I Took 30 Days Off From My Job, Family, and Cell Phone—Here’s What Happened

I hadn’t expected to need such a break. A few weeks, I thought. The only parameters were that it be warm, relatively safe, and far, far away from Donald Trump. But slowly, as the shape of it started to take form, I realized that what I actually wanted—and needed—was a dramatic break from my life. Particularly, my life with a cell phone.

My burnout had crept up on me quietly and stealthily. At the age of 31, I was thrown into a period of emotional tumult that would last for several years. In the space of six months, I lost my mother after a long battle (she hated that word) with cancer and I learned that my sister had made the decision to transition to becoming my brother. While it was a choice that I fully supported, a private part of me deeply mourned the loss of my sister. Our father had died suddenly when we were teenagers, and it had bonded us in the way that early trauma often does. Losing our mother was different, and we felt the permanent loss of childhood that comes with burying a second parent. But it also served to bring us closer. Now it was just the two of us.

As sisters we were completely different but fiercely loyal to each other. Though we are both about 6 feet tall, she had always been the lankier one. All angles, she had big feet, sharp cheekbones, and a devil-may-care look that people found irresistible. She was a musician, a model, a vagabond, and the utterly rebellious opposite to my careful, planning personality. In some ways, her transition was unsurprising because she was always fearlessly out front, while I hung back.

For a while, I didn’t talk about the transition. She had become he, but it wasn’t really my story. His bravery often brought me to tears, and I worried constantly. But how could I feel anything so selfish as loss? Still. His transition, coupled with the loss of our mother had, with some finality, put an end to my nuclear family as I’d known it. While most of my friends were getting married and starting new families, I was losing mine. The whole thing felt surreal and backward and yet oddly comical too.

In an attempt to process my grief and move forward, I threw myself into work. I made four films in as many years, worked most weekends, and floated in and out of relationships. From the outside, I was thriving. My career was in high gear. I was constantly on the move. My brother’s new life was taking shape, and our closeness had returned. I loved buying him Christmas presents at the Filson store and seeing him wear our dad’s old cowboy hat. Not surprisingly, he had become an incredibly handsome guy. People stared on the street. “Not fair! You don’t get to be good-looking both ways!” I would tease.

I was happy in work, happy in love and finally feeling that I was out from under the weight of grief. And that’s when the burnout hit. Fatigue always seems to strike when the worst is over. I tumbled down a deep, dark well of exhaustion. The physical symptoms were fairly common and easy to see. Acute headaches, neuropathy in my fingers, carpal tunnel syndrome in my wrists, and the hallmark sign of anxiety: insomnia from 4:00 to 6:00 a.m. But there were deeper ones too. My work suddenly lacked luster and flavor. I couldn’t seem to get excited about new projects on the horizon. I felt constantly irritable and overwhelmed. I audibly sighed. A lot. Looking back, it’s so clear to me. I could stifle my own grief, self-doubt, and anxiety in the frantic pace of emails and texts and social media. “Keeping up” was a perfect distraction. I was so busy taking in other people’s lives that I’d neglected to give my own a hard look.

Over lunch with my boss one day, I blurted it out. “I need to go away. For a while. At least 30 days. And I’m going to be gone. Really gone. No emails, no phone. No anything.” He looked at me quizzically and silently just nodded okay. Later, he laughed and admitted that it sounded like I was headed to rehab. In a way, I guess I was.

