I Survived a Murder Attempt. Here’s What It Taught Me

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

You’d think I would never forget the night I was almost murdered. But I did.

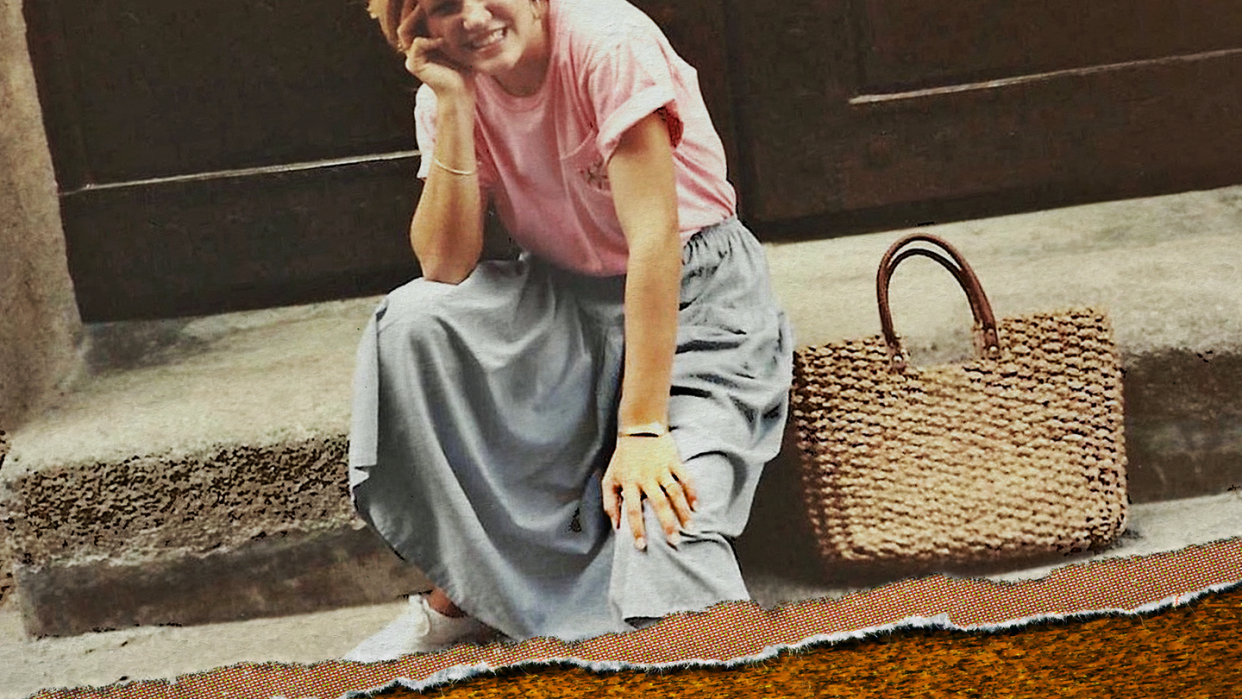

In the summer of 1989, I attended a study-abroad program through the University of Houston and met a fellow student named Kelly Robinson. She and I hadn’t known each other before, but we became good friends during that semester. We moved in together with a family and took six credit hours at the Colegio Mayor Chaminade in Madrid. We mastered the Metro system, attended a bullfight, took a day trip to Segovia, went out with classmates. She had an infectious laugh and a really great smile. I have photos to prove it, otherwise I wouldn’t be sure. After returning to Houston, I forgot all about Kelly. I forgot her last name, where we’d lived, what we’d studied. No, that’s not entirely right; I didn’t forget all about Kelly. I remembered the pervasive sense of gratitude I felt toward her. I finally got to tell her why after I searched for and found her 34 years later.

