How This Texan Went from Rock-Bottom Addiction to One of America’s Most Promising Athletes

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

A long time ago—before he’d freebased opioids or robbed his best friend or checked himself into rehab for the sixth time—Mitch Ammons had dreams of a future involving running.

Ammons can only shrug when asked to pinpoint the lowest point in a life filled with them. He spent a decade careening along the rock bottom, mired in what he now calls “the worst possible self-hate.”

Mitch Ammons knows his story could have ended like the stories of so many buddies from his darkest years—with an obituary. Instead, the longtime addict changed course in a manner that is, without hyperbole, beyond belief.

It’s tough to fully grasp the scale of this turnaround until you see Ammons run—to see him metronomically cruise 4:50 miles for more than an hour or to watch him push himself to the brink of consciousness in an interval session at sunrise. Then you can absorb the way he embraces suffering—relishing the revelation of what his body can do while immersing himself in pain that must feel like a cosmic body rub compared to waking up every morning in opiate withdrawal.

People who love to run know that the simple act of putting one foot in front of the other can yield life-changing consequences. It doesn’t matter if you’re running toward something or from something—embracing the activity can bring you redemption and community and purpose and confidence and inner peace. It can strengthen your quads and your mental resolve.

➡ For unlimited access to the most important stories for runners, join Runner’s World+ .

Mitch Ammons knows these things with more clarity than most of us will ever experience. Seven years ago, he was a newbie jogger who’d not run hard since the 11th grade. He couldn’t trot a half mile without collapsing. And before that, he spent a decade drowning in a sea of toxicity—smoking, injecting, drinking, popping, and otherwise ingesting every controlled substance you can think of and quite likely a couple more than that.

And now, instead of being dead or trudging through the heroic everyday chores of recovery—managing the basics to remain sober and build healthier routines—Ammons, at 34, is legitimately racing against some of the top distance runners in the country, pushing the limits of what should be possible, and living a dream that is almost incomprehensible.

Ammons will tell you himself—he isn’t a miracle or a prophet or a fairytale hero. But when you get to know Mitch Ammons, you’ll see that where a person’s been and where they’re going can be two radically different places.

Anyone can become an addict. Growing up in an affluent family, being a promising young athlete, having a vibrant social life—none of those things can protect a kid once an avalanche of bad decisions reaches critical velocity. Ammons learned this the hard way.

Before things went south, running had meant something to him. Both of his parents were runners. Though his father, a physician, quit running when Mitch was in elementary school, the man friends called Doc Ammons liked to pore over high-school track-and-field recaps in the newspaper and watch elites race in the Olympics. Mitch loved that about his dad. His mother, Alma, ran into her 40s. Riding his bike next to his mom as she jogged around their suburban Dallas neighborhood and seeing her finish races like the Boston Marathon made an impression on the kid. He imagined a destiny as a miler.

Wherever Ammons went, he always had a smile and a way to bring a smile to those around him. His mom recalls a time when he was young and came home from school and said that someone there had told him that everyone has a gift. He wanted to know, what was his gift? “Your gift is that everybody likes you,” Alma replied. Everybody who knows Ammons knows this is true. Maybe the only person who didn’t know it back then was Mitch.

He took up track in fifth grade. Soon, he was demonstrating obvious if unremarkable ability. Competing for a Catholic school in the Dallas Parochial League, he was winning a few events at every meet by the seventh grade. His coaches and dad took note of his perfect, compact stride. The next year, he ran a 4:52 mile and was named MVP of the season-ending city meet. Ammons says these results were not the product of hard work; he admits now that he never did any real training in his first running life.

After that, his running teetered on a plateau before falling into the abyss. First there was the alcohol. And by seventh grade, Ammons was smoking weed. Neither is uncommon, but in his case, these were just hors d’oeuvres. “By freshman year, I had tried pills, ecstasy,” Ammons recalls. “And then I tried cocaine and Xanax.”

Mitch and his buddies started to get in legit trouble—curfew violations, possession charges, reckless driving. Before long, he was calling drug dealers as he walked toward the parking lot after Friday classes ended, cueing up supplies for the weekend.

