Tori Bowie, Once the World’s Fastest Woman, Died Due to Complications from Childbirth

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Outside

Bowie died from complications related to childbirth according to an autopsy report released June 12 by the office of the medical examiner in Orange County, Florida, where Bowie was residing. Bowie was eight months pregnant at the time of her death, and her child, a daughter, was reported as stillborn.

Just four years removed from competing in the world championships in 2017, Bowie's death sent shockwaves throughout the sport. Although she had only raced once since 2021, she had been a world-class sprinter and long jumper for almost a decade, won three medals at the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, and won the 100-meter dash at the world championships in London.

On the track, Bowie was a world-class talent who won two U.S. championships, six global medals, and was once among the fastest women in the world. Off the track, she regularly visited foster children's homes and gave them holiday gifts, pushed for the elevation of Black women athletes, and was interested in a career in fashion and often modeled avant garde outfits. But those who knew her said she also struggled with anxiety, paranoia, and other mental and emotional challenges throughout her career.

"The track has saved my life. I would probably be dead right now," said Bowie in an August 2016 video. Bowie expressed her gratitude for the sport that gave her meaning and direction in life. "I was going on the wrong path, heading for destruction," Bowie said. "I was in the streets, you know, and wrong friends and just things like that my entire life."

Track did end up saving Bowie. On April 23, Frentorish Bowie, who went by Tori, died at the age of 32. She was found at home in Winter Garden, Florida, when Orange County Sheriff's deputies were called to perform a wellness check because no one had heard from her for several days.

Friends and Family Remember Tori Bowie

"It didn’t matter how much money was on the line," said her longtime agent Kimberly N. Holland. "It didn’t matter how big the opportunity was. She really had those issues within herself that we couldn’t help with. But we were there to walk her through or help her do whatever she needed to do." It's unknown whether Bowie received treatment for these mental health challenges.

Sarah Strong, ultrarunner and licensed clinical social worker with Fireweed Counseling in Colorado, said many elite athletes do not seek treatment. "There’s still a really big stigma about accessing that support," she said. "Some people think it’s just part of it, 'this is just what it means to be an athlete, you have to have this kind of anxiety.' And so then they don’t think it’s something that needs to be treated."

Athletes can also think it’s a sign of weakness to seek help, Strong said. "Olympians are notorious for trying to fight our way out of our things and try not to show any vulnerability. And we downplay a lot of things," said two-time Olympic Lolo Jones, who recalled getting to know Bowie while filming a television show for the Olympic Channel.

"Off-camera she was telling me bits of what she was going thru," Jones wrote in an Instagram post on May 3. "She had just gone thru a ton of Olympic success but had a lot going on personally, and it was hard for her to run. She made it seem like she just needed a little break and time to figure some things out. She didn't share any details of what but just runner to runner things. Like trying to find a new place to train, trying to find motivation, trying to finance her athletic career, I listened to her and tried to encourage her as much as I could from going thru the same issues on an Olympic cycle."

Bowie's Early Life

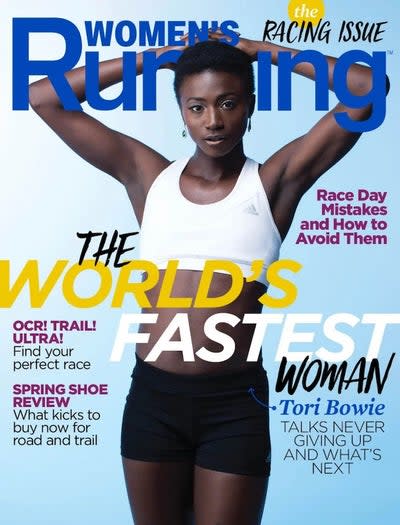

Bowie came from a challenging childhood in Sand Hill, Mississippi. Her mother gave her up to the foster care system when she was two, along with her three-year-old sister Tamara. Bowie never knew why, exactly, she told Women's Running in an article in 2018, when she graced the cover of the magazine.

"I never asked her about it," Bowie said of her mother at the time. "But she was going through her own issues."

Nine months later, the sisters were allowed to move in with their grandmother, which brought stability. "My grandmother's number one rule was that once you start something, you don't quit," Bowie said. "From a young age, she never let me give up on anything."

While she loved basketball and helped Pisgah High School reach the state championships, Bowie found her calling in track and field. As a senior, she won state titles in the 100- and 200-meter long jump, and anchored the winning 4×100-meter relay team.

