I Thought I Got Dispatch's "The General." Then I Heard The Song in Russian.

Chadwick’s Parents’ Living Room, West of Boston, 1996

Chadwick had a new song to play for us.

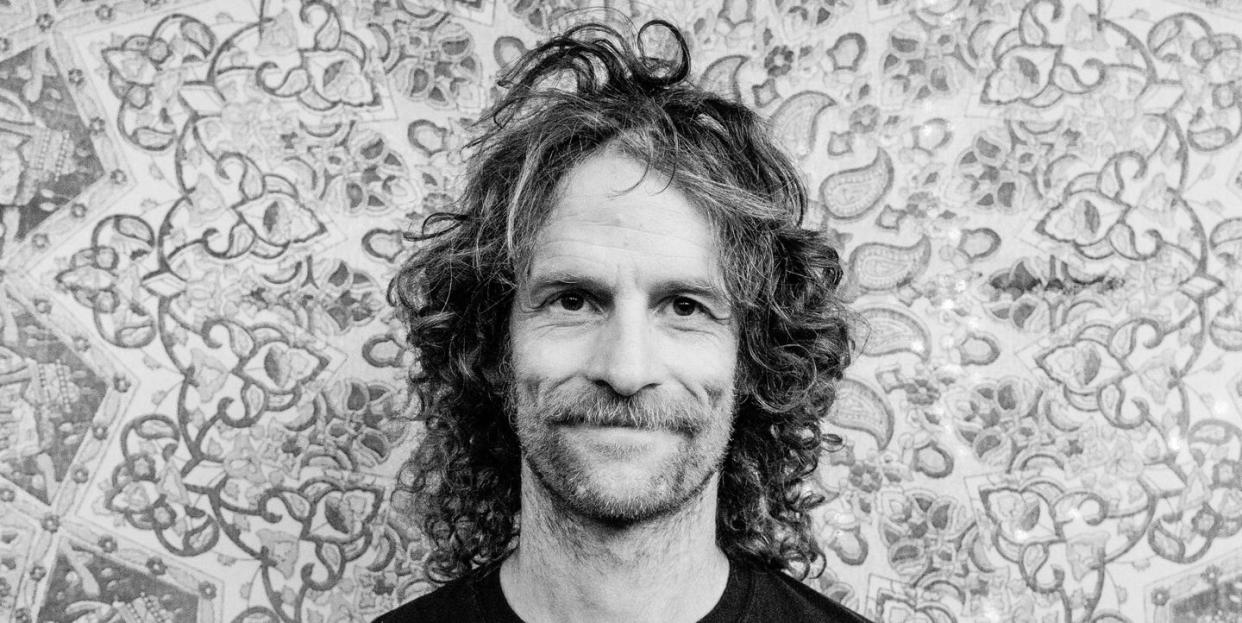

I always loved this, existing as I did on the outskirts of his prodigious talent, looking in. The fire was dying, and there were just a couple of lamps on in the room. It was late. He picked up his sister’s Phantom acoustic guitar, the one with the wood worn away around the sound hole from years of hard strumming. He stuck a pick in his teeth while he tuned. He flipped a page of his spiral notebook, looking for the beginning of the notes he’d been working on that day. His bandmates—Pete Francis and Brad Corrigan, all of us friends—and I sat and waited.

“Let’s seeeee, how’s it go,” he said. “Okay.”

Then he played. His fingers moved fast, and I smiled right away because it still looked like magic to me, all those notes tumbling out so quickly. He and Pete and Brad had been trying to teach me to play on the new Yamaha I’d recently bought at Sam Ash for $149. (I used to scratch at the body with a pick, around the sound hole, trying to make it look old and worn from years of playing, like Chadwick’s. So embarrassing.)

Then he sang: “There was a decorated general with a heart of gold…” The lyrics were a little different then, still inchoate, but the story was fully formed: an Army general who sees in a dream that the war he’s fighting is pointless, and instructs his men to leave the battlefield, go home, and live their lives. (At the end, there was a verse in which the general walked onto the battlefield alone and gets gunned down by the enemy; his men, still lingering in the area, recover his body and bury it—a verse that didn’t make it into the final song. Some trivia.)

The lyrics spilled out of him in a fury. It was like Chadwick was trying to keep up with his own song. I can still see him, sitting on his parents’ couch in the lamplight, singing as fast as he could—“he-grew-a-beard-as-soon-as-he-could-to-cover-the-scars-on-his-face…”

I got chills.