“I started because I thought it was cool.” Ammons says. “I wanted everyone to like me, so I always made sure I was the life of the party.” The kid everyone loved to be around couldn’t see it himself.

It was tough to be the life of the party and a success on the track. In his junior year, he was on target to qualify for the Texas state championship. Then he got expelled from school for having drugs in his car. There were no races after that.

What still could be rationalized as a semi-typical partying lifestyle went off the rails when Ammons got to the University of Arkansas. While the school had a legendary distance-running program, Mitch wasn’t on it. He was racing toward self-destruction.

As Ammons recounts these years, there are no bittersweet memories of good times or playful hijinks. He started dabbling with opiates and before long he was freebasing Oxycontin, burning tablets on tinfoil and inhaling the smoke through a straw. “It is such an intense high but also a very intense withdrawal,” he says. “I smoked a little crack as well—it’s like that, too.”

Heroin was next. It’s cheaper than Oxycontin, and the high is pretty similar. He began by snorting what they called cheese—black-tar heroin mixed with pulverized Tylenol PM tablets.

Soon he was shooting up. “I always had a line I wasn’t gonna cross, and then I crossed all of them,” Ammons says. At one point, he found himself somewhere in Arizona where it was tough to score his drugs of choice, so he started buying and smoking crystal meth. All the while he was drinking heavily, taking Xanax daily, going through a constant cycle of use and withdrawal.

The list of substances doesn’t capture the soul-crushing reality of Ammons’s addiction. He would wake up and stagger to a bathroom to vomit and then stagger back to his room to smoke or inject something to escape the misery of withdrawal. He was chilling out in crack houses. He saw a double-digit number of friends and fellow addicts die because of drug use, health issues, car wrecks, violence. It weighs on him heavily now that he cajoled friends to try or buy drugs. “I was so selfish when I was an addict,” he says. “I didn’t care who I ran over.”

Ammons’s best childhood friend, Trevor Masters, says Mitch looked death in the face many times. “There was a time when you could really see all the bones in his face,” says Masters, who rolled with his buddy on many drug-filled adventures before getting sober himself. “He robbed me, he robbed every friend when he had the chance, he robbed his parents, he did it all. He tried every which way to kill himself.”

His mother says she didn’t have a real handle on the depth of her son’s problem until his college years, when she discovered a bag of syringes in his room. “I’d read obituaries of young people, and I kept thinking that one day I’d read his name,” Alma says. “I had thought the sky was the limit for him and then I was hoping he’d stay alive.”

Ammons went to rehab six times. At the beginning, he discovered that rehab was a great place to meet other addicts who would make fruitful coconspirators for future scores. He also discovered that the stints of sobriety that would follow rehab were a convenient time to do a ton of gig work to build a war chest for the next binge. One time he stayed clean long enough to save $7,000, then wound up injecting, smoking, drinking, and popping it away in 10 days.

Throughout this ruinous decade, Ammons sometimes dreamed about running. He wondered if he could get fit enough to run a five-minute mile like he had in eighth grade. He thought about being healthy and turning his life around, but the cocaine and the heroin and the Xanax and the meth and the booze and Oxy had too much gravitational pull to resist.

The final relapse happened during his last rehab stint in 2015. Deep down, he knew something had to change—but he also was edgy about going cold turkey in rehab, so he snuck in a few days’ worth of heroin. Staff caught him nodding off in bed with his paraphernalia strewn about. “If I’m honest, I wasn’t sorry I did it,” he says. “I was sorry I got caught.”

Afterward, Ammons uttered promises he’d made and broken before. Yet this time something was different. He was older; he was desperate; maybe he was ready. He had burned through his money and friends and family and recognized that his quest to be the life of the party had become a bottomless affliction. Though he almost got kicked out of the facility for that stunt, one of the counselors had a sense that Mitch was ready to quit. She gave him another chance.

He hasn’t used since.