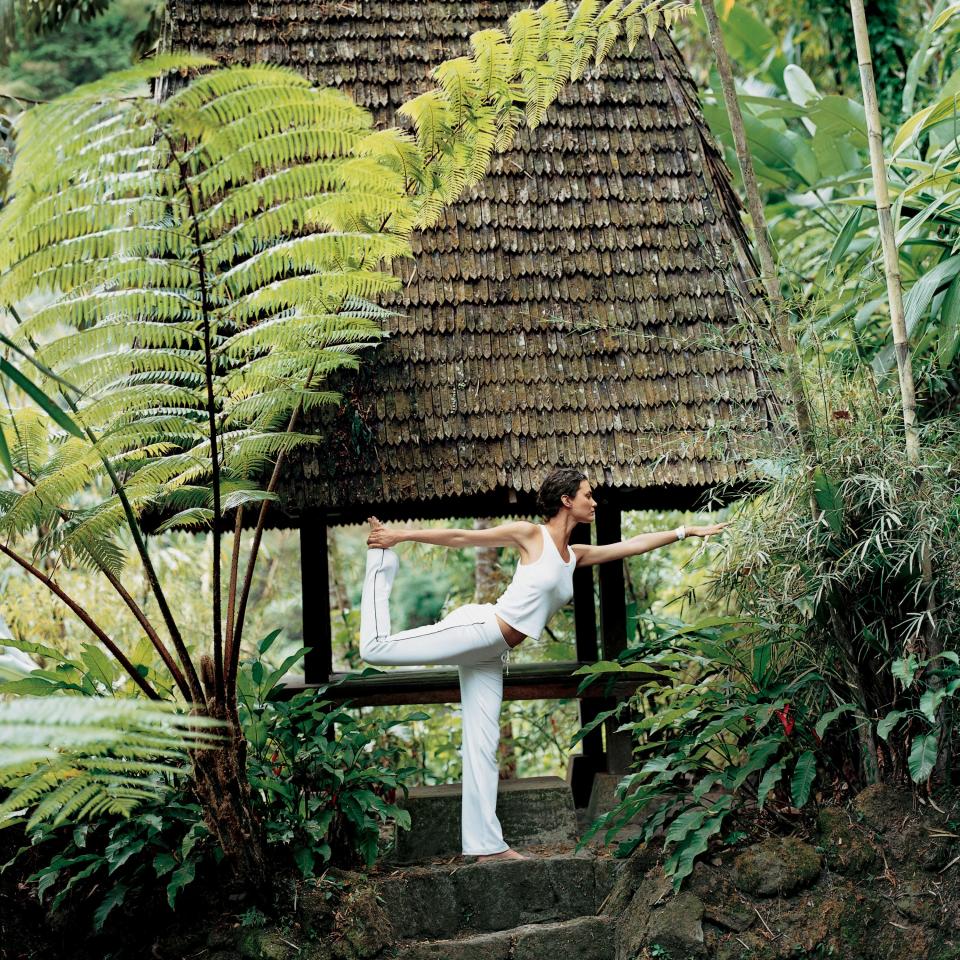

Which is how I found myself living in a thatched hut, perched over a lake, in the middle of a jungle in Sri Lanka. I’d chosen Sri Lanka because it was warm, relatively safe, and far away. I did some research (not a lot) and picked a spot that looked beautiful and remote. There was no electricity, WiFi, or cell signal. I had a simple cot for sleeping, a camera, and a headlamp, 17 books I had shipped ahead of time for entertainment, and about 394 varieties of insects for roommates. The place wasn’t fancy, and it wasn’t cheap. Despite the spartan surroundings, it was by far the most indulgent trip I’d ever taken. For a month, I’d have no schedule, no commitments, and no friends. I was a solo traveler with only time. I’d climbed Kilimanjaro, surfed Fiji, and backpacked the Teton Crest Trail, but this was terrifying.

The goal was simple. Spend 30 days off technology and observe what happened. I’ve never been much of a journal keeper, but it suddenly felt like a fun little science experiment.

The first few afternoons, it was all I could do to fight the spiraling pull of jetlag that felt like being tugged underwater. I was drunk on the scent of frangipani and jasmine. Sounds of the big, flat palm fronds slapping in the breeze wormed into my ears. The food was curried everything, with fresh lime juice to drink. Dappled light filtered through the trees. Colors felt brighter. The shades of green alone were dazzling and overwhelming.

Yet despite the virtual paradise surrounding me, there was a persistent anxiety. I’d frequently reach for something at my hip. Apprehensive that I was missing something, I obsessively checked through my grab bag of road meds and thought of the phantom pains that amputees continue to feel in the limb no longer there. Detached nerve endings calling the brain from a faraway place. Afternoon thunderstorms rolled in, the air stilled, and I would feel a low-pressure-system sense of dread. Several days of this went by before I realized it was my dormant cell phone I was missing.

Days were simple. Rise at six. Yoga for two hours. Breakfast, then reading. Lunch, more reading. Swimming in the late afternoon, maybe a walk. Two more hours of yoga followed by dinner. Asleep by eight. This all sounds like heaven or hell depending on the person. I was paying handsomely to live simply.

A day with technology consists of a million tiny little feedback loops. The iPhoto streams that banner across the screen, work emails about film budgets, likes from the latest (highly curated) Instagram post, and various group texts that punctuate any given day. I was a different person depending on the audience. Even depending on the platform. What happens when all that stimuli go away? Now there was just one feedback loop: whatever was immediately unfolding in that moment—right then.

My attention span became infinitely longer now that I wasn’t being interrupted every four minutes by my cell phone. Time started to collapse and stretch out in the funniest way. Cursing myself for forgetting a watch, I had no sense of “real time.” I could ask people if I got desperate (provided I could find anyone to ask), but mostly I just had to guess. Afternoons were long. Meals, quick. Waking up alone in the middle of the night felt like staring into the abyss. It could be midnight, or maybe 3:00 a.m. At 4:30, the monks in the monastery across the lake would start chanting and I’d hear the echoes. Mostly, I’d lie awake and think about having to pee. And what peeing would involve, which is cumbersome and a little scary in the jungle. I imagined a New Yorker cartoon about this internal argument, which goes a lot like the famous Five Stages of Grief. Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, and, finally, Acceptance. I’d snap on the headlamp, scurry out from under the mosquito netting and—praying the lizards, turtles, frogs, centipedes, and god knows what else that lurk in the dark water below leave me alone—squat over the hut’s edge into the lake.

