How Terry Crews Became the Strongest Man in Hollywood

If you are what you eat, then Terry Crews is a mega sandwich from Fat Sal’s Deli in Los Angeles, a giant à la carte Frankenstein of everything the place offers, conceived in the most unrestrained corner of his mind. Crews goes to Fat Sal’s once or twice a week for his cheat meal. In his sandwich’s warm hoagie embrace are the following: assorted lunch meats, potato chips, bacon, a hamburger patty, and a hot dog. “You can double or triple it up,” he adds. The sandwich is fully optimized-other sandwiches measure their own limp innards against it and give up. “It’s gigantic and it’s got everything,” Crews says, placing his hands almost to the edges of the table to indicate its size.

“Oh my God. It’s like heaven,” he says.

Tonight, Crews will make do with just a burger burger. We’re sitting in “the garden” of West Hollywood’s Soho House, a members-only club. A woman in a black dress with a deep slit up the leg walks by, trailing a waddling pit-bull terrier. If the building were zoned for fowl, there would be peacocks strutting around, feeling right at home. Crews is not one of those guys who look really strong on TV but shrink in person. He seems even bigger: People spend long hours Photoshopping themselves to look this muscular. Even in a sweater and white button-down, he looks perma-flexed throughout our four-hour conversation. He orders the burger and some fries, lays out plans for dessert, and then returns to discussing his soul sandwich with the barely contained desire of a man on an Everest climb reminiscing about home.

Charismatic isn’t the right word. When he talks, his face resembles a series of stock photos of human emotion. He’s angry, then suspicious, and then wide-eyed at the wonders of the world (Fat Sal’s Deli, for example). Even when he’s describing something menial, it’s like he’s telling a ghost story. He speaks either very quietly or very loudly: “I know,” he says when I comment on it. “I have no middle.” Crews often touts his intolerance for the middle. “That character is me,” he says of the guy he played in his Old Spice ad campaign-always shirtless, always shouting. “I’m all or nothing! I live life!”

When Crews is listening, he listens with every feature. He doesn’t blink. He leans in, tilts his head, and narrows his eyes at you. He stays perfectly still until you’ve fumbled through whatever is on your mind. He doesn’t start talking after you stop talking, which makes you just . . . say more stuff. He often doesn’t seem extreme at all. He seems secure, inquisitive, restrained, friendly, and understanding. He’s the opposite of self-involved or intense.

Anyone can get Crews’s biceps, triceps, and as-yet-unnamed-ceps, but it’s this ability to stay extremely in the middle that makes him appear so strong in person.

Terry Crews would be a great celebrity interviewer.