By 2016, Ammons was living in Austin, Texas. At the time, he wasn’t thinking about getting back into running. He was coming off a decade of addiction, still chain smoking and eating crap, just trying to avoid drugs one day at a time. He had moved in with Trevor, his best childhood friend, and was working as a waiter at a Tex-Mex restaurant. Ammons had always loved dogs, and now he had a female yellow lab named Jonnie.

It’s often tough to pinpoint the headwaters of a life-changing obsession, but in Mitch’s case it can be traced to a desire to have a girlfriend. He lived downtown and often walked Jonnie along the river and took note of all the women enjoying active pursuits. But when he articulated his interests to his buddies, they opined that fit, go-getting, sporty women are more likely to date fit, go-getting, sporty men rather than sedentary chain-smoking, cheeseburger-gobbling recovering addicts. Maybe they had a point.

One day in 2016, he was walking Jonnie and saw a guy teaching one of those boot-camp fitness classes in the park. Ammons struck up a conversation and got the guy’s card. Mitch grins at the memory—picturing himself out of shape, with unruly hair tumbling below his shoulders, huffing on a cigarette as they chatted. He showed up for a session the next day and quit smoking that afternoon. He quickly became a boot-camp regular, and took those classes for about a year.

Mitch says he noticed his mindset changing around this time. “After a year of being sober, I wanted to see what else could happen,” he says.

That’s when his curiosity about running reemerged. It started slow. Ammons remembers leaving his apartment, jogging a half mile or so, taking a long break, and then jogging back. “That would be my whole run,” he says. “And that was very, very hard.”

But little by little, he got fitter. After a friend told him she could run 7:30 miles for a half hour at the gym, he went to the gym to see if he could do it. He wound up running 7:30 miles for an hour. “I was like, wow, I can still run,” Ammons says. Before long, he was logging double-digit mileage and not dying. He needed a new goal, so he wondered if he could run a 5-minute mile again.

Pam Hess laughs out loud as she recounts the day Ammons walked into her shop in early 2018. Hess and her husband, Ryan, had recently opened a running store called The Loop Running Supply. Ammons waltzed in with a messy man-bun and shorts that went down below his knees. He fired off a bunch of newbie questions at the shoe wall.

The new guy with the man-bun bought some shoes and wanted to join a running group. So Hess directed him to Gilbert’s Gazelles, a running program created by Austin legend Gilbert Tuhabonye, a standout Burundian athlete who survived an ethnic genocide and has since dedicated himself to advocacy for peace in his birth country and building running community in his adopted hometown. Ammons began with the slower group that gathered daily at 5:30 p.m., running mostly with high-schoolers and newbies.

Tuhabonye also has a few wisecracks about the baggy basketball shorts Ammons wore in those early days, but he could tell Mitch had latent talent. “His cadence is amazing, and I could see this right when he started,” Tuhabonye says. “He didn’t look like a runner, but he had the potential to be great.”

Lots of adults who discover the joys and rewards of running throw themselves headfirst into the endeavor, but very few do it with the single-minded intensity that Ammons showed almost immediately. By the summer, he was doing regular hour-long runs with experienced marathoners. He started going to bed before 8 p.m. and repetitively eating the same healthy foods and ramping up his mileage and his speedwork. “He was showing complete obsession,” Hess recalls. “Sometimes we would go to dinner, and he would only eat rice and then say, ‘I need to go to bed.’ He didn’t really have balance.”

Trevor, his housemate at the time, couldn’t believe the transformation. “He lived right above me, and he started getting up every day at 4:30 in the morning,” he says, shaking his head. “I had to deal with that shit.”

But the transformation went deeper than fanatical habits. Ammons also was falling in love with the running community he had found—the new friends and the friendly chatter and the shared suffering. He was finally seeing what his mother had perceived all those years ago—that people loved to be around him when he was just being himself.

“Mitch is very humble; he’s friendly to everyone,” Tuhabonye observes. “Some people can fake being full of kindness, but Mitch is not like that. I could tell he was on the right path.”

