The Thing That Made Bill Russell Great

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

When we talk about the history of the NBA, there’s simply Before Bill Russell and After Bill Russell. He arrived in mid-'50s, almost a decade after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in baseball. With all due respect to George Mikan and Bob Cousy, Russell was the league’s first great modern star. His career coincided with the tumultuous civil rights era of the '60s, and Russell spoke publicly against racism and oppression at great risk to his own safety and future earnings. Here’s what helped—he was the greatest winner in American professional team sports. When his 13-year career was complete, Russell was the winner of 11 championships, including two as player-coach. By the way, he was the first Black coach in the NBA.

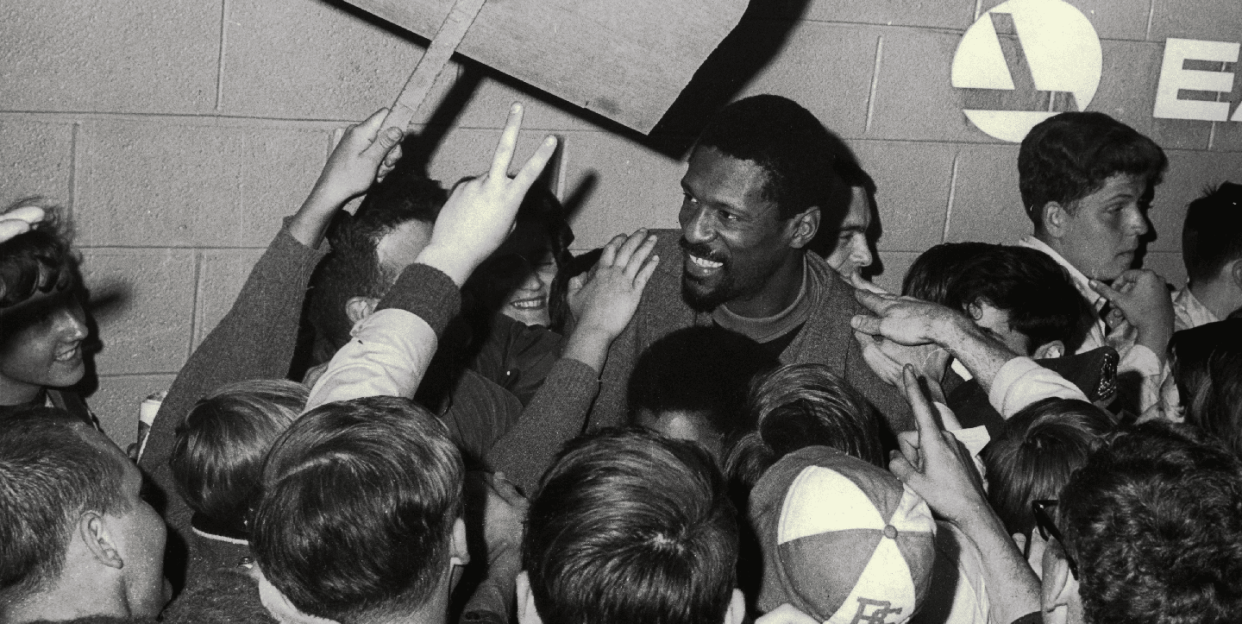

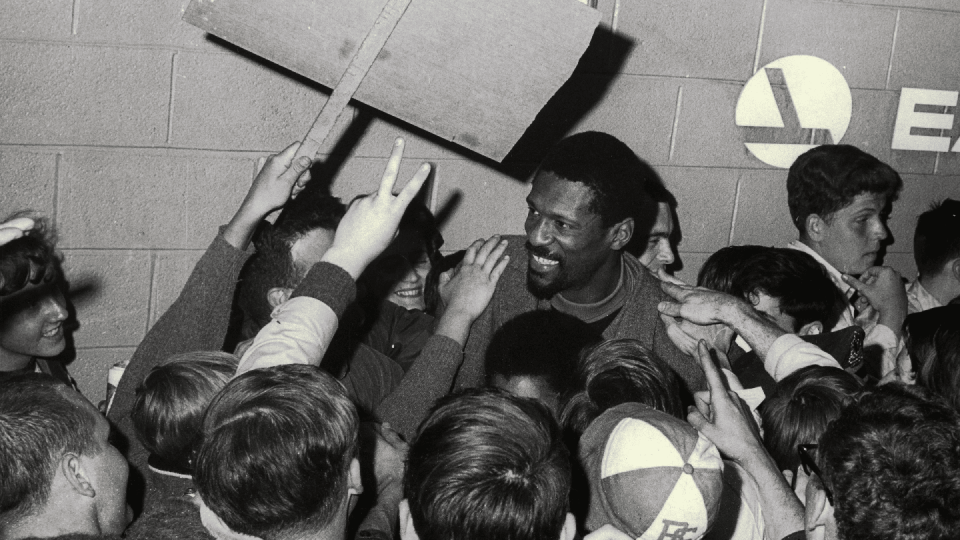

Put another way, in the reductive, voice-clearing world of sports debate: Russell has them all beat. Wilt, Kareem, Jordan, LeBron? As Jalen Rose says in filmmaker Sam Pollard’s engaging new two-part Netflix documentary, Bill Russell: Legend, Russell has more rings than fingers. But what gives Pollard’s thoughtful examination emotional heft is that despite his on court success, Russell was a probing, complicated man. Interesting and interested. And while his seriousness could be intimidating—he suffered no fools—Russell was not without a sense of humor, and, as almost anyone who encountered him will attest, had an unforgettable cackle of a laugh.

Pollard, one of our most prolific filmmakers, has been chronicling the Black American experience for five decades. He edited the seminal hip-hop documentary, Style Wars. (If you have somehow managed not to see this, now is as good a time as any to correct that.) He cut six features for Spike Lee, including the masterful documentary, 4 Little Girls. Pollard has directed stellar documentaries about Martin Luther King Jr., Sammy Davis Jr., Arthur Ashe, and August Wilson—to name a few—and now weaves Russell’s brilliant career and its impact on American sports culture, in a smart, nuanced narrative. Bill Russell: Legend reminds us that in the world of team sports, the biggest team player of them all was also perhaps the most singular individualist, too.

ESQUIRE: The great filmmaker Federico Fellini once said, “I always direct the same film.” Does that resonate with you all?

