Swimply, and the Public/Private Pool Divide

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Pool access has been a surprising linchpin of some of America’s most significant cultural moments. What does it mean that you can now rent your neighbor’s watery paradise?

It was September 2022 and Lexi Pandell, a 33-year-old East Bay native living in nearby Danville, California, was trying to figure out if she should have a bachelorette party. The state was experiencing a heat wave—"the hottest and longest on record" for the month of September, the governor noted. All across the West, more than a thousand heat records were broken. There was only one idea that made any kind of sense: a pool.

"I am in a part of town that’s a lot of ranch-style homes and rentals," Pandell says. There is no pool at her place or at any of her friends’; none of them live on "the other side of town [where] it’s these mega mansions with giant pools and giant back-yards." As the world gets hotter, we are becoming a country increasingly obsessed with private pools—there are more than 10 million in the U.S.—but only 8 percent of American households have a residential pool, according to research by the Pool and Hot Tub Alliance.

Pandell wasn’t concerned about having a bachelorette party at all, but her friends offered to plan it. She insisted on something low-key: a private, intimate setting where a group of millennial women could drink, get Mexican food delivered, and listen to Beyoncé in peace. Basically, she wanted to simulate the experience of owning a pool without actually owning a pool.

Thankfully, there’s an app for that: Swimply, a marketplace that allows users to rent pools owned by their more fortunate neighbors. The service, which takes a 15 percent cut from hosts (who set their hourly rate) and 10 percent from guests, now lists about 25,000 pools in 125 markets in the U.S., Canada, and Australia.

Pandell’s friends had heard good things about what’s commonly referred to as the "Airbnb for pools." Given the small size of their town, when they opened the app they didn’t have to search long. For just $80 an hour, they’d get to float in a saltwater oasis, plus so much more: There were rocks to jump off, plus a slide, a waterfall, a hot tub, and more lounge furniture than they could possibly use. The outdoor area also included a massive kitchen with a bar and a grill, speakers, and a TV, as well as private bath/shower access and free Wi-Fi. The reviews were all glowing.

"I am extremely jealous of all the people here who do have pools. So I was like, Well, I can kind of live the fantasy for a second," Pandell says. "There is something really intriguing about getting a dip into the other side and, on the other hand, kind of depressing too. I live only a few miles from you, but what a different existence I have."

In the West, we dream of water. California is home to some 1.3 million private pools. The indoor-outdoor lifestyle dream traces back a century, to when the rich and famous zeroed in on the pool as one of the most aspirational features of a California home.

Starting in the late 1920s, architects like Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra began designing homes for their Californian clients with pools as integral architectural features, not just rectangles out back filled with water. Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford were said to have built the first in-ground pool in the L.A. area at their Beverly Hills estate; the couple were famously photographed canoeing in the pool, which was 100 feet long. It wasn’t until the middle of the century, when a California-based company refined gunite, essentially sprayable concrete, that private pools became much more affordable.

But long before the private pool became the object of lust of every upwardly mobile American household, public pools were symbols of our country’s commitment to exclusion. In the early 1900s, pools were segregated by gender, but their eventual integration meant the intimate public spaces became hotbeds of fear over miscegenation. In the 1920s and ’30s, though thousands of public swimming pools were opened across the country—what is known as the "swimming pool age"—virtually all were segregated racially, either by law or by acts of violence.

According to Jeff Wiltse, author of Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America, some historians say the modern civil rights movement kicked off in Southern California over the right to swim at public pools. In 1914, Pasadena opened the Brookside Plunge for whites only. Protests from Black citizens brought a concession: People of color could come one day a week, right before the pool was cleaned. Further protests led to a complete ban until 1929, when the once-weekly day—dubbed "International Day"—was reinstated. The pool wouldn’t desegregate until 1947—only to shut down a year later. It was the racial integration of pools across the country that led to mass shutdowns, and the wealthy flocked to new private (and segregated) swim clubs or took aim at getting ones of their own.

The desire for a pool of one’s own would be emphasized for Californians, who, even before we recognized that the effects of climate change exacerbated matters, were plagued by drought and punishing heatwaves. To us, the pool is a kind of oasis, our collective thirst intensified by a cultural obsession with glamour and leisure. "A pool is misapprehended as a trapping of affluence, real or pretended, and of a kind of hedonistic attention to the body. Actually a pool is, for many of us in the West, a symbol not of affluence but of order, of control over the uncontrollable," wrote Joan Didion in 1979, two years after the state experienced its driest year in history up to that point. "Water is important to people who do not have it, and the same is true of control."

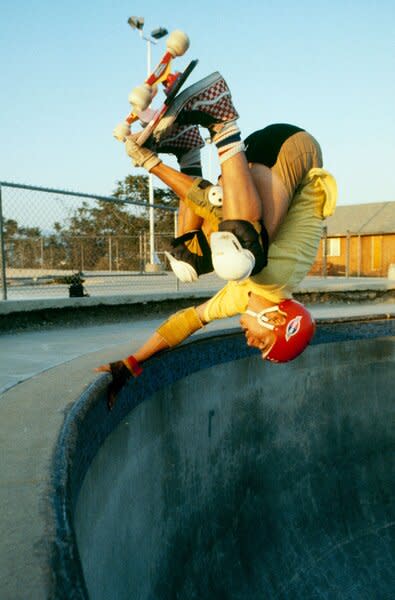

The punishing drought of the mid-1970s was one of many times that nature has intervened to pull back the veneer of the Californian dream. We owe the popularity of the phrase "If it’s yellow, let it mellow; if it’s brown, flush it down" to this period. Exuberant green lawns across the state were drained of all life (and color) as families were instructed to turn off their sprinklers. In some places, couples would shower in pairs and collect water in a bucket to use later for flushing toilets or laundry. And, of course, people drained their pools. Environmentalism, coupled with a wave of foreclosures, meant pool draining hit hard in Southern California, where the majority of the state’s gorgeous money pits are located. Perfectly paved kidney beans filled with aquamarine H₂O became unattended wastelands that (to some) were ripe with opportunity.

The western impulse is to create something out of nothing, and it can’t be dissuaded by concepts like private property. Pioneering skateboarders like Tony Alva, Steve Olson, and Stacy Peralta realized that these empty pools would be perfect for their burgeoning sport. They’d search fancy neighborhoods for the nicest ones and then, when people were at work, hop their fences and do half pipes all day.

"L.A. was the backyard pool mecca. But not just the backyard pool mecca, the properly, beautifully designed backyard pool. I don’t know of any place in the world that has that proliferation of that kind of voluptuous, sensuous design," Peralta said on the podcast 99 Percent Invisible in 2017. "We fell in love with the shapes."

Though many days would end with angry homeowners chasing the boys off, for those brief moments the skaters got access to a world previously off-limits. The lack of water was essential, and when the skaters encountered pools that were still wet, they drained them. "We were a bunch of scruffy kids and here we are riding in backyard pools and we know what we’re doing is beautiful," Peralta said. "And we get to feel beautiful."

See the full story on Dwell.com: Swimply, and the Public/Private Pool Divide

Related stories: