Tapestries, the Original NFTs, Return for a Renaissance

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

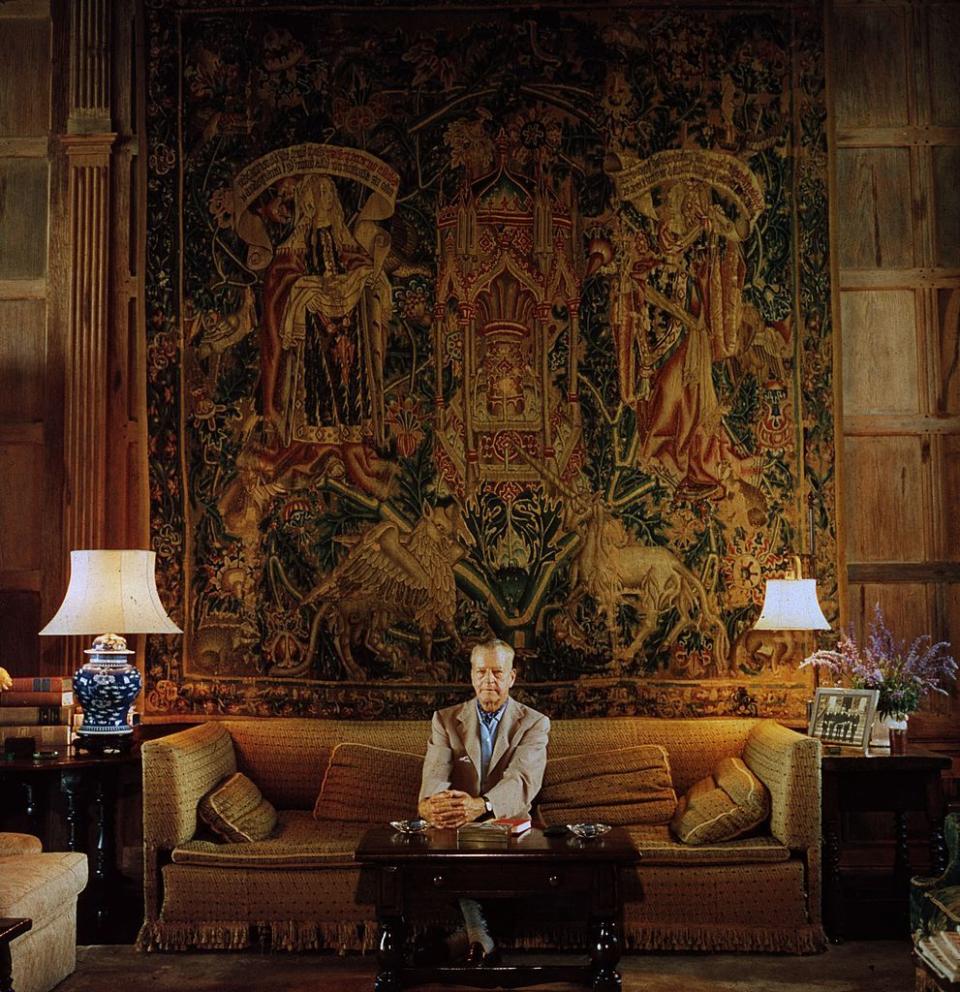

Over the course of her lifetime, Lady Helen Hamlyn, the 88-year-old widow of the late publishing magnate Paul Hamlyn, has amassed one of the world’s most impressive collections of rare textiles. Last year she decided to sell a slim selection of her hoard at Bonhams, including a mythic Flemish tapestry, of Rothschild family provenance, that was woven sometime in the early 16th century. When the gavel came down, the piece had fetched more than $330,000, roughly double the estimate.

Tapestries, it turns out, are enjoying a 21st-century renaissance. Even if the market remains decidedly niche, recent auction sales demonstrate an intense desire on the part of a competitive, upper-crust collector pool seeking a tangible distinction from the New New Money: cryptocrats and nefarious NFTers.