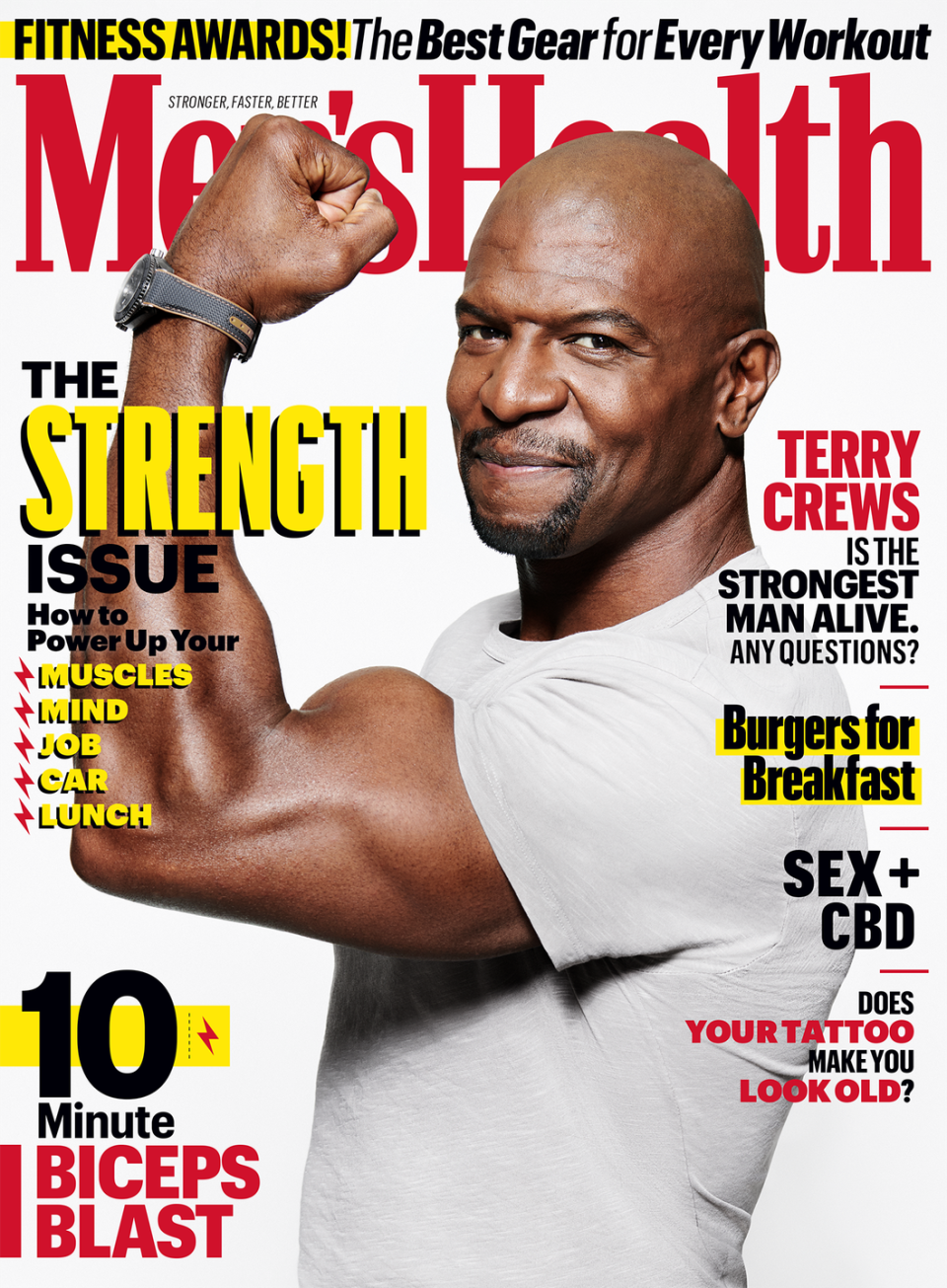

He doesn’t seem distracted at all, in spite of the day’s cyclone of activity. Crews, 50, has come directly from his Men’s Health video shoot. He spent the 20-

minute car ride to Soho House attending to his social media ahead of the finale of the latest season of America’s Got Talent, which he hosted.

Crews loves Twitter. He fires off somewhere between 10 and 900 thoughts a day. “Men have got to not only do better, but call out this behavior among ourselves as unacceptable,” he’ll tweet, or he’ll post a GIF of himself, or he’ll say, simply, “Wow,” with a link.

Social-media vigilance aside, Crews barely looks at his phone during our time at Soho House. He sets it on the table-as though to test himself-and even when it lights up he doesn’t glance at it. Crews says that growing up in a turbulent household in Flint, Michigan, with a father who beat his mother, taught him to tune out distractions better than most people. That’s certainly one reason he’s such an attentive listener.

Another reason: Crews has been unable to hear sounds in certain registers since he was a kid. Really high voices like his granddaughter’s, for instance, tend to fall out of his range. When he was 44, his doctor told him that he’d actually been relying on lip reading, without realizing it, for much of his life. “There are times where I don’t hear people,” Crews explains, “and then I just mimic the way they’re acting. They don’t know. They start laughing and I go, ‘Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah!’ I’m such a big fake. There’s a lot of mimicry, so you kind of learn to build facial expressions.”

I suddenly feel insecure, worrying that he’s just been expertly interpreting my questions through my face. “No, you’re good,” he says, not particularly convincingly.

Crews’s expressions are part of what’s made him so recognizable as an actor. So are his pecs. And abs. And lats. (Those lats!) From 1991 to 1997, Crews played football with the Los Angeles Rams, the San Diego Chargers, the Washington Redskins, and the Philadelphia Eagles. He weighs 240 pounds, and he has about 6 percent body fat. To make your strength funny, you have to be really, really strong, and Crews is. For a long time, he was “that guy,” stealing scenes in scores of films and TV shows. He was “that guy from Idiocracy” and “that really horny guy who sings ‘A Thousand Miles’ in White Chicks.” For some, he will forever be “that guy from the Old Spice ads.” These days, besides hosting America’s Got Talent, he plays a cop, also named Terry, on Brooklyn Nine-Nine.

