Is It Time For Us All to Start Hallucinating?

A doctor, a lawyer, an entrepreneur, and a clinical pharmacologist have come to the end of a road that leads up a wooded hill overlooking a valley on the Swiss-French border. Below, under blue skies and a few clouds of the type a child would draw, farm fields and a village centered on a white church with a black spire form a postcard image. Ahead, a muddy path and a slippery grass slope. Only the pharmacologist, a Swiss native named Matthias Liechti, has appropriate footwear. But they’ve come this far.

Scott Freeman, the doctor, flew from San Francisco to Basel, 12 miles away, to meet with Liechti. Tomorrow they’ll discuss clinical trials Liechti will be leading of a drug that the company of which Freeman is chief medical officer, MindMed, hopes to develop. The entrepreneur, J.R. Rahn, is MindMed’s co-founder and co-CEO (the lawyer, Stephen Hurst, is the other). Rahn is in town to meet with the administrator on the trial. Hurst needed to be in Europe at the same time on other business, so the MindMed principals, who all live in different cities, decided to convene in Basel for some old-fashioned face time.

Today they’ve taken an Uber—Rahn used to work at the company—up to the village of Burg im Leimental, where a small castle balances atop a rocky promontory. Once the road became too narrow for the Mercedes van they were in, they started hoofing it, about half a mile back.

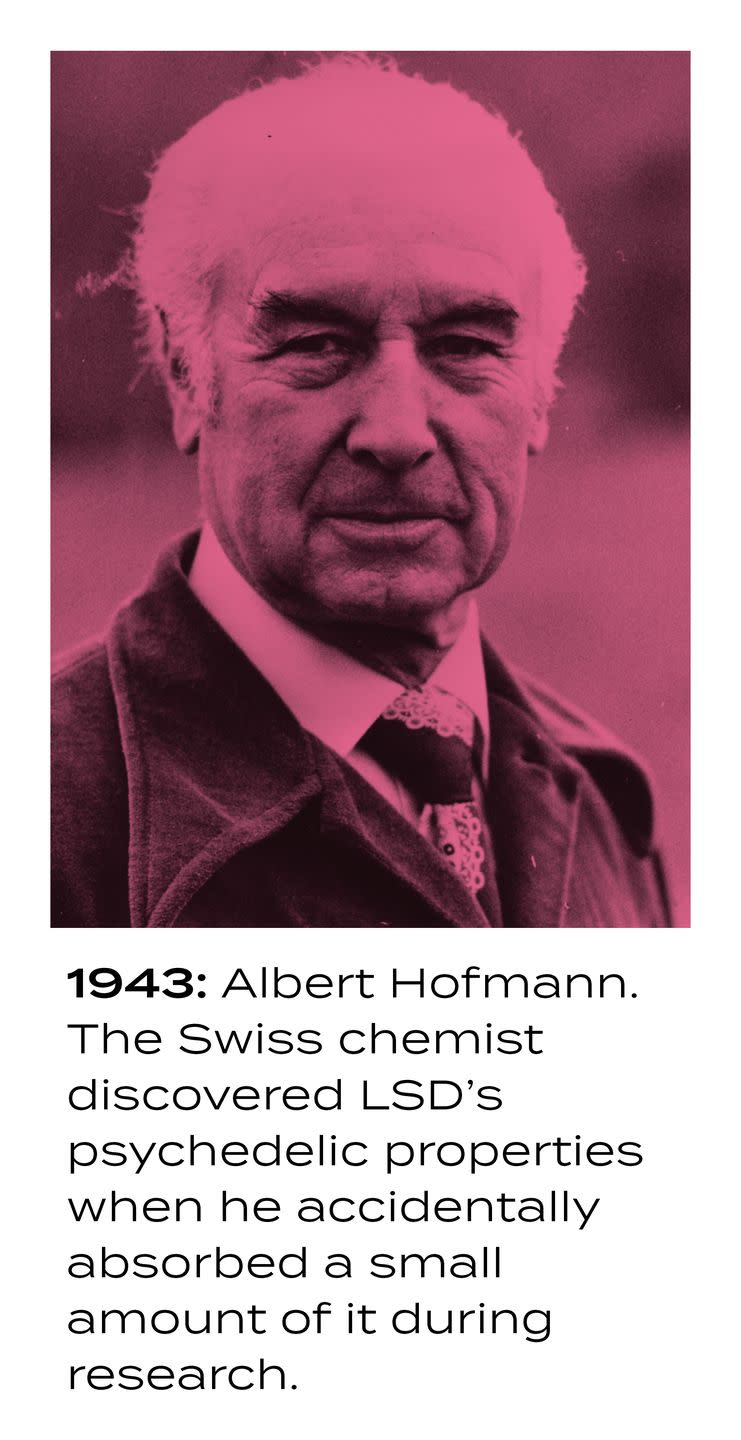

Forging ahead, the quartet passes a white modernist house, all corners and windows, that was the last home of Albert Hofmann, the chemist who first synthesized LSD, in 1938, while working at Sandoz, a Basel pharmaceutical company that today is a division of Novartis. The smokestacks of the Novartis factory can be seen in the distance. The men’s destination: Hofmann’s grave, 100 yards farther on.