Hess recalls a situation in which she and her husband were caring for her sister’s sick puppy for the better part of a summer. The dog had survived parvo virus and now it had distemper. “We were overwhelmed,” Hess says. “We had to give it IVs constantly. And we were like, who knows how to work a needle? And so we called Mitch. He would come over a couple times a day, and helped us keep this dog alive.”

It felt good to have healthy obsessions. It might not be prudent for a typical new runner to go to bed at 7:45 and order only white rice with egg whites at restaurants and start doing two-a-day workouts and contemplate 100-mile weeks and otherwise obsess about running, but perhaps the rules are different for people who are running away from a heroin addiction.

The rate at which Ammons has improved since then is almost impossible to digest, but for those who have run beside him in that period, the incremental gains are a little easier to comprehend.

Bryan Morton met Ammons in his early days of running and was struck by his charisma, his self-deprecating sense of humor, and how “completely raw” he was as a runner. Morton, who trains with Ammons now, recalls that Mitch looked like a hippie and wore a T-shirt on the most sweltering Texas summer runs. Nonetheless, he started going out with faster groups and hanging on as long as he could. On a whim, Morton invited Ammons to join a stacked Austin squad for the 2018 Hood to Coast relay in Oregon. Nobody expected much of the new guy, but Morton says that Mitch “held his own” on a team that averaged 5:29 miles for 18 hours and finished the 198-mile race third out of 1,148 entrants.

That December Ammons traveled with Hess and some others to Sacramento to run the California International Marathon. Less than a year after he showed up at The Loop with the long shorts and the man-bun and a list of newbie questions, Ammons knocked out a 2:36 marathon.

Even within the running community, relatively few people understand the term sub-elite. In most sports, there’s a clear distinction between being a pro and being an amateur. But in distance running, blurrier lines separate world-class pros, elite runners, and sub-elites. Despite their talents and commitment and relatively fast times, sub-elites don’t hold a one-in-a-million lottery ticket and can’t make a living running and won’t represent their country in international competition. “We know we’re not professionals,” says Michael Morris, a 2:18 marathoner who trains with Ammons. “We are out running before our day jobs and we’re out here because we love it.”

Still, even at this level, nearly all runners get there on a well-trod path. They almost always start showing talent early in their high-school years (or sooner) and continue a long and grinding trajectory of improvement. They race in and after college, and over time get more competitive in longer distances. And after they’ve been running at a high level for a decade, incremental improvements come increasingly slowly and only through relentless work and luck to avoid overuse injuries. If you were to talk to men who run the marathon between 2:13 and 2:25, runners who’d likely call themselves sub-elites, this would be their resume.

Mitch Ammons tore that playbook to shreds. In February 2019, seeking more structured guidance, he began working with an experienced local coach, Jeff Cunningham.

Cunningham has a propensity to tell stories that don’t hurry to their destination (“I never met a sentence I like to say twice,” he quips). When asked how he initially appraised the capabilities of his new charge, Cunningham lyrically compares distance runners to radial tires—assessing how they’ll perform and hold up by how much the treads are worn down. “Mitch hadn’t been overtrained—he had been no-trained,” Cunningham says with his fast-paced drawl. “At 30 he had the tire tread wear of an 18-year-old, from an orthopedic standpoint. So now, at the age of 34, he can train like a 24-year-old. That is the secret sauce here.”

Suddenly Ammons was training with fast, experienced runners; and with more targeted coaching, the payoff came quickly. In June 2019, he popped a 67-minute half marathon in Duluth, Minnesota. This is not a normal outcome for someone, especially a longtime addict, who started jogging 18 months earlier. This is off the charts. Ammons says this was the morning he realized he might have something special.

Nearly every day, Ammons trained with Cunningham’s crew, the Bat City Track Club. Most of them have been running seriously for more than half their lives. They would meet for predawn long runs and speed sessions at a local track. “He was like a high-school freshman at that time—he was so enthusiastic, but he really didn’t know what he was doing,” jokes Ronan O’Shea, a 2:25 marathoner and former Bat City member. “Now he’s like a high-school senior—a really talented high-school senior. He knows a lot of things that he didn’t know then.”

