There's a 2,700-mile Trail That Connects Santa Fe to Los Angeles — Here's Why It's Important and How to Visit

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, one writer delves into the history of the Old Spanish Trail and outlines how best to visit the trail today.

Getty Images

Antonio Armijo had a vision.

In 1829, at just 25 years old, Antonio Armijo set out to find a new path westward. He led a party of 60 men and 100 mules across the vast landscape between what is now Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Los Angeles (at the time of his journey, this region was still part of northern Mexico), in the hopes of discovering prosperous land for himself and his community. What he found was much larger than the 61 people who set out on the expedition. Ultimately, he created a path for hundreds of others to follow: the Old Spanish Trail.

Courtesy of NPS

“The Old Spanish Trail lets us reframe the way we think of American history,” Guy McClellan, Ph.D. and historian for the National Trails office of the National Park Service, told Travel + Leisure. “It’s important to recognize the northern expansion of Spanish culture." He explained that while many consider only the United States' migration in the 1800s (from east to west), it is more accurate to also acknowledge the “northern frontier” expansion of Mexico and New Spain.

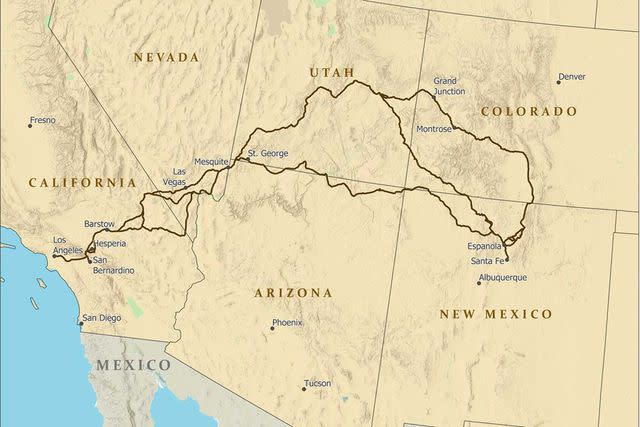

Armijo's journey, which came in at just over 1,000 miles, began in Sante Fe, headed west to Abiquiu, New Mexico, and then onto Page, Arizona; Las Vegas; Barstow, California; and finally, Los Angeles. The path used by subsequent traders eventually forked into three trails: Armijo's path, then two additional, smaller trails that head farther north to destinations like Taos, New Mexico, but eventually reconnect with the original trail. These three pathways now make up the official 2,700-mile national historic trail.

William Dummitt/Getty Images

Armijo's trek was a significant one for Hispanic heritage (though it also presents challenges for researchers, as he kept a diary some call “aggravatingly brief” about the experience), as it finally realized the long-held dream to connect Santa Fe and L.A. for trading purposes. The route was not entirely unknown to Armijo or his contemporaries. In fact, it had been traveled for years prior by Indigenous people making their way to the California coast and other Hispanic explorers attempting their own journeys west. He had the knowledge of both his ancestors and others before him working in his favor. But his efforts enabled travelers to traverse back and forth along a more direct path between (present-day) New Mexico and California, creating commerce and community-building opportunities.

“They settled in California. It wasn’t a one-and-done,” Angélica Sánchez-Clark, Ph.D., and fellow historian with the National Trails, said. “Some of the family members come back to New Mexico, and others make a concerted effort to settle communities in Southern California. [The trail] really connects these two really important places.”

As the State Historic Preservation Office of Nevada noted, “Though the Old Spanish Trail was difficult and perilous, the benefits could not be ignored.” Perils included those by Mother Nature: dangerous stretches of craggy mountains, raging rivers, and desert landscapes that could swing from sweltering to freezing all too quickly. McClellan added, one explorer wrote in their log that they encountered “deep snows and solitary gloom” and needed to get bailed out on more than one occasion by Indigenous peoples along the way.

But the landscape wasn’t the only treacherous part of the expedition. So too were the plentiful horse thieves who roamed the trail, transporting stolen stock taken from California's ranchos and missions, and those who used it to funnel Indigenous captives to New Mexico or California. “The trail wasn’t always a place of peace,” Sánchez-Clark said. But for decades, it prevailed in its mission to transport goods and people between the two cities.

However, after the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Mexico ceded the region to the U.S. The trails once used by mules shifted and instead were replaced by wagonways. Thus, the Old Spanish Trail, made famous by Armijo some 30 years earlier, was abandoned and almost forgotten — until 2002, when it was revived and officially designated by Congress as one of the country's 19 national historic trails.

Though you can’t hike the path taken by Armijo in its entirety (unless you want to walk along some of America’s busiest highways), you can visit key sections of the trail on day trips or by undertaking one epic road trip to see as many of its significant stops as you can.

Getty Images

The trail functions via a partnership between the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management, and with the help of tireless volunteers from organizations like the Old Spanish Trail Association, who maintain the trail physically and preserve it historically. Even now, some 20 years after its congressional designation, Sánchez-Clark explained, it’s a work in progress, but one her team is diligently working on to grow partnerships along the route to encourage more visitors.

For example, at the trail's starting point in New Mexico, travelers can visit the Museum of Spanish Colonial Art, which displays thousands of artifacts from before, during, and after the trail's heyday.

In California, travelers can actually walk the pathway of Armijo and his fellow trekkers in Amargosa Canyon, which is home to a vast network of hiking trails that follow the same path used by the explorers.

Those looking to feel even more grounded in the experience can also make their way to Utah to further retrace the footsteps of these brave men and women by hiking the Old Spanish Trail Heritage Loop, where they may even come across old wagon ruts and other artifacts.

And in Colorado, travelers can stop at Fort Uncompahgre Interpretive Center, a trading hub used by those traveling the trail that shows visitors an as authentic as possible recreation of the 1829 experience.

As McClellan said, “The Old Spanish trail provides an opportunity to interrogate some of the biases that we might have” and further gives us a chance to explore our collective history and some of the most beautiful stretches of our nation, one mile at a time.