The road the Uber followed from downtown Basel to Burg im Leimental is something of a Via Dolorosa for devotees of recreational LSD use. It is believed to be the route Hofmann took on his bicycle after he accidentally absorbed some of the compound in his lab in 1943, beginning the first acid trip (and one of the more ill-advised bike rides) in history. The men from MindMed are here on a pilgrimage too, though it’s purely professional in nature.

“Switzerland is the only place in the world where use of psychedelics in limited cases—as medicine—is allowed,” Liechti explains. That would be for cluster headaches, based on research being done at Liechti’s institution, the University Hospital of Basel. Though LSD has been illegal in the U.S. (and, effectively, everywhere else) since 1970, Liechti and a few others, in Basel and at the University of Zurich Psychiatric Hospital, have since the 1990s been quietly researching how psychedelics act on the brain, looking at LSD specifically since 2012.

In part because of Swiss national pride in Hofmann—he also isolated other compounds, including one that is still used to control postpartum hemorrhaging—the government has for several years allowed qualified researchers access to LSD to test its effects on volunteers.

Which is why New York–based MindMed is working in Basel. In March it became the first among several psychedelic pharmaceutical companies to go public, listing on Canada’s NEO exchange. You are not hallucinating: Psychedelic drugs, demonized by politicians, prosecutors, doctors, parents, and virtually everyone else for the last 50 years, are showing remarkable promise as a treatment for a host of significant health conditions, including depression, PTSD, addiction, inflammation, and more.

Venture capital is rushing in. Peter Thiel’s Breakthrough Ventures, and Able Partners, an investor in Gwyneth Paltrow’s wellness brand, Goop, are behind a London-based company that has patented a formulation of psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, for use with treatment-resistant depression. The evidence for psychedelics as medicine far exceeds the evidence for CBD, a compound in marijuana that companies are selling, based on basically nothing, to relieve ills ranging from Parkinson’s to Crohn’s diseases.

Liechti hopes to collaborate with MindMed soon to test whether sub-perceptual doses of LSD are an effective treatment for ADHD in adults—and there is actually some indication that it might work. “We’re using chemicals to enhance neuronal connectivity in the brain, opening different parts of the brain to talk to each other,” Freeman says.

Researching an illegal substance requires mounds of approvals. MindMed’s intention is to conduct all its clinical trials to the standards of the U.S. Food & Drug Administration. “We went to Switzerland,” Rahn explains, “because Dr. Liechti is the world leader in LSD research.” Not just anyone can conduct a trial using LSD. “So it’s logical to work with him—you can get started more efficiently.”

MindMed is also working on a compound derived from ibogaine, a psychedelic that comes from the bark of a tree that grows in central Africa, to treat opioid addiction. Ibogaine was extolled by the late banking heir and Bitcoin billionaire Matthew Mellon, ex-husband of Jimmy Choo co-founder Tamara Mellon; he said it cured him of his opioid addiction.

Meanwhile ketamine, which at certain doses is used as a general anesthetic for children (and as a club drug by slightly older children), is already available by prescription for treatment-resistant depression. MDMA (aka ecstasy or molly) has been used illegally in psychotherapy for decades, but it can now legally be given to select patients with PTSD outside a clinical trial—even though it’s still a DEA Schedule I drug “with no currently accepted medical use.”

Compass Pathways, the London company testing whether psilocybin helps with treatment-resistant depression, seems to be on the brink of something too. “The best available evidence” of whether it works, or whether previous studies conducted without a control group taking a placebo were a fluke, “will come from this study,” says Metten Somers, a psychiatrist who runs one of the trial’s 21 sites, at University Medical Center–Utrecht in the Netherlands.

“When we started researching psychedelics, other researchers attacked us,” Liechti says. “A few years later they were doing the same type of research.”

