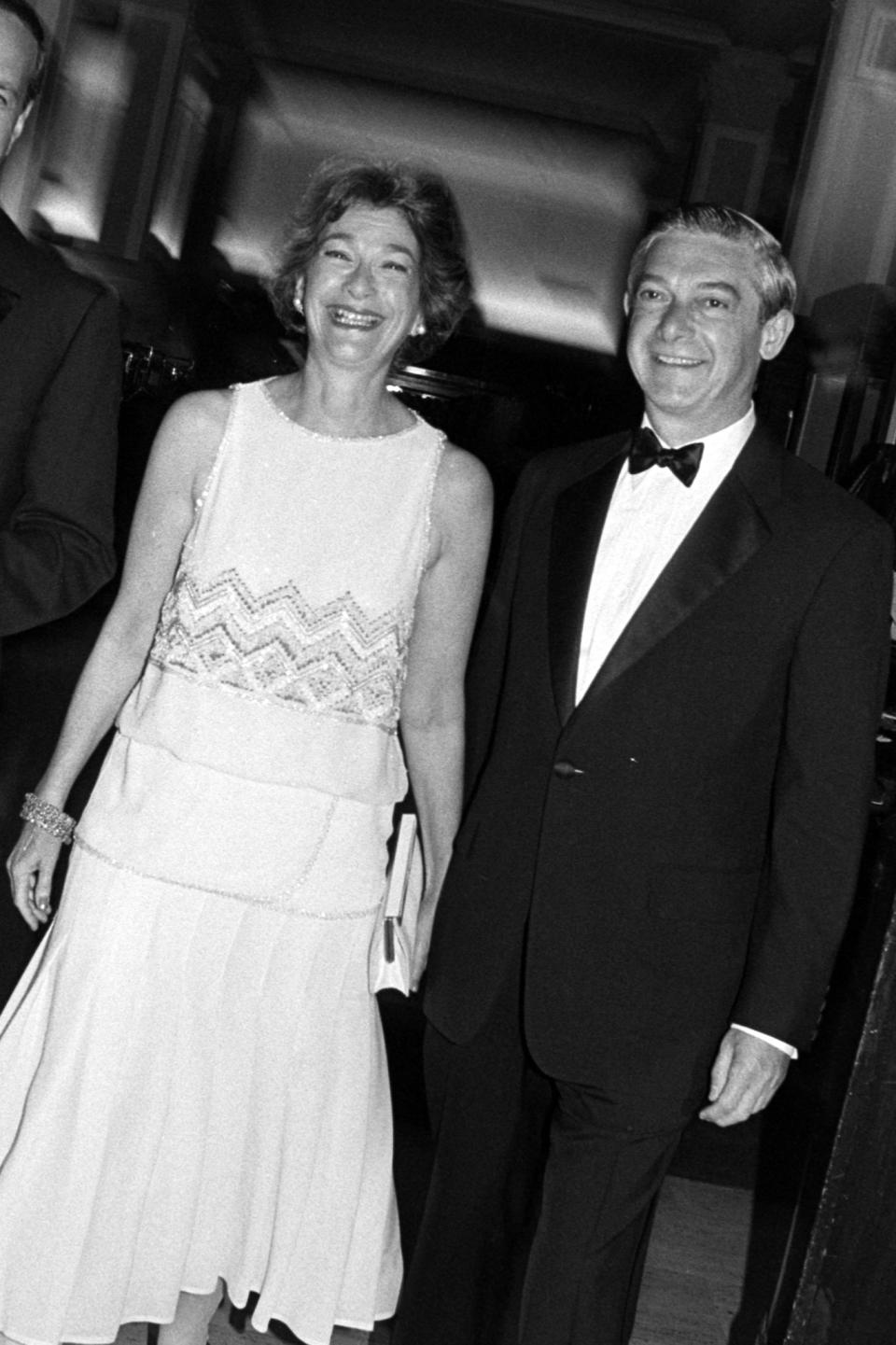

The Surrealist World of Rosalind Gersten Jacobs and Melvin Jacobs

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Could two people have been more connected?

Rosalind Gersten and Melvin Jacobs were young retail buyers at Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s, respectively, when they met randomly at a party. They had a secret romance and eloped six weeks after their first date because, in the ’50s, it was forbidden to marry someone from the competition and Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s were archrivals back then. Then Rosalind brought Melvin into her circle of artist friends.