The band was Dispatch, and I was their manager. I wasn’t the world’s greatest manager, at least in the traditional sense. I admit that. I collected the money at the end of the night after gigs, and drove the long shifts in the van, but I like to think the value I added was intangible, more emotional and psychological than, you know, managerial. Also, I was always on time.

Chadwick finished playing the song. I said what I always said, because it was always true: It was amazing, it was beautiful, I loved it. But here’s the thing: Of all the first times I’ve heard Chadwick play a new song over the years—except one a few weeks ago when he broke a string on my guitar—I don’t remember any other first time in the same detail as I remember the first time he played “The General.”

On-Campus House, Vermont, 1997

Six of us lived in the house, behind the dining hall. There was a small living room, with a working fireplace and a taxidermy goat’s head over the mantle. One of my housemates, a brother to this day, had his girlfriend visiting from another college that weekend. Pete, Brad, and Chadwick were playing in our living room, for about a dozen of us, sitting on the floor and draped over the questionable couch someone had bought from the guys who lived there the year before.

The guys had plugged in some small amps and sang us song after song. Around midnight, the guy with the girlfriend came shuffling out of his room and said, sheepishly, that his girlfriend was really tired, and could we please shut the music down. Chadwick, as is his way, smiled and shrugged, and told my housemate they were sorry to keep his girlfriend awake.

Dispatch was right in the middle of “The General.” To this day, my friend is The Guy Who Pulled the Plug on Dispatch.

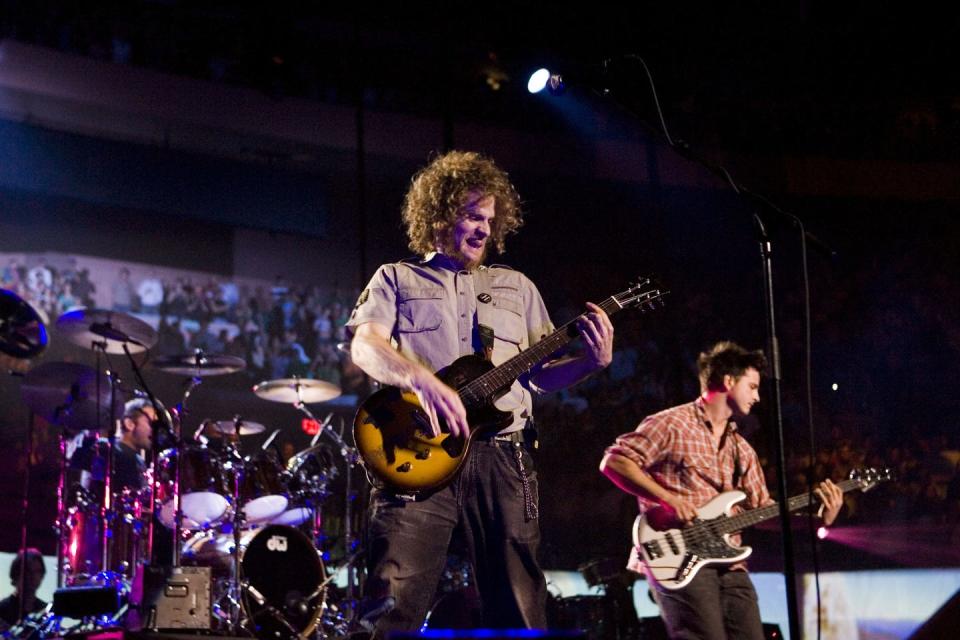

The Hatch Shell, Boston, July 31, 2004

This was it—their last concert. Dispatch was breaking up. They had t-shirts printed up: “The Last Dispatch.” As the crowd started to gather at the outdoor Hatch Shell pavilion in Boston on a sunny morning, we heard something that made us just kind of stare at each other, eyes wide: The police were estimating that the crowd could total 7,000 people.

Whaaaaa? We freaked out. Seven. Thousand. People!

They played. Played their hearts out. Fans kept streaming onto the grounds throughout the day. It started to look like a lot more than 7,000 people. At some point, it was announced that the Boston Police Department had to shut down Storrow Drive, a main artery through the city, which ran next to the venue. Storrow Drive! Shut down because of Pete, Brad, and Chad! Things started to feel weird, but good-weird. We heard during the show that the Red Sox had traded Nomar Garciaparra, our beloved shortstop—but somehow, strangely, that felt like good news. Like something was happening.