Jennifer Mitchell, an associate professor of neurology at the University of California San Francisco, was a grad student in the early ’90s when she approached the head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the time, Alan Leshner, at a conference. Mitchell had heard reports that ibogaine showed promise in treating opioid addiction with a single dose. “Would you consider allowing researchers to have access to ibogaine for our experiments?” she asked Leshner. Mitchell says he looked at her over the top of his glasses and said, “Frankly, neurotoxicity is bad for you.” (“My view,” Leshner says now, “was that if the data shows something is clinically useful, I’m happy to follow the science.”)

“It demonstrated shortsightedness,” Mitchell says over lunch at a Thai restaurant in Berkeley. She has just come from a meeting with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, about a project it’s sponsoring on treating PTSD with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy; Mitchell is a site principal investigator in the study. Her journey from naive grad student to researcher navigating the politics of Schedule I drugs to published neuroscientist studying them is the story of how psychedelics have evolved, in society’s eyes, from an evil into one of science’s best hopes in treating classes of mental illness that are growing throughout the U.S. and for which the number of consistently successful treatments is approximately zero.

Mitchell grew up in a working class area of San Francisco in the 1970s, a time when the city was experiencing a surge in mental illness. “A lot of people had been in Vietnam,” she says. Also, traumatized refugees from wars in Central America were streaming into the city. “I saw a lot of people struggle, a lot of suicide and depression.” Mitchell became fascinated with how some people could experience trauma and be resilient, while others fell into mental illness; she decided to make a career out of trying to figure out why.

Discouraged by her encounter with Leshner, Mitchell spent years researching the neurological pathways of addiction. In 2017 she heard that MAPS had money for a trial of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy and attended a meeting of investigators. MAPS had for a while been considered on the fringe of mental health research, but at the meeting she found “very smart, driven, type A women,” some with experience developing drugs for Novartis. Mitchell decided to try to work with them. “I’m not a true believer” in psychedelics, she says. “I was not trying to prove a thing I thought I already knew.”

