Stylist and Author Jason Jules on Why Menswear Rules Were Made to Be Broken

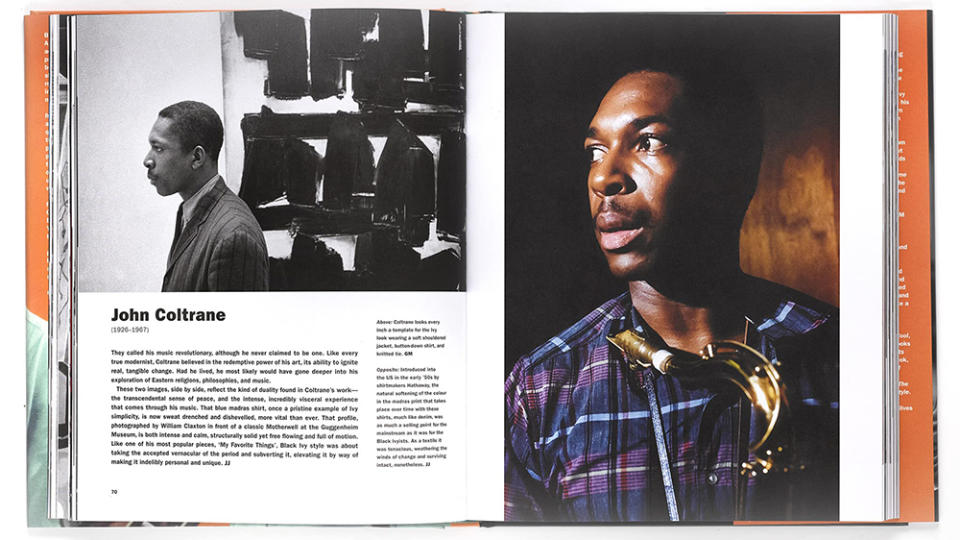

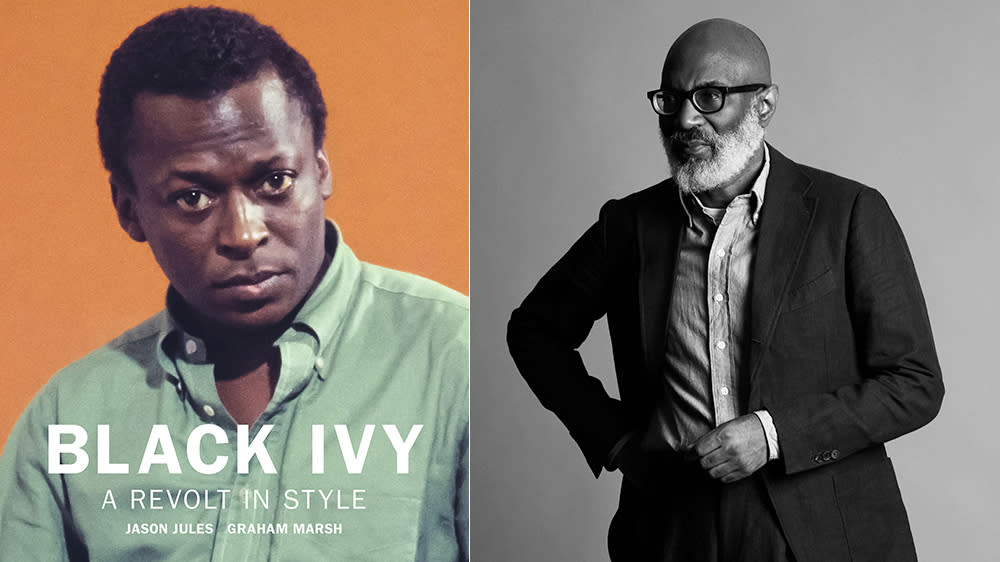

Jason Jules was always going to work with clothes, and it shows. He wears them with an assurance that can only be gained from a lifetime of studying and appreciating them, knowing what came before and what comes next. His former life as a club promoter and publicist gave way to a career as a stylist, designer, model, documentarian, writer and an encyclopedic authority on good clothes and what they represent. This is perhaps most embodied by his recent book Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style, which documents an era in modern history when Black men made Ivy League style their own, challenging societal expectations and looking downright cool while doing so. Full of striking imagery of everyone from Miles Davis to Gordon Parks, it is as much a celebration of style as it is a story of American history.

Jules’s knowledge and passion for style are quickly evident a few pages in, but it’s the way he makes that knowledge accessible that sticks. I meet Jules in the Standard Hotel in London and things are no different. An appropriate soundtrack of jazz music plays overhead as we discuss his career beginnings, style tips and why style rules are overrated.