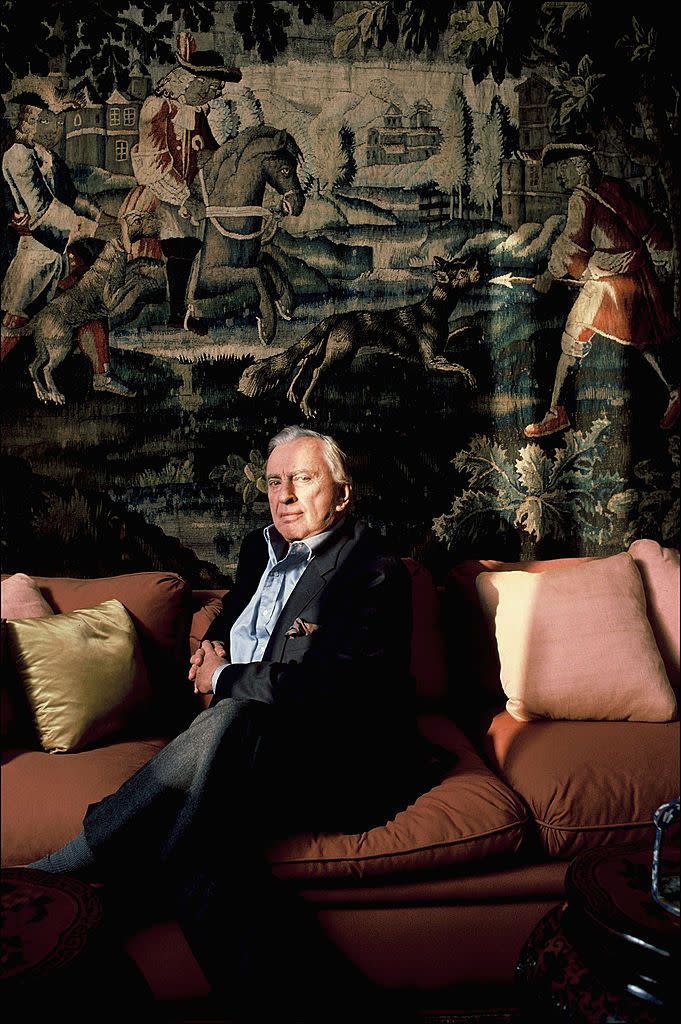

“We’re living in the mega moment,” says historian Glenn Adamson. “Not just the megarich, but mega-ambitious domestic architecture. If you’ve built a 20-foot-high, 50-foot-wide wall, how are you going to make that wall perform? Boy, a 16th-century Flemish tapestry would be hard to beat. There’s nothing more mega than a historic tapestry.”

Once used for ceremonial rituals and palace decor, tapestries were the Jeff Koonses of their time, bragging rights that telegraphed gravitas. The most prized examples were highlighted with gold and silver thread, meticulously woven in Flemish and French workshops over months or even years. “They were considered the most valuable thing other than jewelry, gold, and silver,” says Frances McCord Krongard, the European art specialist for the Washington, DC, auction house Potomack Company. “Nobles would have them rolled up and travel with them to their military camps and castles. At home they often had guards protecting them.”

In some respects such tapestries were a literal store of wealth or, as Adamson puts it, “a tremendous amount of value condensed into a single object.” In times of crisis, these tapestries were often taken apart for their materials. “The reason we’ve lost a lot of them,” he adds, “is because they were melted down for the gold and silver—which gets across just how much metal there was in them.”

By the mid–17th century, as wars depleted fortunes and dynasties fell, tapestries had lost their luster. Their fate was sealed with the arrival of the Jacquard loom in 1804.

“Tapestries went from being just about the most powerful status symbol you could have in the upper echelons of European society to, fast-forward maybe 400 years, your elderly, doddery relative might have a 19th-century French one that’s got lots of leaves, no text, no figures. The colors have faded. There are no metal threads,” says Helena Gumley-Mason, a tapestry specialist at Bonhams. “It’s a completely different animal.”

Today scarcity accounts for tapestries’ resurgence. They can no longer be crafted the way they once were, and many of the existing masterpieces are in private hands; the British royal family, which controls what may be the world’s largest private collection, has about 50 adorning the walls at Hampton Court Palace alone. Sales are few and far between, but when they take place, in-the-know modern-day Medicis (or their art advisers, anyway) champ at the bit.

And while some art collectors these days may be plonking down millions for NFTs, which are also built on a model of scarcity, a monumental Beeple collage, $69 million auction price and all, pales next to the immaculate craftsmanship of a five-century-old Flemish masterpiece.

Auction prices keep climbing, too. An early 16th-century Flemish tapestry depicting King Charles VIII on horseback went for $336,000 (four times the estimate) at Sotheby’s in May 2019, and in October 2020 a Franco-Flemish tour de force, circa 1500, sold for $930,000 at Christie’s. On the online marketplace 1stDibs, certain historic works can command nearly half a million dollars; one recent listing was $750,000.

The pandemic only turbocharged this eclectic and acquisitive cohort of collectors. “I have noticed an appetite coming back,” Gumley-Mason says. In a milieu that’s all about scale and projecting clout, a tapestry is a most elite flex. “People need to have enough space—a big wall,” says the art dealer Didier Marien, of the New York gallery Boccara. “Antique tapestries are for big houses.”