That earned her a scholarship to the University of Southern Mississippi, where she excelled in a wide range of sprints, as well as the long jump and triple jump. By her junior year, she was named the Conference USA athlete of the year and emerged as a national star, winning the long jump at the NCAA indoor and outdoor championships.

Holland met Bowie in 2012 near the end of her college career, after a coach referred her. At the time, Bowie was set on being a long jumper, and Holland wasn't sure about representing her.

"She convinced me with her sweet, soft voice and just wanting to work with me," Holland recalls. They formed a bond from their very first phone call and from then on, Bowie called her "Ms. Kim."

"When we initially talked, we talked about mostly everything besides track," Holland said. "So there was a kindred spirit there from the very beginning. We talked for hours. I felt instantly a nurturing feeling towards her, like I wanted to help protect her. She just appeared so innocent."

In her first year as a pro in 2013, Bowie failed to make the finals of the 100-meter at the U.S. championships, but she took fourth in the long jump and competed well in overseas meets. It was about that time that Bowie sent Holland a video of her sprinting highlights and doing speed work for the long jump, and Holland was blown away.

"I just immediately jumped up," she said. "I was just like, 'Oh my gosh, this is the most horrible race that I’ve ever seen in 100 meters.' But she ran so fast, and I just got excited. If she can run a horrible race like this and run that fast, imagine what she could do if she actually trained for the sprint.' So I immediately called her and I was like, 'Tori, it looked like you were running from a Rottweiler, like you were running for your life.'"

Holland called Bowie, who was just 22 at the time, and asked if she'd thought about sprinting professionally.

"In her Southern accent she said, 'No, ma’am, I just want to break the world record in the long jump,'" Holland recalled. "I said, 'Tori, OK, I get that we can have fun with the long jump, but we can make some real moves in this 100 meters. I see all the potential. Like, you could really be the next one.'"

Holland was right. But it still took work to convince Bowie--as well as coaches and sponsors--that she had what it took. Holland secured a spot for Bowie in the 200 at the 2014 Prefontaine Classic, but only after a cancellation from another runner. Because of her slower seed time, Bowie drew lane one--a difficult lane to compete in, especially for a young, inexperienced sprinter--and wanted to back out.

"She was like, 'No, Ms. Kim, I can’t do that, I don’t even know how to set my starting block,'" Holland said. "I said, 'No, you are going to run this 200. What I had to go through to get you in this 200, you are going to run.'"

Bowie ended up winning the race with a world-leading time of 22.18 seconds, beating Nigerian Blessing Okagbare and Olympic champion Allyson Felix. Her career as a sprinter was secured.

"She ran like her life depended on it," Holland said. "After the race, all of these big athletes, they were all looking like, Who is that girl? Do you know that girl? No one knew who this girl was."

As she soared as a sprinter, she suffered as a long jumper. Despite being one of the top-ranked competitors heading into the 2014 indoor world championships, she finished last in the preliminary rounds.

On Top of The World

With the help of Holland and Adidas coach Lance Brauman, Bowie reluctantly put long jumping aside and worked hard at becoming the best sprinter she could be. By 2015, she emerged as one of the world's best as she not only won the 100 at the the U.S. championships but also earned the bronze medal in the world championships in Beijing, China.

The next year was even brighter, as she won 16 of the 19 individual sprint races. She finished third in the U.S. Olympic Trials in the 100 and earned a spot on the U.S. Olympic team, lowering her personal best time to 10.78. At the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro, she won both of her preliminary races and ran a stellar race in the finals to earn the silver medal behind Jamaica's Elaine Thompson.

Bowie also earned a bronze in the 200 in Rio and helped the U.S. win gold in the 4×100 relay, anchoring the team of Tianna Bartoletta, Allyson Felix, and English Gardner. By 2017, she was the best sprinter in the world. She won the 100 at the world championships in London in dramatic fashion-leaning forward through the finish line to clinch first place before falling to the ground. She also anchored the U.S. relay team to another gold medal.

View this post on Instagram

"Every single competition we had to prep her to run, it just didn’t come natural," Holland said. "She really had that kind of anxiety that she wouldn’t get on the track. So we had to pray with her before every single meet. We had to really motivate her, to convince her, you got this, you can do this. So that was another job in itself that we’ve never had to do with anyone. But whatever works, right?"

Holland had helped Bowie earn a lucrative contract with Adidas, and after Bowie's success at the 2016 Olympics, her career fortunes expanded with modeling gigs for Valentino and Stella McCartney, as well as an opportunity to be photographed by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue. But, Holland said, Bowie continued to struggle.

