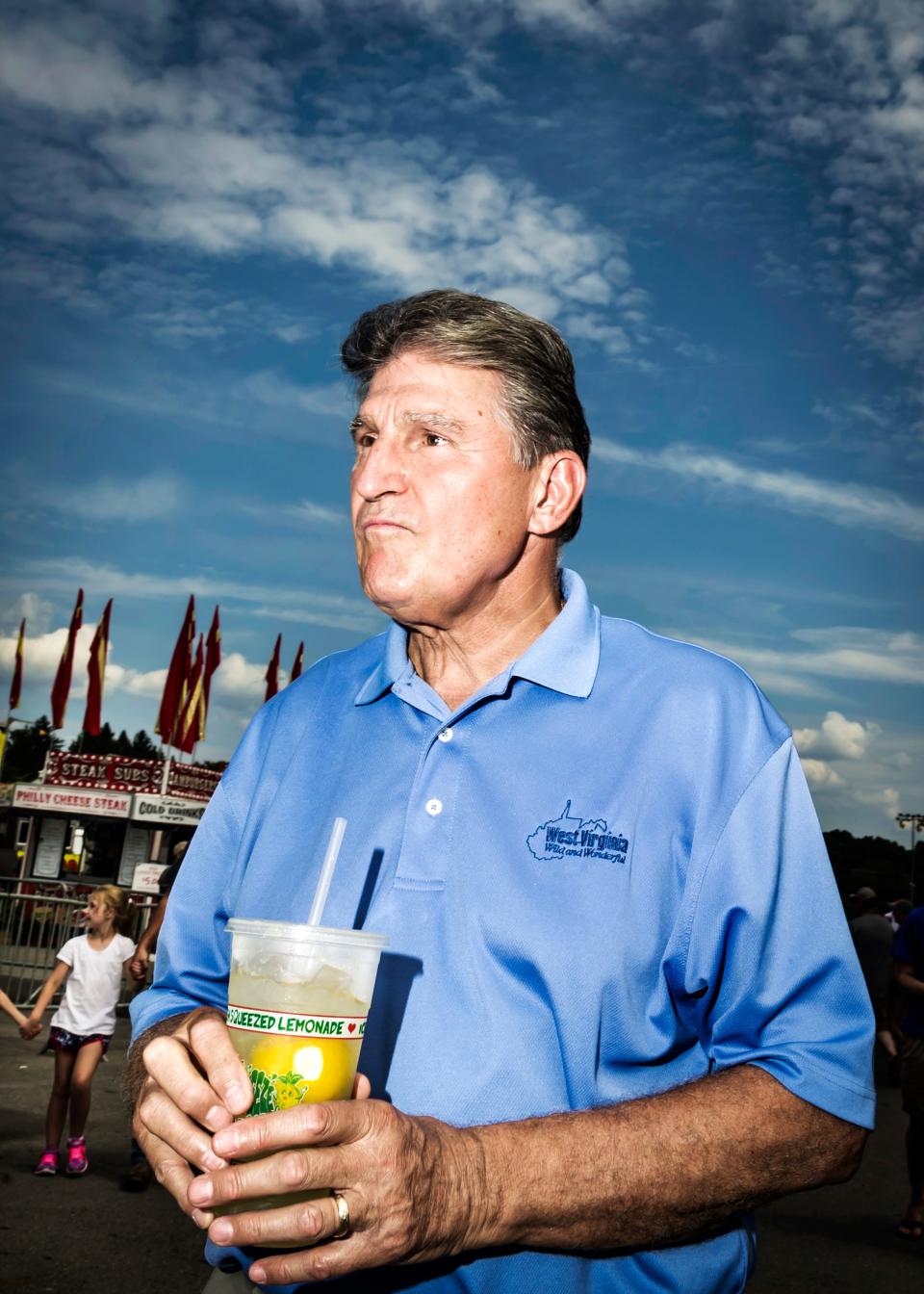

The Struggles of Joe Manchin, the Last Democrat in Trump Country

A summer thunderstorm had opened up on Charleston, West Virginia—coal-black clouds rolling in from the west, flashes of lightning streaking the sky—but Joe Manchin paid the foul weather no mind. In a small office he keeps in the state capital, the Democratic senator leaned back in his chair and contemplated a tempest of an entirely different nature: Donald Trump.