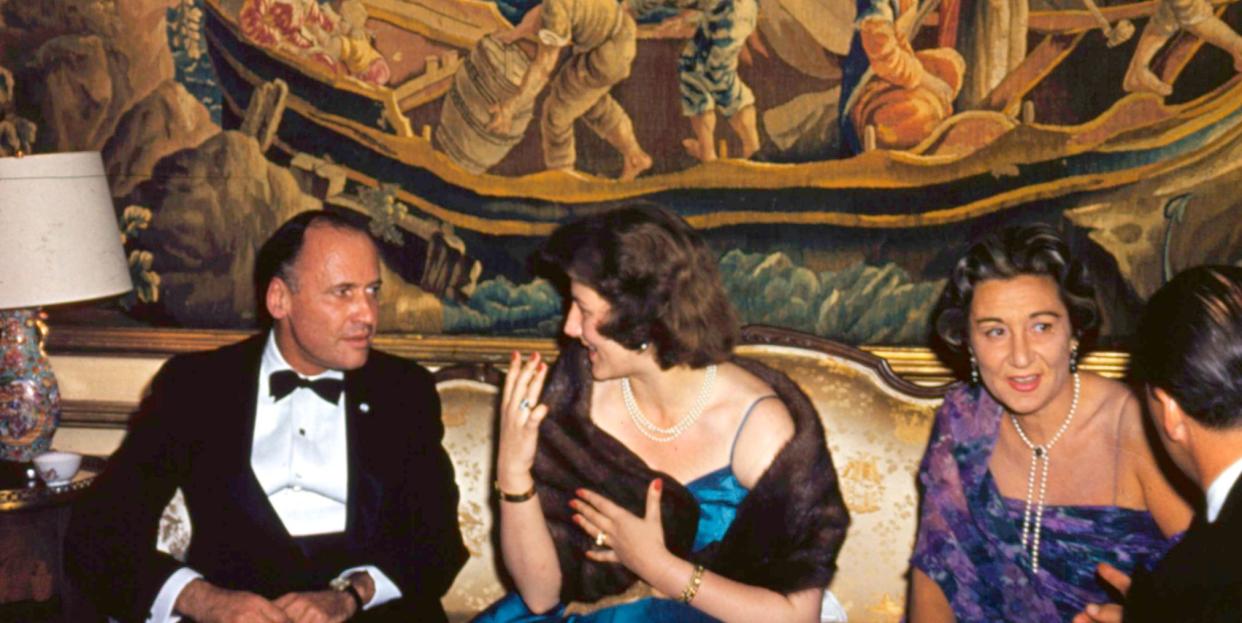

It’s not just mansion dwellers stoking the market. Modern and contemporary artists have done their part to exalt ancient techniques and bring them into the future. Alexander Calder and Joan Miró worked with weavers in Aubusson, France, and Pablo Picasso fashioned tapestries that were collected by Nelson Rockefeller. Phyllis Lambert, the heiress to the Seagram fortune, paid $50,000 in 1957 for Picasso’s 19-foot-tall stage curtain Le Tricorne, which hung at New York’s Four Seasons restaurant until 2014, when the building’s new owner, Aby Rosen, dumped it in favor of works from his private collection. (The New-York Historical Society rescued the beleaguered shroud, now valued at $1.6 million.)

During this year’s Salone del Mobile, British interior designer Ashley Hicks displayed at Nilufar Depot a series of digitally printed tapestries based on his paintings, and at Palazzo Francesco Turati the graphic design studio 75B showed a tapestry called Milano (produced by TextileLab in the Netherlands) that featured more than 130 symbolic references to the city. Contemporary African artists too are revolutionizing the medium by elevating everyday materials such as burlap, which makes tapestries more current and, in turn, coveted.

The Ghanaian master El Anatsui was the subject of a retrospective appropriately titled “Triumphant Scale” that broke attendance records in 2019 at Munich’s Haus der Kunst; in March, the winning bid at Sotheby’s for his bottle cap tapestry Wade in the Water was $1.5 million. And a younger generation continues to push the practice forward, like the 40-year-old South African Igshaan Adams, whose sprawling work Bonteheuwel/Epping, prominently featured in the 2022 Venice Biennale, channeled the “desire lines,” or footpaths crossing through segregated neighborhoods in apartheid-era Cape Town. (The phrase doubled as the title of his largest U.S. show to date, which closed in August at the Art Institute of Chicago.) Interest in Adams’s elaborate wall hangings has been slowly creeping upward since 2019, when a piece sold for $24,106 at auction; in March 2021 he set a new record, at $94,500.

Even as the meaning of the word has evolved, there’s no debate about why the tapestry as a form has kept our gaze. Its very essence is as old as man himself. In 1965 the pioneering Bauhaus fiber artist Anni Albers observed with awe that the Incas of Peru had a refined, sophisticated textile culture even before they developed written language, and that was before the conquistadors invaded.

“Along with cave paintings,” she wrote, “threads were among the earliest transmitters of meaning.” Strung together, they form a catenary that stretches from the earliest Andean weavings to what Le Corbusier came to call “the mural of the modern age,” connecting us all in the long arc of history.

This story appears in the September 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like