Sympathy Isn't Good Enough. Ava DuVernay Wants 'When They See Us' to Inspire Change.

It’s reasonable to wonder, amid our degrading civic discourse, whether Twitter is anything more than a toxic pool full of trolls. If you follow Ava DuVernay, who is as fearless in 280 characters as she is in person, it’s also reasonable to believe the social media platform can be a catalyst for positive change. The 46-year-old filmmaker has tweeted 40,000 times to—as she does in her films—decry injustice, amplify the voices of underrepresented members of society, and incite activism.

In using her voice to raise awareness and funds for issues dear to her, she has also raised her profile, amassing more than 2 million followers, likely the most of any female or African-American director. DuVernay has another reason to believe in Twitter’s power to connect: her devastatingly powerful new project, the Netflix limited series When They See Us, which was born out of an unexpected tweet.

Four years ago, tucked amid the likes and attagirls in her feed, DuVernay found a tweet directed at her that read: what’s your next film gonna be on? #thecentralparkfive #cp5 #centralpark5 maybe???? #wishfulthinking #fingerscrossed. The Hail Mary–like missive came from Raymond Santana Jr., who had been one of the five New York City teens falsely accused in 1989 and convicted in the Central Park Jogger case.

DuVernay knew the story, perhaps the most widely publicized and racially charged case of the 1980s: black and Latino teens from Harlem strong-armed by the police into giving false confessions, found guilty despite major inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case and a lack of any physical evidence or witnesses, and demonized in media coverage that made the case a national story. She messaged Santana to suggest they meet for dinner. As she says with a sly chuckle, “I slipped into his DMs.”

“Once I got to the restaurant, I talked to her like to the brothers,” Santana says, referring to the other members of the so-called Central Park Five. DuVernay then met them one by one: Yusef Salaam, Kevin Richardson, Korey Wise, and Antron McCray. As a teen DuVernay had been captivated by their case. Growing up in the Compton neighborhood of Los Angeles, she was acutely aware of racial bias; she remembers heavily armed cops swarming into her back yard and tackling her father while he watered the lawn, as they ostensibly searched for a fugitive.

And yet despite her many accomplishments, when it came to telling this story, DuVernay says, “it wasn’t just like I chose them. They had to decide if I was the right person.”

Santana had no doubts. He reached out after seeing Selma, DuVernay’s drama about the 1965 march for voting rights, the first film directed by an African-American woman ever nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. “It showed me that she wasn’t afraid to tell the truth and she took her craft very seriously,” Santana recalls. “I said, ‘This is the person we need.’” DuVernay brought many other bona fides to the table—including the then-in-progress 13th, her 2016 documentary about systemic racism in the criminal justice system from slavery to the present day. Neither Santana nor the other members of the Five knew that their case figured prominently in the film.

DuVernay changed the title of the four-part Netflix series from Central Park Five to When They See Us, because it is, she says, also about millions of young people of color who are blamed, judged, accused on sight. “Often when you hear ‘criminal,’ they’re dehumanized,” she says. “What we try to do in the series is show that these are living, breathing people with thoughts, memories, feelings, families.”

“No one got an opportunity to really investigate who we are,” Salaam says. “It was easy for the system to become what I call the spiked wheels of justice and just mow us down.” McCray says, “The things they did to me in the interrogation room… They did terrible things. I lost my religion; I stopped believing in God. I thought, How could the police get up on the stand, put their hands on the Bible, and lie? I knew the truth would come out someday. I just thought I wouldn’t be alive to see it.”

Thirty years after the arrests, When They See Us illustrates how much and how little has changed. Inherent bias. Police misconduct. Prosecutorial overreach. Politicians whose demands for justice reverberate as racist dog whistles. It’s telling that spotlight-grabbing public figures from that time have since gained in prominence. Consider the full-page ad in the major newspapers that called for the death penalty for the Five (who were just 14 to 16 years old when they were arrested) taken out by a real estate tycoon who would later ride race-baiting rhetoric to the White House.

The story of a group of black and Latino boys raping and beating a white woman investment banker into a coma stoked the city’s simmering racial tensions. “It was a type of blood lust—an angry mob. The assumption of guilt happened almost instantaneously,” says Natalie Byfield, a reporter covering the case for the New York Daily News and author of Savage Portrayals: Race, Media and the Central Park Jogger Story. Her research found that fewer than 5 percent of the stories in the aftermath of the jogger’s attack used the term “alleged” in reference to the Five’s purported role.

