone studies the massive, circa-1917 menu of Luchöw's, the German-American restaurant that used to sit east of Manhattan's Union Square. "Broiled bear chop!" he stage-whispers.

Torrisi puzzles over the similar-vintage menu of Fleischmann's, a workingman's feeding spot on 11th Street that was owned by the same family that made Fleischmann's Yeast. "Farmer's chop suey," he says. "Only in America."

The chefs are looking not for recipes to replicate faithfully, but for inspiration: bits of New York culinary history that they can turn over in their minds and reprocess. For more than a year, they have been brainstorming, testing and tweaking dishes for a new menu they've taken to calling "the 2.0," a gastronomic tour of New York City that runs $125 a head and represents a great leap forward from what was already one of the most ecstatically received tasting menus of recent years. The 2.0, unveiled this fall, "shows us realizing our potential as chefs," says Torrisi. It is a remarkable achievement, a masterwork by two passionate, perfectionist cooks at the height of their creativity.

The backstory: Torrisi Italian Specialties was not quite half a year old when, in the spring of 2010, critics began gushing over its $50 prix fixe meal. By day, the restaurant functioned as an Italian-American deli, offering ideally realized versions of chicken-parm and eggplant-parm heroes—which served the dual purpose of allowing the chefs to acknowledge their paesano-boy roots and ensuring cash flow. By night, the space transformed into a 25-seat restaurant. The food remained unpretentious and Italian-American-inflected, yet it also showcased the haute training the chefs had received from such mentors as Andrew Carmellini (who employed both men at Café Boulud) and Mark Ladner of Del Posto.

A 1.0 meal at Torrisi began with a bowl of house-made mozzarella, still warm, served with garlic toasts. Then came dishes like a heritage pork chop slathered in bright-red vinegar peppers, or perhaps a skate wing in lemony Francese sauce: rigorous rewrites of red-sauce-joint classics, prepared using every tool and technique in a modern chef's arsenal to bring out the flavor. Given the restaurant's location on Mulberry Street—a Little Italy thoroughfare that has gentrified into Soho East—the food was not only clever and wonderful but also an act of cultural repatriation.

© John Kernick

Now, as a result of success and the chefs' restless imaginations, things have changed. The sandwich shop and explicitly Italian-American items have been off-loaded to a new restaurant next door, called Parm. "It's exactly the place you expect to find on Mulberry Street," says Carbone. There, you can order fried calamari, garlic knots, a wider array of heroes and antipasti than were available before and one "nightly special" entrée. Meanwhile, Torrisi Italian Specialties, its name notwithstanding, has morphed into a full-time prix fixe restaurant where the food isn't particularly Italian. The pew-like wooden benches remain, as do the shelf displays of Stella D'oro cookies, Progresso bread crumbs and Polly-O ricotta containers. The 1.0 menu is still available, and it still begins with the house-made mozzarella. But the bare tables are now covered in cloth, paper napkins have given way to linen and diners are presented with Tiffany oyster forks and Delmonico's crockery that Carbone snapped up on eBay.

These enhancements have come in the service of the 2.0 menu, which starts with very small plates the chefs call "bites" and continues with around a dozen tasting courses that veer all over the five boroughs, temporally and ethnographically. Torrisi and Carbone have been building up to this feat of audacity since autumn of last year. At that point, the food on the 1.0 menu was already slipping away from Italian and reflecting the polyglot influences of the surrounding neighborhood and the city in general; a course of lamb tongue, for example, simultaneously spoke Yiddish (the lamb was corned and adorned with pickle slices) and Greek (the lamb was also shaved, gyro-style, and served with dollops of tzatziki amid the pickles).

So why not take this New York City mash-up idea all the way? In preparation for 2.0, Carbone delved into what he calls "how it used to be" books, such as William Grimes's Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York and Judith Choate and James Canora's Dining at Delmonico's: The Story of America's Oldest Restaurant. Torrisi, to up his kitchen game, staged for short stints with two of the most inventive chefs in the world: René Redzepi of Noma in Copenhagen and Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck in Berkshire, England. And there were many visits by both men to the Astor Reading Room, though the dishes these visits yielded are like nothing that the room's namesake, society grande dame Brooke Astor, would have experienced at her clubby Upper East Side haunts.

Among the opening bites is a cigar-shaped gnocco fritto—an Italian fried-dough pocket—wrapped in smoked black cod and then dipped in the cod's bright-orange roe (to simulate a cigar's glow) and poppy seeds (to simulate ashes). "The flavor profile is very much like a New York bagel, the chew of the dough with smoked fish: Italy meets Jewish deli," Carbone says. And the gnocco is plated on a vintage Stork Club ashtray—"so when you're done," he says, "you're left with a dirty ashtray on the table."