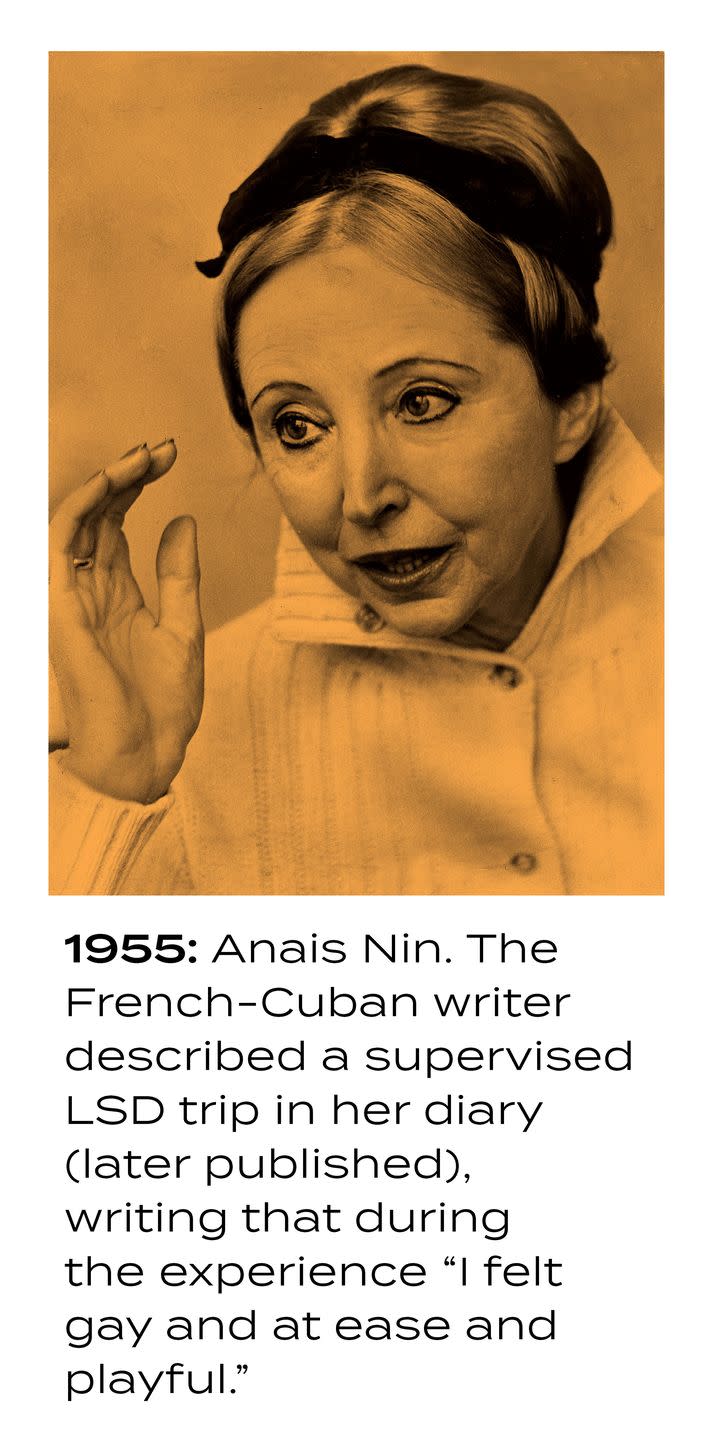

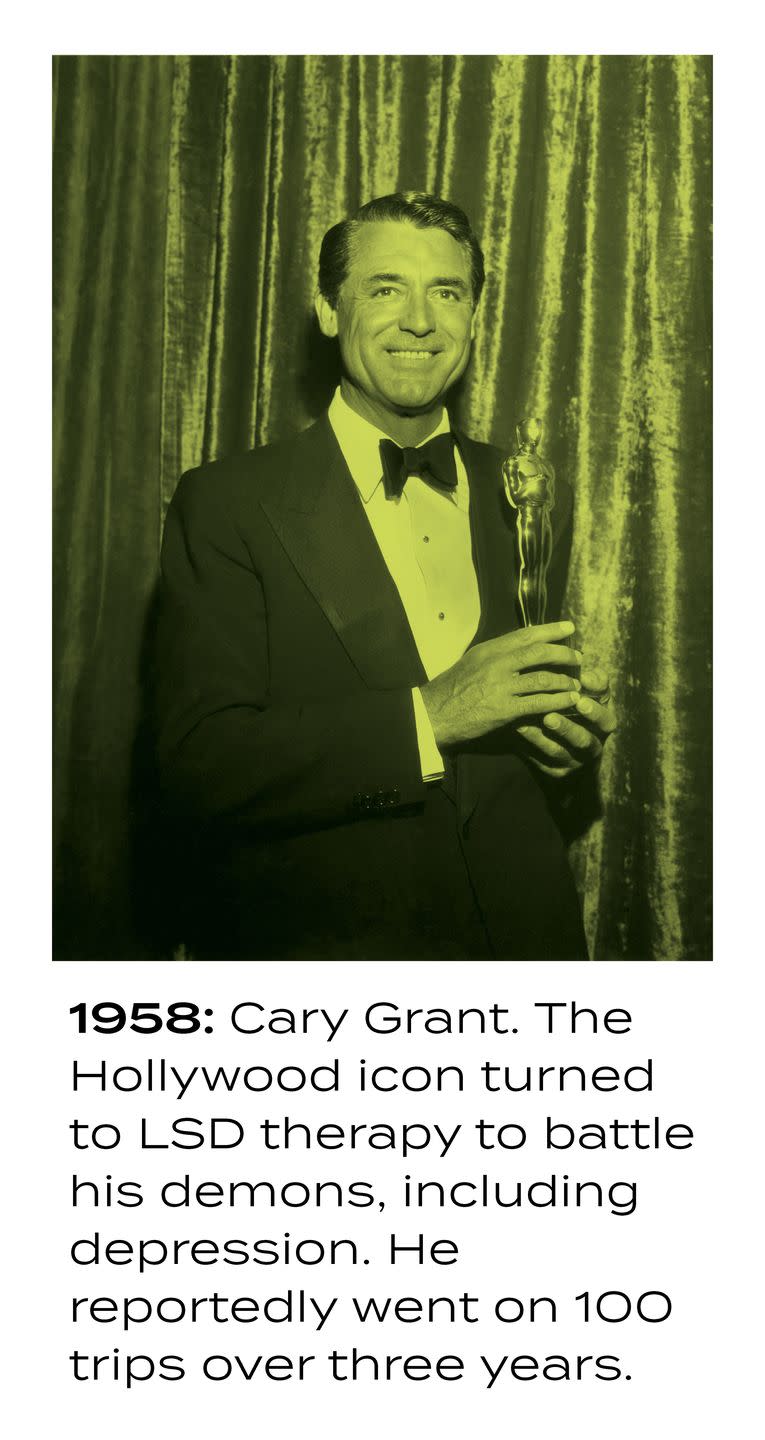

In the first couple of decades after Hofmann discovered LSD, many researchers believed—maybe a little too strongly—that it had potential as a therapeutic. Michael Pollan’s 2018 book How to Change Your Mind details the early history of research into psychedelics.