More from Robb Report

A Copy of Shakespeare's First Folio Just Sold for $2.4 Million at Auction

Sneaker Store Flight Club Reopens in LA, Two Years After Being Vandalized and Looted

Charlie Thomas

Where did your passion for clothes come from?

There’s all sorts of glue that connects a family. Proximity and living in the same house connects you, your genetics connect you, and so on. There’s negative glue of course, in my case perhaps lack of money or my lack of application when it came to education. But the most positive glue in my family was clothing. There was a connection of shared joy when it came to clothing.

I felt a lot of affirmation when my parents were talking about clothes. I used to draw as a kid, and most of the time I’d be really resistant to showing my parents. But one time I drew a shoe, and my dad told me, “That’s really good, you could be a designer.” I must have been about 5 but it really stuck with me. It was a huge compliment from someone who didn’t say anything complimentary ever. It was identity-affirming, in really the most basic of ways.

Did clothes give you more confidence growing up?

Yes and no. I had an idea of what I’d wear in my head and then I’d try to assemble it. Almost 99 percent of the time, the minute I left the front door they’d be a sense of regret. I thought I looked good but most other people thought I was just a bit weird. Clothes did help me develop a sense of self, but almost in a reverse way. It took a lot of experimentation to realize what I was and what I wasn’t.

When going to the West End to go clubbing, I’d kind of know that between leaving my house in east London and getting to the West End there’d be all sorts of negative glances that I’d have to rise above or ignore. But by the time I got there, that would be reversed. I’d be among a group of people who understood me and what I was wearing, which was almost a relief.

Reel Art Press

So you stuck with it?

There was nothing really flamboyant in what I was wearing; it was the opposite. But somehow that grated against people who weren’t part of it. My dad would say, “Why are you dressing like an old man?” My style has always been a very simple, and understated way of dressing. A lot of it was referencing the ’50s and ’60s, but what I also realized as a kid was that I didn’t particularly want to associate with second-generation mods. As a group of people in my school, them and I were opposite ends of the social spectrum.

How did you find your style inspiration in those days?

It was really through TV and books. I watched a series of Fred Astaire films as a kid, which really left an impression on me. I think they connected the dots between what my dad wore and what my mum was making as a seamstress. I remember when I was studying for my A levels I used to go to a reference library. I was trying to study but there was this compendium of old GQ magazines from the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s. They had these beautiful old illustrations and I sort of absorbed them through osmosis. They really gave me a sense that there was some other world, that where I was wasn’t it.

How has the internet changed things today?

I think a lot of people have always dressed the same. People like to fit in. The assumption is that if you’re fitting in you’re doing the right thing—that’s a natural assumption people often have. But I also think that because there’s so much stuff available, what that actually means is that if you want to be distinctive and want to find your own voice, you have to try a bit harder. If you want to not walk out of your house and bump into a replication of you, you really have to figure out some unique sense of style. When I was a kid it was a lot easier.

Charlie Thomas

As a stylist, what are the first five pieces you’d suggest a new client invest in?

It’s hard because the first five pieces would be pieces they don’t have. Most people have a sense of their own style, it’s just a question of knowing how to put it together. My job is really just to give them the permission to go with what they think is right. But also, 90 percent of my wardrobe has had to be altered by a tailor in some way. Most people think you go to a shop and find a jacket that fits right away, but that’s rarely the case. Nobody’s body is exactly the same and it doesn’t matter what size you are, you have to tweak it, alter it or shrink it. You have to make the clothes work for you. If you’re lucky you’ll find something but most of the time there has to be some sort of alteration. Almost before you find the clothes, you’ve got to find the tailor.

Should menswear have rules?

Trends evolve in menswear. So it’s pointless having a set of rules that can’t mold to the trends. But also, rules are meant to be broken. It’s interesting. Jazz was once the music of the people. It’s so universal, most of it is instrumental, there’s no language barrier, and you don’t even have to dance to it. But at some point, it became this intellectual passion, and you kind of had to know about chord changes, you had to understand the history of the blues, you had to understand what circular breathing is and all this stuff. OK, that could all help, but not knowing those things shouldn’t prevent you from being a jazz fan. I think that’s almost the same as clothing. Everybody wears clothes, but just because you’re not so well versed in the terms of tailoring and what this cut is and the warp and weft, it doesn’t mean you can’t look good and can’t enjoy clothes. It’s the same principle.

A lot of the time, the guys that play the best jazz are the guys that are self-taught and the ones who are going against the grain and breaking all the rules. And some of the best-dressed people are the same. So maybe you don’t need to know the rules.

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.