In 2018, Bowie allegedly got into a physical altercation with a training partner, and then a serious injury curtailed her season before the U.S. championships. In early 2019, she was removed from the U.S. Olympic Training Center because of a dispute over a $6,000 unpaid debt--a well-publicized incident that she said left her disappointed and disillusioned and in search of a new place to train.

After changing coaches and training groups, she went back to her first love of long jumping, and her physical talent and work ethic helped her shine once again. After a five-year hiatus from the discipline, she finished fourth at the 2019 world championships in Doha, missing the bronze medal by less than four inches.

"Tori was a very private, introverted person. Her circle was her management team or her family," Holland said. "And that wasn’t because she was mean. She was afraid to trust because she really felt that a lot of people didn’t mean well by her. That’s just part of the mental health issues that she had to deal with. And that’s why we had to do the things that we did to get her to run every single race. It was work every single race, every single competition."

Strong said anxiety is very prevalent among runners. Most recent research suggests that about 35 percent of elite athletes have either anxiety, depression, and/or eating disorders. And it's a chicken-and-egg question of whether anxious people are drawn to running or if running causes anxiety, she said.

"Many people seek out running because it helps with mental health, and people who are endurance runners are high performers. So people who maybe did have anxiety in other places in their life will start running. They love it and it makes them feel happy," she said. "And then once it becomes a competition and they’re doing it, suddenly it’s not about the running itself. It’s more about their identity, and they have this pressure to perform. I think elite athletes are more likely to have some of those things going on, comparing themselves with others that need to perform, that need to impress people."

Strong said that more elite athletes are opening up about their own mental health challenges--for example, Amelia Boone and Molly Seidel--and that decreases the stigma and brings more awareness for everyone. "Acknowledging that mental health is a thing and we can talk about it, and you can talk about it with your friends on your runs and we should normalize it," Strong said. "Not everybody must try to deal with it on their own."

"What I like to tell runners is, if your body can do the things that it’s doing when we’re treating our brains and bodies poorly, imagine what we could do if we treat that well," she said. "Sure, you’re showing that you can push yourself and do this, but imagine what you could do if you were taking care of yourself and your body was functioning optimally. You could be so much more successful."

A Track Season Derailed By COVID

Bowie didn't compete in 2020 as COVID-19 canceled most of the track season. In 2021, at age 30, she posted modest results in the 100 and 200 and didn't compete in the long jump at all. She opted not to participate in the COVID-delayed U.S. Olympic Trials later that year, either, which meant that just five years after being a top star in the previous Olympics, she wasn't even a contender to make the U.S. team bound for Tokyo.

Bowie was still training in early 2022, but she was no longer a world-class sprinter. In her only race, she placed fifth in a low-key 200 in Florida in 23.60--a time that didn't crack the top 400 in the world that year. By the fall, she was enrolled in Full Sail University in Winter Park, Florida.

Holland said the last time she spoke to Bowie was two weeks before she died, and that phone call felt like it was with "the old Tori," with the innocence and enthusiasm Holland had heard in their very first phone call. "We laughed and talked about old times, and I was just like, 'I just miss you so much, I really miss seeing you on the track,'" Holland said.

In that phone call, Holland said Bowie told her she was pregnant. Holland said she could tell the pregnancy was making Bowie happy, that she felt her baby would be a new beginning for her.

"You could feel the vibe, the rays over the phone," she said. "I welcomed it, whatever was going to make her happy. And so when I got the news two weeks later, I didn’t understand." Now Holland views that final phone call as a gift from God, one last chance to hear Bowie sound happy. "I hadn’t heard her sound that happy in a long time," she said.

Bowie's time at the top of the sport was brief but legendary. Her legacy as a world-class athlete won't be forgotten, but few ever really knew the internal demons she battled. Dozens of track athletes, coaches, and friends attended Bowie's funeral in Mississippi, including Holland.

Holland says she and Bowie had talked about reuniting after the baby was born-Holland says she offered to help take care of the baby. Now that won't happen, and the news that Bowie died due to complications from childbirth has sent ripples through the running world. It's also drawn more attention to maternal mortality rates, especially for Black women.

"So heartbreaking. We need to take better care of our women, athletes, mothers. So many systems let her down," wrote elite runner Molly Huddle on Instagram. “Not even Olympic champions can feel safe giving birth in this country. We gotta do better."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.