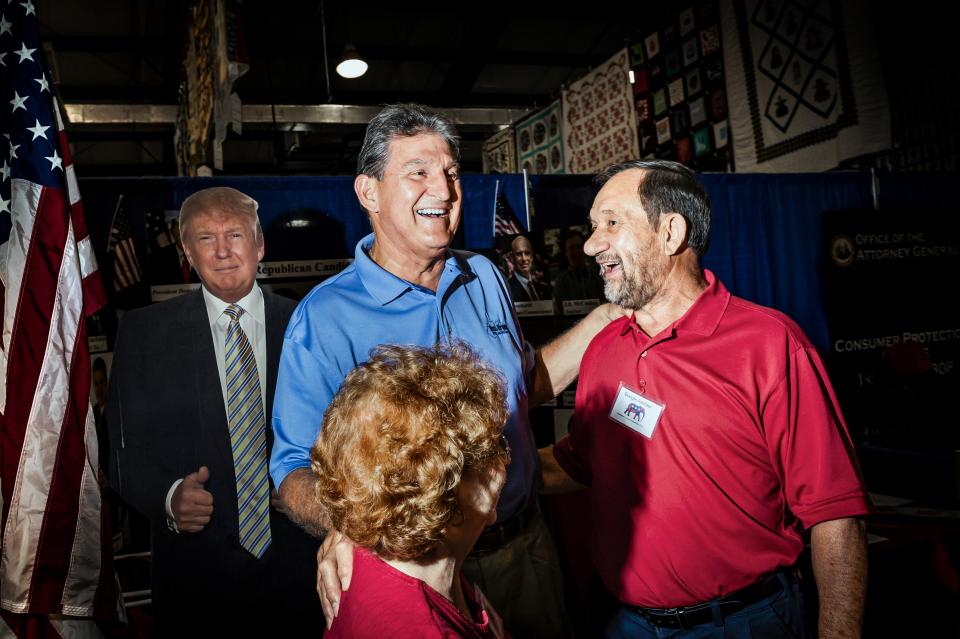

“I mean, we do get along,” Manchin said of the president, almost as much to himself as to me. “We get along. And there's things he's done that I like and support, okay? And there's things I would love to help him with and make him better.” Soon Manchin stopped speaking to me—or himself—and began addressing Trump. “ ‘Mr. President, these Democrats are not all that bad—just because we have a D by our name,’ ” Manchin said. “ ‘It seems like you're the president of the Republicans. I want you to be the president of all of us. You're my president.’ ”

If that sounds to you like an unusual sentiment to hear from a Democrat these days, it's worth noting that there aren't many Democrats quite like the senator from West Virginia. After Trump's shocking victory in 2016, Manchin was perhaps the only member of his party willing to express optimism about what lay ahead. “I don't think Donald Trump is far to the right,” Manchin told me a few days before Trump's inauguration. “I think he's pretty much centrist—a moderate, centrist conservative Democrat.” Manchin marveled about how willing Trump seemed to be to listen to others (in contrast to Barack Obama, who, Manchin told me, “didn't seem like he had any empathy for anyone left behind because of a policy and his desire for social changes he wanted”). “We couldn't get through before,” Manchin said. “You can get through to this guy.”

Eighteen months later, despite all the evidence to the contrary, he stubbornly stands by his assessment. “Every time I've hung around the president, he is always much more comfortable trying to work something in a bipartisan way,” Manchin told me this past summer. “He tries to do the reasonable thing, the responsible thing.” As for why that attitude hasn't been reflected in the White House's legislative priorities or his public rhetoric, Manchin could only speculate and make excuses. “I think the political people around him or whatever have gotten him to believe we don't need to be bipartisan,” he offered.

Trump's tax-reform package, which provided huge, permanent cuts to the wealthy but only modest, temporary ones to the middle class, was a perfect example, he said, of Republicans upending Trump's moderate intentions. “The president told me point blank, he said, ‘Joe, it's not gonna be a tax cut for the rich and the wealthy like me.’ I said, ‘That'd be great.’ His handprint wasn't on that bill. It was all Paul Ryan.” (Manchin voted against the tax-cut bill).