Ammons’s closest training partners say that he is comically intense about workouts. “Mitch fucking loves to race,” says Morton. “It’s hard holding him back. The point for him is to see where the limit is. Every workout is like this. If his personality wasn’t so lovable, everyone would be like, ‘Dude, just stop.’”

His coach and his training partners say his ability to suffer is not normal. “One of the most undervalued and misunderstood qualities of this thing that we call talent is the ability to self-inflict physical discomfort,” says Cunningham.

O’Shea agrees. “I’ve trained with guys who are way better than him—sub-4:00-milers, for instance—but none of them can make themselves hurt consistently like he can, and bounce back and do it again,” he says. “He’s gutting himself. And unlike most people, he will come out four days later and do it again. Most people would break. I would break—I know because I’ve tried.”

Ammons acknowledges it’s something he’s working on—and something that will never cease. “For a long time, I figured I wasn’t getting anything out of [a workout] unless I was completely wiped out afterwards,” he says. “The serotonin release after I see the accomplishment—that’s what I’m addicted to now. It has helped me because I can really take myself to the well. I just do it so often that when race day comes, it’s like nothing is different.”

Ammons thinks his experiences as an addict help him endure the worst that running can dish out. “No matter how hard a workout is, no matter how miserable it is to finish a race, I’m never in as much pain or as miserable as I was when I was stuck in this prison of heroin and crystal meth addiction,” he says. “I got out of the worst possible self-hate and feelings of hopelessness, and I know that it’ll never be that bad.”

Top runners typically don’t look at it that way. “Most elite distance runners live a relatively cushy and privileged life, where we can choose to inflict some pain on ourselves,” says O’Shea. “[But Mitch] knows what it’s like to be up for days on end, high. Most people would think it’s terrible to go to sleep at 7:30 p.m., and he’s like, ‘No, it’s really terrible if the party never stops.’”

Pretty soon after that fast half in Duluth, Ammons and Cunningham started talking seriously about Mitch qualifying for the Olympic Trials. For the 2024 Games, that would require a marathon time of 2:18. It seemed like an audacious goal for a guy who not long ago had been tootling through the park in knee-length shorts. But now he was a guy with shaved legs and six-pack abs, 2-inch split shorts, and an easygoing mullet-and-mustache look. For a sub-elite distance runner, qualifying for the Trials guarantees lifetime bragging rights. “This is how the everyman can live out the pro-athlete dream,” says O’Shea. “You’re in the race with the guys who go to the Olympics, but it’s attainable.”

Mitch was unafraid to discuss his aspirations to get what his cohort calls an OTQ. He has a modestly large Instagram following, and he has used the platform to celebrate his physical and metaphysical transformation. So, not surprisingly, his story became well known in Austin and among racing superfans. “If you want to make any money in this sport, you need to market yourself—and he’s got a story worth telling,” says O’Shea. “He doesn’t let the good stuff go to his head, and he’s got a thick skin, so when people give him crap on Letsrun forums, he doesn’t let it bother him. That’s rare.”

Ammons says this isn’t some kind of happy accident, that years of 12-step sessions and personal therapy have enabled him to transcend the fears that used to paralyze him or nudge him into unhealthy places. “I have done a lot of work around this,” he says. “I’ve reached a place where I really don’t care what people think about me.”

In 2020, when the pandemic upended the race calendar as events were cancelled, many fast runners tapered the intensity of their training. It arguably didn’t make a ton of sense to train for races that weren’t happening. But Ammons powered through this period like little had changed. “Mitch kept doing goddamned workouts throughout the pandemic like he was training up for a race. He never pulled back,” says Morton. “Homeboy was just grinding it out, doing 100-mile weeks, like a race was around the corner.”

Ammons’s obsessive approach paid off. In October 2021, on an unseasonably warm day, he completed the Chicago Marathon in 2:23:56. A former addict who had started jogging a few years earlier finished 24th in a World Major marathon. A few months later, he ran a 1:05.28 half marathon in Houston. Suddenly all his talk about an Olympic qualifier didn’t seem so preposterous.

