Tick season is kicking off early this year — experts warn of Lyme disease risk

Ticks are emerging earlier than usual this year, experts warn, and we could be in for a severe season.

The parasites are typically most active from April to September, but New Hampshire health officials have already started fielding reports of ticks. And one Minnesota county reported its first deer tick of the year in early February. Blame the uptick on the mild end to winter.

The New York State Department of Health explained that ticks can be active when outdoor temperatures reach 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

“As the weather gets warmer, New Yorkers are naturally spending more and more time outside. Because ticks can be found outdoors in most areas of New York, we want to make sure people are educated on how to prevent tick bites and tick-borne illnesses like Lyme disease,” State Health Commissioner Dr. James McDonald told The Post in a statement Thursday.

“It only takes one bite from an infected tick to become seriously ill with debilitating symptoms, so we recommend that people practice some simple prevention measures to avoid being bitten and to protect their health,” McDonald added.

Estimates suggest that some 476,000 Americans may be diagnosed with Lyme disease each year. Here’s what you need to know about ticks and Lyme disease, the most common tick-borne illness.

What is Lyme disease?

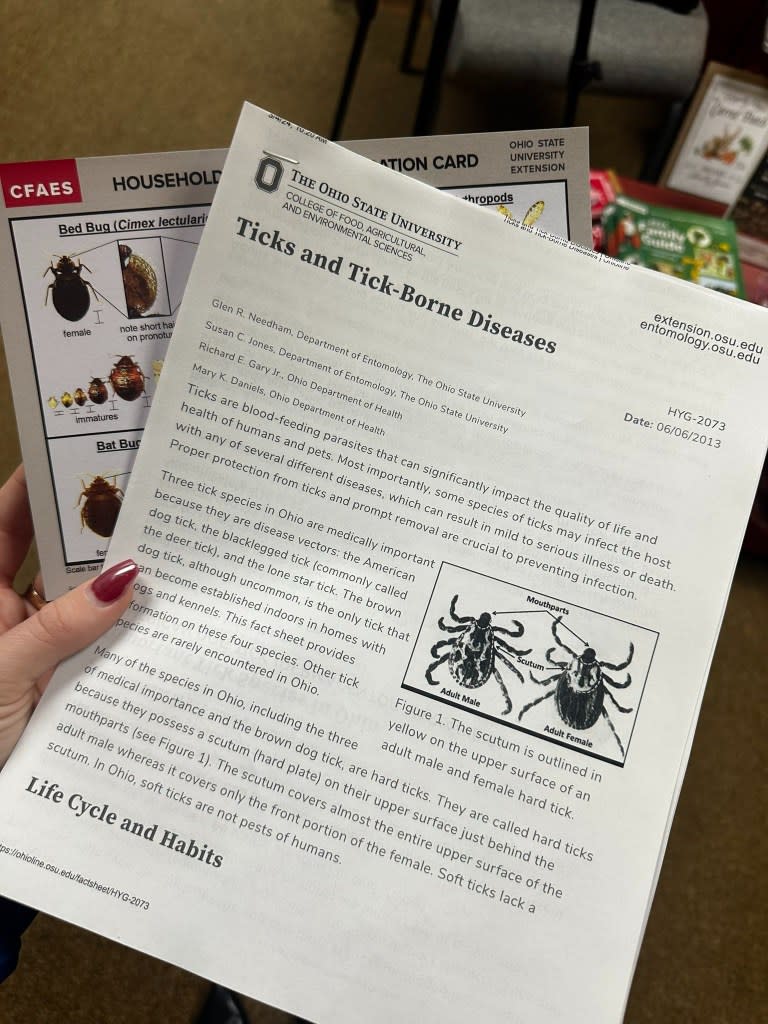

Lyme disease is a bacterial infection that’s caused by a bite from an infected blacklegged tick.

The condition, which is often characterized by a circular red rash, is most prevalent in the upper midwestern, northeastern and mid-Atlantic states. A 2022 report found that Rhode Island, Vermont and Maine had the highest incidence rates for Lyme disease, with New York placing sixth among US states.

Data for 2022 and 2023 in New York are not currently available, but the health department expects both years to show significantly higher numbers of Lyme disease than prior years because of the way reporting cases changed in 2022.

Lyme disease cases nationwide have been on the rise for decades — from 3.74 reported cases per 100,000 people in 1991 to 7.21 reported cases per 100,000 people in 2018, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The EPA blames shorter winters, which allow ticks to be active for longer, and changes in the populations of deer, which are the primary hosts for ticks, among other factors.

How do you get Lyme disease?

Borrelia burgdorferi and, less commonly, Borrelia mayonii are the bacteria that spur Lyme disease.

In the northeastern, mid-Atlantic and north-central US, Borrelia burgdorferi is spread primarily through the blacklegged tick, also called the deer tick. In the Pacific Coast states, the western blacklegged tick is the main culprit.

Borrelia mayonii is rarely found in ticks, having only been discovered in blacklegged ticks in the north-central US.