About the only time Manchin expressed any annoyance over Trump was when I asked about the president mocking Manchin for hugging him so much. “He's grabbed me more than I've grabbed him, okay?” Manchin bristled. “Anyway, there's no hugs. You know how guys do the man bump.”

It's hard to know for certain whether Manchin genuinely believes the kind words he has for Trump. It could be that Manchin—bogged down in a fierce campaign to keep his job—just can't afford to get too crosswise with a president whose approval rating is 62 percent in West Virginia, the second-highest of any state, after Wyoming. That's his sister's theory. “I guess my brother Joe has to stay political,” Paula Manchin Llaneza told me, “but, ohhhhhh Lord, it's embarrassing.”

As a political creature, Manchin is a rare breed in these hyper-partisan times. A self-described centrist, he's been a thorn in the side of fellow Democrats since he arrived in Washington, in 2010. During the Obama years, he routinely clashed with the White House and then Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid; under Trump, he's voted with the president more than any other Democrat—backing the White House on everything from Neil Gorsuch's Supreme Court nomination to a bill that would ban abortion after 20 weeks of pregnancy. “I told [Trump], ‘I'm the only thing that keeps you bipartisan,’ ” Manchin says.

But Democrats also know they need Manchin. Though it was once reliably blue, West Virginia is now so solidly crimson that Trump notched his widest margin of victory there, beating Hillary Clinton by some 42 points. The state has become such tricky terrain for Democrats that Manchin nearly didn't run for re-election this year. In January, he had to be persuaded by Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer and a handful of others in the party who staged an intervention. Manchin's odds of keeping his seat weren't great, but without him on the ballot in West Virginia, the Democrats knew they didn't stand a chance.

“People riding a lawn mower—I envy 'em so much. Not a fuckin' worry in the world. Put the earphones on and let 'er rip.”

Manchin's GOP opponent this fall, Patrick Morrisey, has very little going for him, aside from his party affiliation—which, in West Virginia in 2018, might be enough. He's a flesh-and-blood version of the “generic Republican” pollsters are always asking about. Morrisey was born in Brooklyn and raised in New Jersey. After an unsuccessful 2000 congressional run in the Garden State, he moved to Washington, D.C., to work as a health-care lawyer and lobbyist. He later bought a home in Harpers Ferry—the touristy town in West Virginia's eastern panhandle—and began commuting the 90 minutes to Washington.

In 2012, just a few months after being admitted to the West Virginia bar, and with his wife and stepdaughter still living in the D.C. suburbs, he was elected the state's attorney general. What he lacked in local roots and charisma—“He looks like a bowling ball with a bad haircut,” complains one Republican strategist—he more than made up for by having an R next to his name on the ballot. And Republicans are banking that that R—and Trump's support—will be enough to elect Morrisey this November. Polls have given Manchin a slight edge for most of the year, but as Election Day draws near, the race will be one of the most watched Senate battles in the country. As the GOP adviser Liam Donovan puts it: “Manchin's seat is primed for the picking.”

But the race is about something more than whether Manchin stays in the Senate. In a way, it'll test the fundamental nature of our politics—and might just reveal how broken they've become.

For ages, Americans focused their political attention close to home. The only truly national election used to be the presidency. But that's been scrambled. Voters now set their political compass almost entirely on national issues. And as a result, more of our elections—whether for county commission or Congress—now hinge on matters that have little to do with where the votes get cast. As the political scientist Daniel J. Hopkins notes in his new book, The Increasingly United States, our politics have become nationalized.

At the same time, the parties have homogenized: Republicans tend to be just like other Republicans; the same goes for Democrats. This means that today there are fewer places where bargains can be struck between lawmakers, and fewer politicians even inclined to try.

We frequently mourn the passing of the lions of the Senate—giants like Ted Kennedy and John McCain, who reached across the aisle in acts of grandiose legislating. But we overlook the disappearance of another once essential species. We forget the mortals of the Senate, leaders eager to wheel and deal in order to address their parochial concerns. They were the ones, as much as the giants, who made Washington work.

Manchin is a vestige of that old order, someone more interested in doing right by his constituents than in being on a national political team. On Capitol Hill today, that's made him a lonely figure—and an oddly ruminative one.

