‘I was terrified that I was going to kill somebody’: how Rollerball almost broke James Caan

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Rollerball, released in the summer of 1975, was one of the wildest, most dangerous-to-make, and most immediately misunderstood films of that crazy decade. In all these ways, it was an anomaly for Norman Jewison – a headlong change of pace for the director at a mid-way point in his career.

Jewison had made his name with a sophisticated run of successes in the previous decade: two svelte Steve McQueen vehicles (The Cincinnati Kid and The Thomas Crown Affair); his sly Cold War comedy The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966); his Best-Picture-winning study of race relations in Mississippi, In the Heat of the Night (1967), containing that slap heard around the world; and the triumphant Broadway transfer Fiddler on the Roof (1971).

Rollerball was meaner, darker, and more violent than any of those: Jewison’s lone science fiction film, not to mention his bleakest social satire. The concept was a death match on roller skates, pitting teams viciously against each other on a circular track, with spiked gauntlets, exploding motorbikes and extermination as the end goal, not to mention catnip for the ratings.

The idea was cooked up by the screenwriter William Harrison, who was a literary professor at the University of Arkansas. After witnessing a brutal fight at a students’ basketball game, he wrote the 1973 short story The Rollerball Murder, which caught Jewison’s eye.

The director had already attended an ice-hockey game between Boston and Philadelphia which devolved into chaos. “There was blood on the ice and 16,000 people were standing up screaming,” he told the Guardian in 1999. A west Londoner around that time, he’d also been a regular at Stamford Bridge matches, thereby seeing the worst that 1970s football hooliganism had to offer.

Harrison and Jewison found common ground in how disturbed they were by the intersection of corporate power and violent entertainment, and saw the potential for a thriller that could serve up admonitory commentary. When Jewison offered $50,000 for the rights, Harrison bullishly upped the asking price and asked to write the script as well. Jewison agreed. They would differ mainly on how bloody the end result ought to be, with Harrison consistently wishing they’d gone much further to make it obviously repugnant, and Jewison unwilling to egg on his audience gratuitously.

It’s thought that Clint Eastwood was at one point in the running for the lead role of Jonathan E, the MVP who sticks his neck out by standing up to the shadowy agenda of his paymasters. But James Caan was an even bigger star after The Godfather, and the obvious choice, with his burly virility. “I was really persuaded to get involved by the jock in me,” admitted the late actor.

He relished the tough physical side of the shoot, but would grouse a lot about how tedious he found “all the walking and taking s___”, which was filmed in London, and is undeniably on the dull side. He struggled to remain interested in a character “whose emotions had basically been taken away from him”, and would subsequently rate the film only an 8 out of 10 for those reasons.

While construction was underway at Munich’s Olympic basketball arena on the track, which the British production designer John Box (Lawrence of Arabia) had modelled to Jewison’s specifications, Caan went to Rollerball boot camp in California for four months with the whole supporting cast, learning to skate seven days a week. There were problems when they came to Munich: that track was banked with contours 13 feet high, not flat like the one they’d trained on. “We’d just fall downhill,” Caan remembered.