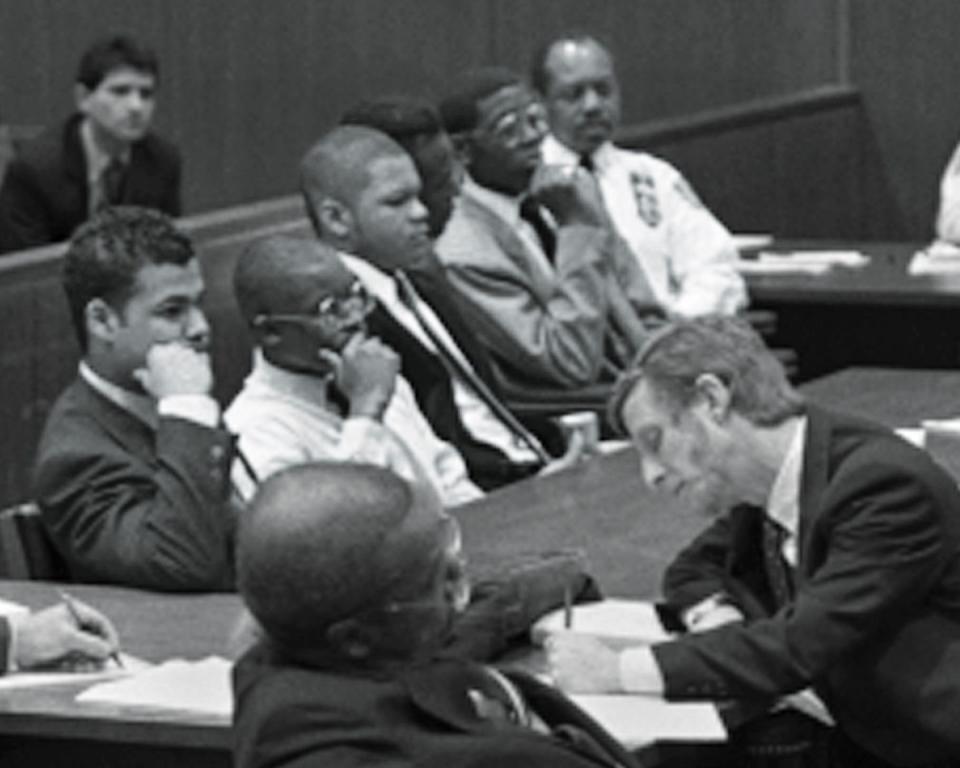

The Five, who were picked up as part of a large group of teenagers engaging in various degrees of mischief in Central Park that night, were labeled “a wolfpack” and “super-predators” and called far worse by the crowds at their trials. “As you walked into the courtroom, people were screaming and jeering. It was just terrifying,” recalls lawyer Barry Scheck, co-founder of the Innocence Project, who advised one of the defense attorneys in 1990 and served as a legal liaison in the reinvestigation that led to the convictions being vacated in 2002. “I was deeply troubled by the whole case,” Scheck says. “The evidence had a lot of problems and contradictions.”

When a convicted murderer and rapist named Matias Reyes later confessed to the attack, and DNA evidence confirmed that he had been the lone rapist, “it didn’t surprise us at all,” Scheck says. “I’d like to believe it’s less likely and there is less of an excuse for it happening again,” he adds. “But of course this can happen again.”

“All of them were picked up off the street that day for just being boys—boys will be boys,” DuVernay says. “Just like Brett Kavanaugh, just like all the white boys or the women reading this magazine who go on spring break and do all kinds of things and are never considered a wolfpack or a gang, never given the full brunt of the criminal justice system. The hope is that people can watch this story and consider the evils of that system. The film is designed to inspire conversation and change.”

By the time the Five were exonerated—despite opposition by the police and prosecutors involved in the case—they had already served their full sentences. Together they filed a civil suit against New York City for malicious prosecution, racial discrimination, and emotional distress. Finally, in 2014, they received a $41 million settlement, though the city did not admit to any wrongdoing. “I don’t feel vindicated, no,” Richardson says. “There’s no amount of money that will equal what we endured in prison. We have these scars that nobody sees.”

“I cried and cried when I found out,” McCray says of learning about his exoneration. “I cried for what I’d lost. My father died never knowing that the truth came out.”

“Korey said, ‘This is life after death,’” Salaam says. Wise, who was 16 when arrested, was convicted as an adult and served nearly 14 years at various prisons in New York state. DuVernay decided to devote the series’s final episode to his experience. “One of the things that really struck me was when Korey said to me, ‘There is no Central Park Five. It was four plus one. And no one has told that story,’ ” she says. “I think it’s important for people to understand the depths of what it means to be incarcerated in adult prisons in this country.”

The victim of horrific beatings, Wise carries with him trauma that the others acknowledge is on a different level. “I’m just a shadow,” he says. “I’m very empty—46 years old and empty. At the same time, I’m talking to the kid in me: ‘I got you, baby boy. Nobody can take your story from you.’” Seeing that story onscreen was surreal for the four assembled members of the Five (McCray, whose mother had just died, was in Atlanta).

“At the end,” DuVernay says, “getting their blessing and approval was one of my biggest career achievements. And I’ve had some pretty good ones.” She says she generally refuses to cry at her own work, “yet when I got to the end of episode four, I cried like a baby. The cumulative emotion broke me down in a way that was unlike anything I’ve done,” she says.

“It was just profoundly moving for me, personally, that these men allowed me to tell their story, and deeply resonant for me as a citizen of this country that this is something we allowed to happen. And it’s not just happening to them, it’s happening to so many people.”

Photo at top: Tiffany & Co. earrings ($2,800); trench coat, her own. Hair by Dr. Kari Williams for Ava DuVernay at Mahogany Hair Revolution. Makeup by Ernesto Casillas for Nars at the Only Agency. Production services provided by Viewfinders.

Photograph by Gillian Laub; Styled by Jason Bolden

This story appears in the Summer 2019 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like