I Took Bangladeshi Photographer Activist Taslima Akhter to New York Fashion Week—Here’s What Happened

I Took Bangladeshi Photographer Activist Taslima Akhter to New York Fashion Week—Here’s What Happened

There’s so much going on at any given Fashion Week, it’s easy to ignore what’s right in front you. Push past the scrum of photographers snapping shots of street style stars. Block out the squabble between showgoers convinced they’ve been assigned to the same seat. Disregard, as best you can, the people in the front row filming Instagram Stories on their phones. It’s all white noise. You tune it all out in order to focus on the fashion.

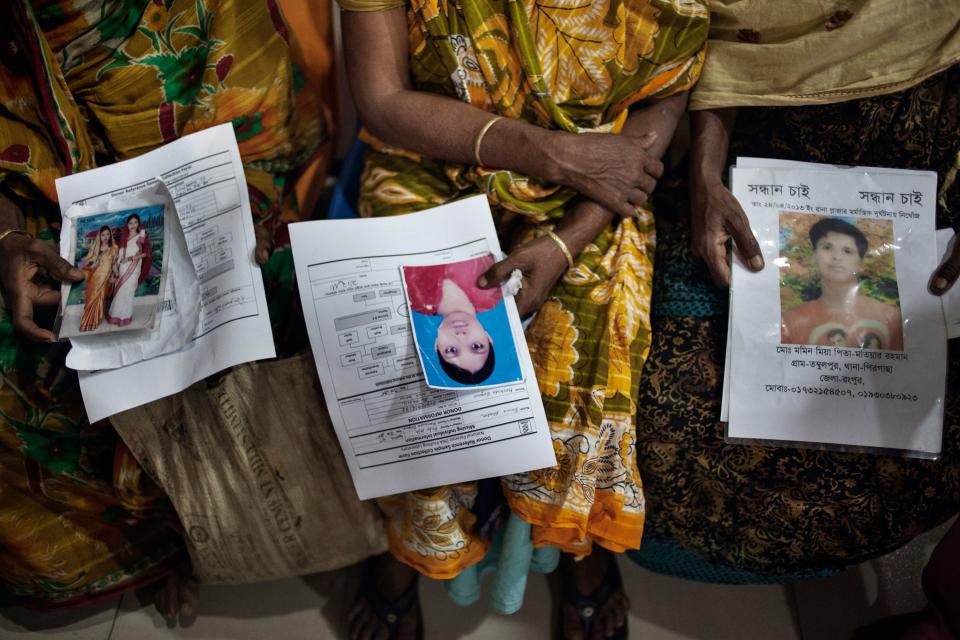

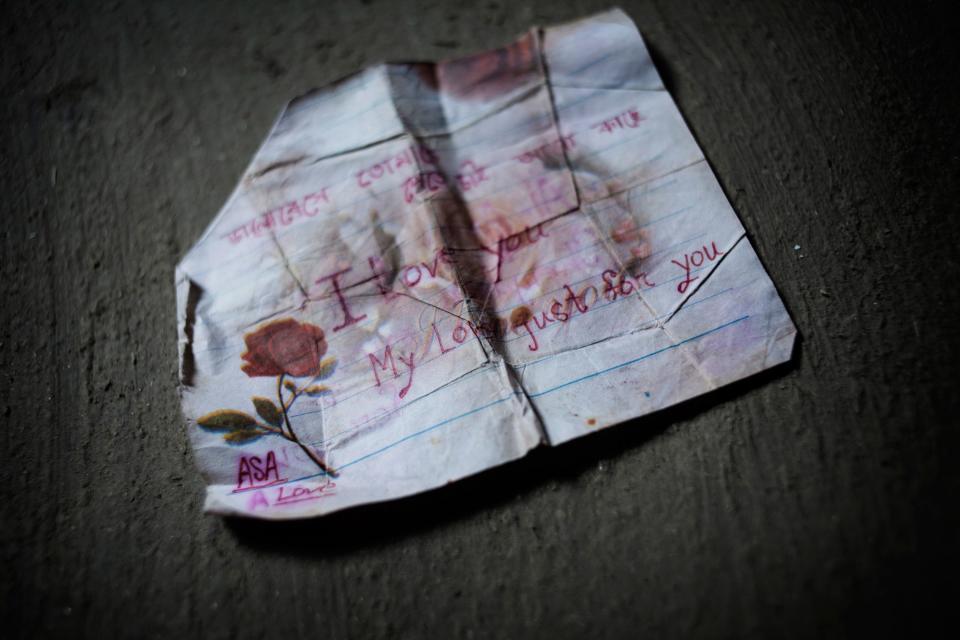

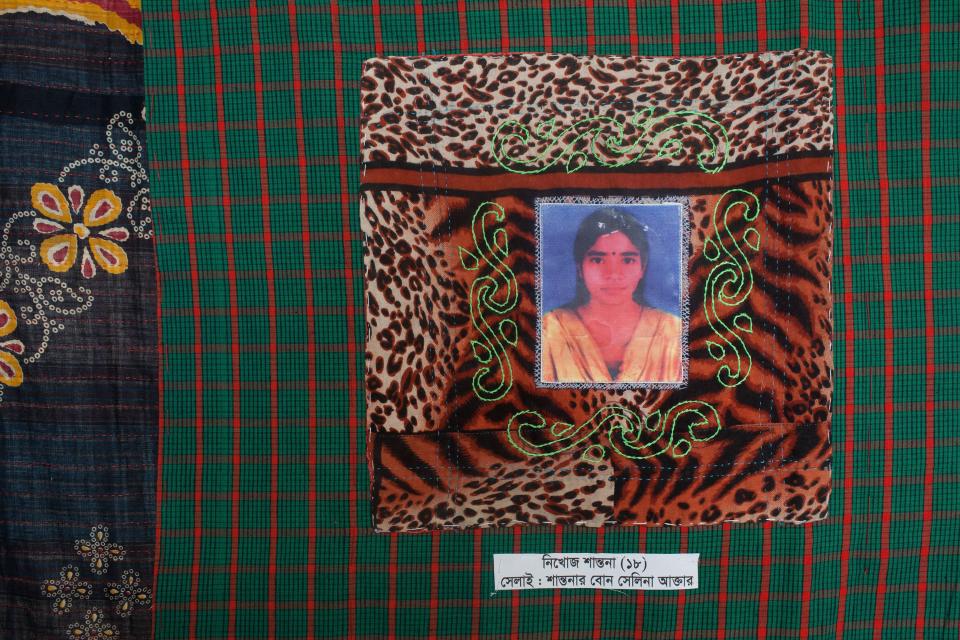

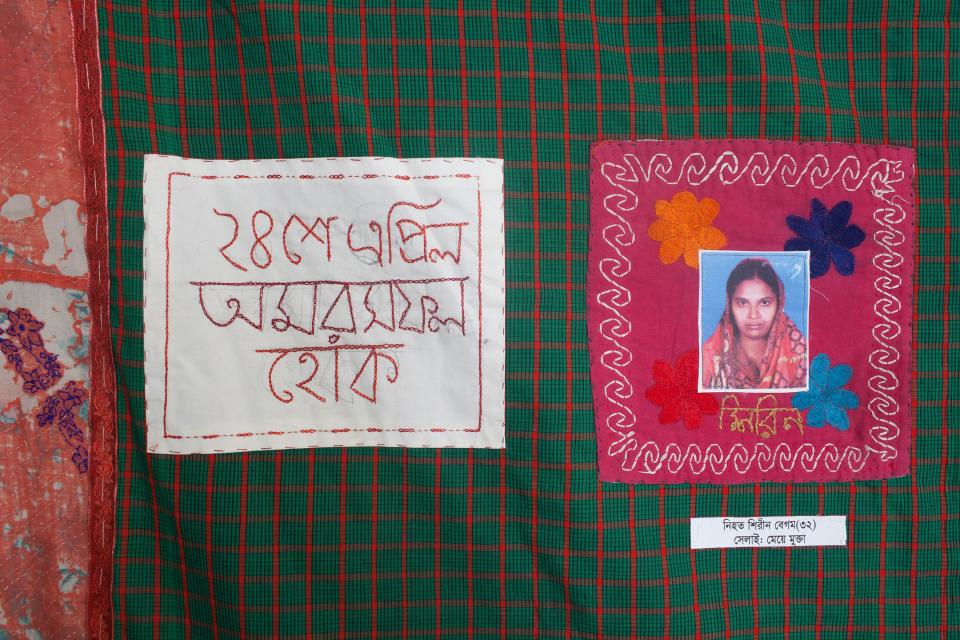

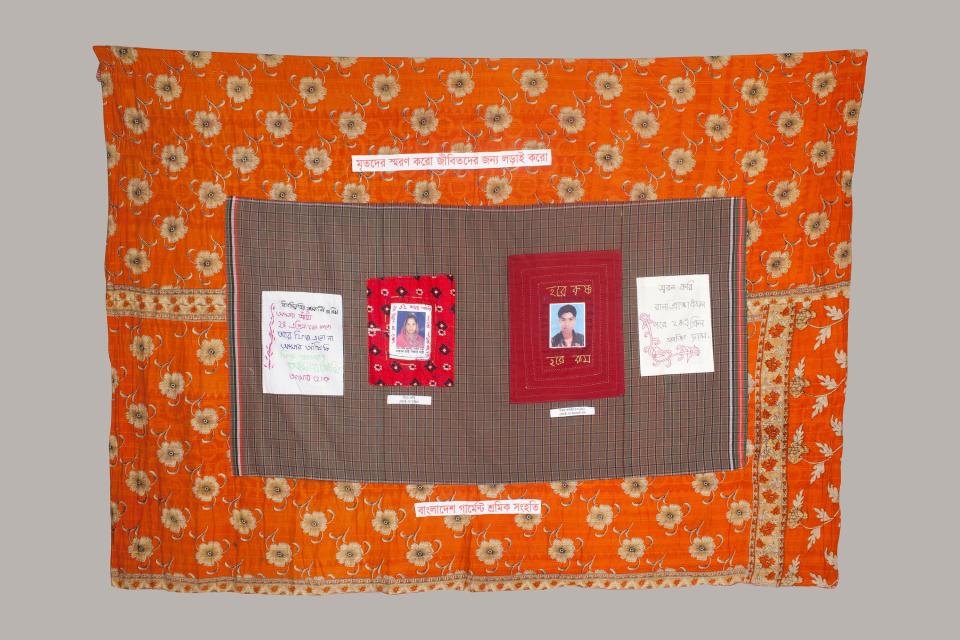

One way to tune back into the oddities of Fashion Week is to invite a newcomer to a show. In New York, photographer and activist Taslima Akhter accompanied me to Maryam Nassir Zadeh’s défilé in Tribeca. Her view of the fashion world has been very different from mine, and from most fashion showgoers’: Based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Akhter is immersed in the world of garment workers. She was in the city for Photoville, in Dumbo, where her exhibition “Stitching Together: Garment Workers in Solidarity” was on display last month. Presented by the Magnum Foundation, “Stitching Together” is composed of quilts that feature fabric-printed photographs of workers who died in the collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013. Looking at the quilts, I wondered whether there was a way to stitch together, as it were, the story about fashion that Akhter is telling, with the more visible one on the runway.

