Supreme Leader: The Extended James Jebbia Interview

GQ: When it came time for Supreme to really start making clothes—my understanding is that this happened when the stores in Japan opened, and you needed more stuff to sell—what were the inspirations? It’s apparent that the clothes were for skaters, and reflected what skaters in New York were wearing, but you took the quality beyond what other skate brands were doing at the time. Were you looking to fashion brands? Helmut Lang and Ralph Lauren come to mind as possible sources of influence.

James Jebbia: I guess the influence was the people who were around the shop—the skaters who were shopping. They would wear cool shit; they wouldn’t wear skate clothes. It would be Polo, it would be a Gucci belt, it would be Champion. But it’d also be another element—not skate but a sensibility of being in New York. They wouldn’t all wear just the typical stuff. It’s the way people would mix it up. And I think that’s really what we try to do, just mix it up. Make what we felt we really liked. And it kind of was a gradual thing. From a few tees, a few sweats, pair of cargo pants, a backpack. But the influence was definitely the young skaters in New York. Also traveling to Japan and seeing their great style. Traveling to London. It was a combination of that. I think one of the things was—I never really, and nobody here ever really looked at it as, “This is what a skate brand must make.” We just tried to make what we thought was the coolest shit we could make.

Was there an awareness of higher-end designers?

Hell, yeah. Of course. We weren’t blind to Helmut Lang. We weren’t blind to FUBU either. There was an awareness of a lot of what was going on out there—being in New York, you’re very aware of that. But also, I don’t feel we chased trends. It wasn’t like, “This is what’s really trendy right now.” It was more like, “This is, for our very limited customer base, what we feel is cool.”

Was there an awareness of the high-low element of it?

No more than it is now. It was more to do with just being aware of—through magazines, people walking around—people’s own personal style. But there wasn’t as many big fashion brands then. There just wasn’t. We were certainly aware of what was going on, but I don’t think we look at something and say, “Oh yeah, we’ve got to do something like Chanel.” But I’ve got to say: Helmut Lang at that time was really important, personally. You’d just see a lot of regular people in Helmut Lang, too.

Helmut’s approach to design was very utilitarian. To a certain extent, Supreme is utilitarian—for skaters who have a stronger eye than just “I don’t give a shit about what I wear.”

Definitely. But it was also never really a plan there to just be like, “Let’s make this line.” We have to make some stuff. Again, in Japan, they mix things up really well, too. So we also had to make what we felt like—what’s that kid in Japan, what’s he going to want? Knowing we’re a New York brand, we didn’t want to be a Japanese brand. We’re not trying to emulate what’s coming from Japan. We’ve got to do our own thing in a very authentic, real way. That’s really what we tried to do. But I’d say the main influence came from the streets of New York, and it was people like A-Ron, Harold [Hunter], Justin [Pierce], just how they’d mix stuff up—they’d wear their stuff in a very particular, real way.

Do you remember what the first cut-and-sew piece you made was?

I actually think it was a pair of cargo pants. Apart from a sweatshirt. It was funny: When we were doing the mural [at the Bowery store], Futura was like, “Remember these?”

He was wearing them? Shit.

Yeah. He said he’d gone through some old shit and found them. It was just a tiger-stripe cargo pant.

How an upstart NYC skate brand changed fashion forever.

One of the most remarkable things about Supreme from a fashion perspective is the consistency of the design and the quality of the production. It’s incredibly rare to see outside of the elite luxury brands like Hermès and Chanel. How have you been able to maintain this consistency when most brands eventually succumb to the fickle fluctuations of the fashion market? Do you feel any kind of kinship with these luxury houses?

Not really. [Laughs] Yes, I could say Polo. I could say at the beginning, too, A.P.C. or Agnès B. They both had their own distinctive look. It wasn’t really “This is what everybody’s doing, so we’re doing that.” It was fairly consistent. So I can definitely say those brands were ones I felt had a consistent, cool look. Even Stüssy. Again, at that time, when we were doing things—apart from Helmut Lang, Chanel—there wasn’t really Louis Vuitton clothes. Gucci wasn’t anything we’d look at like that. Because those brands actually weren’t making clothes then. Or if they were, it was old men’s clothes. Chanel was a whole other big thing. Comme des Garçons… Not that we really looked at them for inspiration, but we were very aware of what luxury brands were doing.

The thing that all those brands have in common is that they were sort of filling a gap, a void that was there in the market, rather than following the trends.