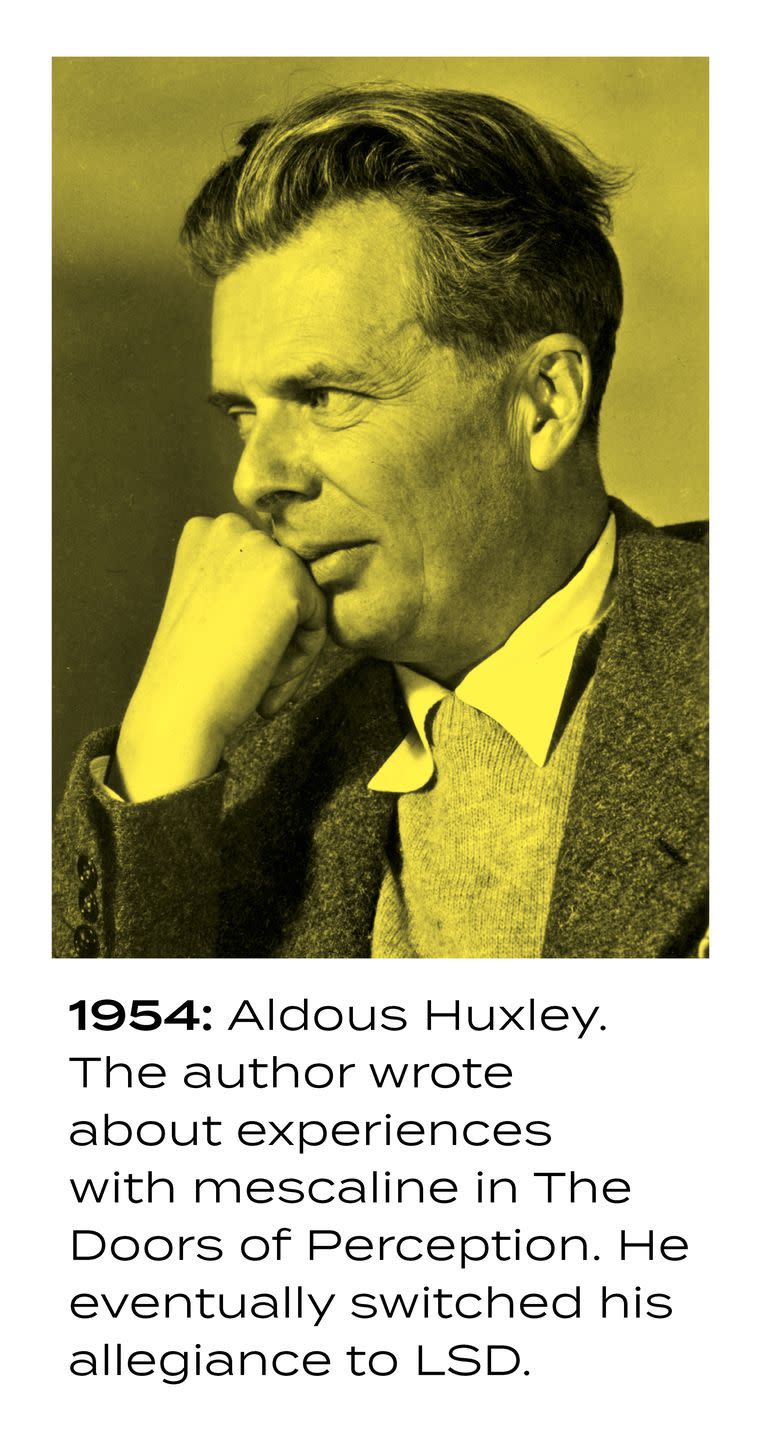

In 1953, British author Aldous Huxley took mescaline, a compound that occurs in peyote and other cacti and has effects similar to those of LSD, and he described his experience as overwhelmingly positive. Two years later Manhattan banker and mushroom fanatic R. Gordon Wasson traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, having heard reports from a Harvard ethnobotanist of a species that caused “visions.” He wrote up his experience in Life magazine.

Reading reports that sounded similar to descriptions by the severely mentally ill of what was going on in their minds, researchers began to wonder if what drove mental disorders was chemistry—a question that eventually led to the development of Prozac and other antidepressants, which have helped millions. By 1961 researchers at Stanford and other universities were studying the effects of LSD and mescaline on healthy volunteers under permits from the FDA.

Could these compounds be the key to unlocking the mysteries of psychosis? Sandoz supplied LSD to researchers all over the U.S., from Maryland to California, and Hofmann would go on to identify psilocybin as the active ingredient in magic mushrooms and synthesize it.