It is worth noting that Ammons did not feel very good when he set that PR in Houston. He had stomach pain and what felt like a fever. Ammons didn’t tell Cunningham how crappy he felt; he guessed, probably correctly, that his coach would pressure him to sit out the race. Three days later he was hospitalized for an emergency appendectomy. “So that guy goes out and runs 5 flat for 13 miles with appendicitis,” says Cunningham. “That’s the way he rolls.”

The combination of his seemingly impossible improvement and his dramatic, social-media-friendly journey brought Ammons visibility in the running community. He got invited to join and pace Jordan Hasay and other elites at a high-altitude training camp in Utah. And in the fall of 2022, he traveled to Germany to help pace Keira D’Amato as she attempted to set an American record in the Berlin Marathon.

Recounting Ammons’s journey is like journalistic Jenga—a game of stacking one improbable anecdote on a teetering tower of improbable events. You can sit back and look at it and wonder aloud how much higher it could go. How could anyone actually do that?

Ammons doesn’t know the answer. He remembers advice people gave him in the early days of a 12-step program. “They told me, ‘Just stick with it,’” he recalls. “‘In five or 10 years...you’re gonna be in a place that you never, ever believed that you could be in.’” But hearing it is one thing. Believing is another. And seeing it actually happen is yet another.

People who run, even the most talented athletes, know that you don’t have to win a race to claim victory. Maybe it’s the way that you handled adversity, or the time on the finish-line clock, or something you learned about yourself in the final minutes of effort. Since he started running seriously, Mitch Ammons has experienced this many times.

He saw that in April 2021 when he ran the Austin Half Marathon. He finished fifth. But a young woman who was working as a bike marshal shot a cool iPhone video of Ammons as he cruised across the Congress Avenue Bridge at sunrise. That woman was Jordan Whittle. They connected on Instagram later that week and eventually met for coffee. Soon they were going on dog dates—taking Mitch’s two labs (he got a puppy early on in the pandemic) and her golden retriever to the park.

Neither can pinpoint when it got serious. Whittle says her mom works at a methadone clinic in Los Angeles, so she grew up hearing stories about people struggling with substance abuse. She knows how anyone can get in over their head and she also knows how hard it is to get sober. “You can never judge somebody before you get to know them,” she says.

Friends say that Whittle has brought balance to Ammons’s life, and there’s no doubt he could use a little of that. Mitch still gets up before the sun rises, but he’s also going to a lot of social gatherings. “Jordie and their dogs are the perfect balance for him,” says Adam Waldum, a friend and training partner. “She keeps him in check and is very supportive. And she helps him with his stupid bedtimes and eating the same meal all the time.”

Ammons and Whittle got engaged in 2022. They had spent Christmas with her family and after everyone was done opening presents, he got down on one knee and surprised Jordie with a ring. They married this past May.

Ammons’s coach and teammates all have predictions of how much faster he might get. None of them know when and if and how he’ll find his limits. “He doesn’t have the sense or experiences of failure like people who’ve been running a long time have,” says Waldum. “He’s sometimes naïve to his benefit. He realizes he’s playing with house money, and he has nothing to lose.”

Ammons admits he’s at once awed, elated, and sheepish about the way strangers react to his story. He is grateful to be a symbol of inspiration, mainly because he knows what it’s like to be in desperate need of inspiration, but he’s also unsure he deserves the attention. “I don’t feel like the whole sobriety thing is all that special because I went from being a complete bum, an unproductive member of society, to just a normal person,” Ammons says. “I say this all the time—everything good in my life has come from running. And the confidence I’ve gained from running has carried over to the rest of my life.”

But those who know him best—the people who knew him when he was a kid and then an addict and now in his triumphant third act—fully understand the personal and symbolic weight of Ammons’s journey. His success is “miraculous,” says his mom, who no longer reads the obituaries on a daily basis. “He’s showing that it’s humanly possible to turn everything around. I think Mitchell feels like he got a second chance in life. And he wants to make the most of it.”