Something that was missing, kind of. And I feel the same today. In some ways, when we opened, if there had been great stuff for us to buy, we wouldn’t have needed to make anything. And wouldn’t have made anything. So that wasn’t a thing, ever, that I thought we were going to make any clothes. And then you see, like, “Okay, that’s actually missing in New York.” And I didn’t think of that for anywhere else. I was just thinking about the people that came into the shop—the people of New York—what they wanted, and there was something missing. And if I look back, it was no different in terms of the shop—there was something missing from skate shops. I was not thinking about it at the time, but it was just an instinct that something was needed. At that time, too, in L.A., X-Large was really cool. They filled a void. I remember when they first opened, they came out, Check Your Head–era, and they started with Ben Davis. And I think for them it was like, “We’ve gotta be doing some of our own stuff.” And I think they did a great job. They were very cool.

On the side of the quality of the product, in the early days, was there a steep learning curve?

At first, if we were doing a sweat—and you bought a Lee or a Champion one, that would be of a high quality—we would have to make ours of equally high quality. Even a blank tee at the time—Oneita would make them—were of good quality. So that really started it, that we’ve got to make our pieces of the highest quality to stand up to what was already being made. It’s got to be as good as, if we’re making it, Polo. It’s got to be as good as what the kids in New York want. Because that’s one of the reasons they didn’t buy a lot of the stuff that we bought [for the store] at first. With a lot of the skate brands at the time, the quality wasn’t good; the fabrics were kind of crappy. So we had to make our product that was as good as the brands that kids in New York were wearing: Polo, Nautica, Carhartt, Levi’s.

But there was a consciousness of what these skaters could afford, too?

Yes, but it’s the same as I feel now. We’re going to make the product as good as we can, and we’re going to try to put it out as reasonably priced as we can. We don’t want a $600 shirt. We want a shirt which is around $100. For us, the reason that our quality has been high, and I feel that our pricing has been reasonable, is because we don’t wholesale. But our thing was to try and make things as good as the best brands out there—but not the fashion brands—and have that quality that people are going to wear these items for a long, long time.

Well, they have to, because skaters wear the shit out of everything.

Regular people do, too. I think that when we started, at the time, people didn’t spend as much money on clothes. And I don’t think they needed to have, like, ten different jackets. Now, I think people buy a lot more clothing than they used to.

What’s the in-house design mandate for a new collection? It’s apparent that much of the collection references vintage sportswear designs from the ’80s and ’90s. How much of that is intentional as part of the Supreme design ethos? Or is that more of an incidental result based on making the standard, classic pieces that are in a sense native to the style of Supreme?

I guess a lot of what we do comes from ’90s-era, because that’s when we opened and started. But I also feel that was a golden era for clothes, for music, for art, for a lot of things. So that’s always something that we are influenced by. I think, for us, a lot of the things that we do are based on what happened in the ’90s, but a lot of people were doing very similar things in the ’90s. If you go to Macy’s—Polo, Nautica, Perry Ellis, so many brands—there was a quite similar kind of thing. And here’s the thing, a lot of what we do can come from the ’90s, but can come from different places. We’re still influenced by many things—it can come from anywhere. We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel with what we’re doing. If you look at what we do, a lot of the shapes are very simple. We’re always doing things our own way. I think most of the time, people can tell that’s a Supreme piece.

42 Pieces from Inside Supreme's Own Archive

A Rare Look at the Supreme Fashion Archive

It always struck me that the meticulousness of the store—the tightly folded T-shirts, etc.—was more about presenting the product in an elevated way, not just a reason to be rude to customers. And since you don’t wholesale, you can really control the experience of shopping for Supreme. The products feel designed and manufactured with similar meticulousness. Has this always been part of your vision? How do you think you’ve developed this kind of sensibility? Or do you have major influences, inspirations, that have led you to think this way?

I think the reason that we do things the way we do is because we respect the customer. And I don’t look at what we do as anything less than any other brand. I still feel like we’re a skate brand—it doesn’t mean we can’t present our stuff well. It doesn’t mean that when you come in, everything has to be messy. I know that’s what people think, but for us, it was more like, “How can we present things well, and treat it with the same respect?” You go into Staples, and the Post-its are displayed nicely. You go into Barneys, and things are displayed nicely. Why shouldn’t we display things as nice as we can? Some of the things that we do in the shop—we have no choice, actually, with the way we display things. With the clothing, too, we don’t dumb it down for people. I’ve always looked at it as: Why shouldn’t we make good stuff? Why shouldn’t we try to present it in a good way? Why shouldn’t we use a great photographer? That’s just really the mindset. Most people, at that time, were used to skate brands being presented a certain way and then looking at us—well, that’s not what a skate brand’s meant to do. Your thing is meant to be kind of scruffy. You’re not meant to care. Our thing still has to have a natural edge to it, so it’s not like we’re trying to soften anything. Why shouldn’t that tee be really good? Why shouldn’t those jeans be really good? Why shouldn’t the shop itself look good? I think a lot of that came from the influence of Japan. Because when you go to Japan, they did things in a great way. Nigo was doing incredible things with A Bathing Ape. He was elevating things. He was doing a Gore-Tex jacket, he was using the very best zippers. We were of the same mindset in our own ways. It wasn’t overthinking, it’s just how we approached things.