A few weeks before that stormy afternoon in Charleston, Manchin was in Washington, hustling across the grounds of the Capitol when he stopped abruptly. With his broad shoulders and labored gait, the 71-year-old Manchin resembles a long-retired professional athlete, which he might have been were it not for the knee injury that ended his promising football career as a quarterback at West Virginia University. As we paused suddenly near Constitution Avenue, I worried that maybe his knee was acting up or he'd succumbed to the heat. But no, something had caught the senator's eye. Gazing out into the middle distance, he began to study a Capitol grounds landscaping crew toiling in the afternoon sun, blithely tending to the grass.

“Some days, I just watch,” Manchin told me in a near whisper. “People riding a lawn mower—I envy 'em so much.” There almost seemed to be a catch in his throat. He appeared thrilled by their industriousness, their unimpeded productivity. “Not a fuckin' worry in the world,” he continued. “Put the earphones on and let 'er rip.”

When he was elected to the Senate, in 2010—after a couple of terms as West Virginia's governor—Manchin promised himself that he'd never “go Washington.” It's a point of pride that, from a real estate perspective, he's managed to keep that promise.

When the Senate is in session, Manchin lives on a houseboat that he keeps anchored about eight miles south of the Capitol. He's christened his floating home Almost Heaven—which is how John Denver describes West Virginia in “Country Roads.” He daydreams about the possibilities that living on a boat in Washington present. “I can untie the ropes and away I go,” Manchin says. “I can go right to the front door of where I live in West Virginia.” He concedes that such a trip would be tricky—and it might take him two to three weeks to reach his home on the Kanawha River in Charleston. But what's important, he says, is that he could do it.

That spirit of possibility feels rare in West Virginia. In the public imagination, the state is a backward, beaten-down place—its mountaintops removed in the heedless pursuit of coal, its towns and hollers awash in guns and opioids. That can be more stereotype than reality, but there's no denying the state's problems and pathologies—from its dying coal industry to its nation-leading number of opioid overdoses and deaths. It's a state whose best days often feel behind it.

“It's a tough place to be from, and it's a tough place to make things happen,” says Nick Casey, a former chairman of the West Virginia Democratic Party. “God bless Mississippi, because if it weren't for them, West Virginia would always be at the bottom of everything.”

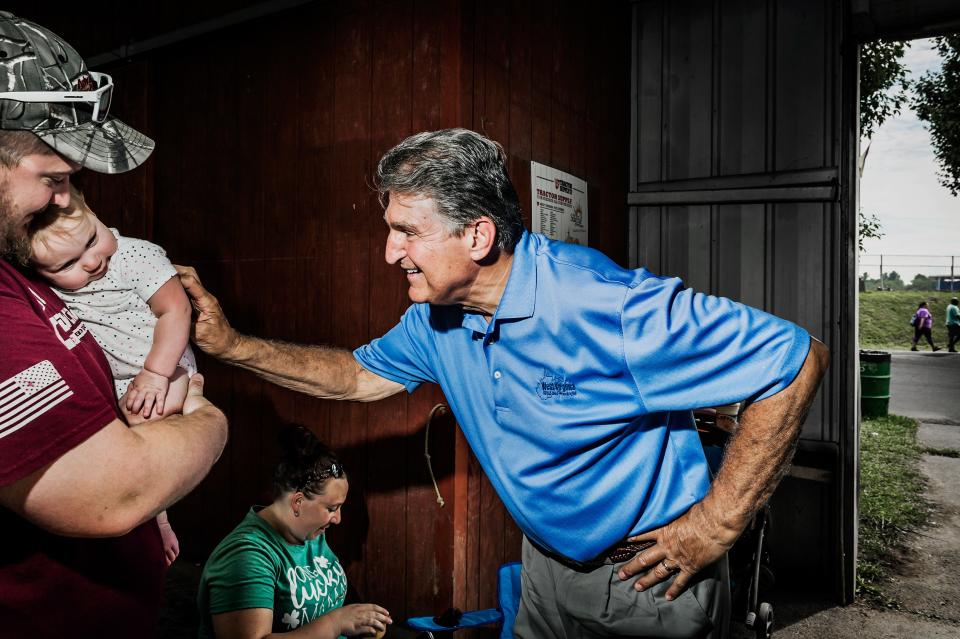

The cultural gulf between Washington and West Virginia is vast, but geographically they're pretty close. As a result, Manchin's Senate office in D.C. features a stream of constituents dropping in, often unannounced, to say hello. Manchin doles out hugs and schmoozes with as many of them as he can, listening to their concerns. “We're retail government,” he explains. “It's customer service.”