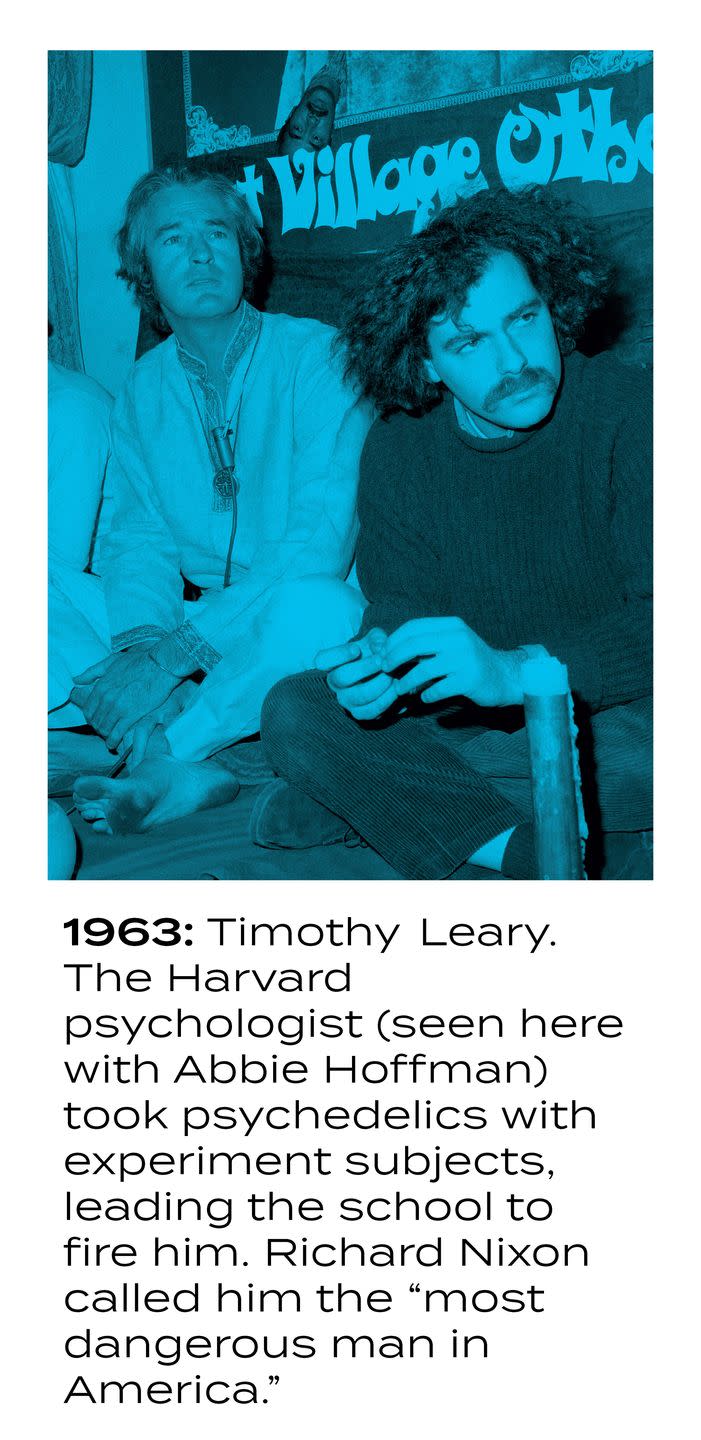

But psychedelics would quickly spill out of academic and institutional control. In 1960, LSD started showing up as a street drug. The same year, Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg took mushrooms together. Leary and a colleague (Richard Alpert, aka Ram Dass) began to evangelize about psychedelics and their potential to expand human consciousness.

As hundreds of thousands of young people decided to see for themselves, media reports, many of them false, started telling horror stories about kids who had taken the drugs and ended up in hospitals, or dead. In 1966, Sandoz withdrew its supply from scientists, and the FDA ordered 60 psychedelic researchers to halt their work. The first wave of psychedelic research came to an abrupt end nearly everywhere. California banned LSD that year, and the federal government followed in 1970.

MAPS was founded in Santa Cruz in 1986, the year after MDMA was made illegal. (Many people don’t consider ecstasy a psychedelic, since it acts on different mechanisms in the brain, but it can have effects on certain mental health conditions similar to psilocybin’s.) Getting anyone to take seriously MAPS’s assertion that the drugs ought to be studied was very slow going in the early days, especially in the face of untrue coverage, such as a documentary MTV aired in 1985 in which it was claimed that MDMA caused “holes in the brain.”