In most cases, ticks must be attached for 36 to 48 hours or longer before Lyme disease can be transmitted. Removing a tick within 24 hours can greatly reduce the risk of contracting the illness, though it’s not guaranteed.

Do all ticks carry Lyme disease?

Johns Hopkins Medicine notes that ticks are fond of yards, wooded areas and low-growing grasslands. Depending on the location, less than 1% to more than half of the ticks in the given area are carrying Lyme disease bacteria.

What are the symptoms of Lyme disease?

Symptoms can include fever, chills, headaches, fatigue, muscle and joint aches and swollen lymph nodes or rashes, according to the CDC.

If left untreated, long-term symptoms can include facial palsy, heart palpitations or irregular heartbeat, nerve pain and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord.

Early signs and symptoms can appear three to 30 days after the bite.

An early sign is an erythema migrans rash, which affects about 70 to 80% of infected people. The rash will begin at the site of the bite after seven days, on average, and will gradually increase in size. Occasionally, the bite will clear as the rash grows, creating a “bull’s-eye” appearance.

The rash is rarely itchy or painful, though it may feel warm to the touch. It may appear on any area of the body and might not always look like a “classic” EM rash.

How do you get tested for Lyme disease?

The CDC recommends a two-step blood test for Lyme disease using one sample.

If the first step turns up negative, then no further testing is needed. But if the first step is positive or indeterminate (also called “equivocal”), the second step needs to be performed.

If both tests are positive or equivocal, then the overall result is positive.

How can you prevent tick bites?

The most efficient way to protect against Lyme disease is to use insect repellent; wear clothes that cover your skin in areas with high tick populations; and check yourself for ticks.

Before you go outdoors:

Know where to expect ticks. They typically live in grassy, brushy or wooded areas, the CDC notes, or sometimes on animals.

Treat clothing and gear. Use products containing 0.5% permethrin, or buy clothing and gear that’s already been treated with permethrin.

Use EPA-registered insect repellents.

Avoid contact with ticks by steering clear of wooded and brushy areas with high grass and walking in the center of trails.

When coming indoors:

Check your clothing for ticks, and remove any ones you find. Tumble dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill any remaining ticks, the CDC recommends.

Examine gear and pets.

Shower within two hours of coming indoors.

Conduct a full body check after being outdoors. Be sure to check under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, the backs of knees, in and around hair, between the legs and around the waist.

Prevention remains the most effective method to protect yourself and others from being bitten by an infected tick, New York health officials say.

Is Lyme disease treatable?

Those treated with the proper antibiotics in the early stages of Lyme disease typically recover quickly and completely, according to the CDC.

Regimens for the erythema migrans rash, the most common manifestation of early Lyme disease, include amoxicillin, doxycycline and cefuroxime.

Facial palsy can be treated with oral antibiotics (doxycycline) and Lyme meningitis/radiculoneuritis can be treated with either oral or intravenous antibiotics (doxycycline or ceftriaxone), depending on severity, the CDC says.

Lyme carditis — when Lyme disease bacteria enter the tissues of the heart — can be treated with oral or intravenous antibiotics, depending on severity. Some patients might require a temporary pacemaker. Antibiotics include amoxicillin, doxycycline and cefuroxime for mild cases, or ceftriaxone for severe cases.

An initial episode of Lyme arthritis — when Lyme disease bacteria enter joint tissue and cause inflammation — is treated with a four-week course of oral antibiotics (amoxicillin, doxycycline and cefuroxime), though some may require a second course if the issue persists. Intravenous ceftriaxone is preferred for the second course for those who had no response to the initial course.

Be sure to consult with an infectious disease specialist when it comes to individual patient treatment decisions.

Is there a vaccine for Lyme disease?

A vaccine for Lyme disease is not currently available, but clinical trials of new vaccines are underway.

Pfizer and Valneva have developed a vaccine candidate — VLA15 — that’s already in Phase 3 human trials, the CDC said. Moderna also has candidates for mRNA vaccines against Lyme disease, with mRNA-1975 in clinical development and currently in Phase II.

In 2002, the only vaccine available for Lyme disease, LYMERix, was pulled from the market and discontinued by the manufacturer due to “insufficient consumer demand,” according to the CDC.

Demand reportedly decreased due to adverse effects such as arthritis as well as general anti-vaccine sentiments, but the FDA found “insufficient evidence to support a causal relationship” between the effects and the vaccine, researchers concluded in the Epidemiology & Infection journal in 2007.

The removal of LYMERix, made by SmithKline Beecham, left people without alternatives besides antibiotics after a tick bite, and drug makers wouldn’t make a new vaccine due to potential market risk, Nadine Bowden of the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases told Axios last year.

Aside from the vaccine, researchers have been looking into other alternatives to protect against Lyme disease, including a human monoclonal antibody as pre-exposure prophylaxis for Lyme disease and more sensitive tests that look at biomarkers the body releases when it has Lyme disease, as well as vaccinating mice in tick-infested areas with the hopes of spreading the immunity to the ticks themselves.