On that note, you said that brands like A Bathing Ape, Neighborhood forced you to elevate the Supreme product. But I think Supreme is just as much a part of the fashion lineage that includes other designers we’ve discussed: Helmut Lang, Ralph Lauren, and to some extent, more avant-garde labels like Comme des Garçons and Undercover. In a way, it’s the least surprising thing in the world that a skate brand would be elevated to that status. Skateboarding is an exercise in precision, style, and physical presentation. Are you at all concerned with the position of the brand’s legacy? It is, in a sense, a total anomaly. Do you feel like you have to decide if Supreme is a fashion brand, or a skate brand, or something else entirely?

I don’t think we have to choose that. I think that we’ve just evolved. We’re trying to make things for young people. And we’re trying to make it the best that we can. The way people dress, what they listen to in music, it evolves. For us, we try and evolve. Twenty years ago, if we’d have put a fur coat out at the shop—the skaters would have stormed out. Our windows would have been smashed. In 2013, young people, skaters, they’re more open-minded. They’re a lot more open-minded today. We take that into consideration. That same thought is there. We’re trying to make things for today’s youth. We’re not stuck in a box; we’ve just evolved in our own way. And sometimes we’re the people who are actually pushing things. We’re not sitting back saying, “This brand just did this, let’s…” Most of what we do comes from a real place, but it evolves—the way people dress and what they’re comfortable with. We don’t tend to take the easy route.

Do you feel like Supreme helped make skaters more open-minded about style?

Definitely. But you see certain skaters—young Mark [Gonzales] is a big influence, the way he dressed. Sean Pablo, too. There are skaters who are really individual and who really take chances. Throughout the history of skating, you’ve seen people who have crazy style. No different than the Beastie Boys. There’s always someone in skating, a few people, who are like, “Fuck this, I’m wearing this.” And it’s like, “Oh, shit.” This is a whole other thing, but I also feel like Pharrell had a big influence on that, too. A lot of people used to think that if you’re into hip-hop, you’ve got to dress a certain way. I’ll always remember Pharrell at the MTV Music Awards, he just had camo cargo shorts and a tee on, and a trucker hat. He showed that you can still be yourself when everyone else is doing things one way in hip-hop. He was an influence, too.

In the breaking down of labels, identities.

Yes, whatever you’re into, you don’t just have to dress that way. There’s many ways you can feel comfortable dressing. That’s how I feel. You don’t have to be stuck in a box, whatever you’re into. That’s how it is now: If you like something, you should feel comfortable wearing it.

"If we could have done a thing with Louis Vuitton 25 years ago, we would have."

Supreme got the attention of the fashion world early on. There was the Vogue article comparing the shop and a Chanel boutique back in 1995. A few of the recent collaborations have leaned into fashion in a pretty direct way: Vuitton, Gaultier, Comme des Garçons, and before them, Thom Browne, A.P.C., Adam Kimmel. But do you find the brand is becoming more receptive to, or more interactive with, the fashion world? In other words: Are some of these moves you wouldn’t have made 20 years ago, but for some reason feel right today?