The other parts of being a senator, though, can sometimes seem tricky. One day last year, I was with Manchin as he rode the subway car beneath the Capitol to vote on the Senate floor. A few minutes earlier, Barack Obama, in one of his final acts as president, had announced that he was commuting Chelsea Manning's prison sentence for leaking classified information, and one of Manchin's aides broke the news to the senator. Although Manchin serves on the Senate Intelligence Committee, it was clear from the befuddled look on his face that he had no idea who Manning was.

“Bradley—uh, Chelsea—Manning was the Army private that downloaded a bunch of information in Iraq and then gave it to WikiLeaks,” the aide explained.

“That's treason,” Manchin said, still no closer to knowing what his aide was talking about.

“Yes, sir,” another aide went on. “And while he was in prison, he had a sex-change operation.”

Manchin's eyes flashed with recognition.

“I thought that was the one that became a girl!” he shouted. “That son of a bitch!” He slammed his fist on the subway car's seat. “And we're letting him out now because he's docile?!”

The aide tried to explain Obama's rationale for the commutation—that, unlike Edward Snowden, Manning had served time—but Manchin, still hung up on the gender-reassignment angle of things, wasn't listening.

“Jesus,” he fumed. “His mind! He's still got the same mind!”

Even when Manchin's in the right, his lack of understanding can hobble him. One day in May, he was headed to a Senate appropriations subcommittee hearing where Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin would be testifying. On matters of trade, Manchin favors protectionist policies to place tariffs on Chinese goods. He's been frustrated with Mnuchin—“a balls-to-the-wall free trader,” as Manchin calls him—who persuaded Trump to adopt a gentler tack with China.

Barging into the anteroom where Mnuchin was huddling with his advisers before testifying, Manchin walked up to the secretary. Then, leaning toward Mnuchin like Lyndon Johnson threatening a recalcitrant senator, Manchin offered a blunt warning: “I'm gonna hit you on the China stuff today.”

“What are you going to hit on?” a clearly startled Mnuchin replied.

“We're concerned about the changes,” Manchin told him.

“What are you concerned about?” Mnuchin said.

“We're concerned about the technology,” Manchin said, referring to a reported Mnuchin-supported move to lift sanctions on a Chinese telecom firm called ZTE.

“Donald Trump comes to me, everybody comes to me: ‘Oh, just be a Republican, Joe.’ ”

“What-what-what, specifically?” Mnuchin stammered.

“Well, from the things where the president was going, doubling down on the tariffs,” Manchin said, betraying a wobbly handle on his argument.

Sensing his interlocutor was perhaps no expert on the matter, Mnuchin regained his composure. “Did you understand what the deal is before you hit me?” he shot back.

“No, no, no. We're not going to hit you,” Manchin begged off. “We're going to ask you to explain the difference of where the president's coming from and your role in it.”

“I don't understand,” said Mnuchin, now on the offensive. “What's your point?”

Manchin fumbled around, asking about tariff numbers and ZTE. Mnuchin began lecturing him about trade policy toward China. Before long, he was the one questioning Manchin. “Have you been briefed on the security issues on ZTE?” Manchin said he had. “How recently?” Mnuchin practically taunted him. He assured Manchin that there was nothing to worry about from a national-security perspective.

“I think that's the most important thing,” Manchin said meekly.

“Everybody's on the same page,” Mnuchin reassured him.

“Okay, good,” Manchin said. “I hope everything goes well. I'll see you in a little bit.”

The senator left the room and then turned to an aide. “Well,” Manchin said, “he seemed defensive.”

Though the details of certain international issues might bedevil Manchin, the concerns of his constituents consume him. One morning, the receptionist in his office patched through a call from a West Virginian who needed some help.