And in 2017, after he’d built a career playing all those different guys, Crews became the #MeToo guy. He came forward to describe how he’d been groped by talent agent Adam Venit at a party in Hollywood in 2016. He was gratified by the supportive responses and unfazed by those who were convinced that he’d been paid to come forward to further the agendas of white women. “I’ve had people tell me that we had a previous relationship and it went sour,” Crews scoffs. “People have to fill in the blanks.” There was a much larger contingent that couldn’t believe Venit could have molested Crews and walked away. They wondered why Crews didn’t just hit him.

Crews used to think that being strong meant proving how strong you are all the time. He learned that growing up in Flint. “My father made sure, every time he came in the house, that we were uncomfortable. He was not happy until we were uncomfortable. That meant: Now I got respect. That’s so many men. That was me.” Then, and certainly when Crews was playing football, strength meant pushing your body to its limits, and pushing everyone around you to their limits. It meant being a great football player but, often, a terrible husband.

In the winter of 2010, right before The Expendables came out, when Crews’s career was taking off, his wife, Rebecca King-Crews, left him. He’d admitted to her that a decade earlier, he’d gotten a happy ending in a massage parlor, and for King-Crews it was the last straw. To put his family together again, he’d have to tell her about everything-even the pornography addiction that until then had been a carefully guarded secret. He’d have to study those things himself. Crews found himself alone, with nobody to impress and nobody to validate his behavior. “I didn’t have a circle,” he says. “I was literally all by myself. There was nobody to call. No group of guys I could go to: ‘Tell me I’m good.’ They would have been like, ‘She doesn’t understand you, dog. Let’s go have a drink.’ ”

Ordinarily, I’m skeptical of any man who claims to have “figured out” toxic masculinity and reformed his behavior. But Crews is not just any man. He was raised in a rigidly Christian home, for one thing, and though he now considers himself more spiritual than religious, he has a very Christian belief in one’s endless capacity for self-reinvention. He also has a superhuman ability to find motivation within: While most people have only one act, or even half an act, Crews has pulled off careers in two of the most competitive industries in America. He was desperate to change-he felt like he’d lost everything-and he had the perseverance to do it.

Hearing that the man before me is a less intense version of some raging proto-

Terry is hard to grasp. It’s like learning that a crocodile is descended from some dinosaur supercrocodile. The modern-day crocodile is still pretty intense.

The sun is going down, Crews’s burger has yet to arrive, and by my calculations, he hasn’t eaten in about 24 hours. Every morning, he wakes up before 5:00. He grabs his workout clothes, which he laid out next to his bed the night before. He takes a boatload of healthy ingestibles: multivitamins, essential fatty acids, a fat burner, enzymes for digestion, garlic, glutamine, horny goat weed. . . . He mixes amino acids into water and heads to one of several gyms he belongs to. Then he fasts until 2:00 p.m. We’d met earlier in the day at his Men’s Health video shoot, which began before 2:00, and I didn’t see him snacking at all. But Crews does not appear to suffer from the existential fussiness that most people experience when they haven’t eaten in many hours. He’s the opposite of hangry. He’s jovial and energetic-a “talker” incarnate.

“Fasting made a lot of sense, because once, I was in rehab for a pornography addiction, and they put me and my wife on a 90-day sex fast,” he says nonchalantly. Crews has turned his personal life inside out so much in the past few years that he says he no longer feels any self-consciousness. (As a woman, I find Crews’s honest answers to my questions about what it’s like to be a guy revelatory and unsettling.) “Sometimes my gauge is gone,” he says. “I remember going out with a superstar couple, my wife and I, and I was like, ‘I was addicted to porn.’ They were like-” He widens his eyes and puckers his lips.

The first time Crews and his wife attempted their sex fast, they made it only 75 days, but the next year, they tried it again and made it all 90 days. “This is the deal,” he says. “Everything that is within your grasp doesn’t need to be in your hand. You have to tell your body no. Because if you listen to your body, you’re gonna be off.”

I point out that intermittent fasting seems like exactly the kind of thing the old Terry Crews-the one obsessed with proving his strength all the time-would have done. Crews explains why it’s not: He now practices intermittent fasting because it feels good, but proto-Terry would have imposed it on other people as a way to demonstrate his control over his world. “I would require it for everyone, and that’s where the line gets crossed,” he says. “My whole family eats whatever they want.”

When we start to discuss Crews’s assault in earnest, it’s dark outside. The restaurant’s woodsy lanterns light up, and L. A.’s twinkly sprawl unfolds below. An acquaintance of his who stopped by to say hello when he arrived has dined at another table and gone.

Finding the line between doing something for yourself and doing something to intimidate or impress others has been the greatest test of Crews’s life. He didn’t vanquish Adam Venit. William Morris Endeavor, Venit, and Crews settled, and Venit retired from the agency.