Seated beside me at the MNZ show, Akhter eagerly snapped photos of the models as they strode toward us—although, when the show was over, she demurred from giving me her opinion of the collection. As Akhter had previously pointed out to me, Bangladesh is a culturally conservative country, and most women still wear traditional garb such as saris or shalwar kameez. The midriff-baring tops and bicycle shorts in Zadeh’s collection would look outlandish there. (One might assume that most of the clothes Bangladeshi garment workers are asked to sew look pretty outlandish to them, too.)

What Akhter was thinking about, she said, was the disparity between the retail price of the MNZ clothes, which she could only guess at, and the wage of a Bangladeshi garment worker. Now, Maryam Nassir Zadeh doesn’t produce her collections in Bangladesh, but as we all know, ideas she worked out on her runway will likely show up on mood boards in the design studios of various fast fashion brands that will then send specs for their own reinterpretations on to factories in Dhaka and Chittagong. In theory, a garment worker in Bangladesh could be sewing a knockoff of one of MNZ’s ruffled skirts right now.

“I wish people knew that we’re fighting for a higher minimum wage right now,” Akhter told me. And when she said “right now,” she meant it literally: Nassir’s show was September 12; the day after, poobahs in Bangladesh came out with a proposal for a minimum-wage hike ahead of the country’s general election in December. Advocates for the garment workers were asking for a monthly minimum wage of about $190 a month; the proposal from the government came in at $95.