More from WWD

“Their sensibilities were really aligned in terms of how they saw the world,” said their daughter, Peggy Jacobs Bader.

Roz, as she was known, rose up the ranks of Macy’s, becoming a senior vice president and national fashion director, and Mel, as he was known, rose to co-chairman of the former Federated Department Stores (then Bloomingdale’s owner), and subsequently chairman and chief executive officer of Saks Fifth Avenue. Jacobs ran Saks during one of its headiest periods of growth and managed the business for awhile with a heavily stacked team of prominent executives that included Arthur Martinez, Burt Tansky and Philip Miller.

Tony Palmieri/WWD

“My parents were both self-made. They came from humble beginnings,” said Jacobs Bader during an interview Monday. “They were both creative merchants. My mother’s grandmother was a couture dressmaker working in her town house on the Upper West Side. My father’s family were furriers and his brother ran a shoe store. Retailing was in their blood.”

They also shared a passion for Surrealist art and, over the years, accumulated an extensive collection, which they kept entirely on display at their home, never in storage. Mel passed away in 1993; Roz in 2019.

On Saturday, May 14, Christie’s will present “The Surrealist World of Rosalind Gersten Jacobs & Melvin Jacobs,” a collection of fine art, sculpture, photography and jewelry from European and American artists – 77 lots total – in a live single-owner sale. There is an accompanying online sale of the collection containing fine art, photography, posters and ephemera, with 84 lots.

In total, the sales are expected to realize in excess of $20 million. The highest value lot is Man Ray’s beguiling “Le Violon d’Ingres,” a 1924 photograph of his lover and muse Kiki de Montparnasse. According to Christie’s, it has an estimated value between $5 million and $7 million, the highest of any single photograph in auction history. The artist held onto the original until 1962 when the Jacobs became its custodian.