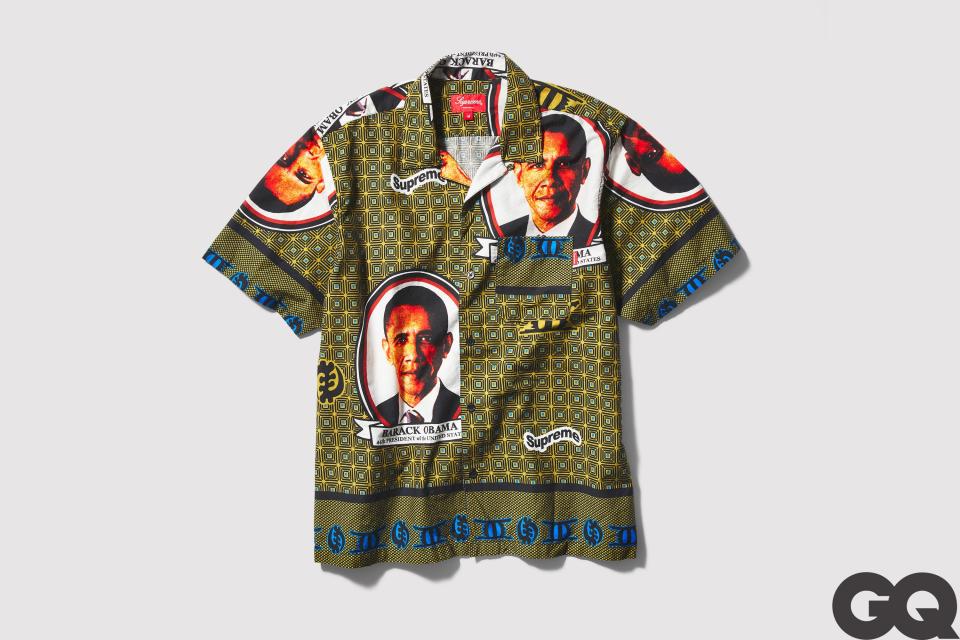

If we could have done a thing with Louis Vuitton 25 years ago, we would have. Or Chanel. For us, whenever we do something, it’s something we feel like, for young people, this isn’t already a part of their world. Or it isn’t accessible to them. We could do something that opens people’s minds to something they hadn’t known or thought about before. Like when we worked with Lou Reed. That was just cool. You may not be checking for that, but it’s something that’s very cool. We would have done certain things back then, but now—we’ve done things from Louis Vuitton, but still work with Anti Hero or Thrasher. Because what’s good is good. That’s really the criteria. And if it’s been done, we don’t do it. Simple as that. If other people have done it, or we’re not at the forefront of things, we just don’t do it. Or if we don’t feel like it’s something that’s necessary and exciting for people.

Your model for weekly product drops has totally rattled the fashion world. It’s actually amazing, and sometimes hilarious, to see fashion houses big and small try to replicate this model. It seems to me that the thing most fail to get about this approach is that it only works if people actually want what you make. It’s not an effective way to create desire if there is none. Can you give some insight on your intention for selling the collection this way? Is the collection designed specifically to fit into this model?

Short answer: No. But for us, it wasn’t any kind of strategic planning. It was more out of necessity, when we made things, not having the certainty and means to be able to order an item for the whole season. We’d make some tees, some sweats; if they don’t sell, we’re going to be stuck with them. So we made less quantity because, again, we didn’t know. And if it was really good, it would sell. Then we had nothing left to sell. We couldn’t call up the people and ask them to remake it, nor did we really want to. So it was: “Okay, if that does well, we have to replace it with something.” That’s what we had to do. It wasn’t a shop full of basics where we’d have stuff for two months. I didn’t want that either, where you could get the same product month after month. What we were doing had to have some excitement to it. We never wanted to say, “We’re a company doing basic shit.” We always wanted to do things that we feel people would really get a kick out of, really love. So with that, you’re trying to make things that are potentially pushing things a little bit. Apart from the obvious pieces, we didn’t know what was going to be successful. Back then there was no press, no Instagram, none of that. It was a few people being like, “I think that looks good.” We’d order it, and we’d order small quantities, out of not having certainty or funds to deal with it if we were left with a ton of stuff that people don’t like. It was never intentional. We’d actually have some seasons where—there’s our summer stuff, and we were sold out of the product at the end of March. We have nothing to sell in April, May, June, July. People would come in and be like, “This shop is shit. Why are people talking about this?” And what are we gonna say? “If you’d have come in two weeks ago, it looked really good?” There’s nothing in there. So it was more about that.

Over time, subcultures become mainstream, and my sense is that it can be devastating for brands that rely on authenticity to sell stuff. But this phenomenon doesn’t seem to have negatively impacted Supreme. What kind of calculations have you made to protect yourself from the ups and downs of popularity and success?

We can’t do anything but try and put out what we think is the best things possible. After that, it’s on the customer to decide whether they like it. I feel that’s what we try and do. If people’s taste and style change radically, I’m not really sure. That would mean that we’re not evolving. I feel like, for us, we can just do what we’ve always done, which is try and be open, try and be very aware of what’s going on, and try to make the best things possible for today’s generation while keeping it true to ourselves. If we couldn’t do that, it’d be tough. And I don’t have a crystal ball. But I think that we’d have to stay the course if we’re not as hot. We’d do exactly the same stuff. We’re in the business where that can happen—it is what it is. Many brands have been through that; some come out of it, some don’t. We’d remain who we are; we wouldn’t change.

Twenty-five years in, what are you most proud of?

I’m most proud that we’re still going. I’m proud that I’ve worked with a lot of people for a long time. I’ve got people that I’ve worked with from day one. That makes me feel proud. I’ve been able to support myself, and a lot of the people that work with me. And my kids. That means a lot.

Originally Appeared on GQ