© John Kernick

Another bite is an oyster pierced by a Tiffany fork, but it's a chicken oyster: that nugget of dark meat that comes off either side of the bird's lower backbone. Torrisi says, "We poach it in beurre blanc and dip it in a Chinese oyster sauce we make, then roll it in crushed cashews—"

Carbone cuts in: "—so it's like street-cart cashews, but it's also like chicken with cashews in a Chinese restaurant. And there's a Delmonico's reference, too, because Tiffany made flatware for Delmonico's. That's two New York institutions."

Torrisi and Carbone, 32 and 31 years old, respectively, are like a songwriting team at their collaborative peak: in full flower, not yet sick of each other. They met while students at The Culinary Institute of America, lived as roommates for a spell and still reside in the same Greenwich Village apartment building. Spend a little time with them and you see how their dynamic works. Torrisi, muscular and intense, comes off like a poet-prizefighter, wrapped up in the intricacies of technique. Carbone, serene and bearded like Caravaggio's Saint Francis, is more expansive, adept at contextualizing his partner's torrents of thought.

© John Kernick

Here's the two of them discussing the 2.0 menu's showpiece meat course, lamb chop Judea.

Carbone: "We wanted to do Roman food through a New York lens, and the New York lens is Lower East Side Jewish."

Torrisi: "In Rome, they do lamb chops scottadito, grilled with a marinade, right? So I thought of a glaze with 'house Manischewitz,' because I like the flavor of Concord grapes—"

Carbone: "—which are grown in New York state. And Manischewitz is based right over the river in New Jersey."

Torrisi: "But it's my own Concord-grape reduction for the glaze, and then we spice a Pat LaFrieda shoulder chop with celery seed and coriander, coat it with crushed matzo from Streit's and grill it hard and fast."

Carbone: "And combine it with one of the most popular dishes from the old Jewish Ghetto in Rome, artichokes fried in extra-virgin olive oil with mint."

Torrisi: "But we're frying Jerusalem artichokes instead of regular artichokes—"

Carbone: "A kind of Jewish pun."

Torrisi: "—in schmaltz instead of in olive oil. And we're adding in shards of dried chicken skin, with fried mint leaves."

Carbone: "Mint…Rome…mint jelly with lamb."

This free-associative playfulness obviates any concern that Torrisi and Carbone, in their fascination with old-time New York City foodways (and the Gilded Age dining palace Delmonico's in particular), might get caught up in turning out leaden, historically faithful museum food. They have an homage to Oysters Rockefeller, but it's a bite called Oysters Rocafella, and its inspiration is not the Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller but that latter-day New York entrepreneur Jay-Z, whose hip-hop label is called Roc-A-Fella Records. A freshly shucked oyster (a real one, not from a chicken) is presented on a bed of crushed ice interspersed with pieces of a smashed "Ace of Spades" Champagne bottle—"Ace of Spades" being the colloquial name for Armand de Brignac, Jay-Z's favorite brand of Champagne. The shellfish is topped with Champagne foam and served with frozen Champagne grapes.

There's a danger that all this flavor-layering and food-punning could get overwrought—more theme-park precious than fun or delicious. Torrisi says he, Carbone and their chef de cuisine, Eli Kulp, are secure enough in their friendship to call each other out on their excesses and half-cocked ideas. "Eli was busting us about the Oysters Rocafella, saying 'What, will there be Champagne bottles that flip open and play hip-hop at the table?' But you know what? You have to push the boundary too far to know what it is."

Torrisi and Carbone have already proved themselves to be shrewd boundary-pushers. The 2.0 menu represents another push, even further out there, but Torrisi is intent on his namesake restaurant becoming more than just the cool place to eat in 2012; he's aiming for a place in the Gotham pantheon. "I want it to be a classic New York restaurant," he says. "Not classic in the old-time sense, but embedded in the culture, like Babbo, Keens or Sparks."

Torrisi Italian Specialties: 2.0 Menu Dishes

Oysters Rocafella

Inspiration: Jay-Z

An homage to the Roc-A-Fella Records co-founder and Armand de Brignac Champagne fan, these oysters come topped with Champagne foam.

Knishes and Caviar

Inspiration: 1920s Caviar Service

Rich Torrisi and Mario Carbone treat their exquisite version of a potato knish as a kind of blini, topping it with fish roe, sour cream and dill.

Chicken "Oysters"

Inspiration: Chinese Takeout

At Torrisi, this elegant cashew chicken is made with a part of the bird called the oyster; each piece is served on a 100-year-old Tiffany oyster fork.

Grilled Lamb Chops

Inspiration: NYC's Lower East Side

A mash-up of influences from Jewish neighborhoods in New York City and Rome, these chops are glazed with Manischewitz and coated with matzo.

New York City writer David Kamp is a contributing editor at Vanity Fair and the author of The United States of Arugula.