From Sun Kings to Drag Queens: Inside The Met’s Camp Extravaganza

Andrew Bolton, Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, has framed his spring exhibition, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” around Susan Sontag’s seminal 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’ ” Sontag’s essay brought the subject—which she defined as the “love of the unnatural . . . style at the expense of content”—into the cultural mainstream, where, after the Stonewall riots of 1969, it flourished.

The exhibition—which runs from May 9 through September 8—is designed by the theater scenographer Jan Versweyveld, partner of the innovative director Ivo van Hove, with whom he has collaborated on such resolutely un-camp productions as Network, David Bowie’s Lazarus, and the Tony Award–winning A View from the Bridge. The clothes showcased in the exhibition—by designers running the gamut from Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga to Franco Moschino, Bob Mackie, Jeremy Scott, and Donatella Versace—are evidently camp enough to stand alone.

Sontag found camp in Busby Berkeley movies and in the he-man actor Victor Mature, in Mae West and General Charles de Gaulle, in Garbo and Swan Lake, Flash Gordon comics and Caravaggio, chinoiserie and the entirety of the Art Nouveau movement.

“Camp taste has an affinity for certain arts rather than others,” she noted, with fashion in the former category. She cited “women’s clothes of the 1920s (feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses etc.)” and “a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers.” Women’s Wear Daily took up the gauntlet in 1965, citing Yves Saint Laurent’s “Baba” wedding dress as an example, and a year later The Village Voice’s Vivian Gornick dubbed Rudi Gernreich’s topless bathing suit “an especially delicious example of a camper’s delight.” (If you need a visual snapshot of camp in 2019, however, look no further than Cardi B’s red-carpet posturings at the Grammy Awards, dressed in a 1995 pink-satin-and-black-velvet shell dress from the archives of the übercamp designer Thierry Mugler— seen in this story on model Edie Campbell.)

To structure the exhibition, Bolton has explored the elements that Sontag identifies as camp—with artifice, excess, extravagance, irony, nostalgia, démodé, innocence, and surplus among them—as they manifest themselves in fashion. Think of the irony of Virgil Abloh’s little black dress printed with the legend “little black dress” in quotation marks, for instance, or the voluminous dimensions of young British designer Molly Goddard’s net ruffles—or her compatriot Richard Quinn’s collages of 1950s floral prints. Bolton also finds a camp quality in examples of “failed seriousness,” including the work of the intensely serious couturiers Charles James and Balenciaga, including the latter’s 1966 evening gown for the decorative-arts connoisseur Jayne Wrightsman, a dress bristling with individually applied ostrich- feather tendrils. “You end up seeing camp everywhere!” Bolton jokes, citing the sophisticated pop-cultural and historical references of Saint Laurent, Marc Jacobs, and Karl Lagerfeld.

Although Sontag ventured that camp was “something of a private code, a badge of identity,” she did not dwell on its very specifically queer origins. The first written usage appears to have been in a letter dated 1869, sent by Frederick Park, a cross-dresser known as Fanny, to his lover Lord Arthur Clinton. “My campish undertakings are not at present meeting with the success they deserve,” Park notes. “Whatever I do seems to get me into hot water.” “Fanny” and his partner in cross-dressing, Ernest Boulton (known as Stella), were indeed sent to the courts for gross indecency but were ultimately cleared of wrongdoing, to the delight of the crowds. Their story inspired Erdem Moralioglu so much that he based his spring 2019 collection on them.

Aristocratic seventeenth- and eighteenth-century France, too, obsessed as it was with aesthetics and surface, saw a flowering of camp, and Bolton traces the word itself back to the French verb se camper, meaning “to stand firm,” as one does when striking an exaggerated pose—something exemplified by the swaggering portrait of Louis XIV in his magnificent coronation robes, painted in 1701 by Hyacinthe Rigaud. (Although the portrait was commissioned for the Sun King’s grandson Philip V of Spain, the vain king couldn’t bear to part with it and hung it at Versailles, from which it travels to set the tone for this exhibition.)

The Sun King consolidated his power by compelling the French nobility to abandon their country strongholds and gather at Versailles, where the elaborate protocol and demands of dress forced them to squander vast sums to literally keep up appearances. At Versailles, everything was pose and performance: Louis XIV’s effeminate brother Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, was deliberately raised in such a way that he would never prove a threat to his brother’s rule (as many testosterone-charged siblings had in France’s belligerent history), and was in many ways the paradigm of camp. Monsieur, as he was formally known, was obsessed with clothing and jewelry and far less interested in his second wife, the German-born Princess Elizabeth Charlotte, Madame Palatine (known as Liselotte), than in his male favorites. “You’re welcome to nibble his peas,” his wife, evidently fairly camp herself, told them, “for I don’t care for them myself.”