The vast majority of low-wage workers in Bangladesh labor in the garment sector, and the last time they got a raise, it was in the aftermath of the Rana Plaza disaster. The minimum wage, at present, is $63 a month. For context, the generally agreed living wage for a worker in Bangladesh is approximately $250 a month, based on the cost of lodging (a room in a slum runs $30 a month, at least) and the caloric requirements of the average Bangladeshi. No wonder that garment workers sign up for backbreaking overtime—it’s the only way they come close to meeting their basic needs.

Meanwhile, inasmuch as international focus has shifted away from Bangladesh in the five years since Rana Plaza, the Bangladeshi government hasn’t been shy about cracking down on protesters advocating for a significant wage hike, among other demands, like the right to take toilet breaks. “It’s difficult for us to make any real change without attention from the West,” Akhter explained. “Most of the profit, really almost all of the profit, in these clothes goes to the brands. So the brands need to come forward and say, ‘Okay, yes, we will pay what we need to pay.’ ”

Brands will only feel compelled to make that commitment if consumers pressure them to do so. And consumers will only consider applying that pressure if our conception of what it means to “focus on fashion” evolves to include the people in far-flung places sewing our T-shirts and sandblasting our jeans. With the Fashion Week circus now behind us, maybe take a moment to check your labels, and have a think.

The website for Taslima Akhter’s organization is AThousandCries.org.