“Did I get everything I was supposed to get? Did I win? Did he go to jail? No. Did he get punished by the court? By society? No.”

But Crews feels vindicated.

When he was testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee last June regarding proposed sexual-assault legislation, he described how he’d held back, even though his first instinct was to be violent.

“Why didn’t you?” Senator Dianne Feinstein interrupted. Crews looked as exasperated as you’re allowed to look when a senator asks you a stupid question. “You’re a big, powerful man. Why didn’t you-” She mimed pushing someone.

“Senator, as a black man in America-”

Crews paused for a few seconds. The idea that Crews might have Hulk-smashed Venit into oblivion without risking his acting career reflects a severe alienation from reality. (Crews is more magnanimous toward Feinstein: “Look at her era. Look where she comes from. You’re supposed to knock the guy out.”) Crews took a deep breath and looked down at the table. “Say it as it is,” Feinstein said.

Crews spoke firmly when he addressed Feinstein. “I’m from Flint, Michigan. I have seen many, many young black men who were provoked into violence-they were imprisoned or they were killed. And they’re not here. My wife, for years, prepared me. She said, ‘If you ever get goaded, if you ever get prodded-if you ever have anyone try to push you into any situation-don’t do it. Don’t be violent.’ ”

The first of those discussions had happened a decade before Adam Venit molested Crews. He and King-Crews had been standing on a busy street in Pasadena when a young man began hassling him for an autograph. The man got aggressive. Crews and his wife had just learned she was pregnant with their fifth child. The man jabbed her, and Crews snapped into action. “It was a flash of body flying everywhere,” he says. “I’m stomping this guy on the pavement.” The police arrived, and they were about to arrest Crews when a white man stepped forward from the crowd. “He says, ‘Sir, sir, stop, stop!’ He stands between me and the cops,” Crews recalls. The man explained that Crews was protecting himself and his wife. “The police believed him. They weren’t gonna believe me. I could have said the same thing. I was going to jail or getting shot. I’m a big, giant man. I look like Nino Brown [in New Jack City], stomping a man on the street. But they didn’t know the circumstances.”

It was a close call, and King-Crews wanted it to be their last. The fight occurred in 2006, post–White Chicks, when Crews was just breaking out as an actor. It was also three years after Mike Tyson was charged with assaulting two men when they taunted him at a hotel in Brooklyn. “I pulled it up on the Internet,” King-Crews remembers. “I said, ‘You

are gonna be him if you don’t quit. Our baby’s money for college is gonna go to some idiot in a bar. You have got to learn to just chill.”

Over dinner, Crews’s eyes get wet as he describes his wife’s talking-to. “Ten years later, in 2016, that incident [with Venit] would happen. I remembered my promise. This is after we built our lives together and went through all this therapy. ‘I gotta do what she wants here.’ I got in that car and I was gonna rip the steering wheel off. She just kept saying, ‘I’m proud of you, Terry.’ ” He pauses, eyes glistening. “It saved my life. I wouldn’t be here now if I’d have done it. Who would have believed me?”

After Venit groped him, Crews and his wife made their exit from the party as quickly as possible. “I wanted to break a glass and go crack the guy over the head, I was so angry,” King-Crews says. “We just held on to each other. We ran to the car and sat in the car. I just touched his arm and I said, ‘I’m proud of you.’ ”

By then the couple had survived a marital gantlet. Back in 2010, when King-Crews told him she was leaving him, Crews was self-destructing, spiraling in what he’s since described as a “cult” of toxic masculinity, and he was taking his family down with him. “I was like, ‘Wait a minute. I’m successful. I’ve got this and this. I’m living the dream.’ And she was like, ‘You can have this dream. I’d rather be broke. I’d rather be by myself.’ ” Crews let her go. “I said, ‘All right, leave. I’ll go get four more girls. I’ll be fine. Everybody thinks I’m great.’ This is how men work: We roll in a circle, and that camaraderie doesn’t allow for introspection.”