I was 19 when I arrived in Spain. Right before I’d left Houston, my longtime first boyfriend, John, and I had broken up. My heartache felt the way opioid addicts describe withdrawals: like I was made of broken glass and the only way to feel better was to get more of what had shattered me in the first place. I was desperate—desperate, I’m telling you—to talk to him, so much that it was, apparently, all I talked about. Telefónica de España’s public pay phones were broken for some reason during that pre-cellphone summer, and international calls were too expensive to make from our host family’s line. One night toward the end of our trip, Kelly and I went with some other students to a terraza, forming a circle with our chairs, drinking beer. As the evening went on, friends of friends joined us, and the circle grew larger. As I was bemoaning my lost love, a man I didn’t know leaned over and said to me, “I couldn’t help overhearing you. I know where you can make a phone call.” He was smiling. I hadn’t noticed him sit down.

“Really?” I asked.

“Yeah, sure,” he said. “It’s only a couple minutes’ walk from here.”

I was so overwhelmed with relief and excitement at the prospect of talking to John that I didn’t even stop to think about the fact that this man was a complete stranger. He looked all right. Clean-cut, friendly, plain. “Oh, thank you,” I said, standing.

Kelly grabbed my hand. “Are you really going with him?”

“It’s fine. I’ll be right back,” I said, giving her hand a squeeze.

I followed Michael—he introduced himself as we threaded through the other chairs—out to the street, and we began walking. He was a few paces ahead; I was floating behind, lost in preparation for the call I was about to make. Then he stopped at the driver’s side of a car parked on the street and unlocked it.

“Get in,” he said.

Wait. I stood on the sidewalk. “I thought you said it was close. Why do we need to drive?”

“I underestimated.” He didn’t coax. He just shrugged and stood patiently with his door open, waiting. I remembered that it was I who was putting him out, not the other way around. “If you want to go, get in. It’ll be faster this way.” He sounded tired.

Did I want to go? Yes. That’s all I wanted. Of course I would go. I got in, sank into the too-deep leather seat.

“Good girl,” he said. Good girl? Had I just obeyed him? As he pushed a button to lock the doors, he looked intently at me. He was sweating and his eyes were dilated, and right then I knew: I’d made a terrible, terrible mistake.

He squealed out of the parking space and began a high-speed race out of downtown Madrid, dodging cars and running lights. It was strangely quiet inside the car; he didn’t honk or turn on the stereo or speak. I could hear my heart banging inside my head.

“Where are we going?” I asked him. My instinct told me to keep my voice calm. He answered by jamming down on the accelerator, which shot my body backward into the seat, pinned my head against the headrest. It was too dark, and we were going too fast for me to read any of the unfamiliar street signs. Soon, we were on a freeway, traveling at speeds above 160 kph (100 mph), weaving in and out of traffic, which I remember being heavy, even that late at night.

“Please stop,” I said, but it was like talking to someone lost in a video game. His eyes were narrowed on the road, his arms locked out against the steering column. What can I do? What can I do? If I screamed or grabbed the wheel, he might lose control. At that speed, I couldn’t open the door and jump out. I wanted to end this nightmare, but I also didn’t want to die.

I tried to sound like a stern parent: “Michael, you have to stop the car.” He laughed at that and slammed on the brakes. In the middle of a multi-lane freeway, he came to a dead stop. I could smell rubber burning. Cars dodged us, horns blaring. I tried the door, but my shaking hands couldn’t figure out how to unlock it. What was I going to do, anyway—run out into oncoming traffic? He laughed again, tossing his head back. He’s on coke, I thought. I couldn’t believe the words that came out of my mouth next: “Just drive.”

He sped up again, and we continued until he exited the freeway and pulled into an abandoned-looking warehouse district. There was graffiti on metal shutters, trash cans, broken lights above entryways. No people, no cars. None. He pulled in front of one of the buildings and killed the ignition.

“What are we doing here?” I finally whispered.

“You wanted to make a phone call, didn’t you? Well, now you’re going to make your fucking phone call.”