I expected to have these rich, tapestried dreams. Instead, I dreamt each night about people I used to know. Friends from second grade with names long since forgotten, dredged up on some internal hard drive with names and faces completely intact. I remembered the forts we used to make in the backfields of our house, where we’d play for hours, the thrum of cicadas all around. My skin became the same temperature as the air. I returned to a childlike state. It made sense, in a way. The last time I was this disconnected from technology was childhood.

Time slowed and elasticized as my body became more nimble with telling it. The space behind my eyeballs started to relax and soften. My feet flattened out. My hair and nails grew like weeds. I was no longer grinding my teeth at night. No more headaches. Before long I was keeping farmer hours without any prompting. Down with the sun, up with the sun.

Harder to admit, I was still missing social media. There was no alcohol, caffeine, sugar, meat, and the only thing I still craved was Instagram. I’d think of how fabulous a picture of my experience would look. How it would “play.” Bumping up against my constant need to present my experience rather than just experience it. On the other hand, I’m a filmmaker. Imagery is part of how we tell stories. It creates a narrative that we can axis around. Most of my memories from childhood actually are images. Our brains trick us into thinking we remember organically, but mostly we’ve just seen the picture enough times.

I was often alone but oddly never lonely. I was bored sometimes. So I tried to make room for the white space to let things surface, the “in-between” moments when I would reflexively pick up my cell phone. That’s when the thoughts came. Like taking a long shower. I could have done this in a lot of places, I thought. Did I really need to go halfway around the world? I decided that I did. It took extreme guerrilla tactics to find solitude. Being unavailable is the last luxury these days.

At the end of my trip, I went to the southern coast for a few days of surfing. Getting around in a Third World country without a cell phone felt hairbrained and unnecessarily complicated at times. It was hot. I missed a lot of trains. Then I reminded myself it’s how every generation before ours managed to get around and decided to embrace the adventure.

I arrived in the little village of Weligama and waded into the water in the late afternoon. The ocean was warm and very salty. It was hard to imagine the tsunami that ripped through a few years earlier, leaving a path of loss and devastation in its wake.

My mother came to this town after the tsunami to do relief work. The place left a profound impact on her, and she returned again, a few years later, to continue the work. Through some miracle by the hotel staff, we tracked down my mother’s translator and friend from that time, Noelene. She took a six-hour bus ride from her village the next morning and cried the moment she saw me. “You look exactly like her,” she said. We spent the day together while Noelene showed me the things my mother loved: super-spicy street food, cold beer with lime, dancing with the locals. She had swum in this very water. I floated on my back, buoyant in the salinity, and tried to feel her.

I looked out at Taprobane Island, 100 yards offshore. A tiny island, accessible only by wading through the surf, with wide verandas and clambering palm trees and a gorgeous, crumbling colonial house. When I learned that Paul Bowles lived there (with no electricity) in the ’50s while writing the final chapters of The Spider’s House, I felt a sudden kinship to his need for solitude. Out in the Indian Ocean, among the birds and flowers, there’s virtually nothing between the house and the South Pole.

I thought I had traveled this far to be away, but I was actually trying to come home. Part of the ache with losing my parents was losing the only people who knew my story. In turning off for a month, I felt closer to them than ever, like the person I was when everyone was still alive together and we were a family.

The postscript to this story, of course, is the inevitable return to real life. On my last night, I sat on the hotel bed and stared at my dark phone. It had been in the bottom of my duffel bag for the last month. I took a long bath and wrote a letter to myself in New York. “Remember what this feels like,” I said. Knowing it would take more than two weeks for the letter to reach me at home, I wanted to ensure some shred of accountability once I was back in the real world. A follow-up visit from my tech-free mind. And with that last exercise finished, I turned my phone back on. Nothing crazy happened. I had just about the amount of stuff needing my attention that I’d expected. Turns out, no one misses you that much when you’re gone for a month.

Once back home, in my routine, I made a few small but meaningful changes in my day to day. I banished the cell phone from my bedroom, installed a landline, and bought an alarm clock. I fixed the battery in my wristwatch. I tried to remove as many reasons for looking at a screen as possible. I deleted social media from my phone (but kept the accounts), which has been huge in my happiness and productivity levels. Beyond that, much has stayed the same. The air mail self-addressed letter from Weligama has stayed unopened on my desk.