A station agent for Amtrak, the man had recently been told that his job in Charleston was going to be downgraded to part-time because of declining train ridership. The man wondered: Could the senator do anything? Manchin peppered the station agent with questions, plunging deep into the weeds of the West Virginia rail system. Had track repairs caused delays? How was baggage checked in Huntington as compared with Charleston? Soon he had the facts he needed. “Okay, brother, let me see what I can do,” Manchin said. He hung up the phone and yelled out to his secretary, “Bri, call the Amtrak CEO and say we want to talk to his chief of staff! Or him!”

No small part of Manchin wishes he could spend his days immersed purely in the particulars of West Virginia. He's wistful for the time when that's all he had to focus on. “My worst day as governor,” Manchin says, “was better than my best day as senator.”

In those bygone days, he'd invite legislators over to the red-brick governor's mansion to drink and play bumper pool and to see if they could find common ground. Oftentimes they did. But doing that in Washington seems tougher. For a while, he tried to host bipartisan lunches, but they died off due to lack of attendance. Now he has Democrats and Republicans out to his houseboat. “We have a little bit to eat, a little bit to drink, we talk, sometimes we'll go out for a cruise,” he says. But nothing much ever comes of it.

The odd realities of Washington—a place where effort doesn't often produce results—can be jarring. Especially for a guy like Manchin, who was raised in Farmington, West Virginia, in the '50s and '60s. As a child, Manchin never once left the state, and although he was recruited to play football by colleges across the country, there was never any doubt he'd go to West Virginia University. “He didn't have a choice,” his sister Paula told me. “Daddy wouldn't let [him] leave.” The idea of going farther was anathema. “He's West Virginia,” Paula said. “It's in his soul.” Or, as Manchin told me one day as we sat in his Senate office in Washington, “I want to be in West Virginia. No matter if I'm here, my mind and my heart are always in my state, so I'm always going to think like a West Virginian, and I'm always going to understand what West Virginia is going through and its troubles.”

In recent years, as Manchin has found himself increasingly out of step with his state's partisan makeup—not to mention the national Democratic Party—he's fielded numerous entreaties to jump to the GOP. “They all come to me. Donald Trump comes to me. Everybody comes to me: ‘Oh, just be a Republican, Joe,’ ” Manchin told me.

His Democratic critics often say the same thing. At a political event in Lewisburg, West Virginia, I asked Charkera Ervin, a Democratic activist, what she thought of Manchin. “I actually wrote an e-mail to him, and said, ‘If you get primaried by a Siamese cat, that cat has my full support,’ ” she replied. “I don't know how much progress I'm gonna really get out of him.”

Manchin lamented the decline of “civility and trust” in Washington: “The only way we can change it is to say we’re not going to participate anymore in denigrating each other.”

During the presidential transition, Trump invited Manchin to Trump Tower where, according to sources, the president-elect offered Manchin the job of secretary of energy. Manchin turned it down because Trump would not have allowed him to pick his own staff. Similarly, this year Trump officials felt out Manchin about becoming secretary of veterans affairs, which Manchin also turned down. He wouldn't have been the first West Virginia Democratic elected official to jump ship. Last August, the state's governor, Jim Justice, who was elected as a Democrat, switched to the GOP, announcing the move during a surprise appearance with Trump at a Huntington, West Virginia, rally. Manchin concedes that if he pulled a similar stunt, he'd be easily re-elected. “It'd be a slam dunk in West Virginia,” he told me. “A slam dunk.”

His fealty to the Democrats comes from growing up in what used to be coal country, watching a New Deal ethic sustain the citizens of Farmington, who were mostly all Democrats. “Everybody I knew that worked was a Democrat,” Manchin says. “Everybody that I knew that helped somebody was a Democrat. Everybody that I knew that was a Boy Scout leader was a Democrat. Little League? Democrat. Everything. I never knew a Republican growing up in that little town.” Becoming a Republican would be as alien to Manchin as moving to Pennsylvania.