SAM POLLARD: It kind of does. If you look at my body of work, from Style Wars on, much of what I’m doing speaks specifically to the African American community, number one. Number two, in the last ten years I would say a lot of the stuff I’m doing—from August Wilson to Sammy Davis to Marvin Gaye—speaks to the unique experiences I had growing up and understand. Sammy Davis really speaks to me because I was very informed by him as a teenager; August Wilson spoke to me because in my thirties I was going to see his plays like The Piano Lesson and Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. When you even look at Black Art: In the Absence of Light, those artists I was aware of before I got involved in that film. So a lot of this stuff is speaking to me, to my particular generation and my particular experiences.

Bill Russell wasn't slick or a ham, but he was an interesting conversationalist.

What’s interesting about Russell is from one perspective, he seems like this imposing, 6’ 9 center for the Boston Celtics. Winner, winner, winner, right? But there’s the other side to Bill Russell where he’s extremely thoughtful. He’s extremely nuanced about everything in life, not only as a basketball player but as a Black man in America. And he had opinions about everything. He was cut from the same cloth as Jim Brown. And even Ali. To really speak up about things. And respond to things. And that’s what’s amazing about Russell is that he was really able to give his emotional and intellectual perspective on things. What he felt about Wilt Chamberlain in Game 7 in 1969 shows he had this side too where he says, “Well, that guy didn’t really play the best he could. I would have never come out of the game.” He had a very large ego.

What’s fascinating about Russell is that on one hand, he was the game’s ultimate champion: 11 rings. But he talks so candidly about how all that winning didn’t bring him peace. Did those 11 rings really make him a happier man in the world?

They didn’t. And you saw what he did. He wins the 11th ring in '69 and he gives it all up. He walks away from Boston. He walks away from the Celtics. He walks away from his family. He gives it all up because he’s searching. And he realized that as life was bigger than that just the bubble of basketball. And he needed to go out and savor that, and figure it out and see where else he could go with his life. Which he did.

I love the parts where you show art.