I looked out the window, hoping I’d just imagined the danger. Hoping that we were actually just going into a place of business, that there really was a phone I could use. When I turned to him to say I didn’t need to make a call, it wasn’t that important, he flashed a switchblade in my face, then pressed the flat side against my throat. There was hate in his eyes. He licked his lips and said, “Here’s what’s going to happen. I’m going to slit your neck and then fuck you in it. And when I’m good and done, I’m going to leave you here to die. Nobody will find you. And nobody will find me.”

I had a thought as clear as a command: I am not going to die like this. I can’t remember now what I did first, in what order I slapped or punched or pinched or kicked. I don’t know where my blows landed on his body. There was no sound except for the occasional grunt—his or mine, I can’t tell you. I have no idea how long it lasted. Seconds were equivalent to hours. Somehow, I peeled the knife away from my throat, I know that, because he fumbled for it on the floor. I know I hit him in the face, because it was suddenly bleeding. Or I was. I hooked his nostril and slit it with my fingernail, scratched him across the cheek. I hit him again and again, and his wild pummeling in return finally slowed down enough for me to fumble behind me for the lock release. I kicked and flailed my free arm until the door opened, and then I spilled out onto the concrete. I ran behind the car, uphill, in the direction from which we’d come, glancing over my shoulder every few seconds. He was moving slowly, but he was coming. He held the knife aloft; I saw it glint in whatever light there was.

Where not a single other sign of life had been, a pair of headlights appeared ahead of me, and I ran toward them, waving my arms. The car, a powder-blue sedan, stopped, and I rushed to the passenger window, begging the elderly couple to let me inside. “That man”—I pointed at Michael, who was closing distance—“is trying to kill me.” The old man unlocked the door, and I dove onto the backseat. I didn’t want to see how close Michael had come to the car; I already knew how close I’d come to dying.

We drove back to the city. It may have taken an hour or more, or maybe less, I don’t know. I don’t remember any of us speaking aloud at all for that long drive, but somehow, we made it back to El Centro. I didn’t know the name of the terraza, but after we drove around a while, I recognized the restaurant. “There’s my friend,” I said. Kelly was there, waiting for me outside. Everyone else had left by then, but she was still there. The old man drove his car right up onto the sidewalk so that I could get out without having to touch the street.

“Oh God,” Kelly said, opening her arms to me as I stumbled out of the car. “What happened?” I fell against her, and because I finally could, I cried.

The old couple must’ve left. I didn’t even thank them, and I never saw them again. I can’t even conjure their faces.

Kelly wanted to go to the police station, but I refused. I didn’t know the make and model of Michael’s car. He’d told me his first name but not his last. In spite of our proximity, I couldn’t recall a single identifying feature. The image of him faded immediately until he was nothing but a man-shaped shadow. Except for the blood on my hands, the skin under my nails, my torn shirt and bruises and aches, the experience dissolved the way a nightmare does upon waking. The emotions were there, but the story disassembled into improbable fragments.

Within a few days, I finished my semester in Madrid and flew home. I didn’t tell my family about my ordeal. I spoke of it to no one. It wasn’t that I was ashamed; it was that it seemed too unreal. Like I had left my body for that period of time and reentered only after I was safe. I didn’t feel traumatized or victimized. I had only a detached sensation that I had narrowly escaped something and the awareness that I had, in fact, escaped. I didn’t want that experience to define me; I wanted nothing more than to put the whole mess out of my mind. But here I am, in my mid-50s, and I’m realizing that in fact, it has defined almost everything about me since then.

After college, I took up weight training. But I didn’t just tone up; I became a competitive bodybuilder and fitness athlete. Later, I became a firefighter, the only woman on my crew. I studied various martial arts, eventually earning my fourth-degree black belt in tae kwon do and a certification in Krav Maga–based tactical self-defense. I didn’t deliberately try to become stronger than most men, though it’s easy enough now to see why I would. I wanted to make sure that what happened in Spain would never happen to me again. It hasn’t, and it won’t. I’ve been steadily turning myself into a weapon for the past 30 years. But becoming my own bodyguard wasn’t just about defending my body; I built a powerful outer shell so I could protect the 19-year-old girl deep inside me who wanted to make that stupid phone call. So I can teach other girls how to protect themselves, too.