Then, in the 1990s, Bob Jesse, an engineer and executive at Bay Area software company Oracle who had experimented with psychedelics, uncovered more than 1,000 scientific papers on psychedelics published during the first wave.

When scientists started looking at psychedelics, it was for insights into the mechanisms of mental illness, but they soon discovered that the substances could also be cures. Psychedelics had been studied as treatments for alcoholism, depression, anxiety, and OCD, among other conditions. Though not well designed by today’s standards, many early studies showed impressive results.

Moreover, there appeared to be no such thing as a lethal dose—something that cannot be said even about many over-the-counter medications. People who freaked out and went to a hospital after taking too much acid walked out several hours later. Wellness guru Andrew Weil, volunteering at the Haight-Ashbury Free Clinic in 1968, developed a protocol for San Franciscans on bad trips: Leave them alone.

Shortly after Jesse found the documents of decades of fruitful research, a psychiatrist named Franz Vollenweider, working at the Zurich hospital where schizophrenia had first been described, in the 1950s, discovered in 1998 how psilocybin acts on the brain: It activates a receptor of serotonin, a brain chemical involved with mood that is a target of antidepressants. Hofmann himself had encouraged Vollenweider to go to medical school after he stumbled, as a biochemistry student, across botanicals that caused dramatic effects with a tiny dose. “He said, ‘It’s better to work with humans,’ ” Vollenweider told me.

After the 2017 meeting with MAPS investigators, Jennifer Mitchell collaborated with UCSF colleagues Josh Woolley and Brian Anderson to give psilocybin to AIDS survivors suffering from demoralization. Men in San Francisco with full-blown AIDS were getting antiretroviral therapy, which for most of them transformed the disease from a death sentence into a long-term condition. But many of them had friends and lovers who hadn’t lived long enough to benefit from the advances. The survivors struggle with feelings of isolation, despair, and guilt.

Mitchell believes the medical community’s successes against the AIDS epidemic and the Bay Area’s acceptance of research into psychedelics as medicine are related. “This became a very pro-medical, pro-research community” after antiretrovirals were discovered, she says. “We have seen the value of research put into practice.”

Of course, the Bay Area, more than any other part of the country, had demonstrated its comfort with psychedelics from the earliest days, when LSD was being studied at Stanford and reports of the drug’s effects leaked out of a secret CIA experiment at Menlo Park Veterans Administration Hospital through one of its subjects, author Ken Kesey, who would go on to organize and promote the famous “acid tests” of the mid- to late ’60s, in which thousands of people took black market LSD.

That comfort never really went away. One Sunday this past January, three days after I met Mitchell, I rode shotgun with a dealer in illicit psychedelics on a delivery run. We met at his house, a Victorian a few blocks from where the Grateful Dead lived together in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood during the Summer of Love. We stopped for coffee and gas and hit the 101 South, toward Santa Cruz.

A few years ago the dealer, a graduate of a Bay Area university and former corporate executive I’ll call Rafe, took some mushrooms recreationally at a concert. He happened to meet the fungus’s grower, who lived in a rural area far to the north and had been looking for someone to move the product in the Bay Area. Soon Rafe was acquiring from this source five strains of mushroom, along with mescaline, 500 doses at a time. He had no trouble unloading it.

As his ancient 4X4 swerved along the highway through the redwood forest that divides Silicon Valley from Santa Cruz, Rafe told me his customers are not teenagers, taking the drugs to get high, but adults, some as old as 65, seeking a therapeutic experience. Over the last several years a trend known as “microdosing” has taken hold in Silicon Valley among programmers and others who find that psychedelics improve their focus and creativity.

Their anecdotal reports drove MindMed’s interest in testing LSD as therapy for ADHD. But Rafe’s customers that I spoke to are finding in small doses of psychedelics relief from anxiety, depression, and PTSD—precisely the conditions for which Mitchell and others are testing the effects of psychedelics in larger doses and in conjunction with psychotherapy.

Psilocybin “has medicinal value, healing properties that are mental, spiritual, emotional,” Rafe said. He has struggled off and on with depression since his twenties. “I had to navigate these things myself over the years, so I like that I can help people. I feel I’m doing a service to the community. To have someone with crippling anxiety say, ‘Oh my god, I can function and not have a constant sense of dread’ is very rewarding.”

Rafe parked the car at the waterfront, and we walked past the carnival rides, across the beach boardwalk, and out onto the pier. His customer appeared: a man in a zippered hunting vest, Carhartt beanie, and Jimi Hendrix T-shirt. Both now middle-aged, the men have known each other since college. Tacos were called for. They stepped inside the Dolphin restaurant as surfers caught the last breaks of the day.