He saw art, that’s right. He saw that the notion of artistic creativity could be transferred to the basketball court. Which made him so special. The thing about the relationship that he and K.C. Jones developed at USF they were able to figure out how the game was played offensively and defensively. They studied it. I mean, Russell was a genius—an absolute genius.

But what’s interesting is that Russell’s artistry on the court was not like Pistol Pete Maravich. He wasn’t a soloist. Russell’s creativity was based on a team-first concept.

Always. That’s what made him so different that Chamberlain. I remember as a teenager having the conversation with people, “Who’s the better center?” Even as a 14, 15-year-old, I always thought it was Bill Russell because he played the game that was always about the team. As you see in the film, it wasn’t like he was going to score more points that Wilt or have more rebounds than him. But he was going to be able to contain Wilt enough so that his team could win. As Red Auerbach said, it’s always about winning.

Greatness is also about circumstance, time, place, what’s being required of you and how to transform your weaknesses into strengths. Russell achieved levels of greatness that had never been seen at that time despite the holes in his game. Was Russell the first modern superstar?

He is. He took his limitations, and he was able to use them to his best advantages. Miles Davis could not play the changes as fast as Dizzy Gillespie.He didn’t have the same kind of tonality as Dizzy Gillespie. But he took his limitations, and he created his own unique sound, which made Miles Davis in the '50s even more successful from an artistic and an audience perspective than Dizzy. He was able to create his own voice. That’s exactly what Bill Russell did. Bill Russell couldn’t shoot, but he knew how to take his defensive skills and use them to help that team. They had Bob Cousy, one of the great players of the '50s, but the Celtics did not win championships until they got the big man.

He was consistently unafraid to speak out during his career.

He as always going to be his own man. He wasn’t going to fall in line. When you listen to Earl Monroe talk about Bill? That was astonishing when Russell spoke out. As Kenny Smith says, your career could be killed at that time if you spoke out. And a lot of players do follow the mantra of just shut up and play. And Bill Russell didn’t. He always stood up. He always spoke out. That’s why when the Cleveland summit happened in '67, there was no surprise that you would see Bill Russell sit next to Ali and Jim Brown and talk about why Ali had decided not to be inducted into the Army.

Russell was famous for not signing autographs, so it’s cute in your film when Chris Paul tells the story of the time Russell refused to give him an autograph. It’s like, Stand in line, Chris, nobody gets one. Russell not signing autographs always made a lot of sense to me.

Why?

For me, if Bill Russell looked at me in the eye and shook my hand that would be more meaningful.

Than his autograph?

Yeah.

Well, I asked Steph Curry the same question—which I don’t think we have in the final cut. He didn’t quite understand why Bill Russell didn’t sign autographs because he felt—this is what Steph said—that [it is] part of his responsibility as a player. You got fans who love you. You want to make them say, "OK, I know why they love me. I’m going to sign this autograph." So he didn’t understand why Bill Russell didn’t sign autographs.

But he wasn’t about snubbing people. He just wanted to have an experience on his own terms.

Because that’s how he was. But you know, I always find it complicated. I was in Los Angeles last week screening MLK/FBI, and right before a guy came up and pulled out a magazine with my picture on it and said, “Would you sign this for me?” Now, the reaction in my head was, This is silly, why would I sign an autograph? But I signed it. I understand Bill’s logic but the point is: what’s the big deal?

And yet he didn’t seem to have any regrets, which is amazing for a human being to me.

I find life is complicated. Life is a series of ups and downs. You do have regrets. It doesn’t mean that you beat yourself on the back, but you know, I have regrets. I don’t always talk about them. I can’t imagine he didn’t have regrets. In his interview with Jayne Kennedy, she asked about his relationship with Wilt and asks if they’ll ever mend their relationship. And he doesn’t seem to care. But he did, really.

Even though you grew up following Russell’s career, after making this film, was there something about Russell that you learned about him that you didn’t know?

I learned that this guy’s more of curmudgeon than I ever thought he was, quite honestly. It’s always interesting when you dig into these people in these documentaries. You find out aspects of their lives where you say, I don’t know if I’d want to sit down that person for a meal. The little moment that was special to me in that relationship is that Wilt would invite Bill over to his house for dinner when they played in Philadelphia. And Wilt’s mother would say to Bill, “Don’t beat up my son too badly.” Those are nice moments.

You Might Also Like