Sustainable Ways to Achieve Y2K-Inspired Dirty Washes

The denim industry has made strides in cleaning up its wasteful ways, but one fashion trend is dragging it back to its dirtier past.

Whether you call it “vintage tint” like New Jersey-based BPD Washhouse, “dirty look” like Italian chemical company Officina39, or “dirty, smokey or trashed” like Turkey’s Isko, it’s safe to say that gritty, apocalyptic washes are back.

More from Sourcing Journal

Blackhorse Lane Gives UK Designers a Domestic Solution for Denim R&D

Color and Creativity Take Center Stage at Kingpins Amsterdam

Monforts Touts Flexibility of All-In-One Continuous Dyeing and Finishing System

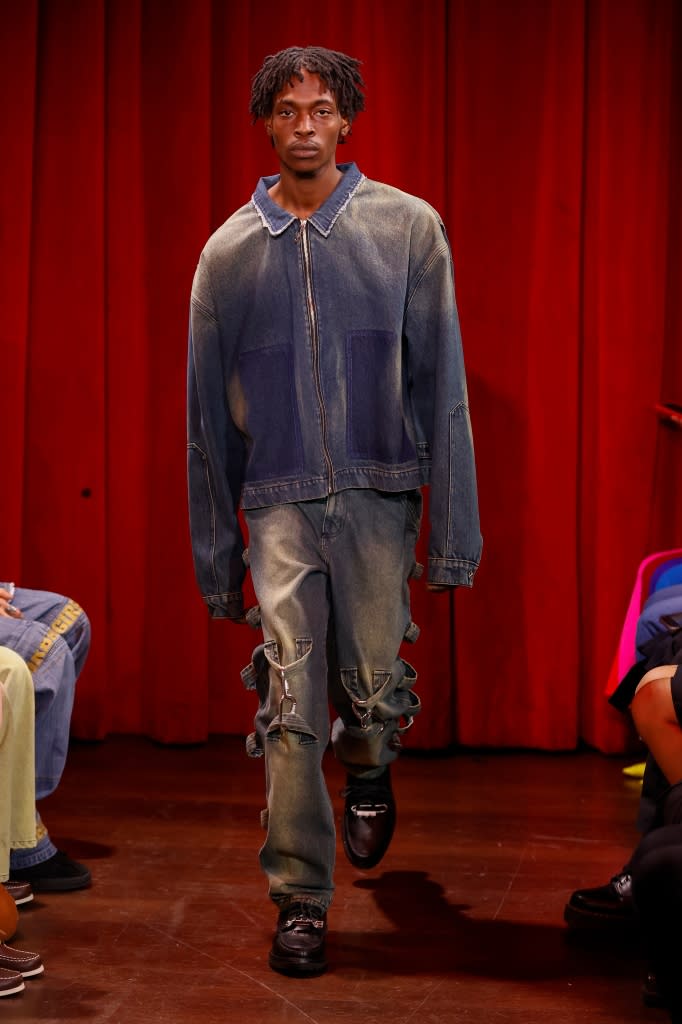

Blumarine, R13, Foo and Foo, Acne Studios and Diesel are among the brands to inject dirty-looking denim into their recent collections. Defined by its earthy tint, vintage fades and dull appearance, the edgy look fits in with Gen Z-oriented trends from Y2K and grunge to moto. The wash is at home on items that haven’t been popular in nearly 20 years, including low-slung jeans and midriff-baring miniskirts.

“These types of washes were extremely in vogue in the 2000s, especially with Italian brands such as Diesel,” said Alice Tonello, R&D and marketing manager for Italian machinery company Tonello.

She said Diesel developed two models with this type of wash, the 736 with a reddish look, which was dirtied using wall dyes, such as ferrous oxide, and the 738, a second style with an intense orange color. “Later [Diesel] switched to using mineral pigments, and later, even to this day, colored mineral pigments to achieve the same effect,” Tonello said. “This wash made the fortune of brands such as Diesel.”

Though trendy, Paolo Gnutti, CEO of PG and the creative director of Isko Luxury by PG, likens the existence of dirty denim to the first appearance of chino pants in the mid 1800s when an English army officer in India was trying to hide in the dust. To dye the chinos, the officer mixed spices and coffee to create shades that went from sand to ochre, according to Gnutti.

Similarly, the first industrial dirty effect in the 2000s involved the use of natural pumice stones from mountainous Greek or Turkish quarries and dye pigments. “This kind of technique, unfortunately, had a high environmental impact on residual sludge and chemicals that are difficult to remove and dispose,” he said.

Several methods were used to achieve the dirty look at the height of their popularity in the early 2000s.

“The traditional way that brands achieved the look back in the 2000s was by exhaustion, adding direct dyestuffs together with salt, increasing the temperature of the water up to 50-60ºC, and running the machine for 10-15 minutes,” said Amor Cardona, member of Jeanologia’s BrainBox team. “After this time, bath water with remaining dyestuff and salt was drained. Then, rinses were done to eliminate the chemical products remaining on garments.”

Other times the garments were sanded by hand and then treated with pumice stone to get the stone effect. Chlorine and permanganate were used for bleaching and localized corrosion. Finally, pigments or reactive dyes were used for over-dyeing or even double-dye processes.