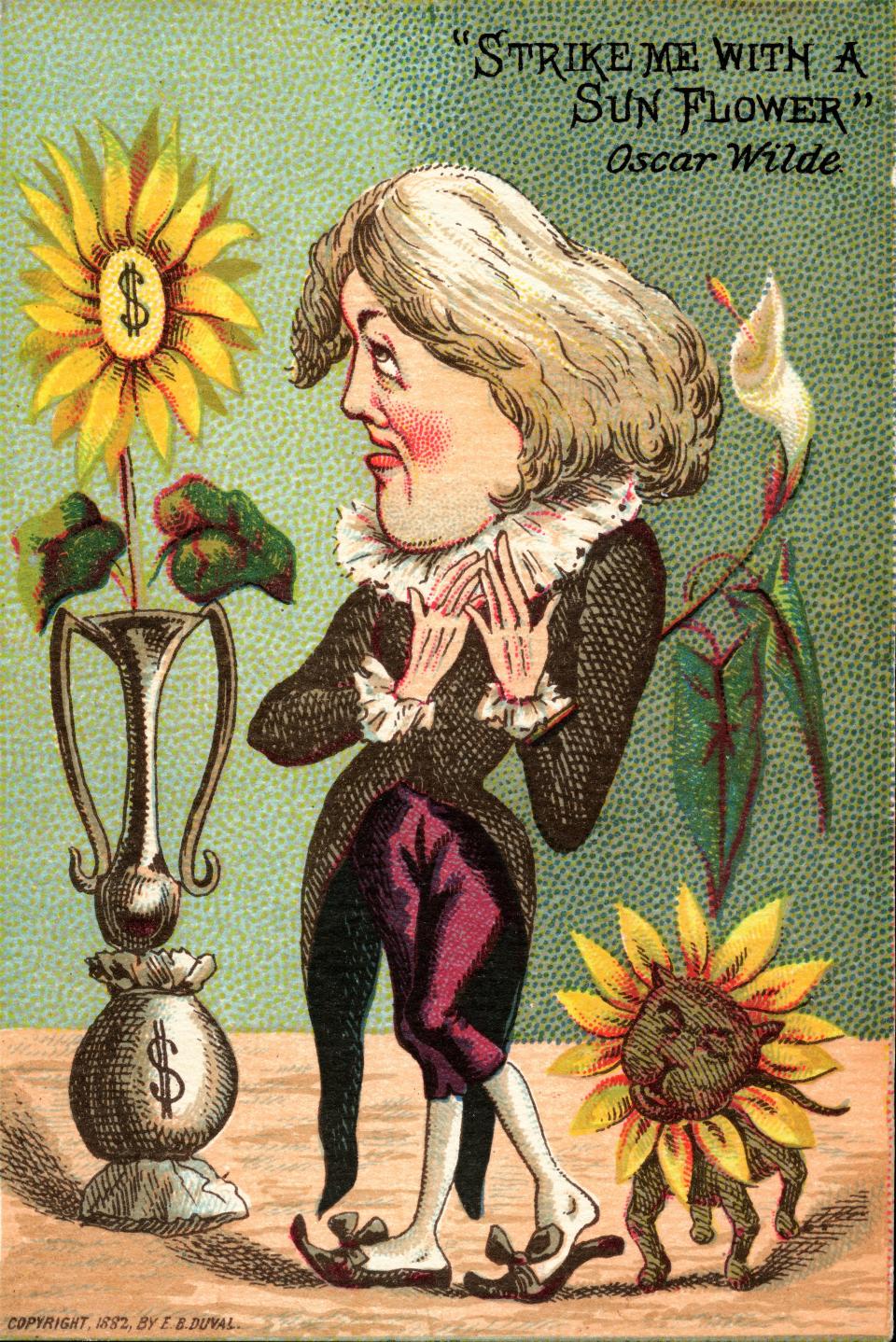

Andy Warhol, with his joyous embrace of high and low culture, was the prime exemplar of camp in the late twentieth century, just as Oscar Wilde had been a century earlier. (Warhol even co-opted Sontag’s essays for his 1965 movie Camp and screen-tested the writer for it.) Wilde’s epigrams—“One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art”—are the essence of camp, but after his terrible fall from grace these attitudes were forced underground. A 1909 book of Victorian slang explicitly describes camp as “actions and gestures of exaggerated emphasis used chiefly by persons of exceptional want of character.” The word gained currency in the early–twentieth century worlds of fashion and the marginalized queer world at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offense, and subtle signals and a coded language developed as discreet signifiers of queerness—along with such sartorial details as the green carnation in a buttonhole that Wilde bade his friends wear to the opening night of Lady Windermere’s Fan in 1892 to mimic one of the actors in the play.

The exhibition, which will be presented in The Met Fifth Avenue’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall, is made possible by Gucci. The cochairs for the Met gala on Monday, May 6, are Lady Gaga, Harry Styles, Serena Williams, Anna Wintour, and Gucci’s creative director, Alessandro Michele.

“I grew up like a little camp kid,” says Michele, but it’s difficult to see how anyone raised in late-1970s Italy on a TV diet of pop stars such as Mina, Patty Pravo, Renato Zero, and Raffaella Carrà (“the most camp woman ever,” Michele asserts) could be unmoved by the concept. “I’m still kind of camp,” says Michele. “I adore putting on something strange and exaggerated and worn in the wrong way. I mean, why not? It’s not forbidden.”

Breaking Camp

In this story:

Sittings Editor: Phyllis Posnick.

Hair: Orlando Pita; Makeup: Hannah Murray.

Tailor: Christy Rilling Studio.

Set design: Julia Wagner.

Produced by Olivia Gouveia for Rosco Productions.