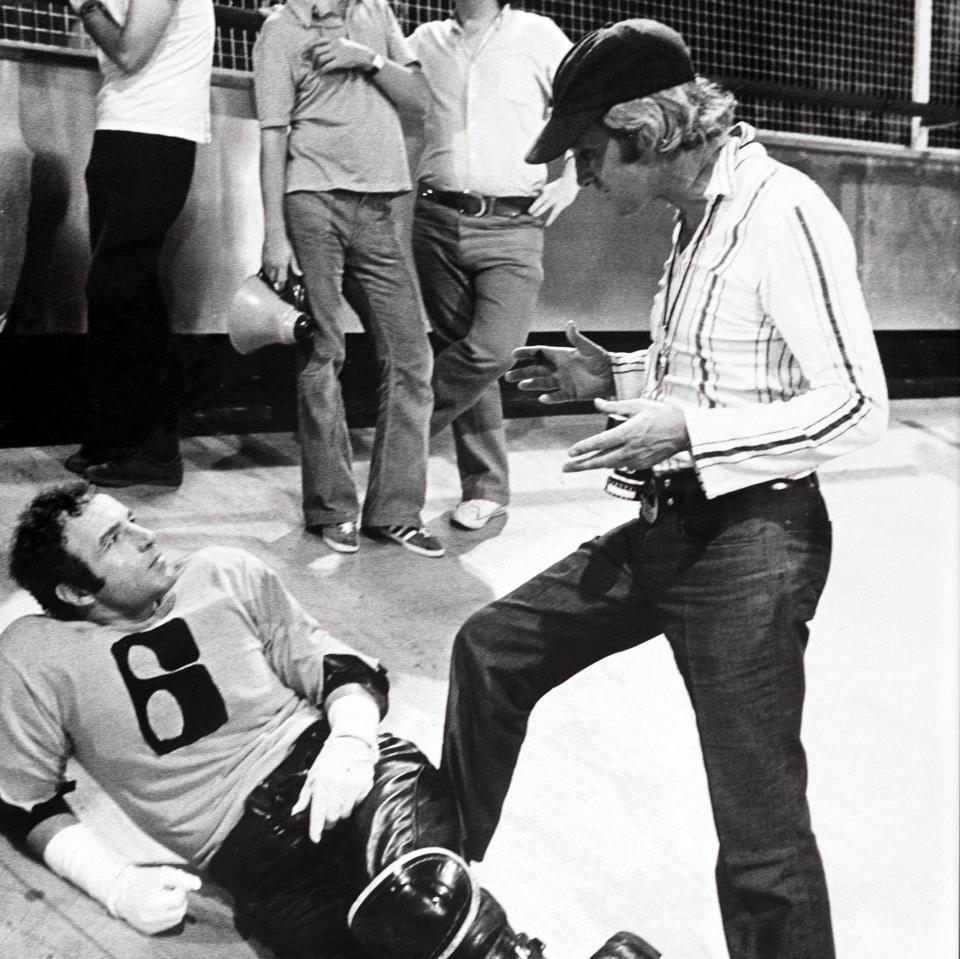

Filming these set-pieces was incredibly perilous, as Jewison would recall. “When I got into the arena and started shooting, I was just terrified that I was going to kill somebody. They would go faster and cut each other up.” Someone was laid up for six months after an injury during the training, and a stuntman was hospitalised mid-shoot. Cann separated a shoulder and damaged a rib. “But I was luckier than most,” he shrugged. The stunt performer Roy Scammell summed it all up: “Naturally, I don’t want to die, but take that out of it and it’s a terrific game. I’m sure it could catch on.”

The trouble was, it did. The film was a very solid hit, grossing $30m worldwide for United Artists from a medium $6m budget, and coming 12th in that year’s box office chart. (It was a banner year for Caan, who was also Barbra Streisand’s love interest in Funny Lady, which came in seventh with $40m.)

Although critics were unsure about the film’s tone and intent, younger audiences couldn’t get enough of it. That summer, the streets of California swarmed with teenagers re-enacting its scenes on motorbikes, spiked gloves and all. Jewison was horrified to be contacted numerous times by promoters, who wanted him to release the rights to the game so that real-life Rollerball leagues could be formed.

“I thought that violence for the entertainment of the masses was an obscene idea,” he later explained. “That’s what I saw coming and that’s why I made the film. In Europe, they bought into that idea. In America, they just wanted to play the game, man.”

The film, then, epitomises one of the ironies baked into dystopian science fiction: capture the mood of the times too well, and the prophecy you’re mounting becomes self-fulfilling. Jewison’s horror followed on from that of Stanley Kubrick, when A Clockwork Orange (1971) was accused of inspiring copycat mayhem, and Kubrick removed it from British cinemas for nearly three decades.

Flawed as it is, Jewison’s film landed in the culture with a more lasting impact than he might ever have foreseen. It proved influential on such films as The Running Man (1987) and on scads of video games in the 1980s and 1990s, including the likes of Rocketball, Killerball, Speedball and Speedball 2: Brutal Deluxe.

It was also remade, notoriously, by MGM and John McTiernan in 2002. This abysmal film was a career-killer for the director of Predator and Die Hard, and the strangest post-script imaginable. The production was so botched that it resulted, quite genuinely, in McTiernan serving a 10-month sentence in federal prison.

He was convicted for perjuring himself, after he emerged that he had been wire-tapping his own producer, Charles Roven, while the film unravelled. The FBI launched an investigation into the private investigator, Anthony Pellicano, and found McTiernan unhelpful with their enquiries. “I was just roadkill,” the director now says. None of this would have happened without Jewison’s vigilant vision of blood on the tracks – no masterpiece, and not actually as bloody as you may remember, but a zeitgeist classic in its queasy way.