The customer, whom I’ll call Brian, is a recovering alcoholic. “Having depression return in sobriety, that’s brutal,” he said as Rafe sipped a nonalcoholic beer. “You’re doing everything right, but you feel fundamentally, personally deficient.” Brian, like Rafe, took his share of psychedelics recreationally in his late teens and twenties. But at low doses it’s therapeutic, he says. “Psilocybin at higher doses is pretty much an ordeal, but it’s almost best when you can’t notice it.”

He pauses and looks out at the surfers silhouetted by the setting sun. “Really, I’m doing it so that on Monday I will have done it. You don’t need to know it’s happening, but it’s there, and it works.” He has found that if he takes it regularly “it’s 100 percent effective at keeping the ever lurking depression at bay.” He’s not the only person who thinks so; a 2015 paper in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that off-label psychedelic use was associated with reduced psychological distress and suicide.

As Brian and other customers of Rafe’s consume psychedelics illegally, evidence of the drugs’ positive effects in scientific trials is piling up. “Research into psychedelics might identify novel therapeutic mechanisms and approaches”: Franz Vollenweider et al., Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2010. “Depressive symptoms were markedly reduced three months after [a single] high-dose treatment with psilocybin with psychological support”: Robin Carhart-Harris et al., Lancet, 2016. “MDMA-assisted psychotherapy had a greater effect on PTSD than prolonged exposure therapy, its most widely accepted treatment”: Timothy Amoroso and Michael Workman, Journal of Psychopharmacology, 2016.

There is much that needs to be worked out before your doctor will be prescribing a session of psilocybin in the presence of a psychiatrist in a softly lit room, with a van Gogh print on the wall and spa music emanating from an egg-shaped speaker, like the one at University Medical Center in Utrecht that I visited. What is the role of the therapist? How much should he or she be involved? “Is music really required?” asked Josh Woolley, who works with Mitchell on the study of psilocybin-assisted therapy for AIDS survivors. “Should you do more music?” There is no end to such questions.

Some people, including MindMed’s Rahn, worry that the efforts to legalize psilocybin underway in California, Oregon, and the District of Columbia could be a threat to researchers’ access to the compounds in the future. “These are medicines, but if there’s a backlash against state legislation, it could shut down the research,” he says. And the drugs are not without risk: People with a history of psychosis or at risk of schizophrenia are currently excluded from trials. Ibogaine evangelist Mellon reportedly died of a heart attack after taking ayahuasca, a plant containing the psychedelic compound DMT, as part of a therapeutic regimen.

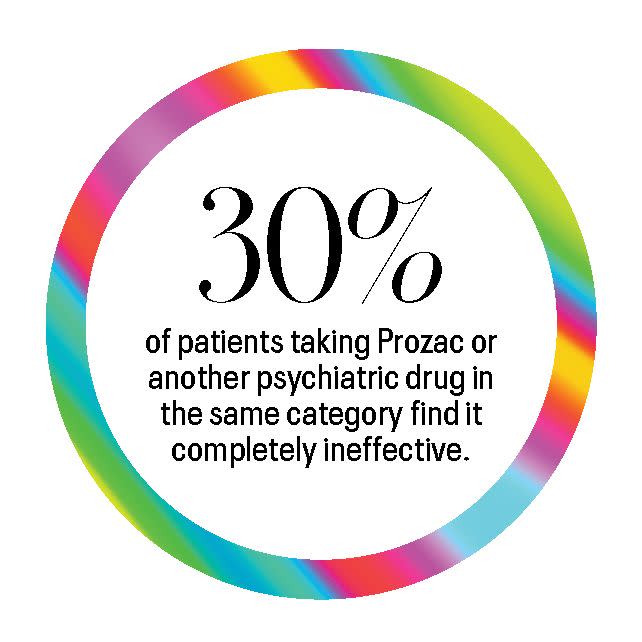

Still, in light of the fact that the latest class of psychiatric drugs, a category that includes Prozac, are ineffective in 30 percent of the patients who take them, and rates of serious mental illness and suicide are climbing, it will be hard, as the data accumulates, for the FDA to deny patients access to psychedelics—whatever middle-aged guys are selling on the Santa Cruz wharf.

“When I was a resident, if someone had told me there could be a treatment you could take once and immediately feel better from severe depression,” Woolley says, “I would have said that’s impossible.”

“We’ve got a path,” Mitchell says. “It’s pretty clear. We just need to follow it. The data will speak for itself.”

This story appears in the May 2020 issue of Town & Country.

You Might Also Like