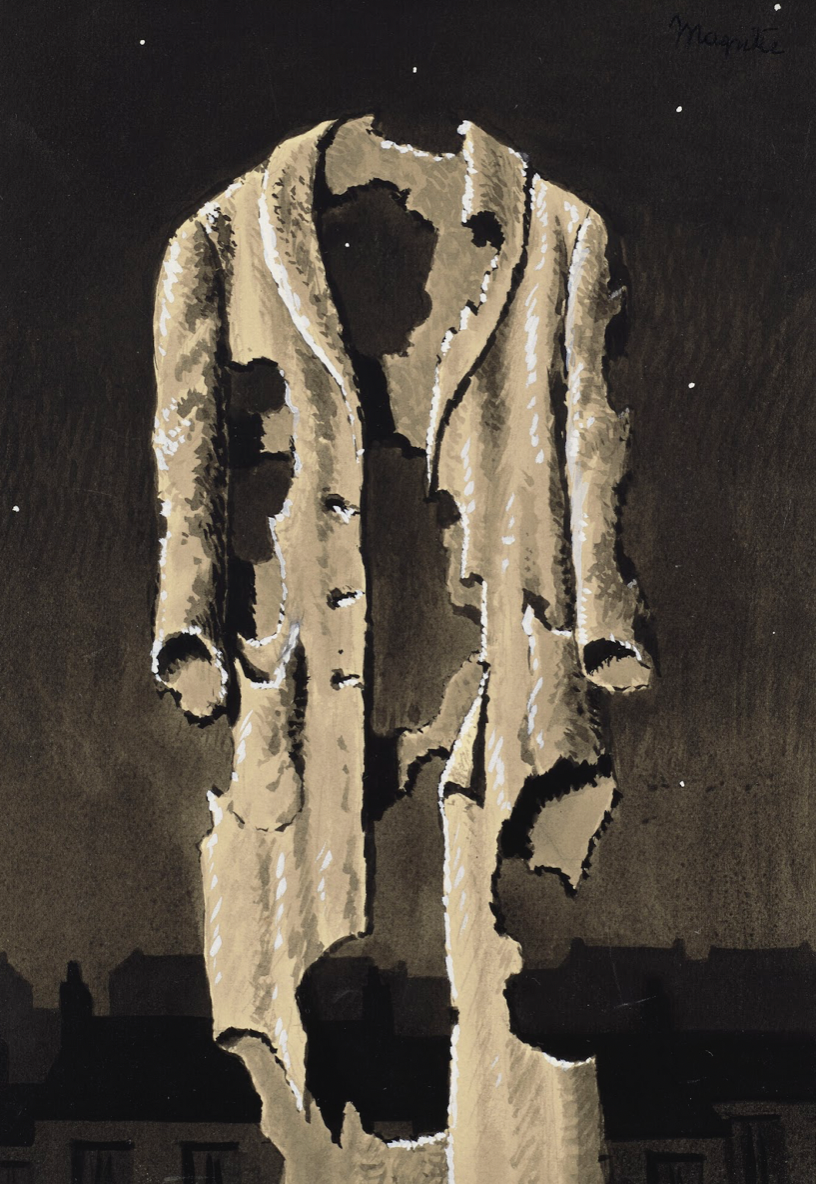

Though the works by Man Ray are at the heart of their collection, the Jacobs also owned six works by René Magritte, including the enigmatic gouache “Eloge de la Dialectique,” valued between $2.5 million and $4.5 million, and the “L’autre son de cloche” oil painting estimated between $4 million and $7 million.

Another of the collection highlights is Vija Celmins’ meticulously rendered “Mars,” estimated at between $1.8 million and $2.5 million, as well as Marcel Duchamps’ “Feuille de vigne femelle,” seen taking in between $500,000 and $800,000.

There’s also “American Girdle,” a mix media painting by gallerist and artist William Copley, depicting red, white and blue girdles that were sold at Bloomingdale’s. When the Daughters of the American Revolution protested them, Bloomingdale’s stopped selling the girdles but before the girdles disappeared, Copley got Jacobs to send him some so he could paint them.

In 1954, Roz attended the opening of a Broadway musical called “The Golden Apple.” The composer, Jerome Moross, was her friend and also a friend of Copley’s and his wife, Noma, an artist as well. They lived in Paris and came to New York for the opening of the show.

When Moross introduced Roz to the Copleys, she mentioned she was about to embark on her first buying trip to Paris, and they said they’d love to see her there. Roz, who was buying for a row of designer shops inside Macy’s called “The Little Shops,” phoned the Copleys upon her arrival in the city, and they invited her for dinner. Among the guests was Man Ray and his wife.

“That’s what started everything,” said Jacobs Bader.

Roz became part of a coterie of artists and art lovers that included Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Marcel Duchamps, Man Ray, as well as the Copleys, who gave Magritte’s “Eloge de la dialectique” to Roz as a birthday gift. It became the beginning of the Jacobs’ collection.

“My mother always used to say, she thought surreally,” said Jacobs Bader. “Surrealism just made sense to her, but a lot of it had to do with humor, the twists of what we consider reality. I had some pretty strange art in my house that all just seemed very normal.”

Roz first met Mel at a party, just as they were both leaving. He asked her if she attended the opera that week, then she asked, “How did you know?” He said he remembered that the woman he was with had admired her coat.

He soon asked Roz out on a date and six weeks later, they eloped. He had proposed at a bullfight in Mexico, when Roz was with the Copleys in Mexico. He was in California visiting his mother and William Copley, who knew of Roz’s romance, flew him to Mexico.

“They kept their marriage a secret until she was spotted by her boss in front of the Plaza Hotel kissing a young man,” said Jacobs Bader. “She had to come clean and tell him it was their honeymoon week.” They worried they would be fired “because they worked for competitors.” That didn’t happen.

“I think they were in the right place at the right time, just the perfect storm of temperaments and sensibility,” as retail merchants with creative bents. “My mother was a painter and studied drawing in college. My father studied the oboe at Juilliard.

“My parents never considered themselves collectors. They never meant to create a collection,” Jacobs Bader added. “They felt very close to the artists they met. The friendships came first, and then they bought many, many pieces from the artists directly. It was like bringing their friends home with them. The collection in many ways was curated by the artists. That’s not how most people buy and live with art. There was no intent to consider what would increase in value one day.”

Even after artists had died, the Jacobs remained extremely supportive, lending art for scholarly reports and for shows. “They always felt it was important the artists in the Surrealist movement be recognized and have their day. But if it wasn’t for Bill and Noma Copley and their mentorship with my parents, there would no collection,” Jacobs Bader said.

Beyond the financial incentives, there are other reasons for the sale.

“My mother is not here anymore. I guess my mother was the final custodian of this group of art. I feel it’s time for these pieces to go out into the world and start a new adventure. I’ve lived with them my whole life. It’s time for them to have a new adventure. I’ll keep a couple of little pieces for myself, and my father’s oboe.”

Sign up for WWD's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.