What they all have in common, according to Ivan Manzaneda, Isko’s R&D lead, is their environmental impact, “starting from the huge amount of water consumption to finish one garment, to the hazardous chemicals or the total number of compounds needed in the whole process.”

“In general, these industrial processes were characterized by the use of products that were chemically hazardous to the environment or that were difficult to dispose of,” Venier said.

The human impact of these techniques is not to be overlooked. The high number of steps, risky chemical applications and manual operations puts workers in danger. Potassium permanganate and sanding processes result in “considerable harm” to the workers who handle it, he said. Meanwhile, poor management of toxic substances poses a risk of water pollution, potentially affecting many more people and aquatic life.

“Denim manufacturers are increasingly moving toward sustainability,” Gnutti added. “However, the fact remains that in terms of washing, there are still some limitations in the look of a 100 percent sustainable wash. There’s a long road ahead, but it is the right one and the denim sector is constantly working to improve it day by day, season by season.”

Sustainable alternatives

Dirty denim is shedding its reputation, however. Brands can replace many traditional processes by eliminating stones, certain chemicals and local applications, and reducing the total water to finish a garment. Some manual applications and steps are also reducing the impact on workers.

Gnutti said innovation in the last decade has revolutionized the market by almost completely replacing natural pumice stone with various types of synthetic stones made of rubber or recycled plastic. Depending on the weight and type of fabric, he said alternative materials can fully replace natural stone in terms of the final look.

“Today this type of effect can be done more responsibly by using direct dyes or colored mineral pigments directly in the bath. It is done at lower temperatures and is very short, 5-10 minutes maximum,” Tonello said.

Brands can also achieve the look through atomization with Tonello’s Core system, a misting finishing process garment that allows maximum dye optimization and significant water savings. “This automatic system, operated entirely by the machine, can produce a fine mist inside the washing machine drum, resulting in uniform or contrasting effects on the garments,” she said.

Jeanologia’s eFlow technology, which uses nanobubbles of air instead of using water as a transport of the dyestuffs to the garments, is another way to apply dyestuff. The technology uses minimal quantity of water, product and energy with zero discharge, achieving savings 95 percent of water, 90 percent of chemicals and 40 percent of energy.

“With eFlow no residue is obtained, neither of contaminated water nor of chemicals, obtaining the same result as with tinted or dirty by exhaustion but in an environmentally friendly and efficient way, saving costs to the industry,” Cardona said.

Manzaneda said sustainable finishing technologies like nebulization systems, ozone and laser combined with chemical compounds that are Bluesign and ZDHC approved and a knowledgeable team can provide different options and solutions.

Isko’s mineral dyes are one option, he added. “They are created with natural dyestuffs—not oil-based or synthetics—coming right from the earth.” In addition, by working with suppliers that have a recycling water system like Isko’s Creative Room Hub in London, Manzaneda said they can develop 100 percent of their garments using recycled water, reducing the waste in the development stage.

Soko’s Easy Wave dyeing method is another solution, according to Matteo Urbini, managing director of the Italian chemical company. “Pigments and resins previously used were more complicated to get treated,” he said.

Easy Wave is a dyeing auxiliary that creates a look like cold pigment dyeing without using any pigments and without the inconvenience of using pigments. The look is a surface dyeing with lighter seams, a good hand feel and good fastness.

Officina39’s goal is to match the dirty vintage looks of the 2000s with ethical, honest, transparent, and socially responsible alternatives.

The company utilizes Aqualess Mission, its combination of technologies allowing garment laundry processes to use 75 percent less water. Aqualess Aged is used in combination with Aqualess Activator to create the stone effect and replace the pumice stone treatment. Oz-One Powder and Ind/J Remover are applied locally to replace the use of potassium permanganate and chlorine on denim and obtain a bleached and distressed vintage look in an eco-friendly way.

Officina39’s One Step Process can combine several of these processes at the same time, saving time, energy, space and water. “That means that a raw garment enters the machine and a garment with a basic vintage effect comes out ready to be dried, already treated, bleached and softened,” Venier said.

For over-dyeing Officina39 uses Recycrom Dirty, a patented dyestuff derived from textile waste, which the company claims is one of the most sustainable dye technologies currently available on the market.

Fade in

Interest in vintage-looking denim and Y2K styling—from both brands and consumers—is behind the resurgence of dirty washes. The grungy effect is brand new to Gen Z consumers who’ve unearthed wide, boot cut, flare fits and more in their post-pandemic quest to ditch skinny jeans.

However, full-on dirty tints are still an extreme in the mainstream market, said Bill Curtin, BPD Washhouse owner. He said the look is “still a few seasons away” from being a full-blown trend.

“Certain customers who have a younger consumer target or more grunge aesthetic to their range have requested development around these dirty and trashed looks,” said Melissa Clement, Isko head of product development.

Tonello added that the effect has always been in fashion from the 2000s onward. “It has never been the star but has always maintained its slice in the collections of many brands,” she said. “Even today it is still used with more or less intensity—sometimes even without being so clearly discernible.”

The wash underscores consumers’ unwavering fascination with nostalgic fashion. Venier said “recreating the worn and yellowed parts that characterize a naturally used garment” is “really on trend now.”

“But today, the interest is also in being able to achieve this kind of bleached, distressed and worn look, while impacting as little as possible,” he said. “Our task is precisely to meet this need.”