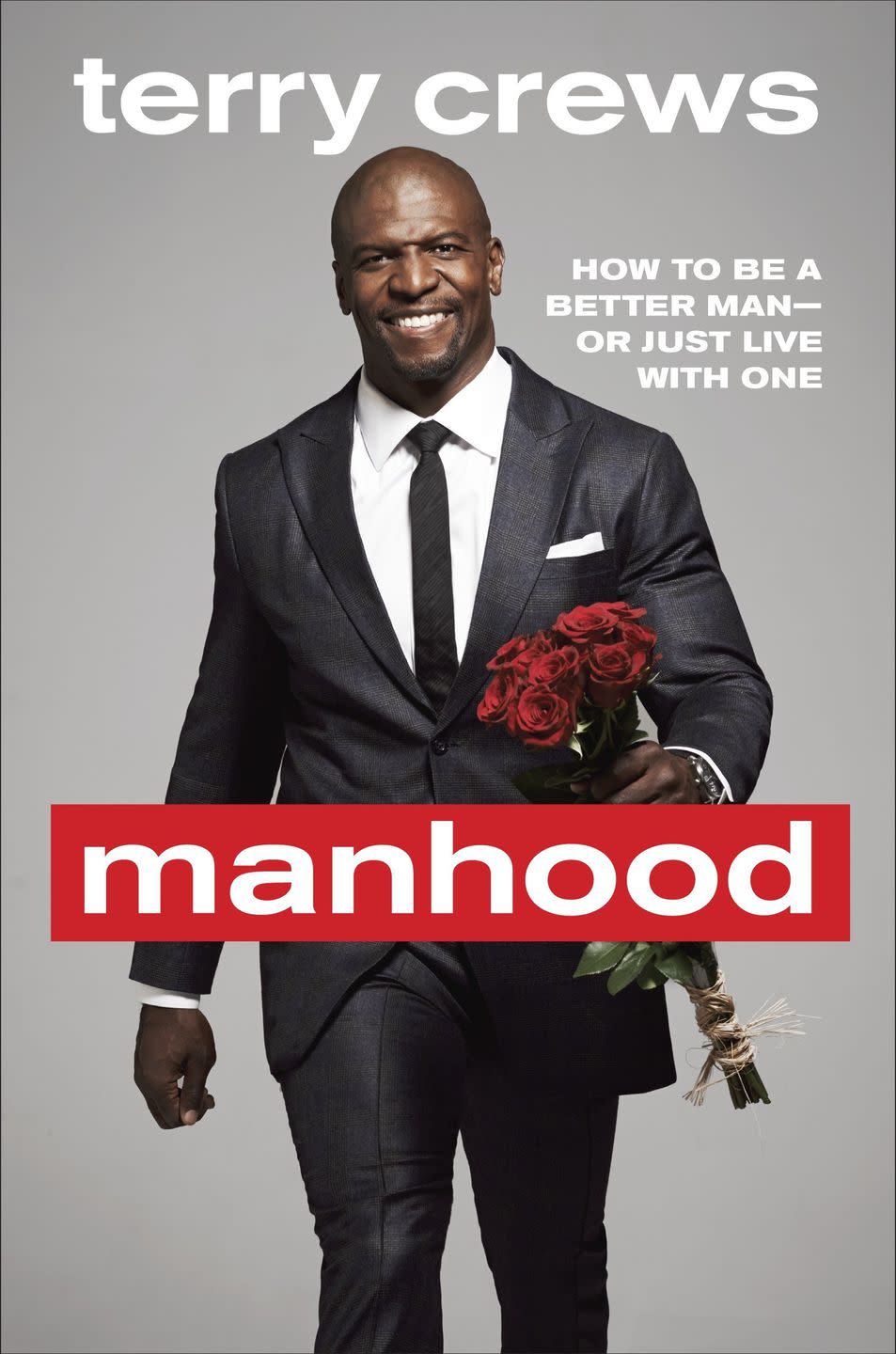

Now Crews travels around the U. S. and beyond to discuss how he broke out of that spiral of toxic masculinity. He wrote a book on the subject called Manhood: How to Be a Better Man-or Just Live with One. Crews does miss the brotherhood of toxic masculinity sometimes. “You miss buddies. You know, men bond through pain. That’s the thing I miss. I loved being on teams. I loved being in these sports. I loved, like, ‘Man, we’re doing this together.’ You know what I mean?”

I don’t, really-women establish lifelong bonds just by standing next to each other in line for a bar bathroom-but I do see the appeal of a fraternity forged in fire, and I see why one might miss it. But the Terry Crews sitting across from me also seems totally incongruous with the old Terry Crews whom he’s described: the guy who used to crave the validation of his buddies; the guy who had a pornography addiction; the guy who beat a man on a crowded street in Pasadena; the guy who would have knocked out Adam Venit.

For one thing, he’s destroying a lemon tart. He appears totally at ease with himself. Soon he’ll go home to King-Crews and won’t be awake past 10. He’ll wake up at dawn tomorrow and work out alone. “Now,” he says, “it’s about healthy Terry.”

('You Might Also Like',)