And yet Manchin tends to be a lot harder on his fellow Democrats than on Republicans—routinely giving the latter the benefit of the doubt over the former. It's this, even more than Manchin's centrism, that infuriates so many members of his party. “He seems to believe that Republicans are on the up-and-up and if he simply sits down and tries to reach a compromise with Senator McConnell, he can get something done,” fumes Jim Manley, a former adviser to Harry Reid and Ted Kennedy. “It's ridiculous.”

But for now, all Manchin can do is keep extending his hand. In February, he went to the Senate floor to lament the decline of “civility and trust” in Washington. More than anything, he blamed it on hyper-partisan politics, on Republican senators trying to defeat their Democratic colleagues and vice versa, and the “hostile work environment” that creates.

Manchin had an idea—and a challenge—that he thought might help. He asked his colleagues to pledge not to campaign for or give money to the opponent of a sitting senator. “The only way we can change it is to say we're not going to participate anymore in denigrating each other and attacking each other,” he said.

It was, of course, convenient timing, just months away from his own showdown on the ballot against Patrick Morrisey—the outcome of which will serve as a referendum on just how nationalized our politics have become. Manchin has made health care a centerpiece of his campaign, attacking Morrisey for a lawsuit he filed, as attorney general, to allow insurance companies to deny coverage for people with preexisting conditions. But even more than health care, Manchin has sought to make an issue out of Morrisey’s West Virginia roots, or lack thereof—all but calling his opponent a carpetbagger. “I welcome anybody to the state of West Virginia,” he told me, “but I think people have to ask, ‘Pat, why did you come? What job did you take when you got here? Did you come for a career change? Did you come because of family connections? What was the purpose of coming?’ ” I asked Manchin what he thought the answer was. “Well, it had to be for political opportunities,” he said.

But it's no longer clear if the carpetbagger charge has much resonance anymore in West Virginia. “Morrisey is running the same playbook they've run against Joe in his last two Senate elections, trying to tie him to the national [Democratic] party, and it hasn't worked,” says Michael Plante, a West Virginia Democratic strategist and former Manchin campaign consultant. “The big question is: Now, in the age of Trump, does it work this time?”

In the meantime, Manchin tries to do what he can to change Washington. One afternoon recently, he decided to propose an amendment that he hoped might protect West Virginia V.A. facilities from closure. It didn't stand a chance of passing, but he thought it could be useful nonetheless to send a signal. “Everything's just posturing,” he explained.

Manchin was in his office, practicing his speech to introduce the amendment, when he noticed a voice mail on his cell phone. It was from Johnny Isakson, a Republican senator from Georgia. As the Republican in charge of the Senate Veterans' Affairs Committee, it would be Isakson who would shoot down the amendment, but he had a favor to ask of Manchin. Isakson, who had been diagnosed with Parkinson's disease a few years back, was feeling especially tired that afternoon. He was calling to ask Manchin if he would withdraw the amendment so Isakson wouldn't have to go from his office to the Senate floor to object to it.

Manchin immediately called Isakson. “I'll do whatever you need me to do, buddy,” Manchin told Isakson. “You don't have to come over.” Manchin explained that he would hunt down a Republican senator to shoot down his amendment so Isakson wouldn't have to trouble himself with it. “You stay right in your office, do your stuff, and I'll make sure someone's there to object.”

Hanging up, Manchin turned to an aide. “Poor Johnny,” he said. “I mean, his health—I'm not gonna have him running back and forth.”

A couple of minutes later, he got North Carolina senator Thom Tillis on the phone. “Hey, Tom, can you do me a favor and Johnny Isakson a favor?” Manchin asked. He explained the situation and why Tillis might want to be the guy to kill Manchin's amendment. “I just don't want you to be too enthusiastic when you do it,” he said. When Manchin got off the phone, he let out a satisfied sigh.

He turned to me. “Lemme tell ya, that's what they don't do anymore,” he said. “That's the kind of stuff, Johnny…” His voice trailed off.

About 15 minutes later, Manchin would appear on the Senate floor to offer his amendment and Tillis would be there to object so the ailing Isakson could sit it out. Manchin's brand of collegiality carried the day. And five weeks later, Johnny Isakson's PAC donated $5,000 to Patrick Morrisey's Senate campaign to unseat Joe Manchin.

Jason Zengerle is GQ's political correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the October 2018 issue with the title "The Last Holdout in Trump Country."