Do Tolkien lovers really need to know if female dwarves can grow beards?

Towards the back of the stately Blackwells bookshop in Oxford is a section dedicated to JRR Tolkien. Or, more precisely, Blackwells have a Great Wall of Tolkien. This formidable barricade contains all the usual titles: The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, The Silmarillion. But also more than enough to tickle the most recondite Hobbit-botherer - The Worlds of JRR Tolkien, The Flora of Middle Earth, Recipes from the World of Tolkien. Mushrooms ala Gandalf, anyone?

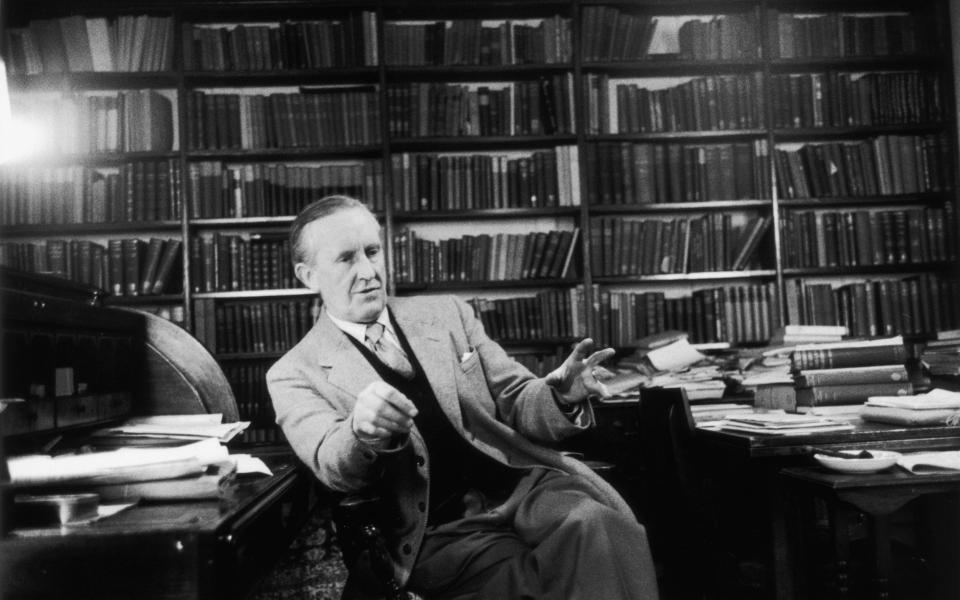

Fair enough: Oxford has a right to celebrate its native son. The city was where Tolkien spent much of his career as an Old English and Norse scholar; and where his stories of elves, orcs and wizards were first heard at meetings of the Inklings writing club in the backroom of the Eagle and Child pub. (Reception was not always enthusiastic - “Oh God, not enough elf,” fellow Inkling Hugh Dyson is supposed to have cried at an early draft of The Lord of the Rings.)

Blackwells, though, isn’t really to blame for this untamable riot of Tolkien miscellania. After all, it shifts like hot cakes to the tourist crowd, and at least no-one is lining up to pretend to push a trolley through a wall. Instead, this homeopathic approach to Tolkien’s inedible literary achievement - diluting its merits through yet another edition of The Wit and Wisdom of Samwise Gamgee - has one culprit: the Tolkien estate.

Therefore the news that they are to publish a collection of unseen essays, The Nature of Middle-earth, due in June 2021, left me with a leaden heart. I am an unabashed Tolkien lover. I’ve read The Lord of the Rings more times than I care to chalk up; my brother and I watch the film adaptations - extended editions, natch - every Christmas, tossing quotes back and forth with comradery glee. And I studied Old English and Norse at university, reading Beowulf to get closer to its “wild and primitive” atmosphere which did so much to inspire Tolkien’s own mythmaking.

But do we need to know whether dwarven women could grow beards? Or how many leagues are between Pelargir and Minas Tirith? These and other treats are in store in this new collection, we are promised. These questions are at odds with Tolkien's vision. Britain, Tolkien felt, needed a national mythos, like the Scandinavian Edda, to gee spirits after the bruising experience of two world wars and the loss of an empire. If The Lord of the Rings seems binary, then that is exactly the point. His Middle Earth has the sleek lines and comfortable moral clarity of a legend; the mess, muck and general murkiness of George RR Martin's Game of Thrones would have been anathema to him. Getting too bogged down in Middle Earth's specificities is a surefire way of muddying its magic.

Tolkien was a cautious, methodical writer and the fiction published during his lifetime is relatively scant. Aside from The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, only nine other titles appeared during a 30-year career. They are mostly playful experiments: allegorical poems, short stories and a medieval fable. He was a productive and highly respected academic; and fiction writing was an amusing sideline: a way for this prodigiously talented man to revel in his love of languages and story-telling.

The world of Middle Earth grew out of this spirit. Its earliest glimpses can be found in the mud and horror of the Western Front; Tolkien began sketching out its languages, races and mythology as a twenty-three year old Second Lieutenant on leave from the fighting. You do not have to look far to spot the broken landscape of the trenches in his books. The Dead Marshes, which guard the evil land of Mordor, are a foul swamp, draped in poisonous gas, where the faces of dead soldiers peer pale from murky waters.

It was this approach - writing as personal escape and salve - that explains why Tolkien left such a phenomenal stack of unpublished work on his death in 1973. In the decades since, his son, Christopher Tolkien, made it his life’s work to curate his father’s posthumous writing, doggedly pushing it towards the light of day. His extraordinary efforts had some undoubted success: The Silmarillion, a mammoth collection of Middle Earth mythos published four years after Tolkien’s death, is an invaluable companion to his world. It’s a rite of passage for readers who wolfed down The Return of the King’s appendices and have room for more.

But recently the trickle of releases of unpublished works has become a flood. And its returns have been ever-diminishing. Beren and Lúthien, released in 2017, was a repackaging of a story from The Silmarillion; its new standalone format cruelly spotlit its mishapenness. The Fall of Gondolin followed in 2018. It was, as with much of Tolkien’s work, gorgeously illustrated by Alan Lee. But that couldn’t plaster over its nature as an occasional piece, written in the teeth of war, over three decades before the first part of The Lord of the Rings was published. If it’s a relation of Tolkien’s most beloved tales, then you’d have to squint hard to spot it on the family tree.

Tolkien's estate are notoriously hard-nosed when it comes to managing his estate. They charged Amazon $250 million for the privilege of their forthcoming The Lord of the Rings adaption. That is exactly 1,000 times the sum that Tolkien received when he first sold TV and film rights to United Agents in 1969; and nearly as much money as New Line Cinema spent to produce all three of Peter Jackson's adaptions.

Which returns us to Harper Collins’s forthcoming essay collection. Harper’s publishing director Sam Smith says they are “a veritable treasure trove offering readers a chance to peer over Professor Tolkien’s shoulder at the very moment of discovery”.

It's a nice thought. But the magic of Tolkien’s world lies not in his discovery, but the reader’s. His friend, fellow writer C S Lewis, summed up this charm well in his review of The Fellowship of the Ring: “Not content to create his own story, [Tolkien] creates the whole world in which it is to move.” These incessant ‘unseen’ publications shrink that world. Learning about hairy-chinned dwarf women makes even Tolkien’s roomy universe feel small.