After twenty-six songs, they came back out for an encore. Everyone knew what it would be, of course. “The General.” I, along with a couple of other friends of the band, skulked up the steps leading to the stage, and watched them play it from behind them, an extraordinary sight. We were the buddies, the hangers-on, the vicarious ones—Sal shambling along after Dean in On the Road, exploding across the stars like fabulous yellow roman candles. The crowd bobbed up and down in unison splashed with sweat and beer, singing Chadwick’s lyrics, boats out on the Charles River listening in, police lights in the distance, everybody bouncing, bouncing, bouncing.

The next morning, the Boston Police Department released an official estimate of the crowd: 110,000 people had heard Chad sing “The General.”

Also, the Red Sox won the World Series that year for the first time since 1918.

Also, this was not the last Dispatch concert.

Madison Square Garden, July 14, 2007, Afternoon

The place was empty. I was sitting on a folding chair in a sea of empty folding chairs, deep on the floor. My friends Pete, Brad, and Chadwick are on the stage. I was sitting on a folding chair in Madison Square Garden. The world’s most famous arena. I’d seen Springsteen there, and Phish, and many Rangers and Knicks games. And now…we used to ride around in the van together, the four of us—me driving, those guys sleeping or playing guitar in the back or half-arguing. Pissing in empty Gatorade bottles.

We were in Colorado once, and they bought me cowboy boots at an outpost that Brad said was the real deal. (Brad’s from Colorado.) We were in Illinois once—just me, Pete, and Chadwick, because Brad had broken his tailbone in a snowmobile accident, so we’d had to cancel a gig in Nashville—and I was driving, and the transmission dropped out of the van right there on Highway 70, middle of the night, and the tow-truck driver was smoking butts right in the cab with us, windows up, and we ended up staying in Effingham for three nights while a guy replaced the transmission, in one of those plazas near the highway, eating Steak ‘N’ Shake, bowling, and going to the movies.

I sat out in the chair watching sound check. Chadwick’s brother Ben came over. We just looked at each other and shook our heads and laughed. There they were up there, playing pieces of songs, getting the levels right. “There was a decorated general with a heart of gold, that always likened him to all the stories he told…”

February 2022

My family and I were visiting Chadwick and his family near Boston. There aren’t many families we can visit, because my younger son is in a wheelchair and has medical needs, day and night. But Chad and his wife worked many summers at a camp for disabled people, so for them it’s no big deal. They can transfer him to and from his bed and his wheelchair. They can feed him. They can push his medications through the tube in his stomach. And most important, they can make him—and us: me, my wife, and our older son—feel like it’s no problem. They make us feel normal.

Chad showed me the studio he built above his garage: all reclaimed wood and cool angles and big windows. We both like doing projects like this, and he showed me all the work he did himself, until we needed to head back down the stairs to the street below, where our children were scrambling around playing hockey and riding bikes and chasing each other under the street lamps, in the endless glow of a childhood evening, when all that matters is the sound of laughter and the tears at the corners of your eyes from the wind and the fun that seems like it will never end.

April 25, 2022

Chadwick told me a few weeks ago he was going to try to record “The General” in Russian. I said something like, “Cool,” and we didn’t talk about it much more.

And then I get this video sent to me by the Dispatch team. It’s Chad, in the studio above his garage, singing “The” freaking “General” in freaking Russian. Like: He learned it in Russian. The idea is pure: Imagine every Russian general dreaming this same dream, and ending the war in Ukraine.

Chadwick, and the band, by now have a long history of helping others. They’ve played benefits to raise money and awareness around problems including mass incarceration, poverty, and domestic abuse. The Calling All Crows organization, created in 2009 by Chadwick and his wife, Sybil, “connects music fans to feminist movements for justice and equality.” This—“The General” in Russian, in support of peace—is not out of character for him.

I thought I got “The General.” And on some basic level, I did. We all did, because it’s a well-told story. Even the college kids who shouted along at parties and music festivals, on some level, probably got it. But re-hearing it now, and seeing Chad’s fingers flicker up and down the fretboard twenty-six years later, and hearing him sing his song in a language that sounds foreign but also as natural as his own, I got chills.

You Might Also Like