In May 2021, I decided I was ready to write about that awful night, so I gave it to a character named Paula, the protagonist in my latest novel, The Young of Other Animals. Having someone else experience it allowed me to examine it closely and yet at a safe remove, as if from behind shatterproof glass. It was after I put the details down on paper that I started to wonder if it had really happened the way I remembered. Reading my own account made it sound impossible. Hard to believe I’d actually survived. Sometimes, people who experience traumatic events recall far more trauma than they actually endured, a phenomenon known as “memory amplification.”

Had I misremembered it? Amplified it?

Or had I made it all up?

I didn’t know why I hadn’t kept in touch with Kelly. I’d tried unsuccessfully over the years to find her. I posted her photo on Facebook, reached out to the director of the program at UH, tracked down the one person whose name was written on the backside of a photo from that summer. “No, sorry,” they all said. “I don’t remember.” I had those few photos, at least. Without them, I’d have questioned whether Kelly even existed.

At the suggestion of a clever friend, I pulled up the university yearbooks online and did a search for “Kelly.” And there she was. After a little more sleuthing, I found her employer and reached out. It was a fraught few weeks, waiting for her reply. I’d only said that I was eager to reconnect, not that I wanted to debrief her three decades after a life-altering event to find out if I’d distorted my memory of it. Finally, she wrote to say that she had an idea why I wanted to talk and that she was looking forward to it.

Her voice was kind. Slow and easy. Familiar. We exchanged the highlights of our post-Madrid lives. Then I asked her to tell me what she remembered. To my surprise and delight—yes, delight—her account of that night was nearly identical to mine. She remembered Michael, and being concerned about my going with him, and him showing her his driver’s license (which I don’t remember), and then my account of everything that had happened—the high-speed drive out of the city, the knife, the fight, the escape. It all matched. I hadn’t exaggerated any of it. She said she remembered it so clearly because it was formative. There were lessons she took away from it.

“How you ever found your way back, I have no idea.”

“That old couple drove me.” I told her about the man pulling up onto the sidewalk. I was hoping she could tell me what they looked like, what they might’ve said.

“I don’t remember that,” she said. “You came out of the hedges. I remember you were wearing a white T-shirt, and it was ripped. You were hysterical.”

Hysterical, I recall. Hedges, no. I emerged from a car, not hedges.

Soon after I finished the first draft of The Young of Other Animals, I stopped by a Little Free Library on my street and picked up a worn hardcover copy of Where Angels Walk, by Joan Wester Anderson. It’s a collection of true accounts by people who believe they’ve been rescued by angels—not something I’d normally read. Nonetheless, I was compelled and started it as soon as I got home. “Throughout time,” Anderson writes, “angels have typically appeared in whatever form the visited person was most willing to accept—perhaps a winged version for children, or a benign grandfatherly type for a woman in distress.” My skin goose-pimpled, and I took a photo of the page to share with a friend. A shaft of sunlight illuminated that exact line. I have the photo to prove it.

Was it a miracle? The shaft of light? Or that the old couple, who might’ve been angels in a powder-blue sedan, had rescued me from certain death? Or perhaps it was that I finally found Kelly, who confirmed that I hadn’t experienced memory amplification. Or that I found her and she’s now back in my life. Or perhaps it was the fact that I turned trauma into an opportunity to help other women.

Actually, it’s all miraculous. All of it. I survived. I’m here.

The Young of Other Animals: A Novel

amazon.com

$13.21

Little AIn a powerful conversation with Oprah, Oprah Daily Insiders, and Tyler Perry, we discuss how to grow from trauma, learn to forgive, and understand grief. Become an Oprah Daily Insider now to access this conversation and the full "The Life You Want" Class library.

You Might Also Like