Trevor, his best childhood friend, is moved to tears at an Austin coffee shop as he tries to express what his buddy has accomplished. “Everyone is looking for a reason to wake up every day and overcome the incredibly dynamic shit that we all go through,” he says, explaining how Ammons has taught him not just the power of forgiving your friends but also the power of forgiving yourself. “Mitchell has alchemized needing a needle full of heroin into needing a 20-mile run. I feel that we all get stuck behind the identity of who we are and what we chose to do, but I think he just shows that you can pull a 180 if you want to.”

Ammons is comfortable talking plainly about his transformation and all the ways running has made his life better, but the truth is he’s still learning about it. “I have said in previous interviews that running doesn’t keep me sober, but I have since changed my mind,” he says. “I’m addicted to the miles and the workouts. I mean, I love it so much.”

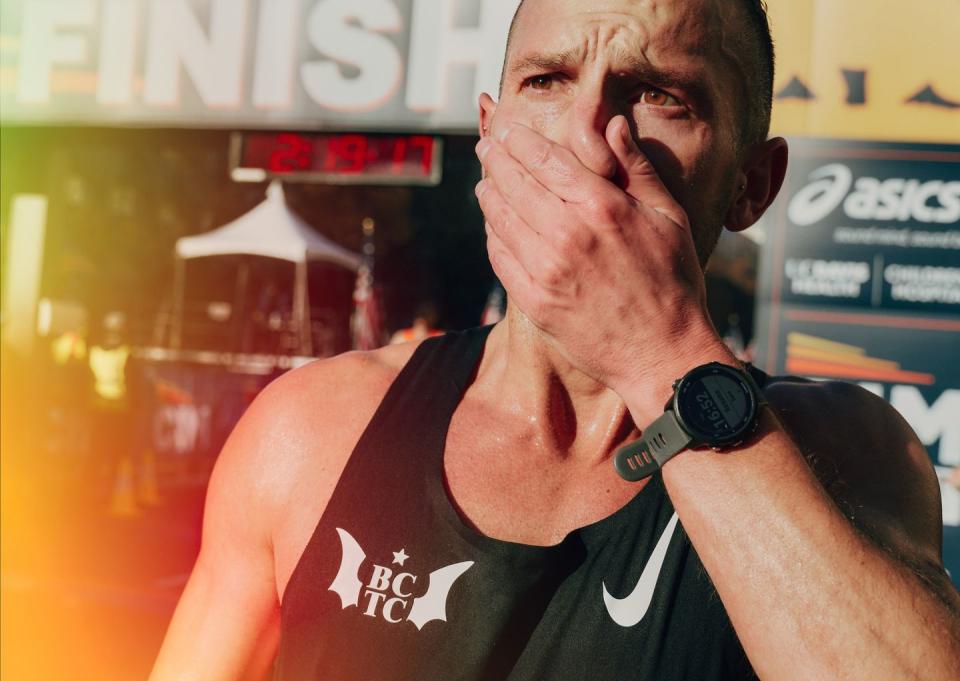

A few weeks before he and Jordie got engaged, Ammons scored another big victory without winning. He flew out to Sacramento to run the perennially fast California International Marathon. The race wasn’t perfect—he wasted a minute or so dealing with an emergency bathroom break in the second half. But his preparation and his pacing and his mental toughness were all characteristically solid, and he crossed the finish line in 2:16:48. This meant that Ammons had sliced more than seven minutes off his marathon PR—and more important, that he had qualified for the Olympic Trials with more than a minute to spare. (In October 2023, Ammons went on to shave 50 seconds off his OTQ, a personal best, at the McKirdy Micro Marathon in New York State.)

Of his performance in Sacramento, “I was really hurting for the last six miles,” Ammons recalls. “But I kept looking at my watch and I was still running under a 5:10 pace.” He worried his calves might seize up. “So I didn’t celebrate until I saw the finish line.” After he crossed it, he stood there for a minute with his hand cupped over his mouth, like he couldn’t believe what he’d just done.

Who could believe a thing like that?

You Might Also Like