What It Takes to Stay Warm on Cold-Water Swims

This article originally appeared on Outside

To have your swim across the English Channel officially recorded by the Channel Swimming Association, you have to jump through a number of hoops long before the actual 21-mile crossing: passing a medical exam, picking a date with appropriate tides, booking a boat pilot to accompany you. Pilots on the official list are currently taking reservations three years out. You also need to complete a verified six-hour swim in water temperatures of 60 degrees Fahrenheit or less--which, as it happens, is right around the recommended temperature range for post-exercise ice baths.

In a recent issue of the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, French researchers tested swimmers at a Channel Swim Camp in Brittany, where attendees were attempting to tick off their six-hour swims. Unfortunately for the swimmers, water temperatures were around 55 degrees Fahrenheit. A total of 14 swimmers agreed to swallow ingestible thermometers to measure their core temperature during and after the swim, offering some sobering insights into what happens during--and, of particular interest to the scientists, after--prolonged cold-water swims.

The group included 11 men and 3 women, with an average age of 38. Their average weight was 190 pounds, corresponding to a BMI of 26.1 and body fat percentage of 19.2. (We'll come back to why that matters.) All of the subjects were experienced swimmers doing regular open-water training, but only eight of them reported getting cold exposure on a weekly basis in the form of cold showers, cold-water immersion, or cold-water swimming.

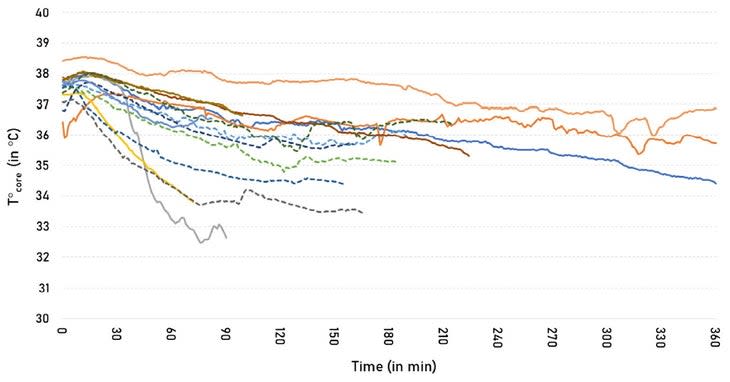

So how did the swims go? This is one of those cases where a picture tells the story pretty effectively. The following graph shows core temperature, in Celsius, for each of the participants during the swim. Some relevant thresholds: normal core temperature is around 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit); hypothermia is considered to set in below 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit).

The first thing to notice is that only three of the lines make it to the target of 360 minutes. The rest of the swimmers dropped out early. The average duration was just 194 minutes. And it's not hard to see why they dropped out: the faster the decline in core temperature, the quicker they dropped out. The limiting factor was clearly hypothermia, with seven of the participants dipping below 95 degrees Fahrenheit during the swim.

A relevant comparison: in a similar study from 2016, all nine of the swimmers successfully completed the six-hour swim in 60-degree water. Only one of the subjects developed hypothermia. This is why World Aquatics, the sport's governing body, has a minimum temperature of 16 degrees Celsius (60.8 degrees Fahrenheit) for open-water marathon swimming, with wetsuits compulsory below 18 degrees Celsius (64.4 degrees Fahrenheit).

On the topic of wetsuits, just six of the swimmers in the new study wore wetsuits. It didn't turn out to be a crucial factor: the three successful swimmers all swam in regular swimsuits. That doesn't mean that wetsuits are totally useless; it just reflects the fact that the swimmers who wore wetsuits were, for the most part, the thinnest. Instead, the biggest factor appeared to be the layer of insulating fat.

If you look back at the graph, there's one line that stands out from--and above--the rest. This swimmer started with a core temperature of about 101 degrees Fahrenheit, and after six hours was at a perfectly normal temperature of around 98.5 degrees Fahrenheit. This participant also happened to have the highest body-fat percentage, at 26.9 percent. That certainly helps, but it's not the whole story. They were also the most experienced cold-water ultra-distance swimmer in the group. The elevated starting temperature might be explained by some gentle pre-swim exercise, which is a common practice. But there are also several reports (most famously of polar swimmer Lewis Pugh) that experienced cold-water devotees develop a conditioned Pavlovian response in which the prospect of a cold-water swim prompts their core temperature to rise before they even dive in.

There's a postscript to the swim. In fact, investigating it was the main purpose of the study. When you get out of the water, your core temperature continues to drop for a little while. This can be dangerous, as swimmers (or rescued accident victims) who seem OK can drop into hypothermia after they're seemingly safe. There are likely a few different mechanisms that contribute to this prolonged cooling. For one thing, once you stop swimming you're no longer generating metabolic heat. As you begin rewarming, blood returns to your frigid extremities, gets chilled, then recirculates to your core. And there's direct conduction of heat from your warm core to the cold outer tissues--which means that a thick layer of fat, so useful for keeping you warm during the swim, can be a disadvantage after the swim because it draws more heat from the core as it rewarms.

Sure enough, the swimmers' core temperature kept dropping for an average of 25 minutes after they exited the water, going from 95.4 degrees Celsius to 94.4 degrees Celsius and crossing the threshold of hypothermia. And those with the highest BMI and body fat percentage cooled the most. The champion, with a post-swim cooling period of 66 minutes, was the swimmer who had the unusually elevated core temperature throughout the swim.

The fact that wetsuits didn't magically permit the thinnest swimmers to withstand the cold water is, perhaps, a little disappointing. Staying warm during long open-water swims has long been a vexing challenge. When I was researching my book Endure, I came across the story of the pioneering open-water swimmer Jabez Wolffe, who in the early 1900s made 22 unsuccessful attempts to swim across the Channel. In one, he had to be pulled from the water a quarter-mile from the finish "despite being slathered head-to-toe with whiskey and turpentine and having olive oil rubbed on his head." Even these days, the Channel Swimming Association warns, "Channel Swimmer's Grease" is very difficult to obtain: "you should experiment to find out what is most suitable for you and be prepared to make up your own blend." And if all else fails, perhaps consider an extra helping of dessert.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.